teamLab: how a Tokyo art collective pioneered an immersive art boom

With an operatic intervention and a show at Pace Geneva, teamLab, the now-700-strong Tokyo-based collective that blazed a trail for experiential, tech-fuelled art, continues to value ‘physical interaction in physical space’

Over the last decade, Tokyo-based techno-creative collective teamLab has proved the crowd-pleasing (albeit not always critic-pleasing) potential of the ‘immersive’, interactive art (is it strictly art?) installation.

Established by Toshiyuki Inoko in 2001, the collective gained an international reputation when Takashi Murakami showed its work at his Taipei gallery in 2011. Since then, teamLab has created spectacle and wonder – often involving light and lasers or interactive digital simulacra of the natural world and the apparent dissolution of physical space – pretty much everywhere. It now has permanent exhibition spaces in Tokyo, Shanghai, Singapore and Macau with more to follow. (Tokyo’s teamLab Borderless opened in 2018 and attracted 2.3 million visitors in its first year, making it the most popular single-artist museum in the world.)

Lasers at Opera Turandot, Grand Théâtre de Genève

Of course, teamLab is no longer the only player in the immersive installation space. Other artists, designers, galleries, and cultural institutions have noted that pulling power. (Signed by Pace gallery in 2014, teamLab also pioneered a new economic model for artists and art collectives. Much to Pace’s initial scepticism, teamLab insisted on charging for tickets to its 2017 exhibition at a pop-up Menlo Park space, a former Tesla showroom, in Silicon Valley. Charging for admission is what museums, not private galleries do. But teamLab’s work is not private-collector friendly so, it argued, ticketing was the only way to fund the works. The show proved a huge success and revenue generator. Pace, in turn, launched Superblue, its dedicated experiential art division in 2020 with a permanent space, for ticketed shows, in Miami and a new outpost set to open in Kyoto).

Dress rehearsal at Opera Turandot, Grand Théâtre de Genève

The trick for teamLab – now an almost 700-strong super studio or ‘art stack’ – is maintaining some kind of creative distance from other digital art makers. Its collaboration on a new production of Puccini's Turandot, at Geneva's Grand Theatre 24 June – 3 July 2022, is evidence of that creative stretch.

The production is directed by Daniel Kramer, former artistic director of the English National Opera, and known for his radical updates of opera's canonical texts, including a collaboration with Anish Kapoor on a production of Wagner's Tristan and Isolde (and a hugely ambitious, non-canonical and financially catastrophic version of King Kong).

Lasers at Opera Turandot, Grand Théâtre de Genève

Kramer’s new Turandot is similarly iconoclastic. The story of a prized princess testing a stream of suitors is reimagined as a dystopian game show (for the record, the production has been in the works for four years, plotted before Squid Game made dystopian game shows a thing. It is, though, similarly gruesome. One of Kramer’s innovations is that ‘contestants’ who fail Turandot’s tests are not beheaded, as is their traditional fate, but well and truly emasculated).

Kramer met up with Inoko in 2017 to talk about how he might incorporate teamLab’s light and lasers into a new work before signing them up to work on Turandot. Adam Booth, the collective’s art director on the project, admits that it has involved a certain amount of creative negotiation. ‘He came to see us in Tokyo and there was some intense brainstorming, working out how we could participate and keep our own aesthetics and integrity. Daniel had his ideas and we had ours and we worked through that. It was a long process.’ And got longer. Given that productions of Turandot usually feature a 100-strong chorus on stage, a Covid-safe outing was out of the question.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Dress rehearsal at Opera Turandot, Grand Théâtre de Genève

Despite the game show conceit, Booth insists teamLab was not enlisted to provide an easy spectacle. ‘When you say lasers, most people think of light shows and green beams but it’s not about that for us. We’re trying to make planes of light and three-dimensional shapes by overlapping different planes and creating moiré effects when the lights cross. It’s not a pop concert, we’re using them to express something very subtle and delicate.’

The Covid hiatus gave Booth and his team time to work out how they could create a fluid architecture, unbounded by the proscenium arch, in lights and lasers. The studio’s in-house architecture team, teamLab Architects, meanwhile, were drafted to work on scenography, creating a stark, rotating multi-level structure, the gender power hierarchy at work in the play – with Princess Turandot very much on top – made physical. Booth and his team use mirrors and LEDs inside the set to create an intense kaleidoscopic take on the unfolding psychic drama.

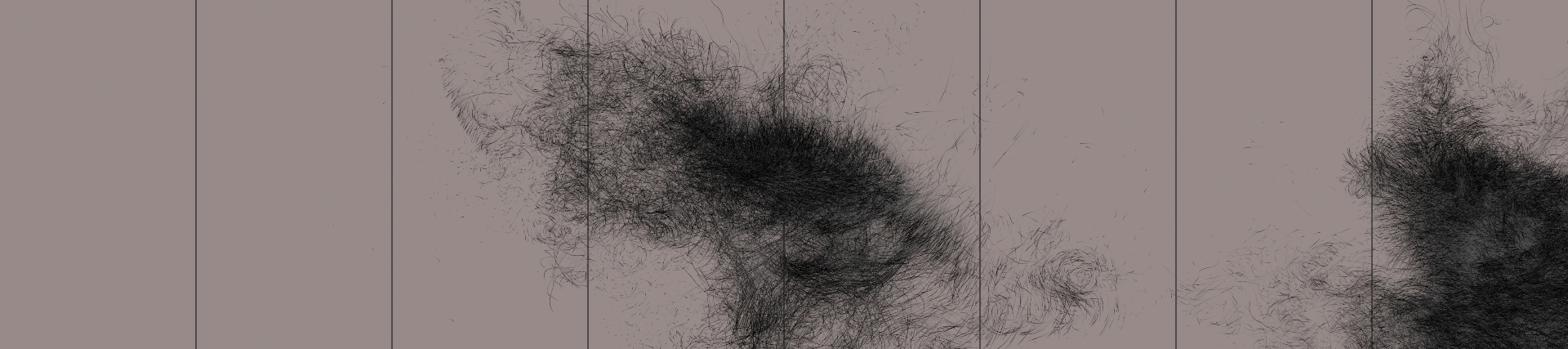

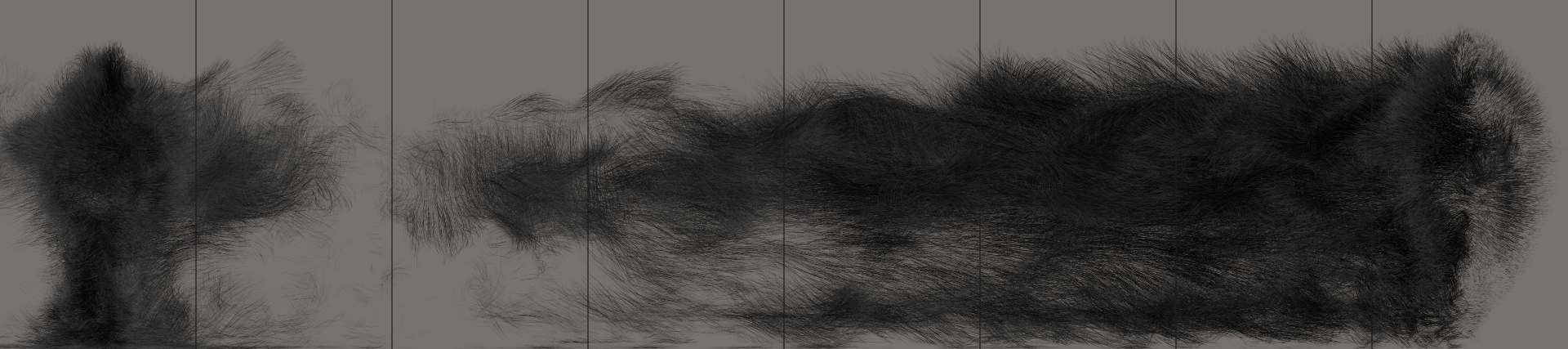

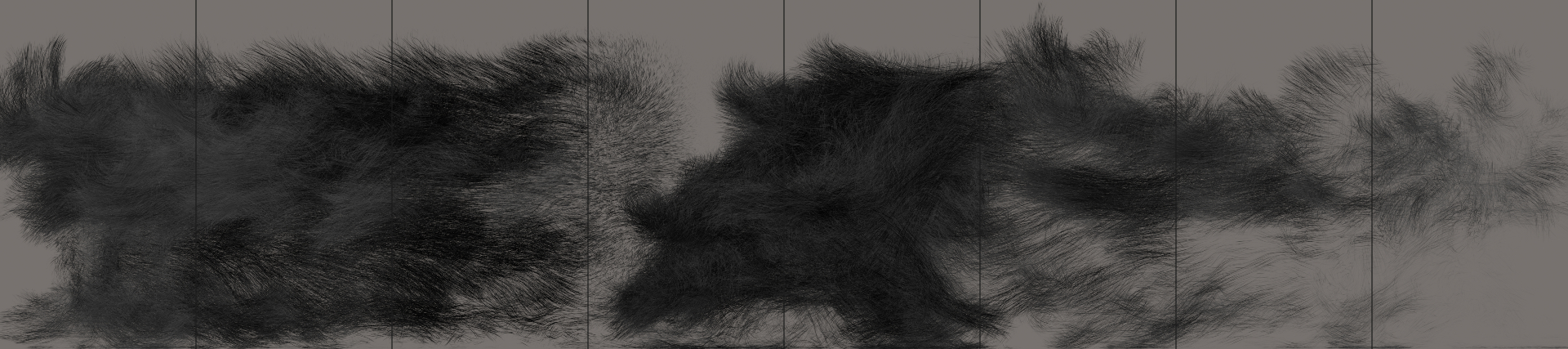

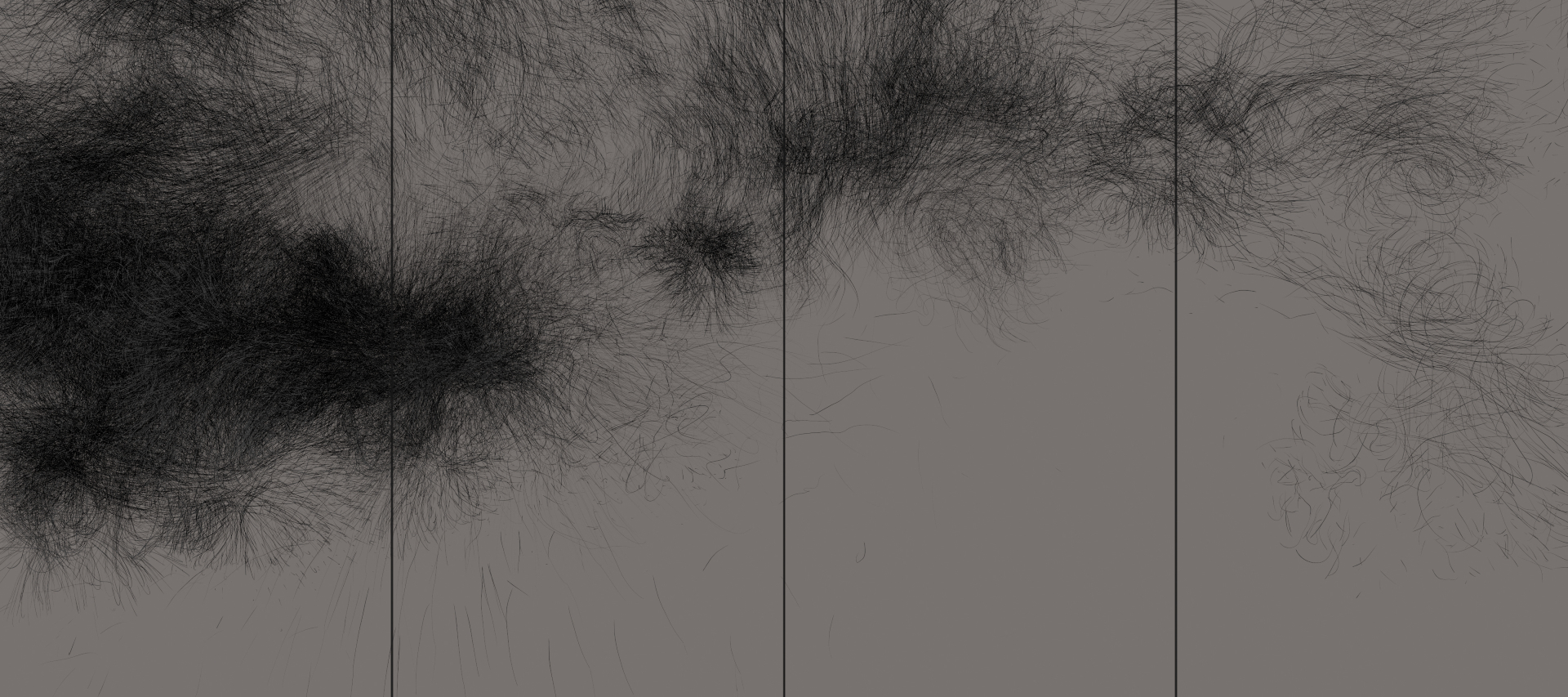

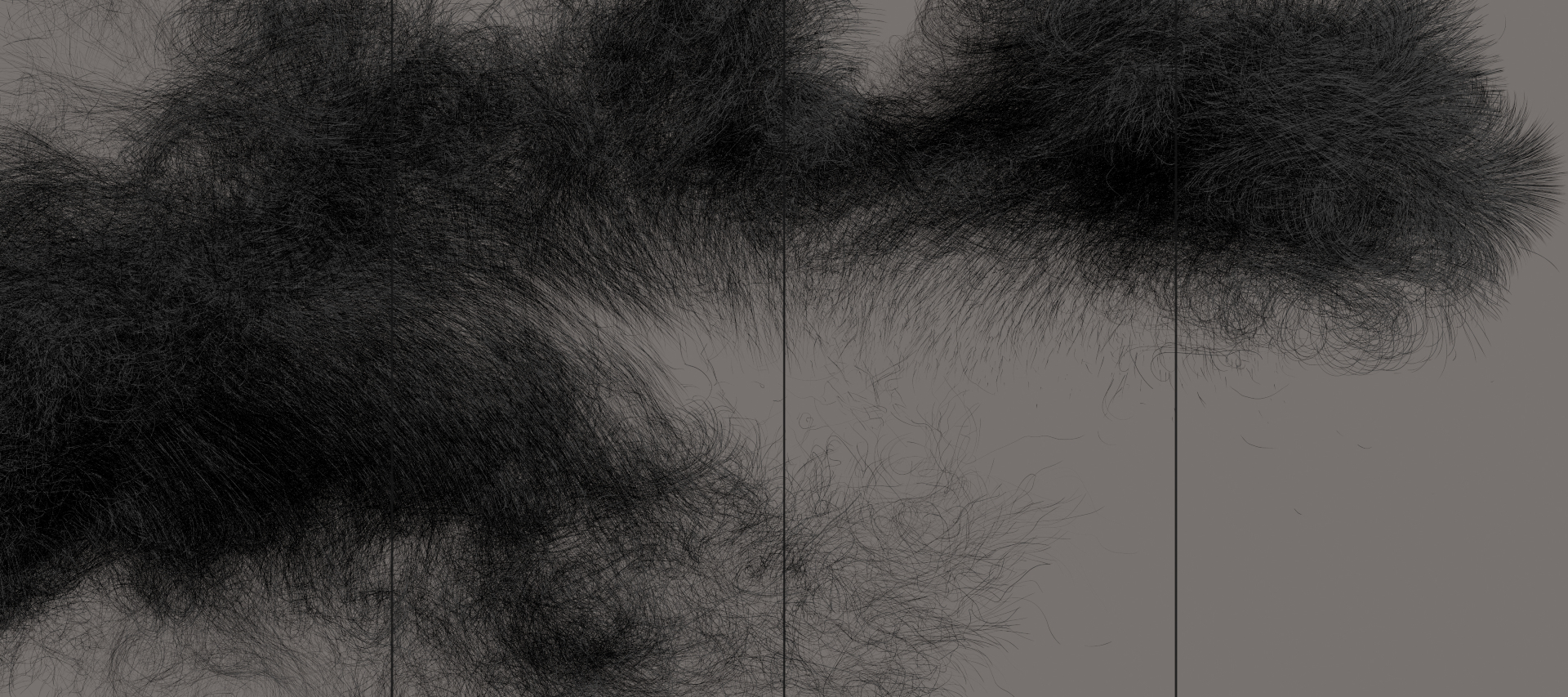

Dissipative Figures – 1000 Birds (stills), teamLab, 2022. Digital Work, 8 channels, Continuous loop

They also worked with the legendary costume designer Kimie Nakano. ‘Daniel is this amazing, energetic character and he wants everybody on board with everything. And it created this really interesting mix,’ Booth says.

The Grand Theatre is also planning to screen the production for free, live in Geneva’s Parc des Eaux-Vives. Though he admires the democratising impulse, Booth says a lot of the power of teamLab’s work will be lost in translation. ‘Lasers are just not suited to being filmed.’

For all the high-tech wizardry involved, what teamLab does is meant to be experienced physically, in person, and preferably collectively. It’s a point picked up by the collective’s project manager Kazumasa Nonaka.

teamLab, Dissipative Figures – Human (still), 2022, Digital Work, Single channel, Continuous loop

Nonaka is behind another, unrelated, Geneva outing for the collective. Opened earlier this month at Pace’s outpost in the city, ‘Existence in an Infinite Continuity’ is another series of installation pieces involving moving digital forms. These new works, though, have a rare, raw spareness. A number of works called Dissipative Figures use minute lines to map the movement of air around human bodies and birds in motion. They are simple but mesmeric and hauntingly beautiful renderings of the disturbed, energised air we leave in our wake.

‘As an expression, it’s very quiet but what’s happening is very dynamic; you see lines almost exploding as the figures run or walk,’ Nonaka says. ‘We are known for these very saturated and dynamic colours but just the difference in thickness and direction of these black and grey lines was enough to show the three-dimensionality of the air that moves around the human body.’ And if they feel a little sketchy, in a good way, that’s because they are just the first take on what Nonaka says will be on an ongoing series.

teamLab, Dissipative Figures – 2 Humans (stills), 2022. Digital Work, 8 channels, Continuous loop.

Clearly, technology has advanced remarkably in the 20 years since teamLab was founded, or even over the last decade, when it has been a real international force. But Nonaka says that technology has only really helped speed up the collective’s creative and production process rather than effect any fundamental changes in the nature of its work. Advances in sensor technology have changed the degree to which its installations can be interactive (‘Existence in Infinite Continuity’ is also rare in that it is not interactive) and for how many people at the same time.

As for all artists and galleries, pandemic-induced shutdowns forced teamLab to look at how it might put work out on social media and digital platforms such as YouTube. The collective created a ‘participatory’ piece, Flowers Bombing Home, for YouTube but Nonaka admits it wasn’t hugely successful. And, he says, teamLab is taking a cautious wait-and-see approach to AR/VR and the metaverse. ‘We still believe in physical interaction in physical space.’

teamLab, Dissipative Figures – 1000 Birds (stills), 2022, Digital Work, 4 channels, Continuous loop

INFORMATION

teamlab.art

Turandot is at Grand Théâtre de Genève, 20 June - 3 July gtg.ch

Existence in an Infinite Continuity is at Pace Gallery, Geneva until 2 July pacegallery.com