We explore Horace Gifford’s modernist legacy on Fire Island

We celebrate New-York-beach-house-modernist Horace Gifford’s hedonist hideaways, revisiting a story from the Wallpaper* archives, which first appeared in July 2013

Horace Gifford, the designer of a series of modest but highly influential beach houses in Fire Island Pines, a small town on a spit of land some 50 miles east of New York City, was known for his irreverence. According to Christopher Rawlins, author of the book Fire Island Modernist: Horace Gifford and the Architecture of Seduction, he once told a wealthy gay patron, for whom he designed a house in 1965, ‘You will now have 20 closets to come out of.’

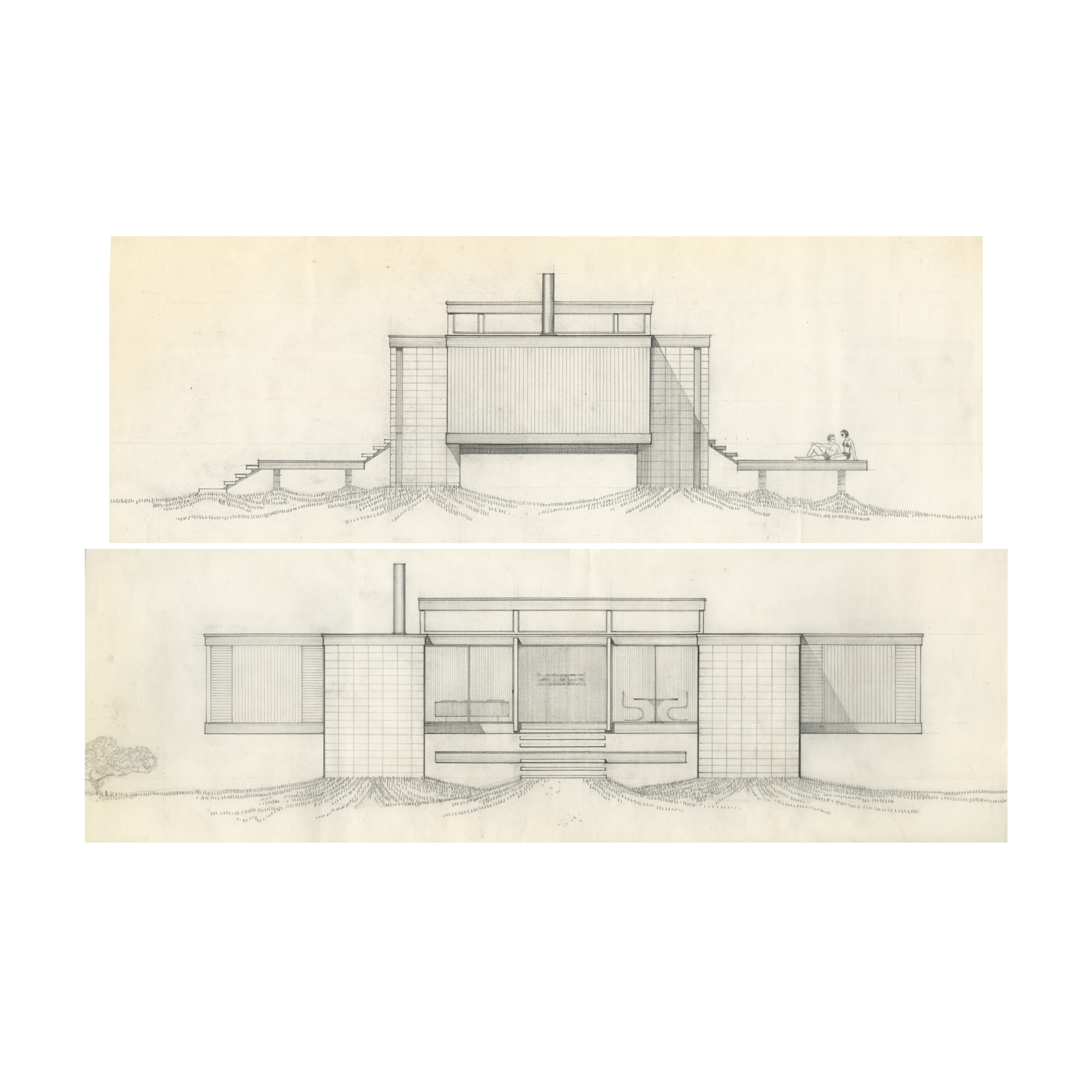

In fact, most of Gifford's clients were already out of the closet – or as out as they could be in the 1960s and 1970s – as members of a social set that was transforming Fire Island into a gay paradise. But if Gifford provided one of them with 20 closets, it was because his floorplan required 20 wooden piers, part of an astonishingly elegant composition derived in part from Louis Kahn. It wasn’t about the closet space. Gifford's houses, which averaged about 100 sq m, were emblematic of a time when even clients as rich as Calvin Klein were weekend minimalists. Their beach houses were not extensions of city life, with all its complications, but more like escape pods, with decks spread out around them like landing pads.

Luck House: built in Bridgehampton, New York, in 1967 for cell biologist David Luck, the cruciform shape is a classic, early Gifford layout.

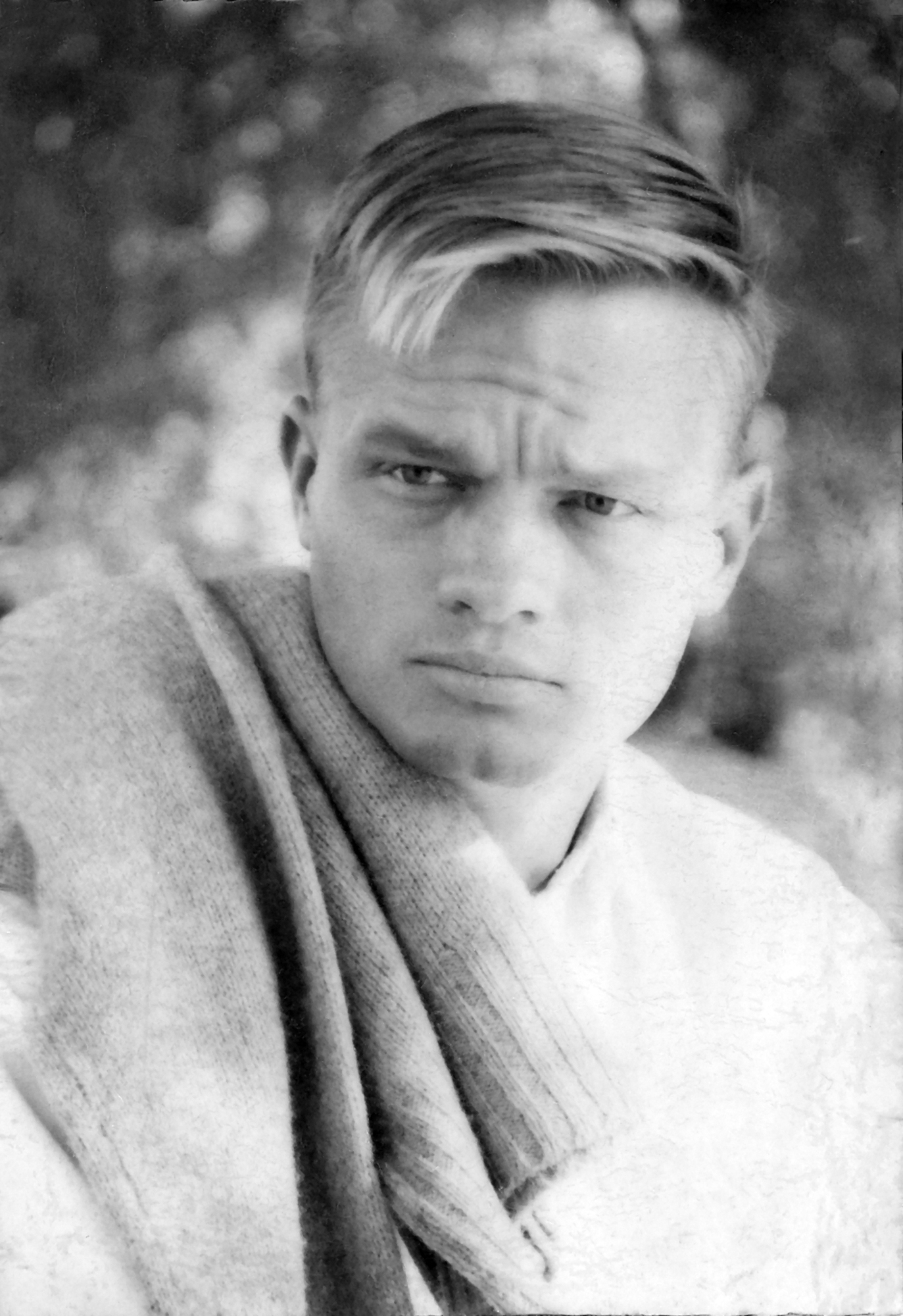

When Gifford arrived on Fire Island in 1961, not yet 30, two of the island’s 18 communities had significant gay populations: Cherry Grove, where the poets WH Auden and Stephen Spender vacationed with the novelist Christopher Isherwood through the 1940s; and Lone Hill (renamed the Pines in the early 1950s), where larger lots attracted a wealthier crowd. But there were few houses of any architectural note. As Rawlins writes, they were mostly ‘mean, prefabricated wooden cottages with tiny windows, delivered on barges and dragged across the fragile dunes to rest upon scrums of skinny wooden pilings. What was left of the dunes was often scraped away to “improve” views.’ Gifford, who was sometimes called the best-looking boy on the beach, attracted the attention of gay (and straight) property owners, who were looking for something more permanent, and who gave him the chance to spread his wings. (In Rawlins’ account, he literally seduced his first client away from Andrew Michael Geller, the architect who subsequently achieved renown in the Hamptons, 20 miles to the east.)

Gifford's polestars were Kahn and Paul Rudolph, both of whom were creating an architecture that was rigorously geometric and yet wildly inventive. (Gifford had fallen under the latter’s spell when Rudolph was designing beach houses in Sarasota in the 1950s; he later met Kahn while studying at the University of Pennsylvania, where Kahn was a leading light.)

Gifford circa 1960

Some of Kahn’s buildings were designed with small enclosures (including stairwells and mechanical spaces) attached like barnacles to larger rooms – what he referred to as ‘served’ and ‘servant’ spaces. From that basic idea, according to Alastair Gordon, author of Weekend Utopia (the classic source on Long Island’s midcentury modernist architecture), Gifford pushed the boxes out with ‘odd angles and flaring floor plans that shielded, revealed, twisted and turned.’

Inside the houses, Gordon continues, ‘hide-and-seek expanses of glass, skylights, floor-to-ceiling mirrors, prurient lines of sight, sunken living rooms and lurid conversation pits turned Gifford's houses into Kabukiesque stage sets for concealment and exposure, light and shadow, inviting voyeuristic tendencies’. One obvious truth: his clients, who for the most part didn’t have children, could allow him to be experimental with living arrangements. And so, he started with simple forms and added, in Rawlins’ words, ‘jazzy improvisations on modernist themes’.

Two of his more famous contemporaries, Charles Gwathmey and Richard Meier, built their first houses on Fire Island; Gifford, who never officially became an architect, designed enough houses on Fire Island – 60 of them between 1961 and 1981 – to give the island its signature architectural style. He died of an Aids-related illness in 1992, but most of his houses survive, in modified form – including the Luck House, a cruciform cottage built in the Hamptons. The house has been lovingly restored by its current owners, Richard Evans and Kim Heirston. Barely larger than a garage, it still packs an architectural punch: a symmetrical bar-shaped enclosure intercepted by front and back decks, which give it its distinctive cross shape.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Rosenthal House: designed in 1972 for Robert and Gladys Rosenthal in Seaview, New York, the house’s diamond-shaped living room features a bright orange fireplace.

For Rawlins, a Princeton-trained architect, the fascination with Gifford began in the early 2000s when, during weekends on Fire Island, he began knocking on the doors of houses he found intriguing, architecturally. (‘It’s amazing how welcoming strangers are out there if you wear a tight enough T-shirt,’ he jokes.) Most of the houses he liked turned out to be by Horace Gifford. Soon his vacations were devoted to poking around Gifford houses and, eventually, searching through a garage (owned by an artist who had befriended Gifford) filled with the architect’s archives. ‘Here sat a life’s work, hastily rescued from the bloodless ministrations of estate liquidators during the chaotic nadir of the Aids epidemic. That evening, under the flicker of an old-fashioned slide projector, dozens of ingenious homes flashed before me, tucked into lightly settled, utopian dunescapes,’ writes Rawlins. ‘I was smitten and determined to introduce this work to a broader public.’

What followed was research into not only the houses, but also Gifford's life – which was as troubled on the inside as it appeared idyllic on the outside. He spent much of the year on Fire Island in a house of his own design but suffered from manic depression and began a decline long before Aids took its physical toll. Rawlins uncovered hundreds of archival photos, some used in magazine spreads, which extolled the architecture but described the clients, if at all, as ‘confirmed bachelors’, largely obliterating the milieu for which the houses were conceived.

Rosenthal House: exterior detail.

Rawlins interviewed about 35 of Gifford's clients (seven of whom still own their Gifford houses). In every case, he writes, ‘they offered alternately poetic and salacious accounts of the young, handsome, and fiercely talented architect who once had the run of this island.’ Some remember Gifford turning up to business meetings in his Speedos. (He had grown up in Vero Beach, Florida, the product of an era when the emphasis in ‘beach house’ was very much on ‘beach’). One anecdote that didn’t make the book concerned a black-tie party hosted by Gifford at which the only attire was black ties.

One client who wouldn’t talk was Calvin Klein, who bought a Gifford house in 1977, then hired the architect to expand onto the lot next door, where he tore down an existing house and replaced it with a pool and gym. Gifford lined the pool in black, with a mirror at one end to extend its apparent length. But as it reached its apogee, the hedonistic era was ending. Gifford left Fire Island in the mid-1970s; a few years later Klein decamped to the Hamptons, where he married and retreated into a life of relative privacy.

Drawing of Luck House, benefiting from the openness and experimental inclination of the summer residents

After leaving Fire Island, Gifford floundered. Samsonite recruited him for an advertising campaign, in which the dashing architect posed in front of his ‘architectural classics’ with an attaché case, but he never produced much work beyond the Fire Island houses, and even there he was largely forgotten by the time Rawlins first visited in 1999. He might have been consigned to obscurity had Rawlins not discovered and fallen in love with his work. In 2007, Rawlins rented a Gifford house and started making near-daily discoveries. When he measured the rooms, he realised they followed the ‘golden ratio’. And when he slid the cushions off the sofa, they perfectly filled the pit in front of the fireplace. Rawlins found himself thinking, ‘I wish I had worked for this man.’ Writing the book was, he says, ‘my apprenticeship with Horace Gifford.’ §

A version of this article first appeared in Wallpaper* 172, July 2013

INFORMATION

Fire Island Modernist: Horace Gifford and the Architecture of Seduction, by Christopher Rawlins, $60, published by Metropolis Books and Gordon de Vries Studio