Inside a Courtney Love-inspired art exhibition in New York

Liza Jo Eilers looks to the glory days of Hole at an exhibition at Grimm New York

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

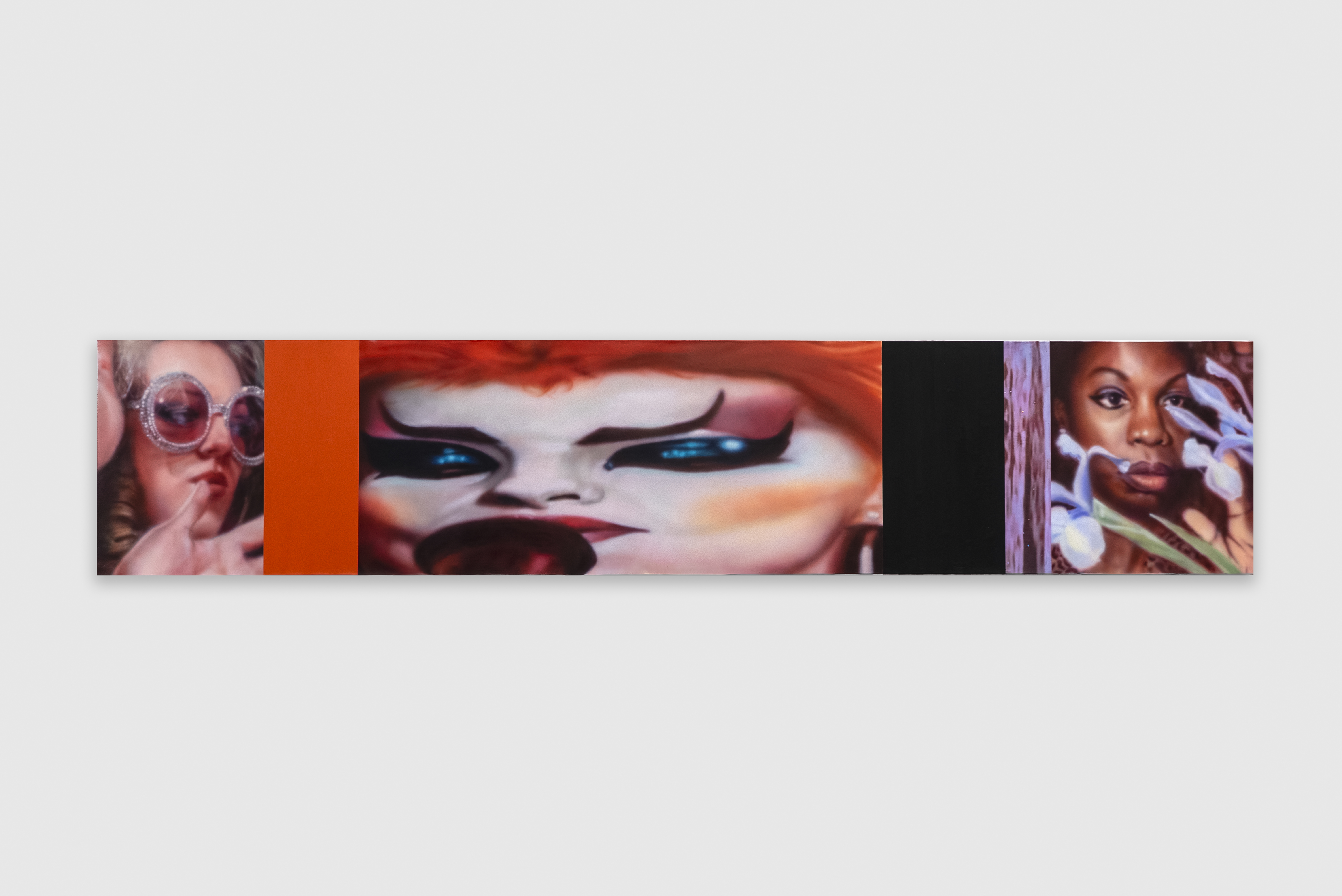

In Liza Jo Eilers’ The trickle down effect (mint), scenes from a Hole concert are spliced together, communicating the relationship between Courtney Love and the band’s fans, depicted by Eilers with their arms outstretched, ready to receive the frontwoman. ‘She’s kind of a controversial figure, but Courtney Love really has a point of view, and I admire that about her,’ shares the artist on a video call. ‘She's also from this politically active era of music, when being political was an embodied thing – versus a post on Instagram; it was worked into the songs.’ The band’s 1994 track Asking for It was conceived in this vein, intended to raise issues about bodily autonomy and women’s safety, directly informed by a stagediving incident Love experienced a few years earlier. ‘I'm interested in this kind of grey area,’ Eilers adds, ‘navigating what is considered okay, what is not considered okay.’

The painting forms part of a new solo show, ‘Starland Silver Sash’, which is currently on display at Grimm in New York; marking Eilers’ first solo appearance in the city, it runs through 1st November. Other significant figures who appear include giants Nina Simone and Gena Rowlands, their likenesses similarly applied to split screen paintings, a device that, beyond aesthetic appeal, connects them to a wider conversation and Eilers’ interest in pop culture’s double bind: how representations of women, on screen and elsewhere, can both resist and reinforce the ideals it supposedly challenges.

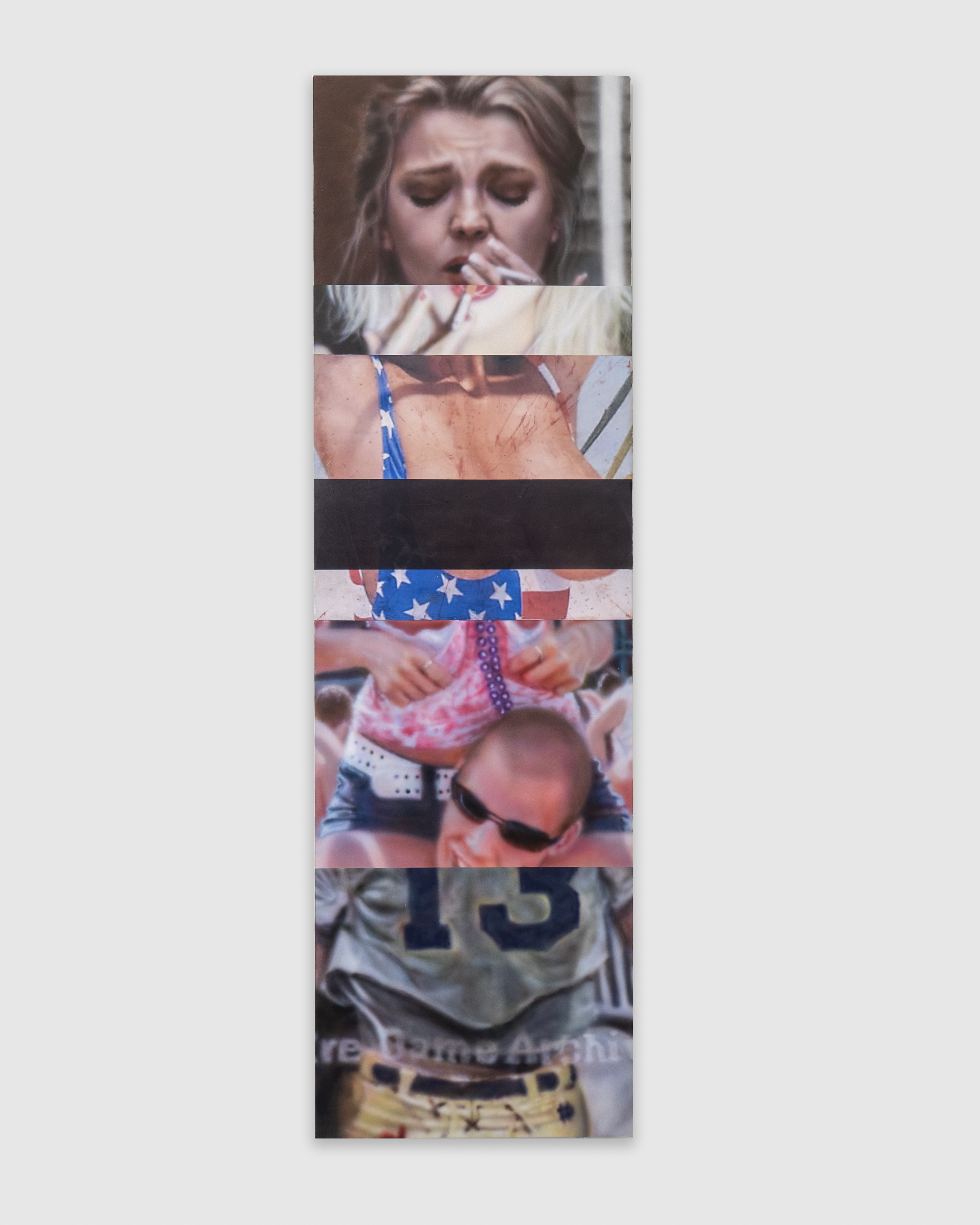

Liza Jo Eilers, True men, like you men, 2025

‘I'm always interested in what’s around me,’ the artist offers. ‘I grew up in the Midwest, and dive bar culture is everywhere. So it’s what you find on the walls – these trophies; the fish men have caught, hot women, the Hot Rod car, things they’re proud to hang on the wall. I've always found it interesting, how a woman is the same as the car, the fish, these objects.’ At a solo show in London in 2024, ‘The Great American Songbook’, she presented Men are just people who write songs about us, marrying this curiosity regarding gender with her preoccupation for celebrity portraits: the work showed an Elvis character covering his eyes with a bra, a particular trophy of the stage. ‘It’s hard, because sometimes it’s freeing, like “hell yeah throw your bra off,” but at the same time, it ends up with that visual of [men] carrying bras around. So it’s dealing with that macho-ness.’

‘It’s very complicated being a woman,’ Eilers continues, ‘and it's very complicated navigating how you're perceived in your sexuality. Courtney Love, for example, finds this amazing way to manipulate this idea of sexuality that is really hard to do, and makes you think “wait, that's not about her”. I do think being a woman is performative, just in the way society is – and expensive, if you buy into societal beauty standards. Maybe that’s why I'm drawn to cinema and music, because it’s a literal performance; I can relate.'

Liza Jo Eilers, A way a lone a last a loved a long the, 2025

Currently based in Chicago, an earlier stint working in high end fashion consulting in New York initially introduced Eilers to the possibility of a visual arts role. ‘I realised you could be an artist. It sounds silly, but there's just such a vibrant art community [in New York], it's much more encompassing in a way that I never viewed it [before],’ she says. She got her MFA in Painting and Drawing from School of the Art Institute Chicago, graduating amidst Covid-imposed lockdowns, a stretch which enabled her to able to explore the perimeters of her practice, becoming, as she describes, a self-taught airbrush artist. ‘I like it as a tool because it is kind of like makeup, but it also talks to the way we view images,’ observes Eilers. ‘I think that's why people respond to it, we're already familiar with this pixilation, so it's kind of like looking at a photograph.’ Using bands of hydrochromic and thermochromic inks, wherein new parts of the paintings reveal themselves at different times (via water or heat), creates a further dimension to several pieces.

‘I work with questions, and I don't really expect answers,’ continues Eilers, relaying her approach to the work. With ‘Starland silver sash’, a moniker borrowed from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (‘He was talking about the Milky Way, but I also like how it plays with movie star, superstar…’), the artist examines “the mechanics of a good time”, interrogating what is, who is and for whom this otherwise straightforward phrase applies. ‘I think it can apply to a lot of things, like bar culture for example,’ she says. ‘Who’s the bar really made for? It’s male centric, you know, like how women used to get in for free because that brought the men in. So who's a good time for? Sometimes it's for us, maybe sometimes it's not for us, sometimes we think it's for us. You can apply it to almost anything.’

Liza Jo Eilers’ Starland Silver Sash is at Grimm New York until November 1

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

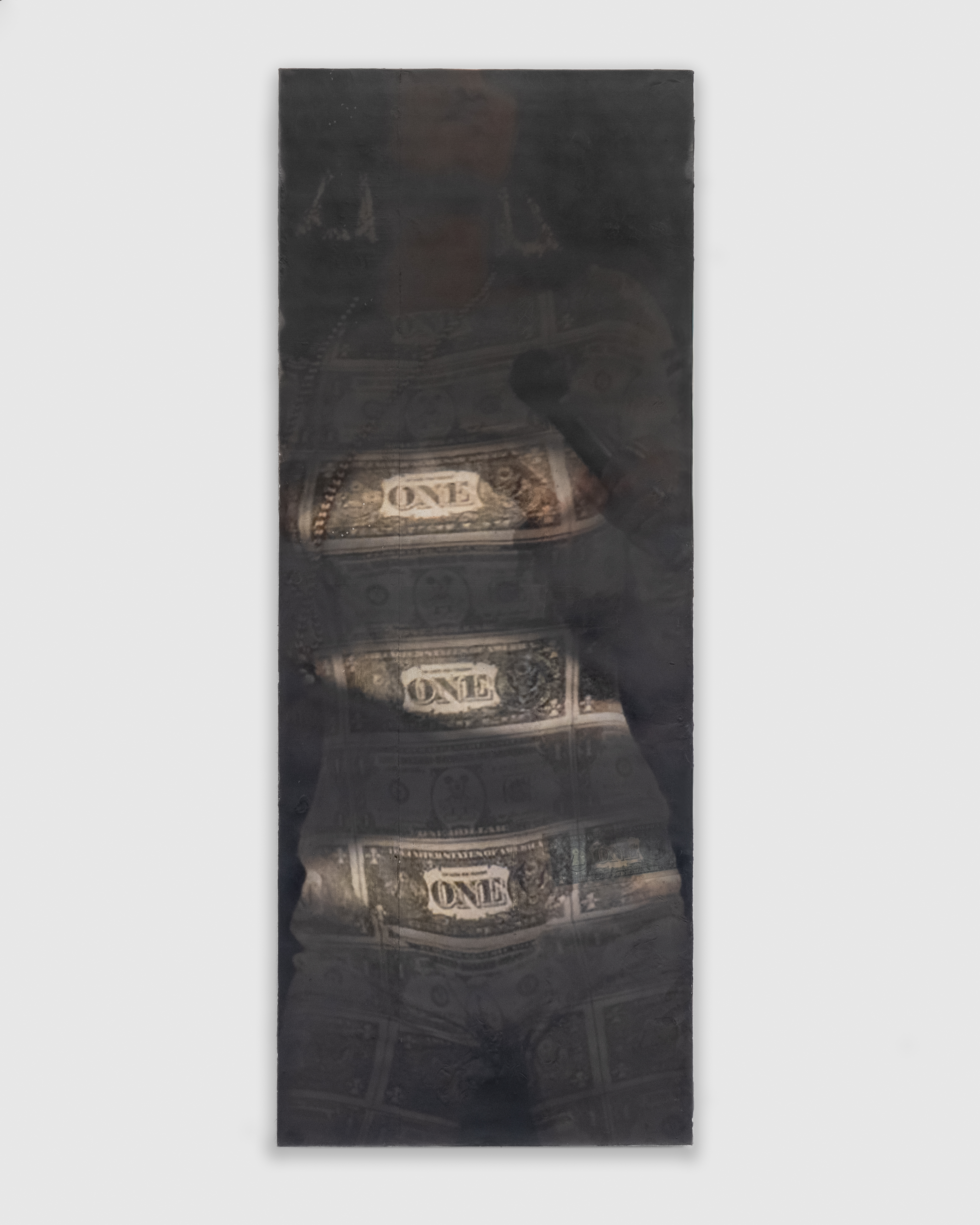

Liza Jo Eilers, Heyy, it’s me, I mean, you know that, 2025

Zoe Whitfield is a London-based writer whose work spans contemporary culture, fashion, art and photography. She has written extensively for international titles including Interview, AnOther, i-D, Dazed and CNN Style, among others.