Malta’s London Design Biennale installation ‘reclaims death as a moment of reflection, not fear’

Wallpaper* speaks with Andrew Borg Wirth, curator of Malta's installation, ‘URNA’, which reimagines cremation rituals

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

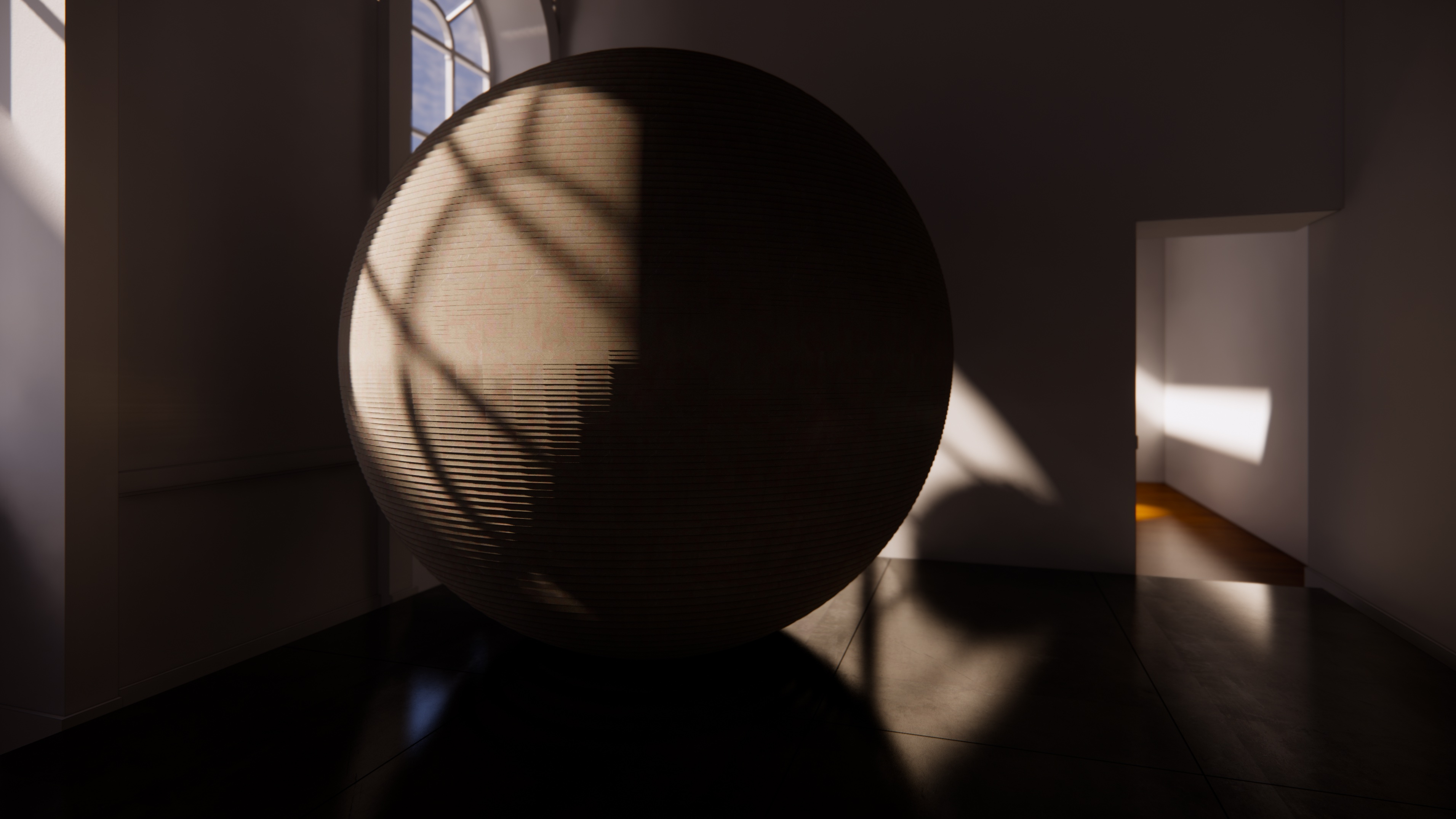

At Somerset House from 5 to 29 June 2025, the London Design Biennale 2025 explores the theme ‘Surface Reflections’ – a prompt to consider how identity, memory and ritual shape the landscapes we inhabit. Among the most quietly radical pavilions is Malta’s URNA, an architectural installation that contemplates death through design as imagined by a team of architects led by Anthony Bonnici, from Maltese firm Ebejer Bonnici. Reimagining cremation not as an isolated act of disappearance but as part of a communal, cosmological gesture, URNA offers a new material and spiritual vocabulary for memorialisation. A team of leading architects and designers, an art director, photographer, filmmaker and curator all come together in this united effort.

Malta’s relationship with stone is intimate and ancestral. From the pre-Neolithic megaliths of Ġgantija and Ħaġar Qim to catacombs and funerary urns, the island’s topography is one of sedimented memory. Recent archaeological discoveries, pushing the date of Malta’s earliest human presence further back than previously understood, serve only to deepen this connection – grounding the Maltese landscape as a site of ritual, continuity, and reverence.

'It’s difficult to grow up in Malta without these structures living inside you,' says Andrew Borg Wirth, URNA’s curator. 'We think of our ancestors and how they gave meaning to death. That relationship was tactile, cosmic, essential. URNA responds to that inheritance.'

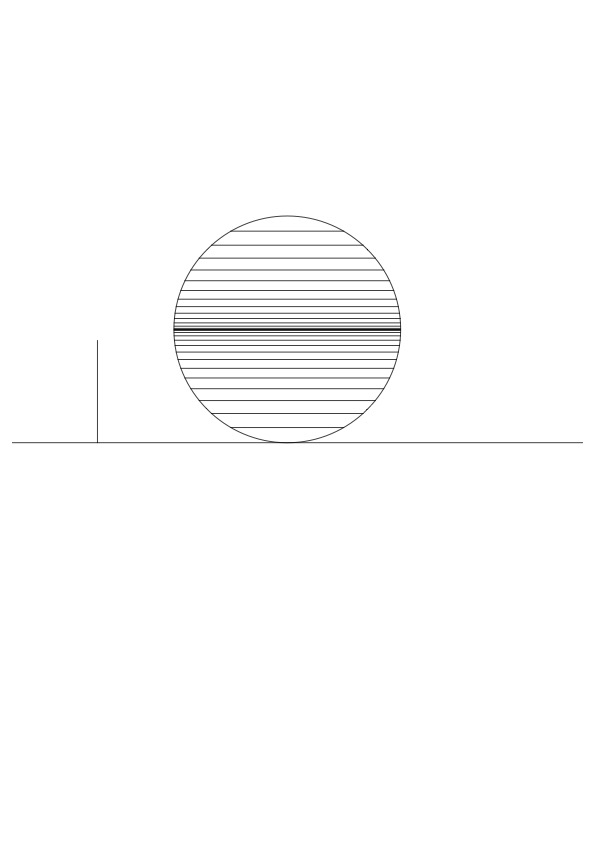

URNA draws from this heritage, not by replicating its forms, but by engaging with its philosophy. Rather than isolated tombs or individual graves, it presents a collective field of spherical stone urns, each subtly embedded with cremated remains. Set within a disused quarry in Malta and reimagined at Somerset House, URNA transforms body into landscape, dust into structure. 'Each unit is part of a larger whole,' Borg Wirth adds. 'Like stars in a galaxy.'

The arrival of URNA at the biennale coincides with a pivotal moment in Maltese cultural history. Only recently has legislation permitted cremation on the islands – a shift that opens space for public discourse around how death is handled in contemporary Maltese society.

'My thesis was a crematorium in Gozo,' Borg Wirth says. 'And now, with Malta embracing cremation, it felt urgent to propose a future for it. A radical one.'

In this way, URNA is not simply a speculative design project, but an active intervention – one that speaks to a broader conversation about death, sustainability, and the role of design in shaping ritual. Borg Wirth continues: 'Death is a core part of being human. But in many societies today, we’ve turned away from it – made it sterile, invisible. URNA reclaims death as a moment of reflection, not fear.'

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘Death is a core part of being human. But in many societies today, we’ve turned away from it – made it sterile, invisible. URNA reclaims death as a moment of reflection, not fear’

Andrew Borg Wirth

That reclamation is expressed materially. The spheres that make up the installation are composed of Recobel, a reconstituted Maltese limestone developed by Halmann Vella. The material is formed from dust – waste from the stone extraction process – making the urns both conceptually and ecologically circular.

'It’s an alchemic process,' Borg Wirth says. 'From waste and ruin, something new is cast.'

If URNA’s material origins are local, its ambitions are universal. In collaboration with students from the University of Malta and designers from across the Mediterranean and beyond, the team explored how this ritual might translate across different geographies. Proposals emerged for adaptations in Chicago, Johannesburg, Iceland and the Amazon – each rooted in local materials and context, yet unified by the shared gesture.

'Death is one of the last truly universal experiences,' Borg Wirth explains. 'We may grieve differently, but we all grieve. We wanted URNA to speak across cultures. It’s less a sculpture than a language.'

The result is striking in its restraint. The installation, which was designed by lead Architect Anthony Bonnici together with architects and designers Thomas Mifsud and Tanil Raif, resists the over-personalisation often associated with modern mourning. 'We’re pushing back against hyper-individualised memorials,' he continues. 'URNA is about connection. It invites a geography of remembrance – a sense of belonging not just to family, but to place, to earth, to each other.'

‘URNA is about connection. It invites a geography of remembrance – a sense of belonging not just to family, but to place, to earth, to each other'

Andrew Borg Wirth

This vision led by Art Director Matthew Attard Navarro, who runs London-based firm ANCC, is extended through a film by Stephanie Sant, photography by Anne Immelé, and a forthcoming multi-volume book series. The film, ethereal and mythic, imagines a ritual procession that blurs the lines between performance and ceremony, while Immelé’s images trace the textures of funerary landscapes, death masks, and quarry dust. Together, these mediums form a broader ecosystem of storytelling, anchoring URNA in both emotion and myth.

At Somerset House, URNA manifests as a large cast-stone sphere – a monumental memento mori, impossible to ignore. It is flanked by the film and selected ephemera that together offer a portal into a speculative future that feels deeply rooted in ancient truths. But URNA is not content to remain an exhibition. The team envisions its real-world application in Malta and beyond – not just as a memorial architecture, but as a new cultural tradition.

'As Malta navigates environmental and social change, we need design to lead with sensitivity,' says Borg Wirth. 'URNA is a gesture toward that – stillness amidst flux.'

The project has already sparked significant local dialogue, with support from Arts Council Malta, the Faculty for the Built Environment, and private industry. A public lecture series, educational workshops, and a planned documentary extend URNA’s reach beyond the walls of the Biennale, transforming it from concept to movement.

‘If this project can help others imagine a more beautiful way to say goodbye, then I think it’s done something important’

Andrew Borg Wirth

For the whole team, the experience has also been personal. 'URNA has deepened what we already believed – that death needs greater meaning in our lives. If this project can help others imagine a more beautiful way to say goodbye, then we believe it’s done something important.'

As the installation finds form within Somerset House and in Malta’s quarries, its real resonance lies in what it asks of its audience – to reconsider how we mourn, how we mark, and how we remember.

'In this ball of stone,' Borg Wirth says, 'as someone passes their hand across a single sphere in a tapestry of many, I hope they feel something. That it’s beautiful that we die. Because if nothing ended, nothing could begin.'

With URNA, Malta offers a design that is not just for the eyes, but for the soul – a contemplative object that stands as a poetic response to a universal truth: that from ashes, art may yet rise.

Project team:

Andrew Borg Wirth, Curator/Architect

Anthony Bonnici, Architect/Designer

Tanil Raif, Architect/Designer

Thomas Mifsud, Architect/Designer

Matthew Attard Navarro, Art Director

Anne Immelé, Photographer

Stephanie Sant, Filmmaker

londondesignbiennale.com