In memoriam: Will Alsop (1947-2018)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

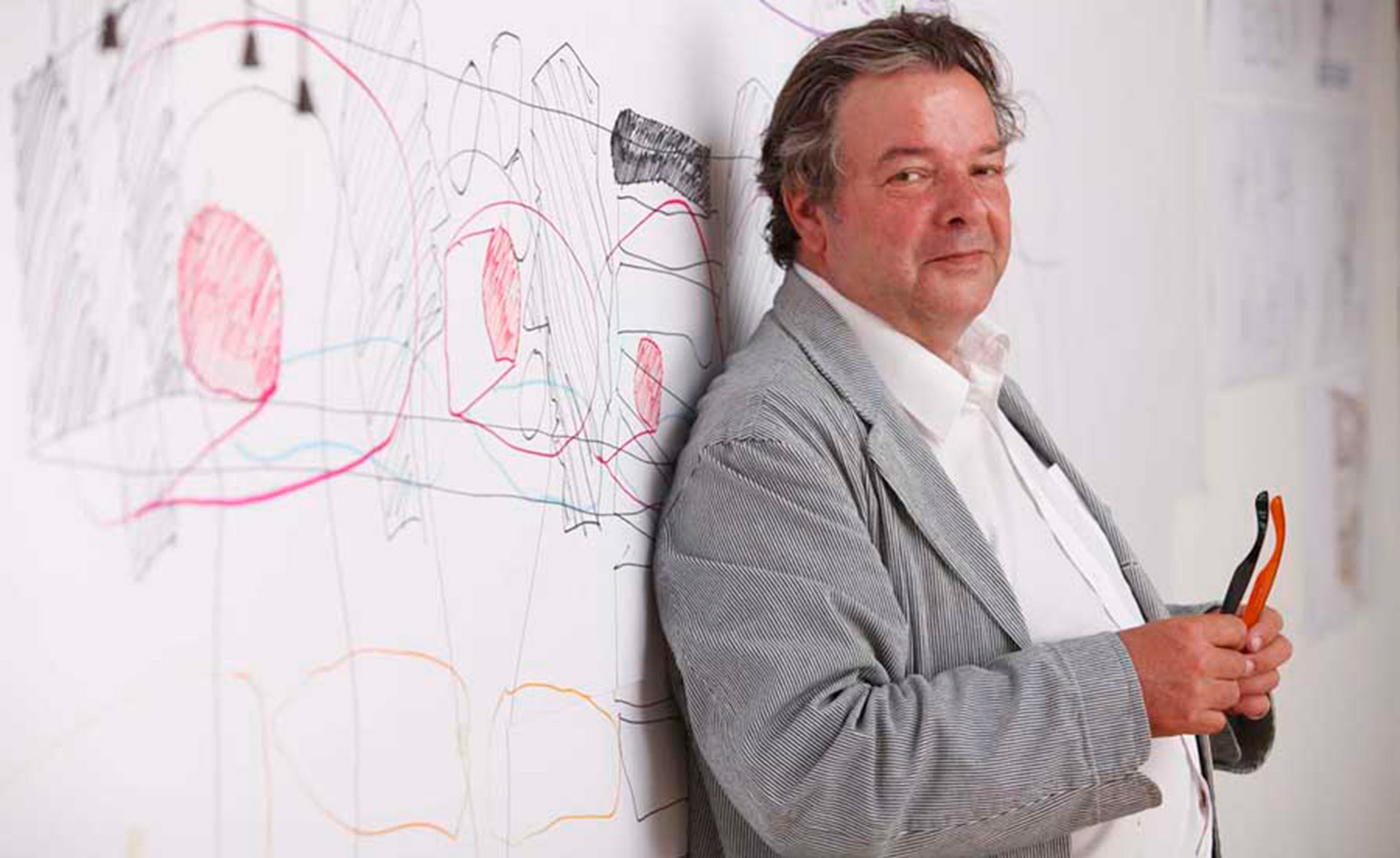

The British architect Will Alsop has died aged 70 after a short illness. The co-founder of aLL Design, who was born in Northampton on 12 December 1947, passed away in hospital on Saturday 12 May.

‘Will has inspired generations and impacted many lives through his work. It is a comfort to know that due to the nature of Will’s work and character, he will continue to inspire and bring great joy,’ says aLL Design director and co-founder Marcos Rosello. ‘He had an exceptional ability to recognise particular strengths in individuals which he would draw out and nurture. His design ethos, essentially to ‘make life better’ is evident in the architecture of his buildings and their surrounding communities. We will miss him greatly.’

Although Alsop never achieved the international fame and fortune of his peers his passion was undiminished. Alsop leaves behind an impressive, albeit succinct, visual legacy, with many projects left unbuilt – his vision was occasionally obscured by over-ambition. His was always an architecture of spectacle adrift in an era of sober conformity, too ostentatious for the modernists, too bold for the high-tech crowd and too wayward and non-conformist for the post-modernists.

Le Grand Bleu, Marseilles, France

His earliest success, a giant town hall in Marseille won during his partnership with Jan Störmer in 1990, was the kind of commission most architects would kill for. The resulting structure, known locally as Le Grand Bleu, stalked above its site like a piece of sci-fi theatre, an office building for local government deconstructed into rich civic theatre.

At this point, Alsop's career could have gone in literally any direction. Le Grand Bleu was critically acclaimed, a welcome mash-up of high-tech's obsession with the architecture of the machine and the playful, boisterous form making of Po-mo. Alsop and Störmer had beaten Foster in the Marseilles competition, a welcome reversal of the decision that left him, at the age of just 23, a runner-up to Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano in the competition for the Pompidou Centre two decades before. The 21st century, it seemed, was his for the taking.

Alsop was born in 1947 and studied at the Architecture Association in London. He spent four formative years in the office of Cedric Price, the maverick modernist who believed architecture’s impact on the city also demanded impermanence; buildings could be bold, fleeting and constantly on the move. His own office was set up in the early 1980s with first John Lyall and then Störmer and in addition to Le Grand Bleu, other key buildings from this period include a ferry terminal in Hamburg and the copper-clad library in Peckham, south London, which won the Stirling Prize in 2000. Raised up on slender pilotis, the library was a breath of fresh air in a moribund domestic architecture scene. It pre-dated the obsession with grand ‘iconic’ statements yet acknowledged that one of its key roles was to be seen, not melt into the cityscape.

Pioneer Village, Toronto, Canada.

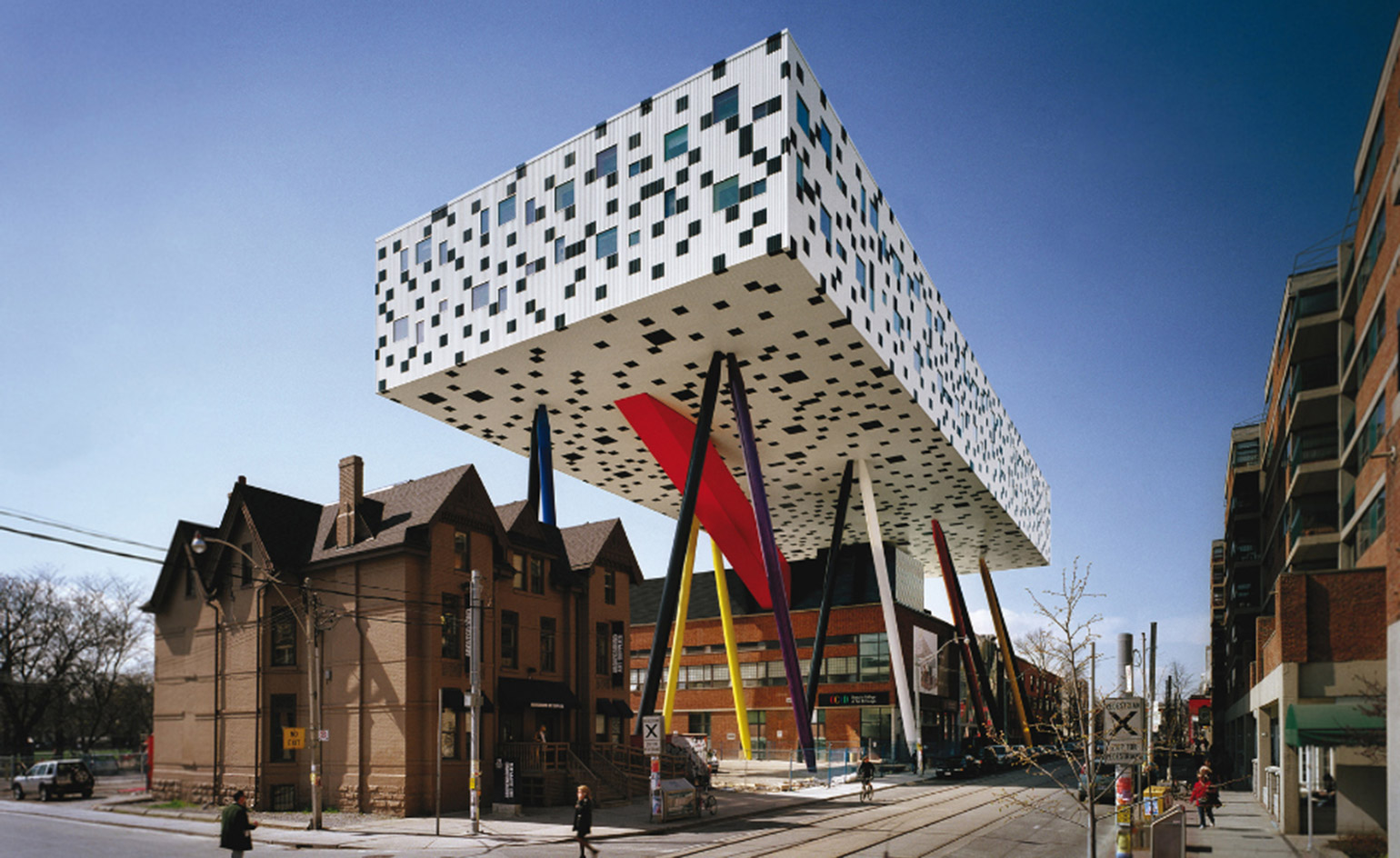

In 2000, Alsop went it alone. The Sharp Centre for Design in Ontario is effectively Peckham Mk2, a bigger, bolder, taller box with pixelated supergraphics. A couple of miles down the road in South London he also designed the Ben Pimlott Building at Goldsmiths, a raised studio building crowned with a tangled steel spaghetti sculpture. There were other major works, including the Palestra office building, the spectacular North Greenwich jubilee station (the debarkation point for the Greenwich Millennium Exhibition in 2000), and the ‘stacked chips’ flats in New Islington commissioned by Urban Splash. With ideas like ‘Supercity’, which expanded Price’s vision of a technotopian urban corridor across the centre of the country, Alsop briefly became a minor television star, scribbling artistically and speaking laconically about architecture’s regenerative power. He was ahead of his time in this respect.

By the end of the Noughties, the enfant terrible tag was starting to sag. Clients wanted bold, but his imagination rarely looked a budget in the eye, and grand plans and big schemes evaporated off the drawing boards. Alsop always combined architecture with art, painting big sploshy abstracts that mirrored his building’s grand sweeps of colour. His habit of heading off to the Med to paint (the results of which resulted in several monographs) didn’t help the bottom line and business missteps and increasingly cautious clients – not to mention a backlash against the ‘blob’ in the architectural press – saw Alsop marginalised. Eventually he relinquished his own practice to sit in as a named consultant for much larger, less forward-thinking firms.

Alsop’s vision worked well in London, a city that’s used to the rough and tumble of big ideas. Unsurprisingly, though, the latter stages of his career found him exploring the fast-moving world of Chinese urbanism, trying to bring his experience and vision of urbanism to a very different world. Alsop was a necessary and welcome foil to the sober steel machismo of high-tech design. He was an unabashed populist, undaunted by criticism, but nevertheless subject to the whims of fashion and taste. Alsop’s built legacy leaves many cities a much richer place.

Ontario College of Art & Design, Toronto by Alsop Architects (2004)

Peckham Library, London by Alsop and Stormer (2000).

Michael Faraday Community School, London by Alsop Sparch

Carnegie Pavilion, Headingly, Leeds, by Alsop sparch (2010)

Chips, Manchester by Alsop Architects (2009)

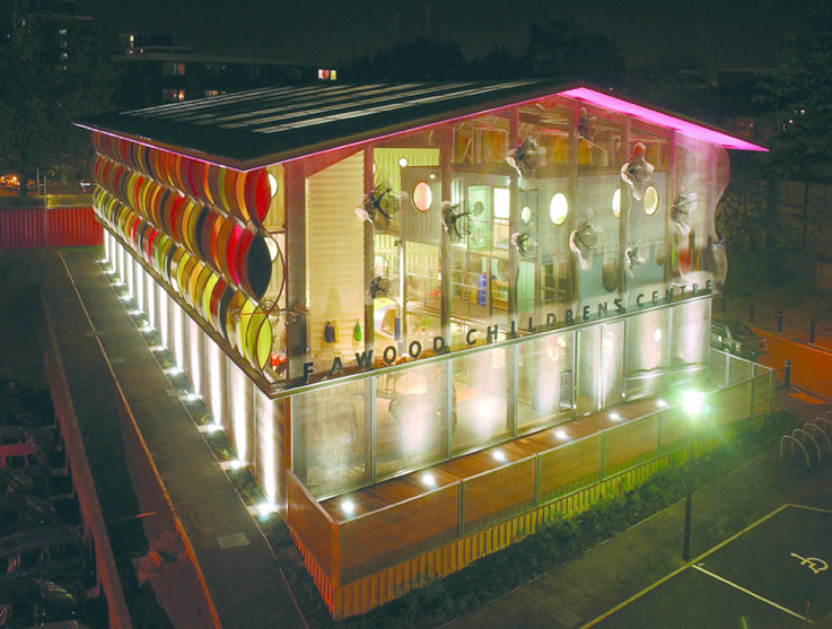

Fawood Children’s Centre, London by Alsop and Partners (2004)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.