Inside the fantastical world of performance artist, Darrell Thorne

Performance artist Darrell Thorne straddles multiple worlds, telling stories through transformation, reinvention and theatrical excess

Michael Reynolds - Producer

Darrell Thorne appears like a glitch in the Matrix. Ornate and mirrored, headdress high, often on prosthetic stilts, body painted, horned, winged, caped, crowned (sometimes all at once), he doesn’t enter so much as materialise. Not quite male or female, not entirely human or alien, he moves through space as something in-between. A guest from another realm, summoned by those who find the visible world insufficient. Gala committees, fashion houses and private clients seek him out for something that floats beyond the boundaries of reality.

Part character designer, part performance artist, pure spectacle, Thorne turns flesh into fantasy. When pop’s grandes dames (Liza, Cher, Madonna) crave something otherworldly, they turn to his singular talents. ‘Sometimes people want more than beauty,’ he says. ‘They want to feel mythic.’

Thorne grew up in small-town America and his family moved often (Alaska, Arkansas, Missouri). He was the youngest of five, raised under the strict codes of the Missionary Baptists. His grandfather was a preacher. His parents were devout. Television was forbidden. Hell was not a metaphor.

His escape wasn’t rebellion, it was books.

The first artist who mattered to him was Chris Van Allsburg, the writer and illustrator behind Jumanji and The Polar Express. From there he reached Narnia, Middle-earth, and beyond. Stories became his passport into wilder, more fantastical dimensions, but within his oppressive upbringing, there was a twist: Thorne’s father, despite his religious fundamentalism, was also an amateur artist.

The contradiction was striking. By day, he enforced a world view that left no room for the frivolous. At night, he built things. That paradox left an outsized mark on Thorne, giving him an early fluency in contradiction – an instinct for holding opposites without needing to choose between them. As a child, he once sat through a sermon by Fred Phelps, the notoriously homophobic founder of the Westboro Baptist Church.

‘Very, very strict,’ he says when describing his formative years. ‘Through religious dedication, our family could be saved, but everyone else was going to burn.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The severity of his upbringing had unintended side effects: it stirred the depths of his imagination. ‘The repression built slowly, but unavoidably,’ Thorne says. ‘After being compressed for so long, I needed to express myself. I needed to be seen.’ His early life is a textbook case of how unaccepted adolescent desire, and the ache of queer isolation, can turn a child into a world-builder.

His adult rebellion came in stages: college dance classes, the Hubbard Street Dance Company in Chicago, go-go platforms in LA, and eventually New York. By day, he worked in healthcare as an administrator at a cancer centre. By night, he worked at The Cock, half-naked, half-painted, wholly unclassifiable. ‘I wasn’t a drag queen. I wasn’t a muscle go-go boy. I was something else.’

That in-between quality began to crystallise through collaboration. Weimar New York, a decadent performance lab, took him in. Among fellow shape-shifters, such as Machine Dazzle, Thorne found the freedom to mutate, exaggerate and transgress. Each night became a provocation: how far could he push it?

The goal was always escalation, each transformation more elaborate than the last. Reinvention became an obsession, an urge that soon required a studio, a space that would allow him to fully execute his vision.

He never had a job description – no existing title seemed to fit. Costume designer felt too flat, too literal. Thorne doesn’t just dress people, he conjures up auras. ‘I’m not just transforming appearances,’ he says. ‘My aim is to transform the energy of the room.’

His work eventually caught the attention of nightlife ringleaders Susanne Bartsch and Brandon Voss. In Thorne, they found a young talent charging into the unknown with courage, ambition and body paint.

Both supported him with opportunities that fostered his development.

‘I’m not just transforming appearances. My aim is to transform the energy of the room.’

Darrell Thorne, performance artist

Nightlife impresario and entrepreneur Daniel Nardicio, one of the first to hire Thorne, recalls, ‘He was never a traditional go-go boy, he was always a performance artist on a platform. He brought a certain je ne sais quoi. It’s been exciting to watch him grow into one of New York’s larger-than-life personalities, and move beyond nightlife into fashion, theatre and acting.’

Somewhere along the way, the requests expanded – he wasn’t just designing looks for himself, he was conceptualising entire characters for full performance troupes. The invitations evolved, too: less underground, more institutional; less queer, more corporate. ‘The gay scene didn’t always know where to put me,’ he says. ‘Straight parties had more money, and less imagination.’

Today, Thorne’s work straddles multiple worlds. He is at once designer, director, performer and storyteller, bringing spirit and unpredictability to spaces often stiff with tradition. His client list reflects a rare ease across extremes, from liberal to conservative, high-minded to high-budget: Brooklyn Academy of Music, Lincoln Center, Bergdorf Goodman, Gohar World, Martha Stewart, Dom Pérignon, Red Bull, Cipriani, Gracie Mansion and RuPaul’s Drag Race, as well as financial firms, including Uprising Capital, Ridge Ventures and Carson Wealth.

‘The gay scene didn’t always know where to put me.'

Darrell Thorne

Watching him in action, a techno Ganesha prancing in a mirrored headdress, sheer neon fabric billowing behind him, the moneyed crowd falls into ecstatic awe. He’s not unlike a court jester. Officially powerless yet granted rare permission to dazzle, disrupt and even critique, from within. His costume signalled both his marginality and his access.

Like the jester, Thorne isn’t there to dismantle the institution, but to enchant it, queering formal events with beauty, absurdity and the kind of fantasy that momentarily suspends the rules. ‘I enter spaces where everyone else is buttoned up,’ he says. ‘And I become the rupture. A beautiful rupture. It gives people permission.’

Not every transformation aims for the sublime. Many luxuriate in camp and theatrical excess. The results aren’t always tasteful, but they aren’t meant to be. Thorne’s sensibility courts the grotesque and the baroque, revelling in maximalism. And yet, in a culture steeped in cynicism, his candid spectacle feels almost illicit, brazen enough to risk being unfashionable. Its power lies there: sincerity barbed with decadence. Now in his forties, Thorne still carries a boyish, wide-eyed, almost mischievous exuberance. He has lived for years in the Brooklyn neighbourhood of Bushwick in an apartment that feels like a living mood board: surreal, meticulous, strangely durable.

‘I enter spaces where everyone else is buttoned up. And I become the rupture'

Darrell Thorne

Part laboratory, part art installation. ‘Lighting is important,’ he says. ‘So is height. I need room to hang things.’ The kitchen is seafoam green and lit by a gold wrought-iron fixture that, he says, was once a street lamp. ‘Leap and the net will appear,’ reads a ceramic tile on his stove, bought years ago from a former investment banker-turned-ceramist at an art market. He took it, naively maybe, as a sign to quit his job and commit fully to his creative life.

The living room centres on a mural of clouds painted by his upstairs neighbour, artist Matt Austin. The bedroom shimmers with reflective surfaces. Like his creations, the home overlays global and historical references – sacred artefacts drawn from a multitude of cultures and time periods – into a cohesive, unmistakably personal world.

Many of the studio’s details are gifts from his father, including deer antlers from past hunts and feathers from an albino peacock (his father once kept one as a pet).

His father also designed the mirrored ceiling grid where his headdresses hang, their surfaces catching the light in neatly choreographed rows. ‘Today, my parents are extremely proud of me, and of my work,’ says Thorne. ‘They even share my viral TikTok videos with their neighbours.’ The studio hums with the combined energy of the many characters he’s inhabited. Here it becomes apparent how the duality he experienced as a child has manifested in his way of layering beauty and contradiction into a single space. One of his signature contributions to performance is a mirrored headpiece that vertically bisects the face.

When he turns to one side, the other vanishes. It builds on a classic drag conceit – half-male, half-female – but the headdress heightens the extremity and sharpens the illusion. Thorne uses it to stage every kind of pairing: angels and devils, Mother Earth and Father Industry, Vikings and sea witches.

‘The mirrored duet is my invention,’ he says. ‘A lot of people now use something similar, but I’m 100 per cent certain that no one was doing that before me.’

The headdress is a visual manifestation of his lifelong meditation on duality, proof of how naturally Thorne holds contradiction. ‘I’m a Gemini, which I don’t put that much stock in,’ he says. ‘But in so many ways, I contain polar opposites.’

'In moments of political fear and psychic fatigue, beauty can be a lifeline.’

Darrell Thorne

Viewing his extensive archive, it’s clear that his work refuses restraint. The handmade, the excessive, the obsessive – these aren’t indulgences, they’re tactics. It’s not quiet. It’s not respectable. And it feels especially urgent in a country increasingly hostile to anything outside the power structure’s current idea of normal.

This feels like the right moment to ask how he sees his work in a time of rising authoritarianism and perpetual war.

‘Sometimes I feel like, how can I be making this floral skirt when the world is burning?’ he says. ‘But in moments of political fear and psychic fatigue, beauty can be a lifeline.’ He doesn’t offer escape so much as a reminder: a stranger, more bearable world is still possible.

Film directed by Michael Bullock and Bob Hoste. Cinematography: Bob Hoste. Interview by Michael Bullock. Camera assistant: Ian Wishart. Sound design: Duffy Sound.

Correction: The nightclub 'Catch One' referred to in the film was located in Los Angeles, not New York as the film suggested.

Michael Bullock is a Brooklyn-based writer, editor and documentary filmmaker focused on art, design and queer culture. He is the author of Roman Catholic Jacuzzi (Karma 2012) the editor of Peter Berlin: Artist, Icon, Photosexual (Damiani 2019), and co-editor of I Could Not Believe It: The 1979 Teenage Diaries of Sean Delear (Semiotext(e) 2023). Bullock serves as associate publisher of PIN–UP and The Whitney Review of New Writing and is a contributing editor to apartamento.

-

How Isamu Noguchi dissolved the boundaries between art, design and the city

How Isamu Noguchi dissolved the boundaries between art, design and the cityIsamu Noguchi shaped cities, interiors and everyday rituals through design: here’s everything you need to know about the interdisciplinary American modernist who believed art belonged in public life

-

Photographer John Arsenault’s ceramic vessels prove it’s never too late to shift focus

Photographer John Arsenault’s ceramic vessels prove it’s never too late to shift focusAfter years creating portraits, the artist has revealed a series of intriguing and sexually-charged pieces in New York

-

Wallpaper* Architect Of The Year 2026: Lina Ghotmeh, France

Wallpaper* Architect Of The Year 2026: Lina Ghotmeh, FranceAsked about a building that made her smile, Lina Ghotmeh – one of three Architects of the Year at the 2026 Wallpaper* Design Awards – discusses Luis Barragán’s Capuchin Convent Chapel and more

-

Vanessa Beecroft’s ethereal performance and sculpture exhibition explore Sicily’s cultural history

Vanessa Beecroft’s ethereal performance and sculpture exhibition explore Sicily’s cultural historyAt the historic Palazzo Abatellis, Sicily, Vanessa Beecroft has unveiled ‘VB94’, a new tableau vivant comprising a one-time performance and a new series of sculptures, the latter on view until 8 January

-

Subversive artist Cosey Fanni Tutti on individuality and annihilating limitations

Subversive artist Cosey Fanni Tutti on individuality and annihilating limitationsFollowing the launch of her new book Re-Sisters, we speak to Cosey Fanni Tutti about conquering fear through action, stepping into the unknown, and the secret to making art that matters

-

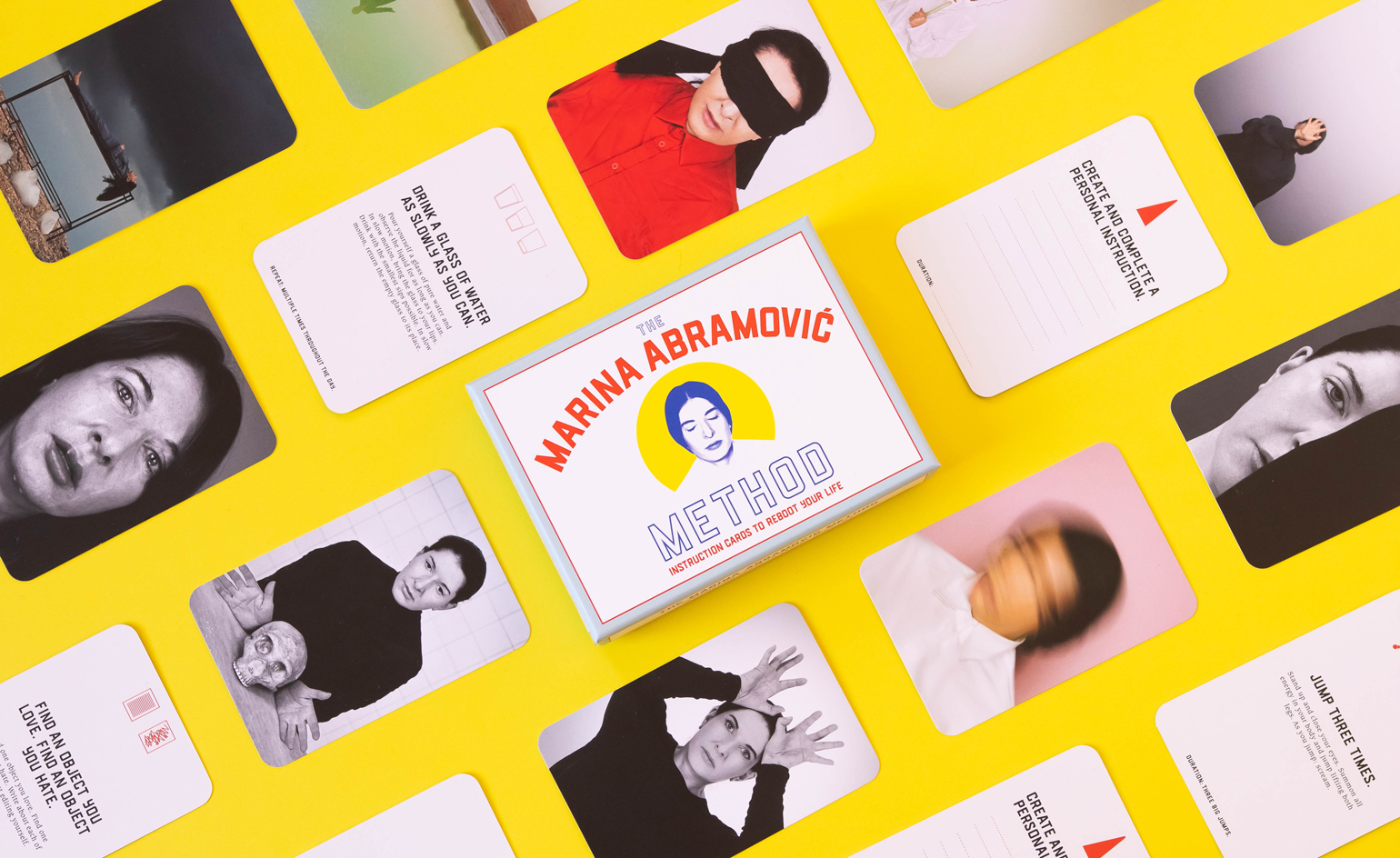

Can the Marina Abramović Method change your life?

Can the Marina Abramović Method change your life?Lady Gaga and Jay-Z are among those who have followed the Abramović Method to reach higher creative consciousness. Now, the artist’s iconic approach has been translated into a series of instruction cards for all. If you don’t try, you’ll never know

-

Ragnar Kjartansson’s dramatic soap opera inaugurates GES-2 in Moscow

Ragnar Kjartansson’s dramatic soap opera inaugurates GES-2 in MoscowIcelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson inaugurates the much-anticipated V-A-C Foundation’s GES-2 House of Culture in Moscow. Santa Barbara – A Living Sculpture is a bold, theatrical work that examines the relationship between Russia and the US

-

Torkwase Dyson and Mark Rothko inaugurate Pace gallery’s new London home

Torkwase Dyson and Mark Rothko inaugurate Pace gallery’s new London homeJust in time for Frieze Week 2021, Pace has opened its much-anticipated Hanover Square gallery with shows by Torkwase Dyson and Mark Rothko

-

Anne Imhof: body language as tool, canvas and concept

Anne Imhof: body language as tool, canvas and conceptAnne Imhof is one of five radical artists chosen by Michèle Lamy for Wallpaper’s 25th Anniversary Issue ‘5x5’ project. In the midst of Imhof’s carte blanche at Paris’ Palais de Tokyo, we explore how she has redefined the concept of body language

-

Watch JR’s poignant procession for Australia’s agricultural emergency

Released for Earth Day 2021, French artist JR’s film, Homily to Country, is an intensely human commentary on the ecological decline of the Darling/Baaka river system in south-eastern Australia

-

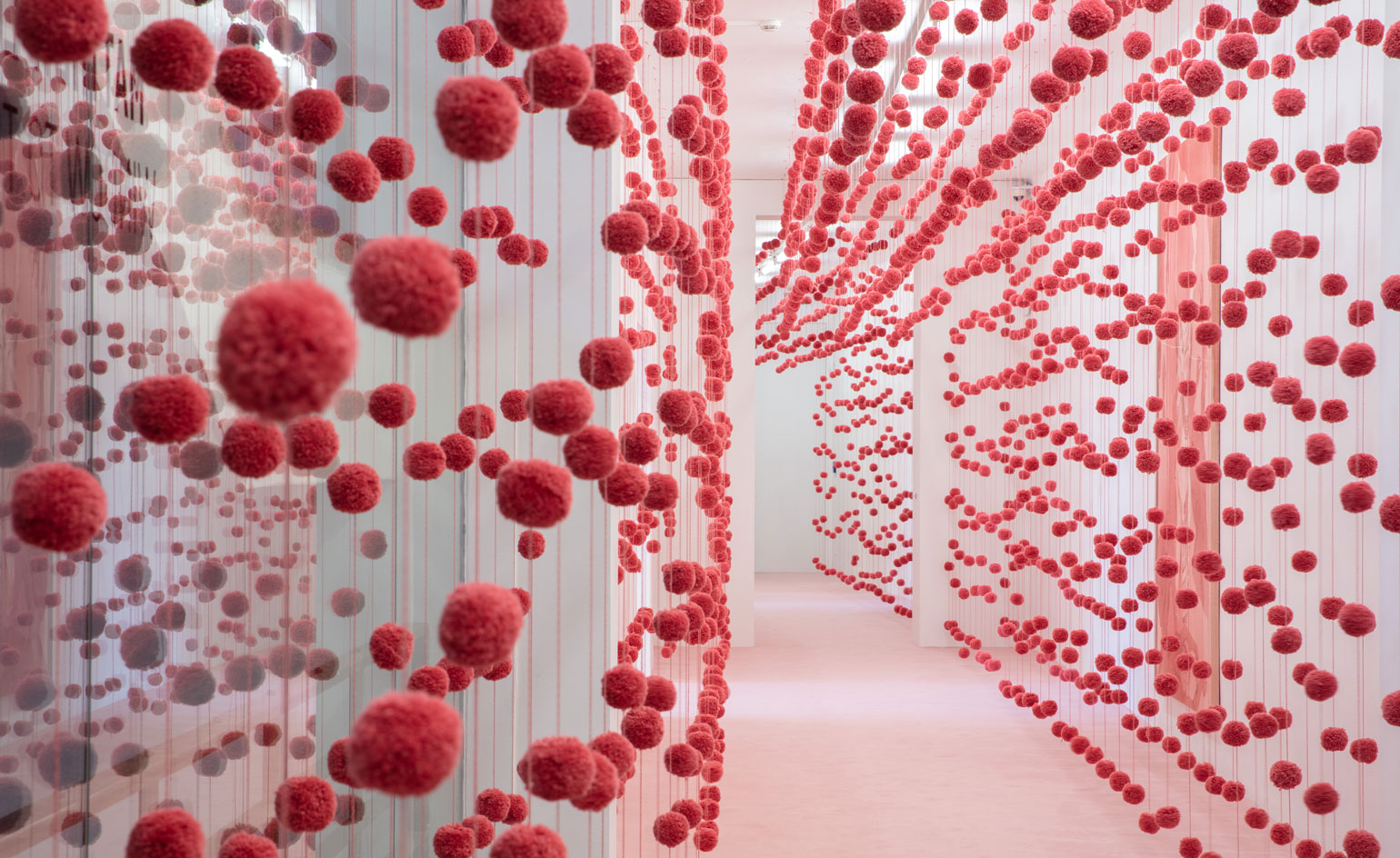

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy’s pink pom-pom utopia

Matthew Lutz-Kinoy’s pink pom-pom utopiaAmerican artist Matthew Lutz-Kinoy transforms Museum Frieder Burda’s Salon Berlin into a strange new world, marking his first solo institutional show in Germany