Houston's Ismaili Centre is the most dazzling new building in America. Here's a look inside

London-based architect Farshid Moussavi designed a new building open to all – and in the process, has created a gleaming new monument

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

When Aga Khan IV, Karim al-Husseini, died in February, he left behind a legacy that centred around faith, charity, his beloved Thoroughbred horses and a passion for architecture. He established the Aga Khan Architecture Award in 1977 to honour exemplary architecture around the world.

Aga Khan IV also served as a direct patron of buildings in his support of a network of Ismaili Centres, worship and cultural spaces for Nizari Ismailis, the branch of Shia Islam he headed (his son, Aga Khan V, now holds that role). The first Ismaili Centre opened in London in 1985. In the 40 years since, five more were built around the globe in locales ranging from Lisbon to Toronto.

This December, a seventh Ismaili Centre will open in Houston, Texas. Designed by London-based architect Farshid Moussavi, the new building continues the Aga Khan's legacy of exceptional design. The focus of the centres has always been outward-looking, containing spaces designed not merely for the Ismaili community but for everyone. In Houston, Moussavi set to build upon that mandate by creating 'an open destination for social encounter.' She's created a dazzling monument in the process.

The Houston centre was commissioned by Aga Khan IV to contain an assortment of spaces: a prayer hall, a theatre, classrooms, a library, a cafe and more, most of which are very specifically open to the general public. Moussavi wanted to work ‘with space, light, geometry, and ornament that one finds in historical works found in the Muslim world, but make them contemporary and make them unique to Houston,’ she tells Wallpaper*.

The site, on Houston’s Buffalo Bayou about two miles to the west of the city’s downtown, lies partially in a 200-year floodplain which meant the building needed to be sited carefully. The resulting five-storey, 150,000 sq ft building is roughly square in plan with one corner removed so that the building, from afar, registers as a series of cubes. It contains three wings, with entrances on each side. 'Instead of having a front and a back, it is all front,' Moussavi says.

The architect and her team incorporated Persianate eivans – or verandas – beneath three entrances, offering outdoor space shielded from sun or rain. These entrances are a gesture of openness but are also useful, enabling easy access to concurrent functions at the same time, with the prayer hall in the main volume, a cafe and social halls to the east, and a library, theatre, classrooms, and more in its western portion.

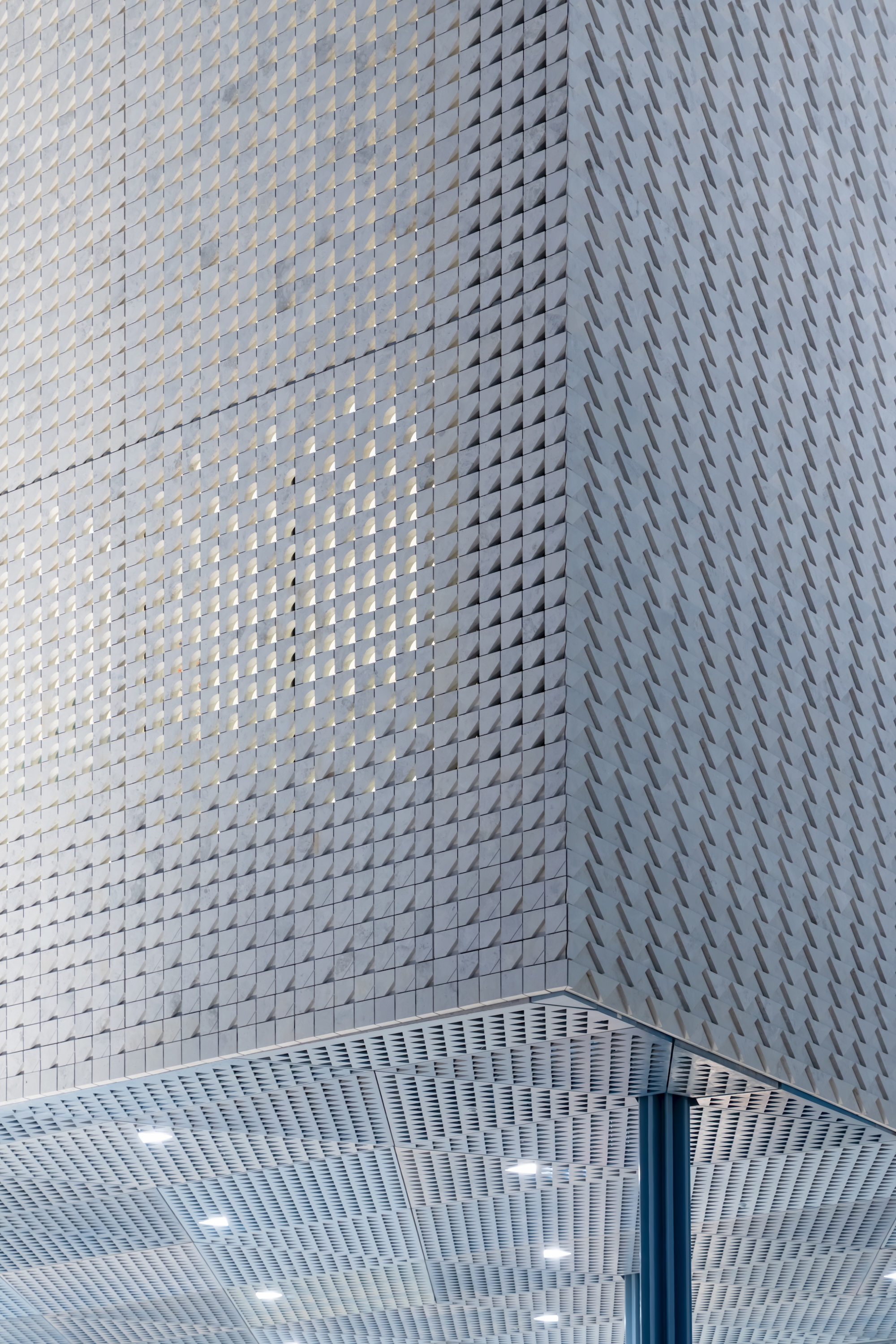

The building is large, but Moussavi leveraged architectural detailing to bring it down to human scale. Portions of the exterior, for instance, are covered in an ethereal screen of triangular and scallop-shaped tiles that are threaded on tension rods. From inside, the effect provides varying degrees of visibility and shade, while casting a dappled daylight throughout the spaces.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Once inside, a central oculus is a moment of great drama. In a move reminiscent of Louis Kahn’s not-quite-barrel-vault ceilings at the Kimbell Art Museum a few hours away in Fort Worth, it isn’t a dome, although it might look like one. 'It is a very contemporary structural system, a Vierendeel system that hangs one floor from another,' Moussavi explains. The move allows for the floors to create a rhythmic, interlocking pattern that culminates in a central skylight.

Looking up is encouraged in more subtle ways, as with a monumental, concrete stair, poured into diagonally-placed formwork that sweeps the eye skywards. 'We are not emphasising gravity but movement. It makes the stair feel light,' the architect says.

Light-touch strategies like this lend a sense of ornamentation, but one that's never overtly decorative. Triangular patterns are everywhere, from the off-the-shelf acoustic plaster ceiling tiles to the pattern on the poured-concrete floors. 'Structure, surface and ornament come together, rather than one overriding the other,' she says – a balance she's achieved startlingly well.

The prayer hall sits underneath the main upper eivan and requires deep beams to span the 115-foot space. It features two layers of patterned aluminium incorporating lighting above. 'As a result, you don't quite know where the ceiling ends, which we hope creates this idea of boundlessness,' Moussavi says. Anigre wood walls are incised with Kufi calligraphy, a strategy that provides additional ornament while absorbing sound.

This sense of boundlessness continues outdoors, where visitors can discover nine acres of gardens by Nelson Byrd Woltz. 800 Texas trees and countless perennials meet symmetrical Islamic gardens, traversed by triangle-patterned walkways. You can discover Prairie grasslands near the Buffalo Bayou, live oaks on a terrace and numerous reflecting pools throughout the grounds.

'It's something new,' Moussavi explains of this shining new building. 'It's not about getting stuck in traditionalism and its representation, but using historical ingredients and giving them a new life.'