Venice Biennale 2017: the top ten pavilions, from colossal sculptures to dystopian visions

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

There is no escaping life’s big themes – the migration crisis, identity politics, populism, an uncertain future – at this year’s Venice Biennale. This, the 57th edition, is curated by the Pompidou Centre’s Christine Macel, under the title ‘Long Live Art’, and most countries have used their pavilions to remind us that the world needs our urgent attention. Antigua and Barbuda, Kiribati, and Nigeria are taking part for the first time bringing a total of 86 nations to the Giardini, the Arsenale and many of Venice’s finest palazzos, churches and galleries.

In the US pavilion, American artist Mark Bradford examines ‘the collapse of the centre’, while Australian artist Tracey Moffatt represents her country with photographs and film referencing migration and false history. A small, Russia-funded Syrian space on the island of Guidecca pays homage to the destroyed city of Palmyra. At the French pavilion, Xavier Veilhan’s live sound experiment hit all the high notes.

Read more about Xavier Veilhan’s live sound experiment at the French pavilion

Other nations, though, have gone for a lighter touch. At the Finnish pavilion, two messianic figures, represented by talking animatronic puppets, visit the Finland they created millions of years earlier, and try to make sense of contemporary culture there. They, and their ‘findings’ are the work of artists Nathaniel Mellors and Erkka Nissinen. On Guidecca, the Icelandic pavilion is the final destination of Ūgh and Bõögâr, a pair of 36m tall trolls who journeyed from the Berlin studio of artist Egill Sæbjörnsson to Venice creating music, art, perfume and fashion along the way.

Equally eccentric are the outfits of many a biennale visitor, and offbeat performances pop up all over the city just when you’re least expecting them. Enter the mute and miserable man, who stood for hours near the tied-up mega yachts holding a tray of ice with a dead fish at his feet. What he symbolised was hard to fathom, but trying to decipher such seemingly random acts is part of the fun of the Venice Biennale.

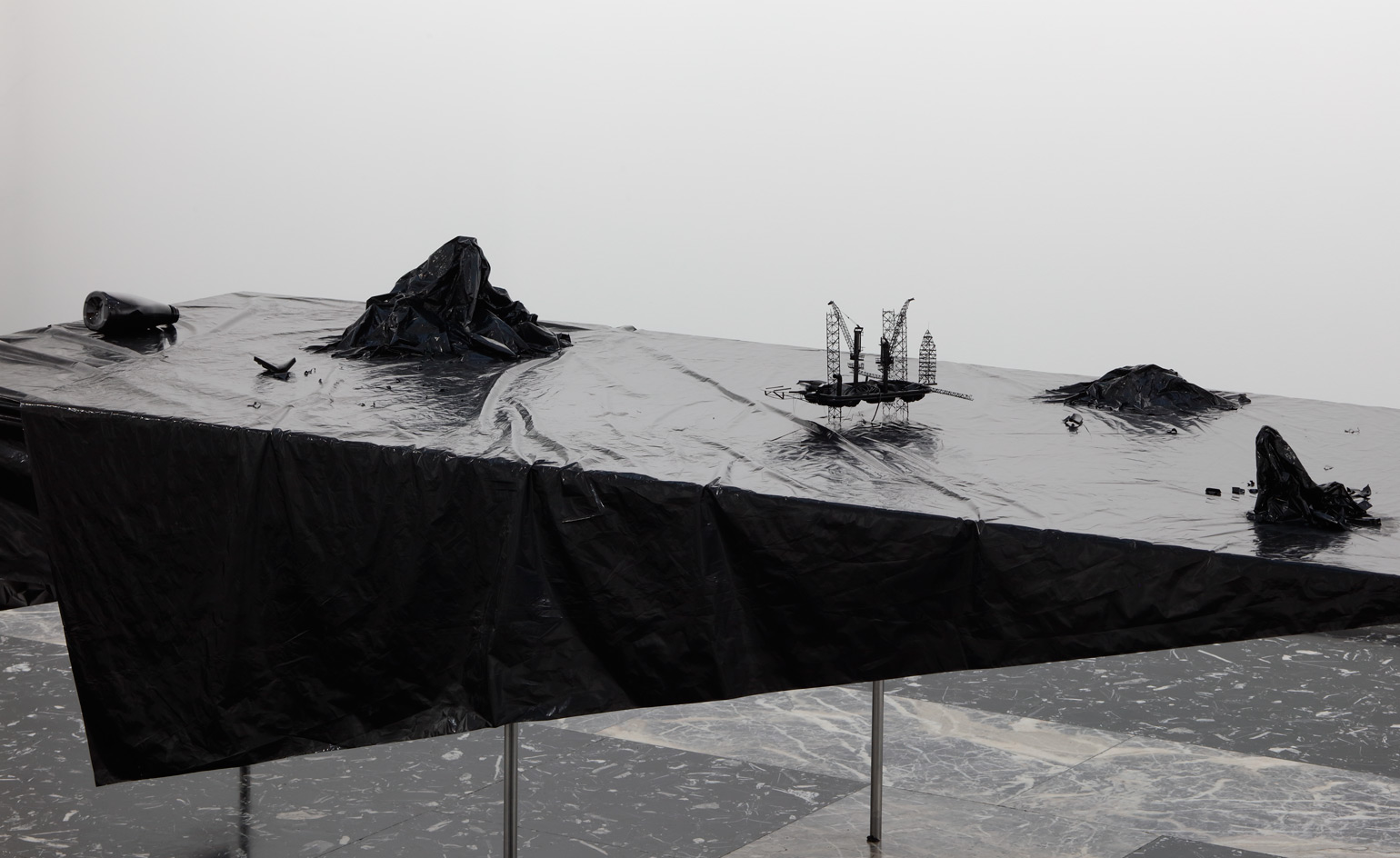

Israel: Tel Aviv artist Gal Weinstein uses metallic wool, unravelled felt, pillow stuffing and mould to create sculptures and installations underpinned by historical and geographical references that lead to a post-apocalyptic scene

Israel: Weinstein also sees his project as a melancholic and poetic allegory of the Israeli story – one composed of miraculous acts and moments of enlightenment as well as neglect and destruction

Egypt: Cairo-based artist Moataz Nasr has transformed the entrance to the Egyptian pavilion into a mud hut. Inside a film recounts a story of a small fictional village and the myths and fears that preoccupy the villagers

Egypt: It’s one of many works by Nasr to explore the tensions between tradition and globalism and their impact on social development

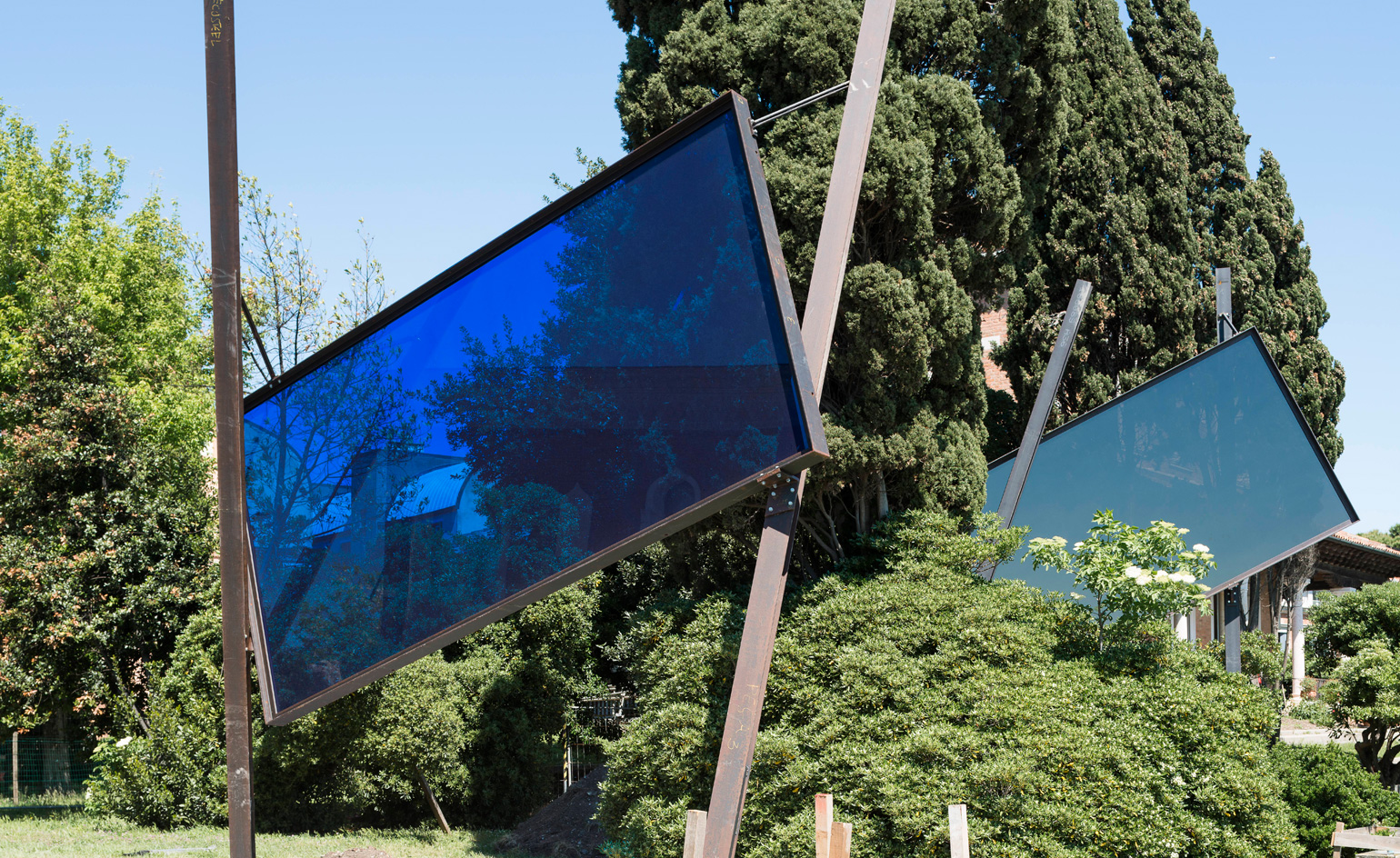

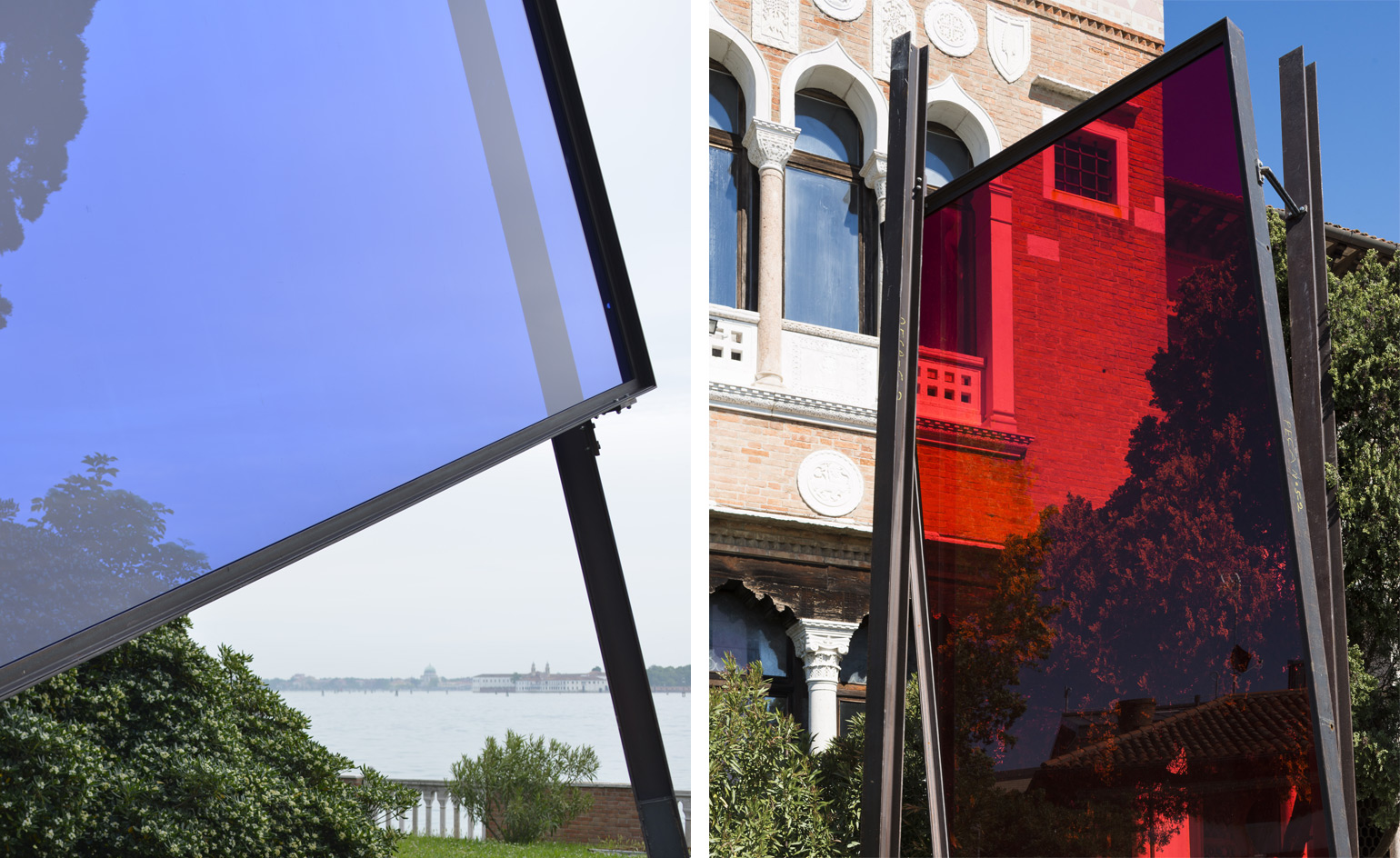

Portugal: Six giant glass panels are dotted around the gardens of Villa Hériot which doubles as the Portuguese pavilion. They are the work of Portuguese artist José Pedro Croft and bring a touch of modernity to this secluded corner of Guidecca

Portugal: Built in 1929 for a French merchant, it is a paradise of architectural detailing and serenity, and viewed through Croft’s colourful panels the site takes on a different hue. It’s worth taking a peek next door, at last year’s biennale exhibition, the Campo di Marte housing scheme by Alvaro Siza

Great Britain: Daunted by the prospect of representing the UK, it was not until artist Phyllida Barlow saw the biennale as ‘a huge group show that reflects the state of the world’ that she was able to do the job. And she has done it with gusto.

Great Britain: Every part of the British pavilion has been colonised by her colossal sculptures in timber, fabric, concrete and found materials, and so closely packed are they that you can get right up close in a way that a gallery rarely permits

Korea: Tacky neon advertising motifs reminiscent of Las Vegas and Macau’s ‘casino capitalism’ decorate the exterior of the Korean pavilion. They are the work of Seoul-based artist Cody Choi (pictured, Venetian Rhapsody – The Power of Bluff, 2016-17) who shares the pavilion with fellow Korean Lee Wan.

Korea: Both artists evaluate life in Asia under capitalism, and Wan’s vast display of clocks records the number of hours people in various parts of the world have to labour to afford a meal. Pictured, Proper Time: Though the Dreams Revolve with the Moon, and For a Better Tomorrow, 2017, both by Lee Wan.

Germany: Penned up Dobermans, haunting melodies, and gaunt, tattooed dancers were par for the course during Faust, a five-hour performance at the German pavilion. Courtesy of the German Pavilion and the artist. Emma Daniel and Lea Welsch in Faust, 2017

Germany: Adidas-clad figures crouched, dead-eyed on wall-mounted plinths and crawled under a glass floor in a subterranean world that felt part prison, part asylum. Courtesy of the German Pavilion and the artist. Franziska Aigner and Eliza Douglas in Faust, 2017

Germany: German artist Anne Imhof won the Golden Lion for Best National Participation for her dystopian vision in what was the most talked-about pavilion of the biennale. Courtesy of the German Pavilion and the artist. Franziska Aigner and Eliza Douglas in Faust, 2017

Japan: The heads of visitors poking unwittingly through a hole in the floor of the Japanese pavilion makes for entertainment enough. That they are part of an installation featuring discarded clothing whose threads have been woven into roller coasters, railway tracks and towers, is even more intriguing. Pictured, installation view of Turned Upside Down, It’s a Forest.

Japan: Architectural and industrial structures inspire artist Takahiro Iwasaki and alongside his drawings and models, the pavilion is filled with intricately carved wooden sculptures that are reflections and motifs of famous temples and shrines. Pictured, Out of Disorder (Turned Upside Down, It’s a Forest), 2017.

Tunisia: For its first appearance at the biennale since 1958, the Tunisians have set up two ‘checkpoints’ across the city along with a central issuing centre in the Sale d’Armi building in the Arsenale

Tunisia: Manned by genuine migrants (who have been granted 60-day visas, board, lodging and a wage by curator Lina Lazaar) each checkpoint grants a ‘travel document’ to anyone wanting one. Designed by the company that makes Schengen visas, they resemble real passports and require only a thumbprint for validation

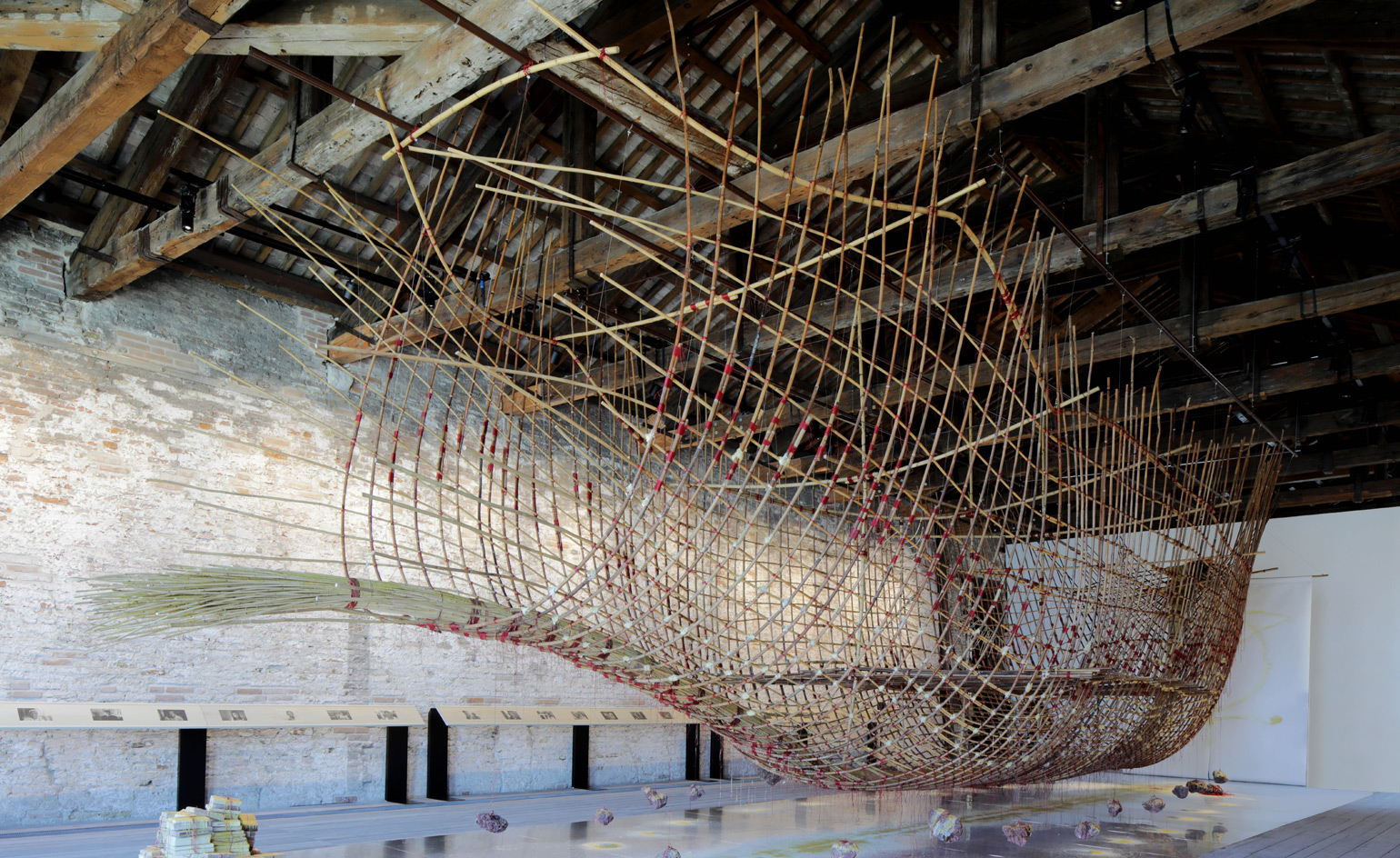

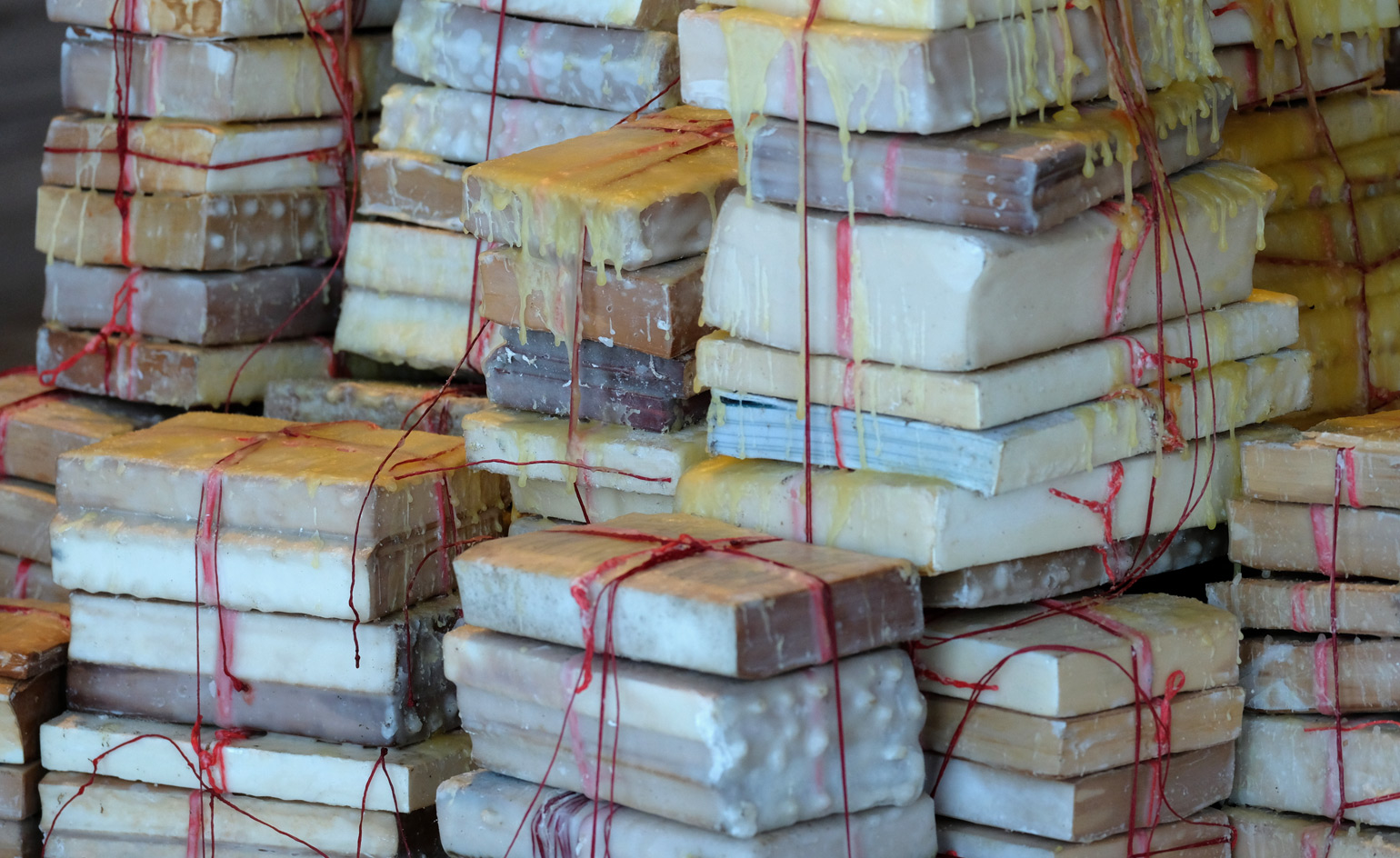

Singapore: It took Singaporean artist Zai Kuning three weeks on site in the Arsenale to construct his 17m long sailing ship. Made from rattan, string and beeswax, it’s the fifth such vessel created by Zai, who has spent years focusing on the seafaring peoples who occupied the South Seas before the lands were separated by politics. Pictured, Dapunta Hyang Transmission of Knowledge, 2017

Singapore: His artworks refer to ancient Malay kings, lost trading cities, customs, rituals and threatened communities, among them the orang laut, believed to be the first people of Singapore

Georgia: Tbilisi-born artist Vajiko Chachkhiani has reassembled an abandoned wooden house, which he found in the Georgian countryside, in the Arsenale. He has filled it with typically rustic furniture and a few simple objects.

Georgia: It’s the real thing in every way, apart from the permanent rainstorm beating down inside. Water crashes upon its walls floor and furniture for the duration of the biennale, and visitors can witness its transformation from quaint rural dwelling to moss covered shell.

INFORMATION

The 57th Venice Biennale continues until 26 November. For more information, visit the website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Emma O'Kelly is a freelance journalist and author based in London. Her books include Sauna: The Power of Deep Heat and she is currently working on a UK guide to wild saunas, due to be published in 2025.