In memoriam: IM Pei (1917-2019)

Architect of the Louvre Pyramid and the Bank of China in Hong Kong, IM Pei was a rare beacon of rigorous yet refined creativity rooted in an analytical approach to time, place and purpose. Widely admired, Pei received every important professional award over his career including the gold medal of the American Institute of Architects (1979) and the Pritzker Prize (1983)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

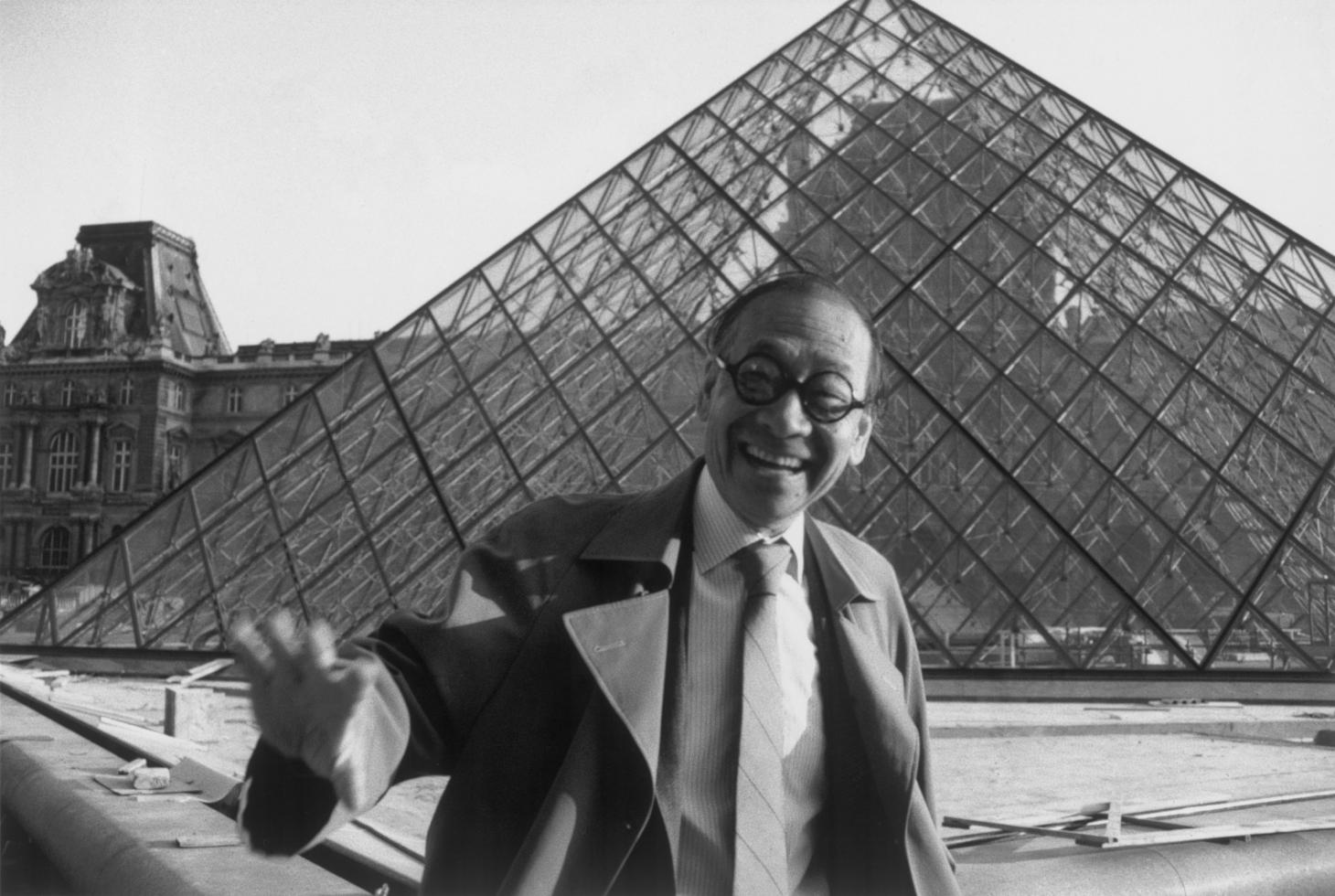

Ieoh Ming Pei, the Pritzker-prize winning Chinese-American architect renowned for his refined yet ground-breaking buildings has passed away at the age of 102. Although he leaves an indelible imprint on the architecture and urban fabric of his adopted country, America, many of his best-known works, such as the controversial installation of glass pyramids in the Louvre courtyard in Paris and Hong Kong’s 71-storey Bank of China skyscraper – a tower of steel and glass triangles – made him world-famous.

Instantly recognisable by his owlish tortoiseshell glasses, Pei was born into a prominent banking family in pre-revolutionary China on 26 April 1917. In 1935, aged 17, he moved to America to study architecture and engineering, first at the University of Pennsylvania and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), before attending Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, under experimental Bauhaus modernists Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. Although he had every intention of returning home, the outbreak of the Second World War meant he remained in America, where, in 1941, he became a citizen.

Pei claimed he was not proficient at sketching (he said he formed ideas by ‘drawing’ in his mind); yet his architectural vision was always evident. His thesis was the design of an art museum for Shanghai that avoided stereotypical Chinese architectural details and motifs, yet subtly expressed the quintessential archetype through the arrangement of the walls and the series of gardens – leading Gropius to later acknowledge there was room within the modernist vocabulary to imbue culturally-specific ideas.

Completed in 1990, the Bank of China designed by Pei stands at 70 storeys high and at the time of its completion was the tallest building in Asia.

After graduation, he worked for the US National Defence Research Committee and then in 1948, joined the flamboyant American real-estate developer William Zeckendorf, an experience Pei said was an invaluable lesson in understanding architecture’s relationship with real estate and politics.

In 1955, he opened his own architecture firm in New York, now known as Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, and quickly became celebrated for his elegant, powerful designs for everything from museums to commercial and residential buildings. Civic projects were important to him and he used his considerable personal charm and networking skills to snap up plum commissions including the JFK Presidential Library in Boston.

He was an architect of subtle contradictions: famous yet under-recognised, pragmatic yet insistent, disciplined but not afraid of breaking the rules.

Aric Chen

Pei’s innate sense of geometry (the triangle, which he saw as a timeless form, especially was a recurring theme) and sculptural form was often associated with modernism, usually expressed in steel, glass and concrete. However, his approach, undeniably influenced by his Chinese roots, defies such simple classifications. In an unpublished interview with the art curator, critic and historian Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2005, Pei explains how his first 17 years in China influenced the rest of his life and career. ‘My education is Chinese. When you get to that age, you are already formed. You may not already know it.’

Pei always began a project with what he called ‘a blank page’, eschewing preconceptions and instead focusing on the site’s circumstances, climate, history and people. This went far beyond mere lip service to a particular context: in 1989, when commissioned to renovate the Musée du Louvre in Paris, Pei did not draw a single line until he had spent four months, most of it incognito, at the Louvre, and reading French history.

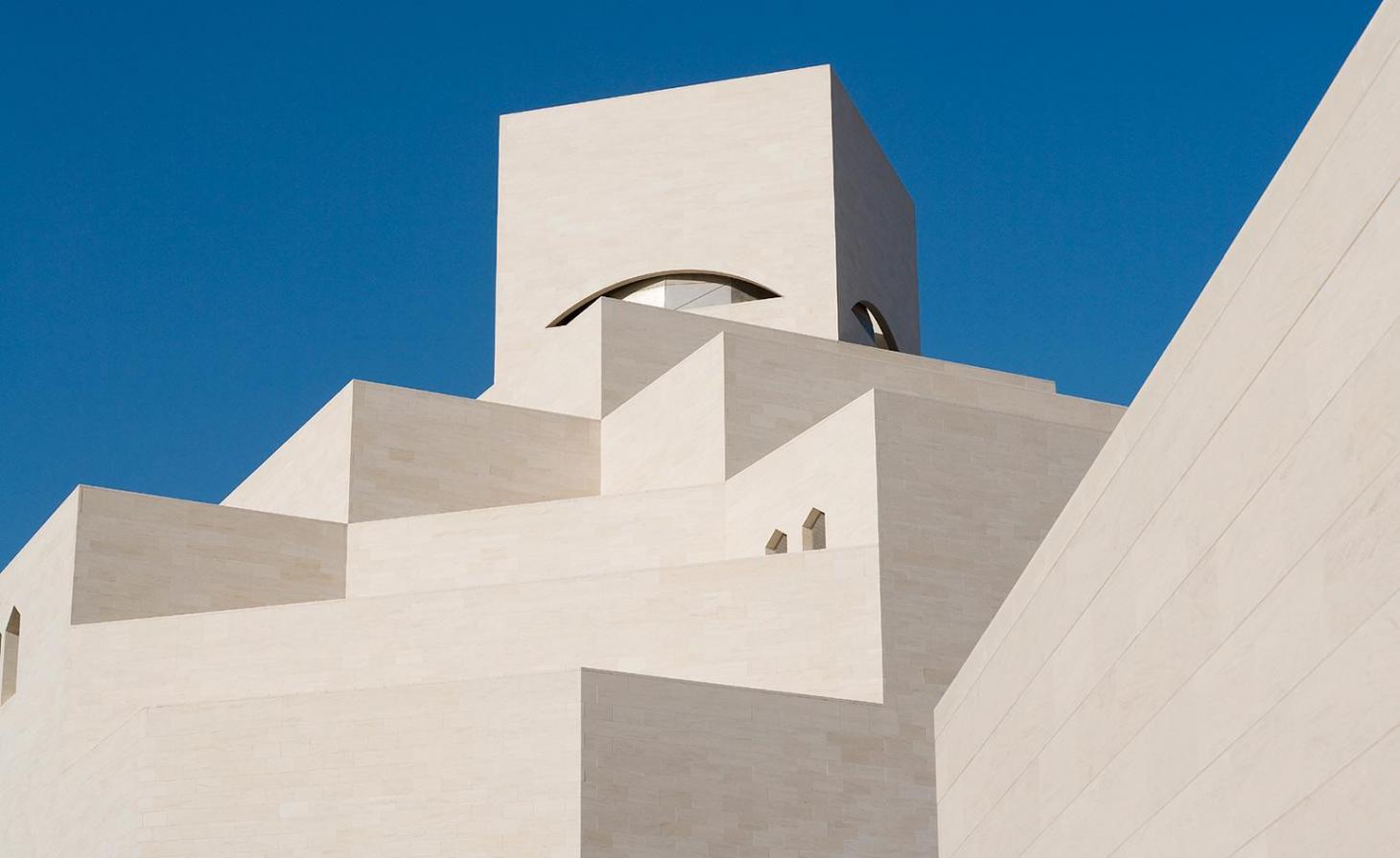

The sculptural, geometric peaks of the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, designed by Pei.

His design, which included a large glass pyramid in the museum’s Cour Napoleon, created a new entrance into a subterranean concourse and was honoured by The American Institute of Architects in 2017 with the AIA 2017 25 Year Award, a prize awarded annually to a building that ‘has stood the test of time for 25-35 years, and continues to set standards of excellence for its architectural design and significance.’

‘I’m not a brand. All my projects are different. Why? It’s much richer if you learn first and work later,’ he told Obrist.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Pei was the first recognised American architect to work in China when the country was beginning to reopen in the 1970s, marking his return after four decades with the Fragrant Hill Hotel outside Beijing. The low-rise building arranged around courtyards stands in stark contrast to his futuristic Bank of China building in Hong Kong which immediately redefined the city’s skyline with its highly complex, unapologetically abstract angular form. It remains one of Pei’s finest and most original skyscrapers. As Pei explained to Obrist, he felt no need to make the building look Chinese: ‘To do a skyscraper, you should forget about Chinese history. There’s no connection.’

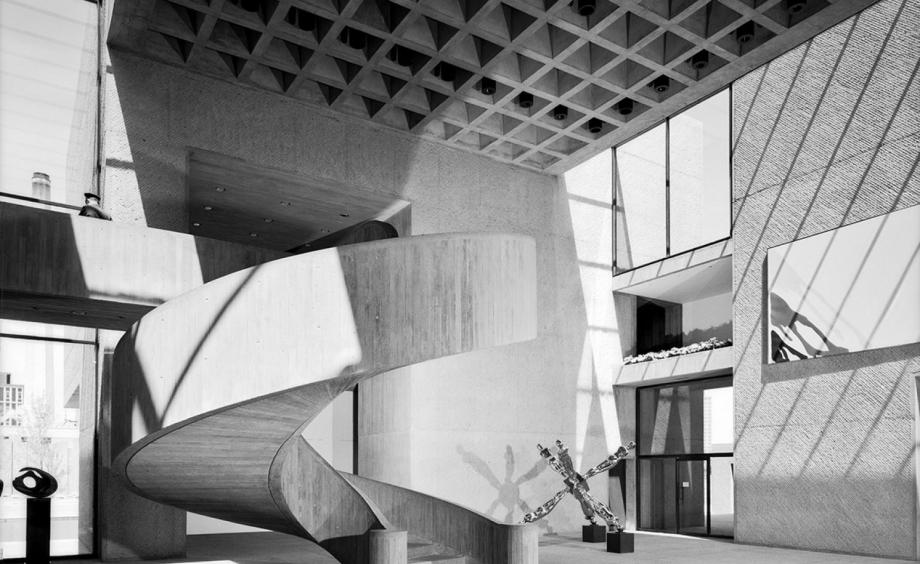

The interior of the Bank of China Tower lobby reveals the structural system of the building and the slim steel supports.

‘One of the things I most appreciate about Pei is how he negotiated the modernist strictures of his time to create an architectural language that was not just formally inventive, but also imbued with cultural meaning,’ says Aric Chen, curatorial director of Design Miami and curator-at-large of M+. ‘He was an architect of subtle contradictions: famous yet under-recognised, pragmatic yet insistent, disciplined but not afraid of breaking the rules.’

Although Pei retired from full-time work in 1990, he continued to win sought-after architectural commissions including Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art and the Miho Museum, where he embedded the museum within a forested mountain near Kyoto. After decades at the head of a large architectural practice, he saw this period as one that allowed him to indulge in creative projects.

In his eighties, he returned to his ancestral family home in Suzhou, China where with the Suzhou Museum he once again had the chance to incorporate China’s rich architectural traditions with modern design.

It is easy to say that the art of architecture is everything, but how difficult it is to introduce the conscious intervention of an artistic imagination without straying from the context of life.

- IM Pei

‘It was not just a project to him. He was very aware of Chinese culture,’ says Shanghainese architect Ling Bing. ‘One of the most important things he did then was to remind China of its cultural heritage. He knew that in a fast developing culture you don’t always pay enough attention to this. He would say, “It doesn’t have to be modern, it has to be sensitive.”’

Pei and his wife Elaine, who was a classmate at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, married in 1942. The couple shared a lifelong love of art, becoming close friends with many, including Jean Dubuffet, Willem De Kooning and Barnett Newman. Pei elevated his passion for art to a consideration of space by commissioning great artists like Miró, Picasso and Henry Moore.

The National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado, was completed in 1967 and was one of Pei’s first widely recognised, major architectural acheivements.

During his 60-year career, Pei received every important professional award including the gold medal of the American Institute of Architects (1979) and the Pritzker Prize (1983) where, in his acceptance speech, he said: ‘The chase for the new, from the singular perspective of style, has too often resulted in only the arbitrariness of whim, the disorder of caprice. It is easy to say that the art of architecture is everything, but how difficult it is to introduce the conscious intervention of an artistic imagination without straying from the context of life.’

In an era of so-called starchitects, Pei was a rare beacon of rigorous yet refined creativity rooted in an analytical approach to time, place and purpose.

Pei is survived by his sons Chien Chung (who goes by ‘Didi’), Li Chung, (who goes by ‘Sandi’) who run Pei Partnership Architects, and his daughter Liane. His son T’ing Chung passed away in 2003.

IM Pei’s interior of the Everson Museum. Located in Syracuse, New York, the building was completed in 1968.

Catherine Shaw is a writer, editor and consultant specialising in architecture and design. She has written and contributed to over ten books, including award-winning monographs on art collector and designer Alan Chan, and on architect William Lim's Asian design philosophy. She has also authored books on architect André Fu, on Turkish interior designer Zeynep Fadıllıoğlu, and on Beijing-based OPEN Architecture's most significant cultural projects across China.