Twenty modernist houses by Gerrit Rietveld documented in detail for the first time

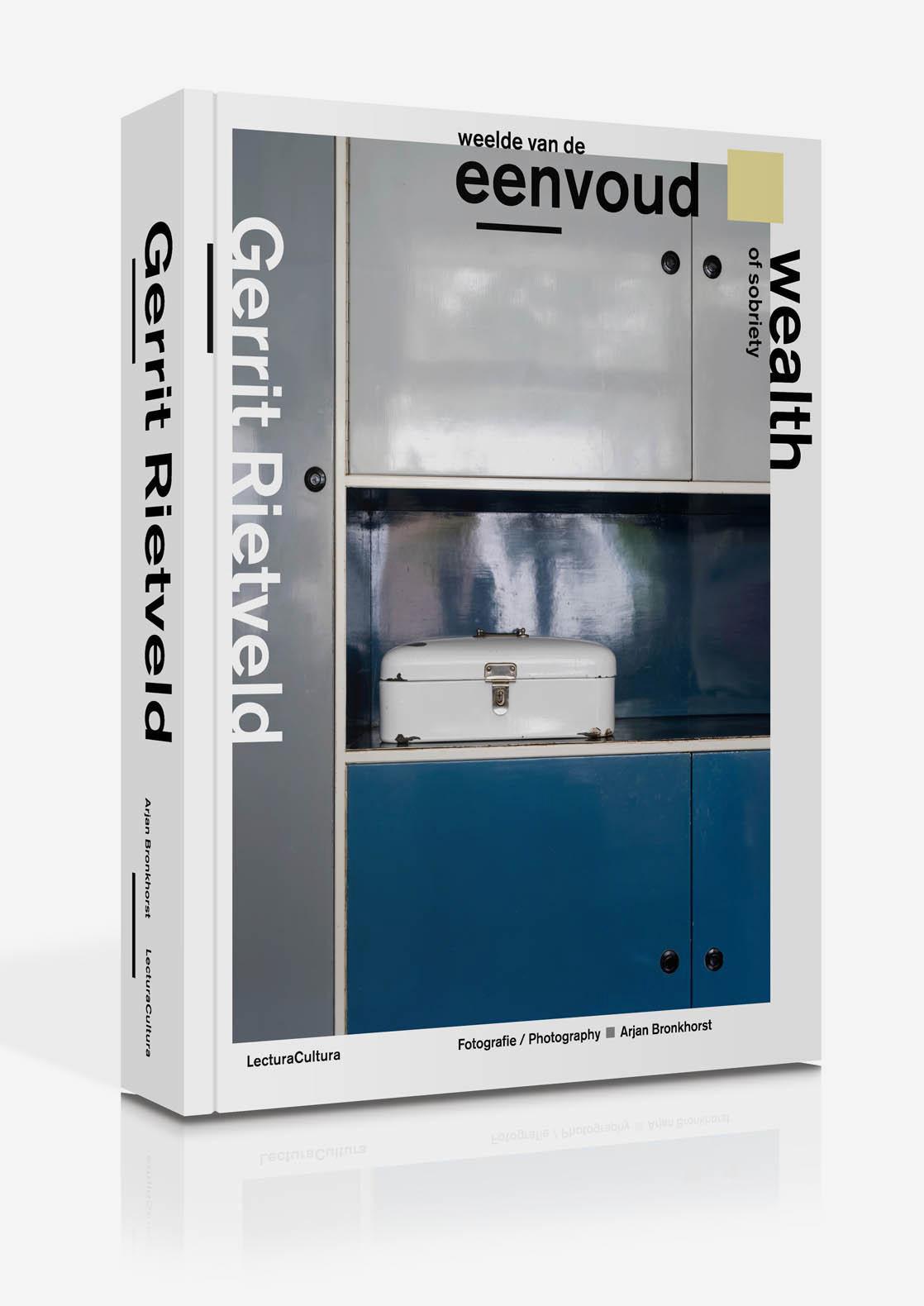

A new photographic book titled Gerrit Rietveld: Wealth of Sobriety celebrates the unique houses of Dutch architect and designer Gerrit Rietveld (1888-1964) – and not just the Schröder House, but a hoard of others too that have been rediscovered. Photographer and publisher Arjan Bronkhorst embarked on two years of research, to visit, capture and compile photographs of these houses into this colourful tome of over 500 pages. Smart colour-blocked design comes courtesy of Haarlem-based studio Beukers Scholma.

The fantastically colourful Schröder House of 1924 in Utrecht was designed and built during a period of Bauhaus school activity, and around the time Le Corbusier built Villa La Roche in Paris. It is the bold modernist monument that people know Rietveld for the most – along with his famous Red Blue Chair, a 20th-century design staple. Famous across the world, it is the only Dutch house on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. Rietveld’s very first house, it set the bar high.

Yet the Schröder house was just the beginning. ‘Like the Red Blue Chair, Rietveld viewed the house largely as an experiment,' the book reads. ‘He called it “a study for the new”. He never repeated the experiment, but by his own admission all his later work was based on the ideas he first developed here’.

Van der Vuurst de Vries’ chauffeur’s apartment, 1928.

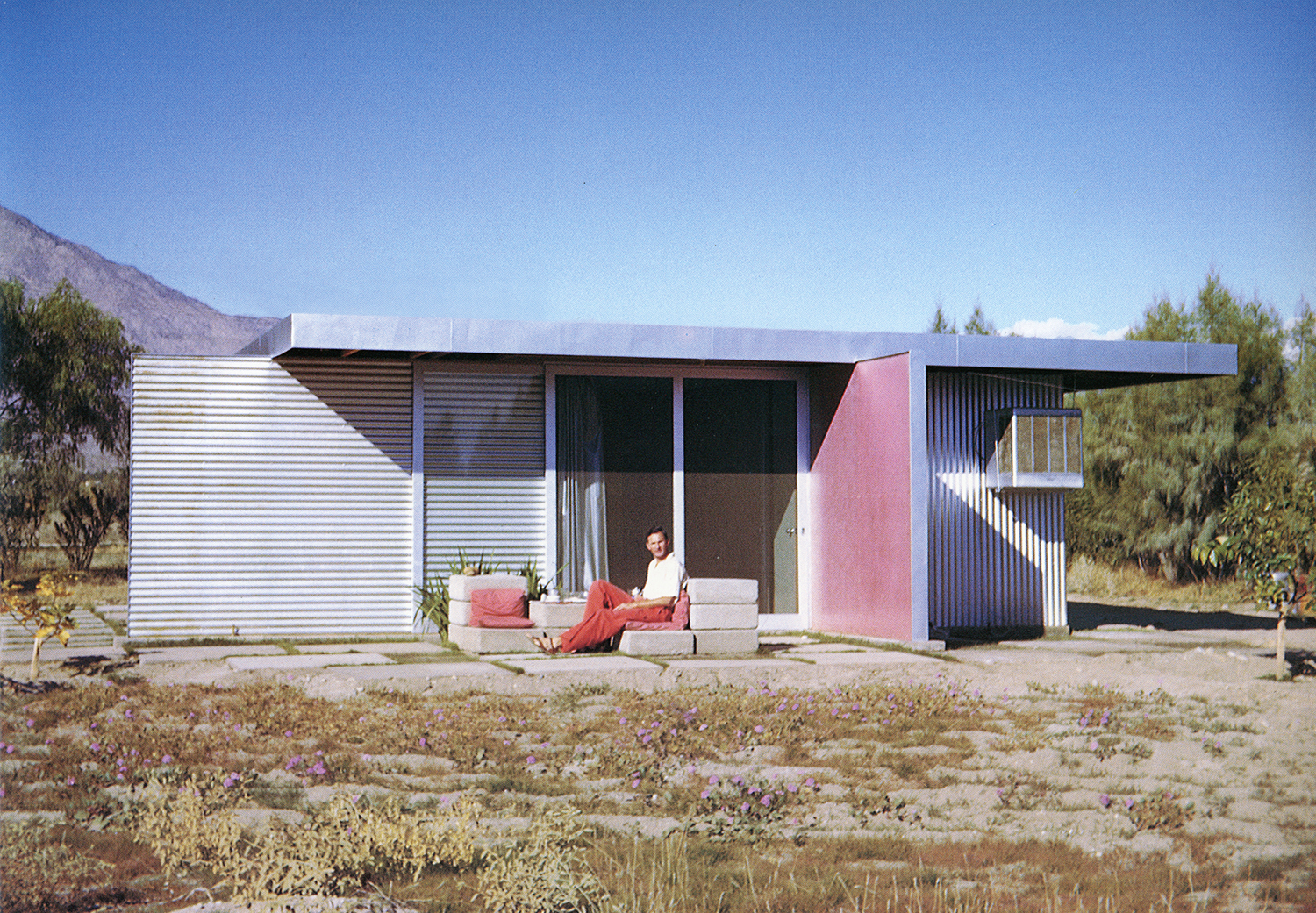

Bronkhorst’s project aimed to capture the depth and breath of Rietveld’s residential career – he had built almost a hundred houses in the Netherlands, and one largely undocumented – until now – in America. It was tough, but he narrowed down his focus to twenty case studies between 1924 to 1964, including the seminal Schröder house and the Parkhurst house in America of course.

What drove Bronkhorst was the urge to discover. ‘My book shows that it is possible to retrieve houses by Rietveld that hardly anybody knows,' he explains. ‘In the case of Corbusier, Mies Van der Rohe or Frank Llloyd Wright such a thing would be unthinkable’.

Staircase at Székely House, 1934.

While the recognisable De Stijl Colour palette was used for the experimental Schröder house, ‘in his post-war houses he tended to use the aesthetic qualities of building materials in a subtle way: simple bricks in various shades of brown, glazed bricks, often white, black or grey, B2 concrete blocks and glass bricks,’ writes Ida van Zijl, a Rietveld expert, in the introduction. Built in the Nieuwe Bouwen style, each house prioritised functionality, with colour and space organised to create a balance between the oppositions ‘safe and free, stimulating and calming’.

The intriguing sub-title to the book ‘Wealth of Sobriety’ references how Rietveld succeeded in making his modest houses feel spacious, by working carefully with colour and light. ‘We could make such progress if people would reject extravagance (…) and would find joy in the wealth of sobriety,’ Rietveld said in 1968.

Van Dantzig House, 1960.

Bronkhorst frames Rietveld’s flat, colourful house exteriors that rival Mondrian’s paintings in their leafy green surroundings. There are many modernist delicacies to consume, from the glass framed Hildebrand House that sits like a lantern in the tranquil landscape of Blaricum, to a flat little cottage with a sloping porch roof in Arnhem. A boxy pre-fab chauffeur’s apartment connected to an existing house in the suburbs of Utrecht presents an example of Rietveld refining his style, while a curved dark-green timber summer house with a thatched roof in the Loosdrecht Lakes shows his interest in combining vernacular styles with modernist values.

RELATED STORY

The interiors reveal more of Rietveld’s artistry – as well as organic staircases, complex conundrums of in-built storage systems and creative bathroom fittings, Bronkhorst holds a fascination with unique door handle details. He picks out the layered moments where bricks meet tiles, textured glass finds its frame, and where peeling paint hits raw material in brilliant contrast. A rarely seen discovery is the Parkhurst house in Ohio, Rietveld’s only house outside the Netherlands. Bronkhorst found the house in ‘bad shape’ yet still delighted at the clear evidence of Rietveld's hand – trademark stripes of red and yellow mark the exterior, while a black-painted steel spiral staircase connects a double height living room to the upper level. ‘Rietveld never visited the house, because he was banned from entering the country owing to his alleged communist sympathies,’ says Bronkhorst, who stayed in the house for two days during his research trip.

As well as his architecture, the book explores Rietveld’s life and character with both facts and anecdotes. A foreword written by the grandchildren of Gerrit Rietveld, Wim Rietveld and Martine Eskes, begins to build up the portrait, that gradually develops through his theories on architecture and his relationships with his clients. He comes across as a charismatic, creative and principled with a stubbornness that Ida describes as ‘amicable obstinacy’.

Yet one of Bronkhorst's discoveries was that perhaps he wasn't always a stubborn as he is sometimes described, and that the success of the design process was influenced by his social relationships with his clients: ‘Rietveld tended to attract intellectual clients such as artists, writers, musicians, professors and doctors, who were all interested in his avant-garde ideas and designs. It is likely that these clients influenced Rietveld’s designs to some extent. Take Van Dantzig House in Santpoort (1960) for example; you enter the house through a square concrete tunnel. Remarkable and unique among Rietveld’s houses, it turned out to be an idea devised by the client, Huug van Dantzig, himself.’

Interviews with current residents of the houses, some original clients who are now in their 80s and 90s, reveal intimate experiences of working directly with him, and what it's like to live in a Rietveld house day to day. Their portraits also feature, as well as many traces of living – and decay too.

Working for the Hendrick the Keyser society – a Dutch organisation that preserves and maintains valued architectural and historical properties – for nearly ten years, Bronkhorst developed his eye for the ‘monumental interior’. Yet he has also developed another fascination along the way: ‘I am not only interested in the buildings themselves but also very much interested in the people that live in the works of architects. I introduced this way of working with my bestseller Grachtenhuizen (Amsterdam Canal Houses), in which I portrayed the people that live in the majestic canal mansions alongside Amsterdam's ring of canals once built by members of the mighty 17th century VOC (Dutch East India Company).’

The Parkhurst house in Ohio, 1961.

Interior of the double height living space at Parkhurst house in Ohio.

Interior of Slegers house, 1955.

The Verrijn Stuart Breukelen Summerhouse, 1941.

Interior of the Verrijn Stuart Breukelen Summerhouse with furniture designed by Rietveld.

Owner Gerda Slegers inside the Slegers house.

The Van den Doel House, 1959.

The Hildebrand house, 1935.

The Mees House roof, 1936.

Grey and white in-built storage designed by Rietveld at the Bláha House, 1957.

INFORMATION

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Gerrit Rietveld: Wealth of Sobriety (Weelde van de Eenvoud), Dutch/English, €59, is published by Lectura Cultura. For more information, see the Lectura Cultura Books website and photographer Arjan Bronkhorst’s website

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.

-

Inside the fantastical world performance artist, Darrell Thorne

Inside the fantastical world performance artist, Darrell ThornePerformance artist Darrell Thorne straddles multiple worlds, telling stories through transformation, reinvention and theatrical excess

-

Mostly armless: life with the Roborock Saros S70 and taking a (shallow) step into the future

Mostly armless: life with the Roborock Saros S70 and taking a (shallow) step into the futureThe arm-equipped Roborock Saros Z70 robot vacuum dusts, mops and even cleans up your messy household. So why did it feel like adding a demanding new family member?

-

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekSummer holidays are here, with Wallpaper* editors jetting off to some exceptional destinations, including highly recommended Mérida in Mexico. Then it’s back to work, or, for one editor, back to school…

-

Ma Yansong's latest project is anchored by a gleaming stainless steel 'tornado'

Ma Yansong's latest project is anchored by a gleaming stainless steel 'tornado'The new Fenix museum in Rotterdam, devoted to migration, marks MAD's first European cultural project.

-

Modernist Travel Guide: a handy companion to explore modernism across the globe

Modernist Travel Guide: a handy companion to explore modernism across the globe‘Modernist Travel Guide’, a handy new pocket-sized book for travel lovers and modernist architecture fans, comes courtesy of Wallpaper* contributor Adam Štěch and his passion for modernism

-

Wild sauna, anyone? The ultimate guide to exploring deep heat in the UK outdoors

Wild sauna, anyone? The ultimate guide to exploring deep heat in the UK outdoors‘Wild Sauna’, a new book exploring the finest outdoor establishments for the ultimate deep-heat experience in the UK, has hit the shelves; we find out more about the growing trend

-

At the Sony World Photography Awards 2025, architecture shines

At the Sony World Photography Awards 2025, architecture shinesThe Sony World Photography Awards 2025 winners are announced, offering a visual feast in the Architecture & Design category

-

Portlantis is a new Rotterdam visitor centre connecting guests with its rich maritime spirit

Portlantis is a new Rotterdam visitor centre connecting guests with its rich maritime spiritRotterdam visitor centre Portlantis is an immersive experience exploring the rich history of Europe’s largest port; we preview what the building has to offer and the story behind its playfully stacked design

-

Ten contemporary homes that are pushing the boundaries of architecture

Ten contemporary homes that are pushing the boundaries of architectureA new book detailing 59 visually intriguing and technologically impressive contemporary houses shines a light on how architecture is evolving

-

Take a deep dive into The Palm Springs School ahead of the region’s Modernism Week

Take a deep dive into The Palm Springs School ahead of the region’s Modernism WeekNew book ‘The Palm Springs School: Desert Modernism 1934-1975’ is the ultimate guide to exploring the midcentury gems of California, during Palm Springs Modernism Week 2025 and beyond

-

Meet Minnette de Silva, the trailblazing Sri Lankan modernist architect

Meet Minnette de Silva, the trailblazing Sri Lankan modernist architectSri Lankan architect Minnette de Silva is celebrated in a new book by author Anooradha Iyer Siddiq, who looks into the modernist's work at the intersection of ecology, heritage and craftsmanship