How to conquer the Atomic City: the story behind U2 at the new Las Vegas Sphere

U2:UV Achtung Baby Live At Sphere redefines the 21st-century rock concert. We spoke to the band and its team about the genesis of this expansive art and music experience that marks the opening of the high-tech venue

Las Vegas wants to reclaim its title as the heavyweight entertainment capital of the planet. In the ring is the Sphere (officially known as The Sphere at The Venetian Resort), a $2.3 billion venue developed by the Madison Square Garden Sports Corp. Capable of housing 18,600 people, the structure was designed by Populous Architects and is envisaged as the first of a series of new generation venues to be built around the world (the second, planned for London’s Stratford, is currently on hold).

An early rendering of the Sphere

Over a five-year development process, MSG Sports’ team has hunted far and wide for content creators that can showcase the Sphere’s audio-visual scale and quality. The job of inaugurating this technical wonder has been taken up by U2, the Irish band with unrivalled experience of elaborate staging to accompany their epic soundscapes. Willie Williams, a longtime U2 collaborator, was tasked with shaping the show, U2:UV Achtung Baby Live At Sphere, which will run 29 September – 16 December 2023 (read our U2 in Las Vegas review).

The making of U2:UV Achtung Baby Live At Sphere

A cross-section render of the Sphere

‘Nothing like this has ever existed before,’ Williams tells us from the midst of last-minute preparations for the opening night. ‘It’s the confluence of art, science and diplomacy,’ he adds, hinting at the huge number of moving parts – both human and mechanical – needed to get the event off the ground.

For Williams, massive complexity has been a large part of his professional life. The first U2 show he worked on was the ‘War’ tour in 1983, and since then he has overseen 11 major global tours, pioneering many aspects of the modern stadium spectacle along the way, from the brooding atmospherics of the original Joshua Tree tour in 1987 through to the eerily prescient collision of imagery that served as the backdrop to the Zoo TV Tour, which wended its way around the world from 1992 to 1993.

The scale of the Sphere is hard to fathom

‘I won’t lie to you,’ the designer admits, ‘I wasn’t enthusiastic initially when the premise came up.’ The opportunity arose when Bono heard advance word of the Sphere’s construction and the potential for a set shaped around Achtung Baby’s 30th anniversary coalesced with the idea of not taking a huge and complex machine out on the road in the post-Covid era. Nevertheless, the U2 team has been up against the building’s stalled completion programme, as well as the need for the space to accommodate the other premiere attraction, Darren Aronofsky’s immersive cinematic experience Postcard From Earth, which opens on 6 October. Everything about the show started from an unknown.

The LED screen is the world's largest

This was a perfect match for the band’s finely honed ethos. ‘The technology has ebbed and flowed over the years,’ Williams says, ‘but U2’s vision has always been about pioneering – occupying space that no one else has thought of.’ It has been a long road to the stage of the Sphere, a journey not without its creative difficulties. ‘It wasn’t until around February that Edge said we’d cracked the code,’ recalls Williams, as the creative team initially struggled with a space that was both a constraint – no corners – and also a literal blank canvas.

The stage is a scaled-up version of Brian Eno's 'Turntable', itself a Wallpaper* Design Award winner

Characterised by a 90m tall circular exterior, covered in an LED screen, the Sphere contains a steeply raked auditorium, with the focal stage enveloped with a wraparound screen. Billed as the largest LED screen in the world, it comprises 268,435,456 pixels, the equivalent of 72 HD televisions. As the press pack points out, ‘every minute of content produced for Sphere is the equivalent of one hour of streaming television’.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘The quantity of data is mind-boggling,’ Williams confirms. ‘It means we’re effectively working at a 12K screen resolution (the Aronofsky film is at 16K), and each single frame of animation took around 15 minutes to render.’ It’s a far cry from the world of 1997’s PopMart, when Williams and his team oversaw the world's then-largest LED screen, a 50m structure that stretched the full width of the stage.

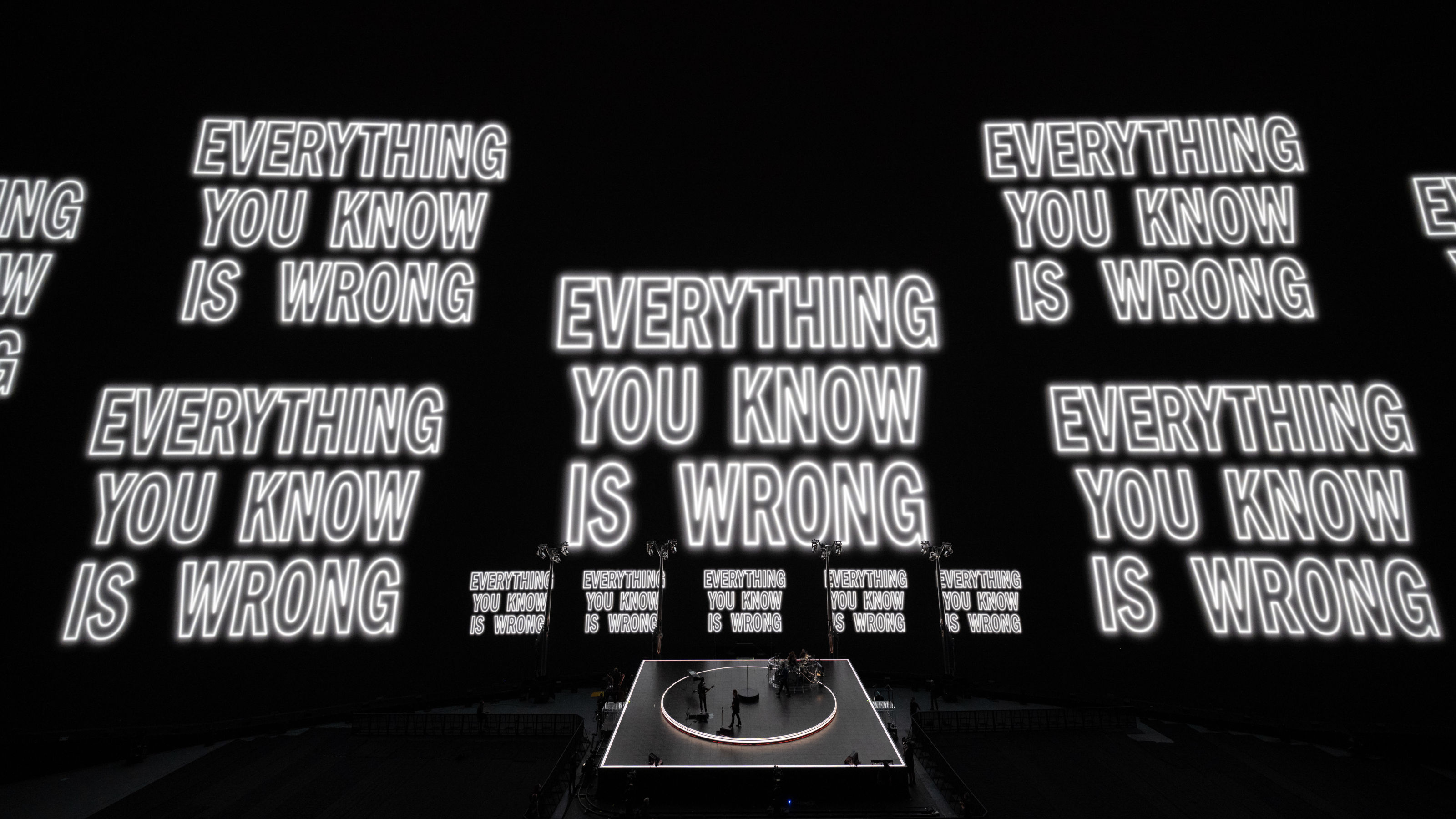

Elements of the show draw on 1992's Zoo TV Tour

Throughout U2’s performance history, screens have been both backdrop and structure, a three-dimensional canvas through which the audience experiences the music and imagery. Over the years, that imagery has been conjured up by a number of significant creative collaborators, including Brian Eno, Kevin Godley and Anton Corbijn. There was also a long-running partnership with the late architect Mark Fisher, who gave shape, structure and colour to these multimedia spectaculars, and whose company, Stufish (behind ABBA Arena), continues to play a major role. Starting with the Experience + Innocence Tour in 2015, the artist and stage designer Es Devlin has also been a key player in U2's creative arsenal.

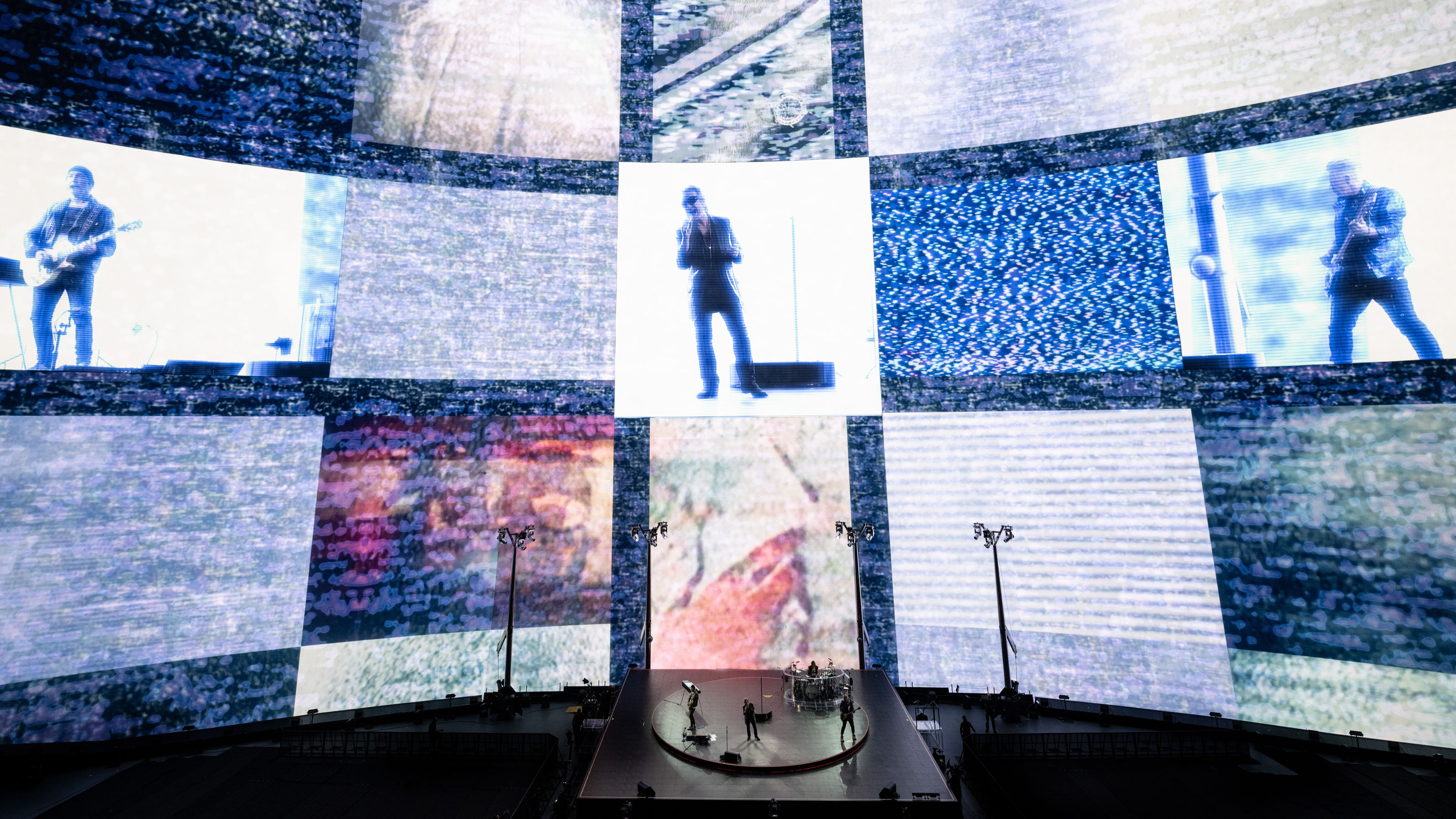

U2:UV Achtung Baby Live At Sphere is a dense visual collage

For U2:UV, Achtung Baby Live at Sphere, the roster expanded still further, with a section overseen by the masters of cinematic illusion, Industrial Light and Magic. There’s also input from Eno, once again, along with installations by video artists Marco Brambilla and John Gerrard and a specially commissioned piece by Devlin. The starting point for the show is the 1991 album. ‘With [2017’s] Joshua Tree Tour, I was very surprised they wanted to do an album-based show,’ Williams recalls, ‘but the band looked at it as if it was an all-new album, while Anton made all the films. There was absolutely nothing nostalgic about it.’

Imagery from Marco Brambilla's 'King Size'

A similar approach has been taken in Las Vegas. Achtung Baby has aged well. Marking the end of the band’s rootsy, rock’n’roll imperialism phase, it dived into new technologies, both sonically and visually, helping define the first decade of full-on media overload and global disruption – the fall of the Berlin Wall, the first Gulf War, the rise of the information age.

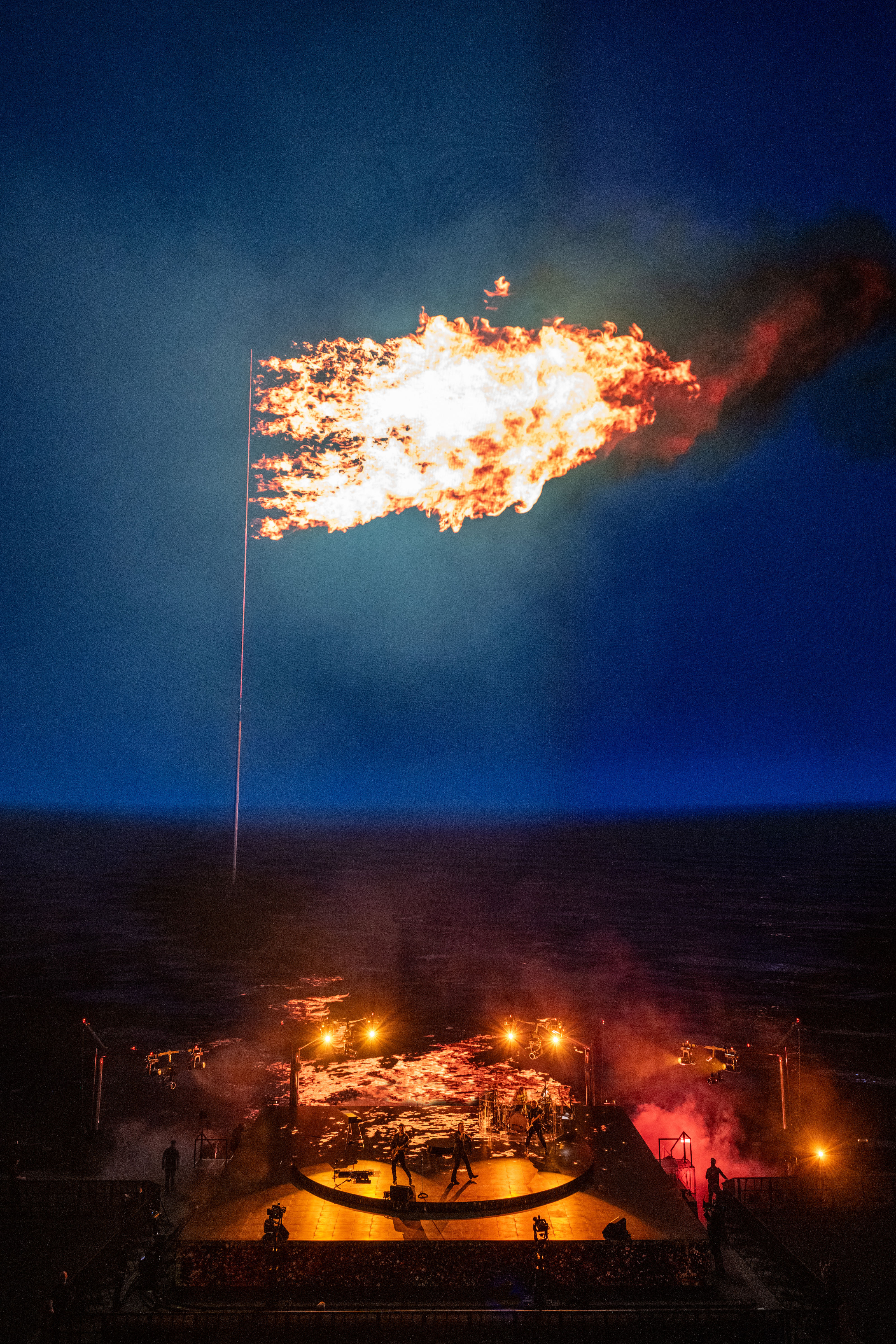

John Gerrard's 'Flag' series features prominently throughout the show

The accompanying tour, Zoo TV, with its suspended Trabants and scattered screens showing live and pre-recorded footage, was a deliberate bombardment of imagery, created in collaboration with Eno, artists Mark Pellington and Catherine Owens and others. Some of that unique imagery will resurface. ‘Initially, I didn’t think we’d revisit the Zoo TV era, because in the past 30 years, the entire world has gone that way,’ says Williams, ‘but the visual language still felt thrilling and fresh.’

Hyper-dense imagery for the modern era

Even working with the new sound system required a departure from convention. Built by German AV specialist Holoplot (who also worked on David Hockney’s Lightroom installation in London), the system consists of a vast matrix of speakers – 167,000 in total – seamlessly integrated behind the screen. ‘Even when Bono is talking from the stage it feels very conversational,’ Williams says, ‘it’s a very different sonic experience, very precise.’

U2’s longstanding sound designer Joe O’Herlihy has been closely involved with translating the ‘sonically dense’ Achtung Baby mixes into this new audio environment. Even producer Steve Lillywhite, a longtime U2 collaborator, was on board to advise. ‘An early decision that I made that really saved me was to bring everybody here,’ Williams says, pointing out that practically his entire team temporarily relocated to Las Vegas.

Marco Brambilla's 'King Size', a skewed homage to Elvis

The show is broken into three parts, starting with Achtung Baby, then on to songs taken from this year’s Songs of Surrender album, which features revisited and reworked tracks from the band’s copious discography. For this section, the physical stage setting comes into itself. A scaled-up version of Brian Eno’s Turntable, a fully-function deck originally shown at Paul Stolper Gallery in London, it promises a unique light show. ‘It almost started as a joke, but we quickly realised it would be brilliant,’ says Williams. Just like the original, the stage Turntable cycles through an ever-changing series of ‘colourscapes’, generated by an algorithm.

Marco Brambilla's 'King Size'

The final section dips into the most richly anthemic seam of U2’s back catalogue. ‘Es has made a couple of wonderful pieces to close the show, and there’s work by John Gerrard and ILM as well,’ he says. ‘The building is a canvas we’ve been given, so we have to use it. So we don’t just deliver fireworks, we blow up the whole building.’ In this section, the full cinematic potential of the Sphere is unleashed. ‘It would be rude not to,’ Williams concedes. ‘Although simple graphics work really well, you can completely shapeshift the room.’

John Gerrard, 'Surrender'

For the band themselves, this run of shows offered an opportunity to broaden and strengthen long-running creative partnerships. ‘We were looking around for a way of memorialising and celebrating Achtung Baby,’ says Adam Clayton, who started U2 with schoolfriends Paul Hewson (aka Bono), David Evans (the Edge), and Larry Mullen Jr in 1976. ‘Zoo TV had predated reality TV, fake news, social media – all these things. Bono had heard about this new venue in Vegas with nearly 20,000 seats, custom sound and an incredible screen that was akin to the whole audience having a VR experience. In the post-Covid era, it was appealing not to have to travel every night.’

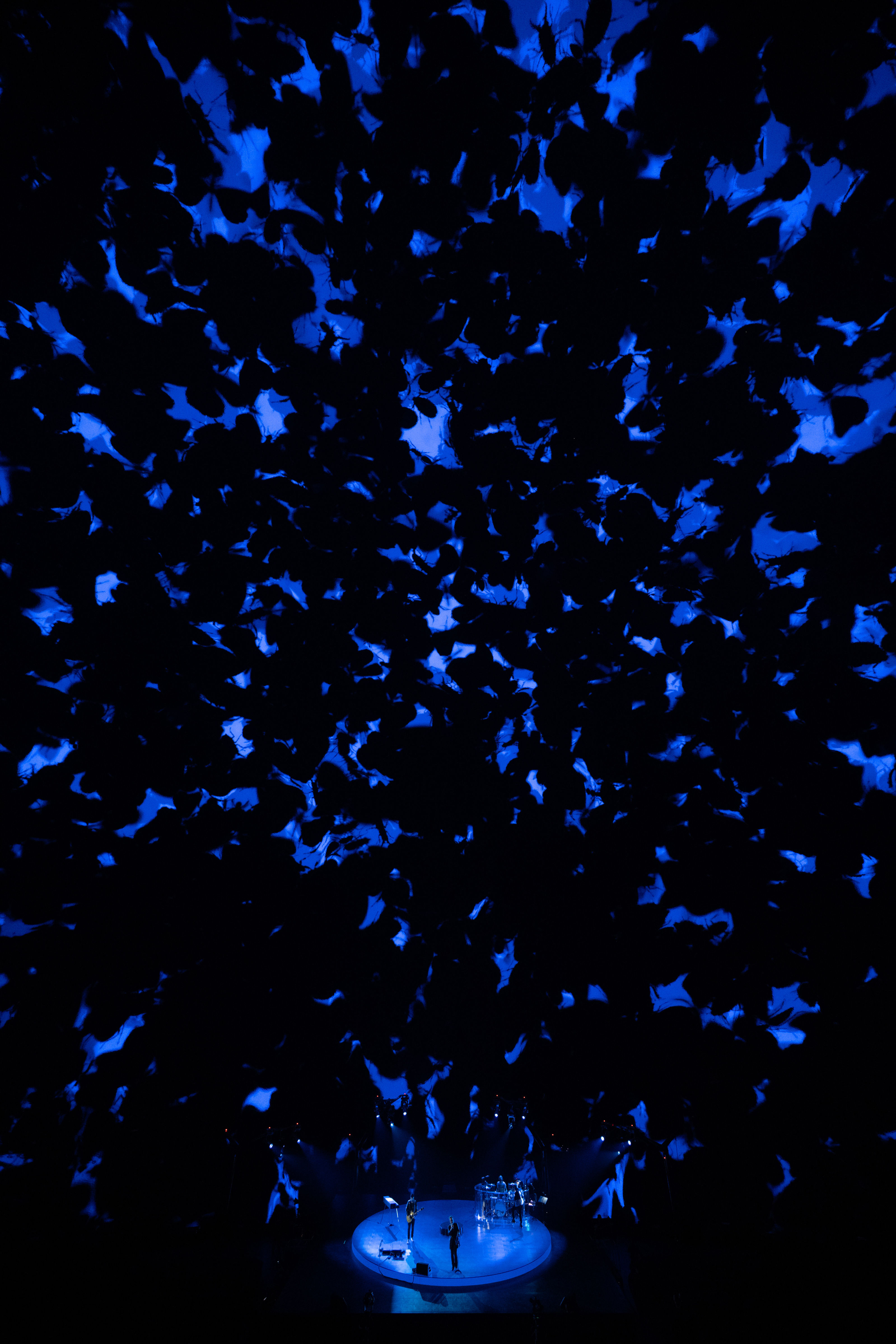

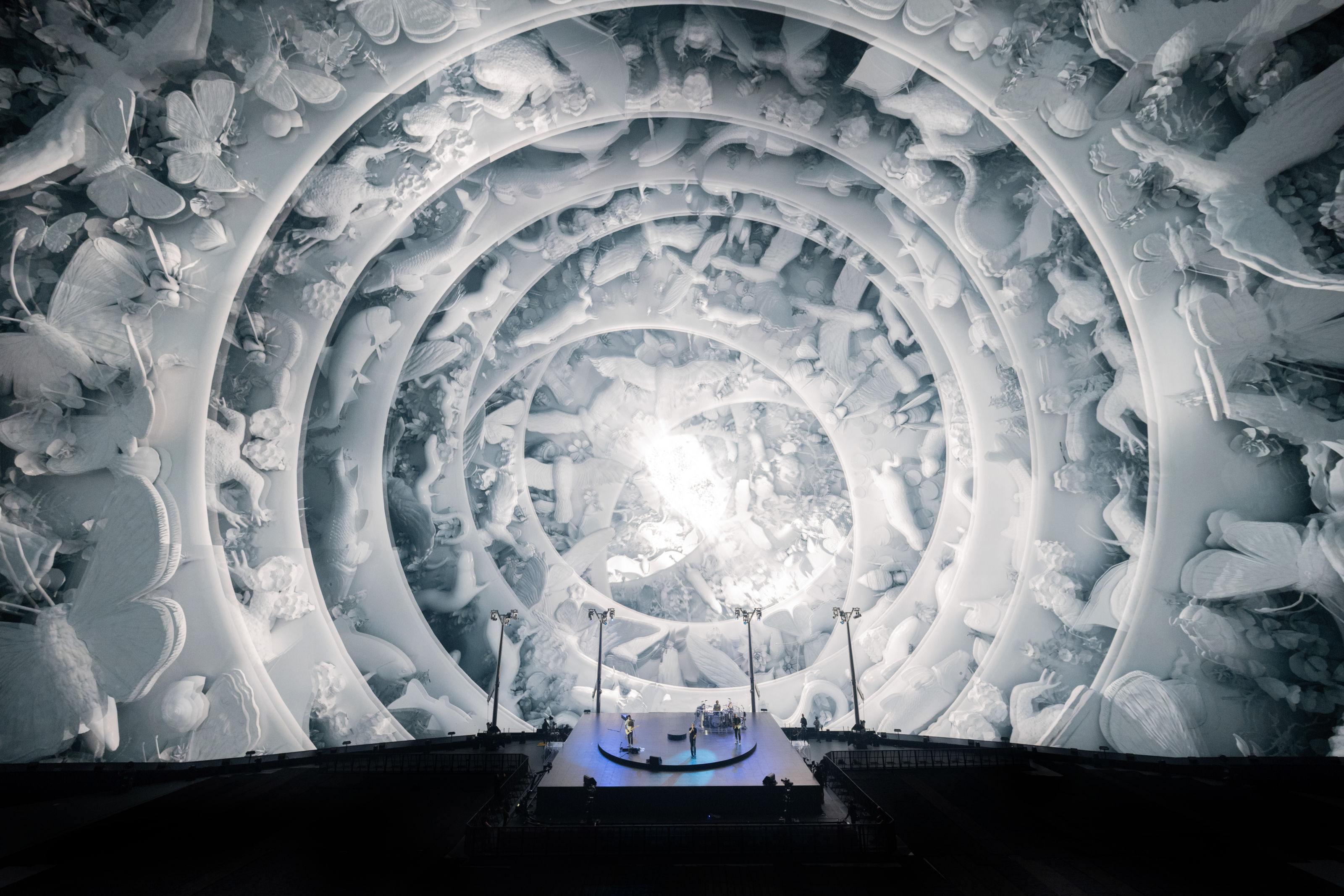

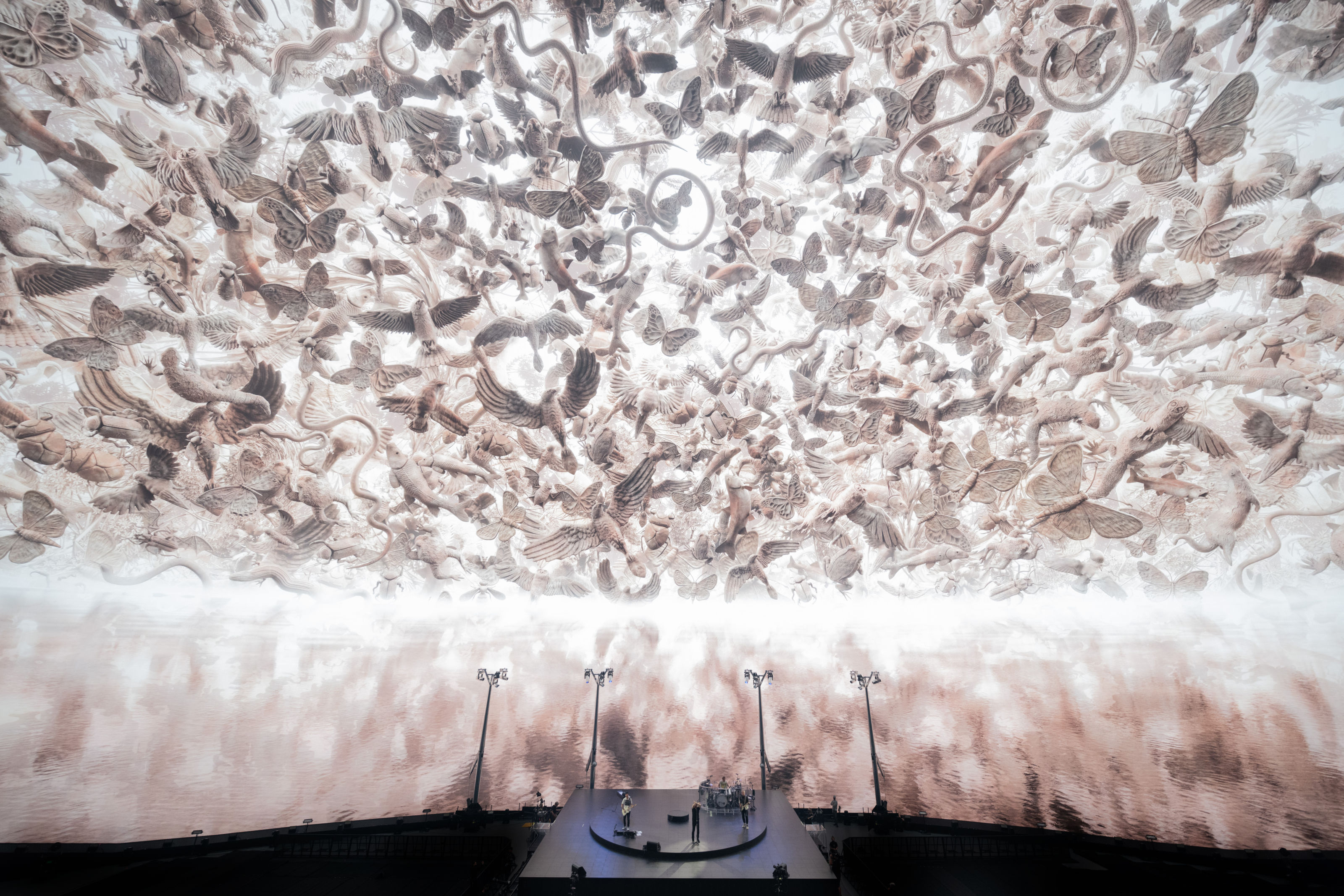

Es Devlin's 'Nevada Ark' is a new piece created for the show

After assembling the U2 family, work began on how to bring the space to life. ‘We’d had demos of the immersion, but there was still around eight months of pre-production work before we could even get in the building,’ Clayton adds, explaining that the Sphere’s bespoke acoustic design posed a number of challenges. ‘You don’t have to be very loud,’ he explains. ‘Whereas it’s much more broad strokes in an arena. As a result, I found I had to concentrate much more – I really have to lock in. You can practically hear the musicians think, and I think we’re playing better as a band [as a result].’ Ultimately, Clayton acknowledges that this is an experiment, but a worthy one. ‘It’s a new way of experiencing music, especially for the younger fans.’

Es Devlin, 'Nevada Ark'

This sense of the rock show as a grand ritual rings especially true for Es Devlin. This year marks ten years of the artist and stage designer’s collaboration with the band, starting with work on what became the Experience + Innocence Tour. For Devlin, whose work spans a vast spectrum from pure pop spectacle to land art, sculpture, installation (including Come Home Again at Tate Modern in 2022), fashion and theatre, one of the first things to celebrate is helping to launch Sphere onto the world stage. ‘It’s quite a privilege to be inaugurating a building,’ she says. ‘It’s quite a sacred thing.’ (The following week she flies to Manchester to oversee a piece inaugurating OMA’s Factory International.)

Es Devlin, 'Nevada Ark'

In the long run-up to the show, Devlin and the rest of creative team – ‘a really tight-knit group’ – began by brainstorming visual concepts of how to treat the space. Devlin admits that she knew a fair bit about the Sphere in advance, noting that ‘every UK and American creative team had been invited to have a look at it – everybody has been sharpening their minds for this space’. The vision that took shape takes the audience on a journey through materiality and light and shadow, exploring the limits of what the screen could make possible.

‘We considered the show to be a little bit like a group art show,’ Devlin says, at pains to point out that although U2 acts as a catalyst, creativity is never imposed. ‘When you have a band as confident in their craft and purpose and status as they are, they’re just so profoundly unthreatened,’ she says. ‘It means they are genuine collaborators who have spent many years engaged with culture. They truly value the work of the artists they engage with.’

Es Devlin, 'Nevada Ark'

‘The amount of trust the band has put in me is incredible,’ Willie Williams admits. ‘It has felt like we’ve had to do the biggest art project in the history of our species whilst running a three-legged obstacle course.’ For Williams, the relationship with U2 continues to push his creative buttons, even if the route and destination have been unconventional. ‘This is someone else’s video surface and we’ll be followed by countless others. I’m just used to starting with hardware,’ he adds. ‘It’ll be a learning curve to see how humans respond to this unique situation – it’s a real dance between intimacy and spectacle.’

Marco Brambilla, 'King Size'

Alongside new iterations of John Gerrard’s series of 'flags', art contributions include Devlin’s ‘Nevada Ark’, a kaleidoscopically dense animated catalogue of the state’s threatened species. There’s also Brambilla’s ‘playful, kitsch’ piece ‘King Size’, which accompanies the song ‘Even Better Than the Real Thing’. Brambilla’s contribution evolved from an AR project that used AI-generated Elvises, a familiar Vegas touch point.

‘Elvis’ rise and fall mirrors the rise and fall of America, in a way,’ Clayton muses, before adding that if there’s one theme that runs through the entire show, it’s the relationship between the consumer economy and climate change. ‘It’s not obvious or straightforward,’ says Clayton, ‘but the art and artists have created a narrative that embodies the idea of community. We’re all part of the problem and the solution.’

Es Devlin, 'Nevada Ark'

The Sphere itself could be read as a symbol of the post-capitalist panopticon, a literal screen on which to project our hopes and fears. Devlin, for one, is sanguine about the resources expended to create the venue and the show, explaining that sustainability is about preserving the spaces and rituals that are most precious. ‘I want to sustain the kind of life where we can all gather together and sing,’ she says, describing the artist as a conduit for communal emotional experiences or rituals. Is the Sphere a modern cathedral? ‘I could see a return to a form of regular communal weekly gathering,’ she says. ‘We need it like we need air. Urgently.’

John Gerrard

We ask Clayton if the band ever stops to consider its cultural legacy. ‘Yes. We’ve always had very involved creative people around us,’ he replies. ‘For example, Brian Eno had a huge influence on the band, from The Unforgettable Fire onwards. We very much trust our creative department. I’m happy to report that all the gambles and rolls of the dice have paid off.’

Jonathan Bell has since attended the show's opening night – read his U2 in Las Vegas review.

U2:UV Achtung Baby Live At Sphere, 29 September – 16 December 2023, TheSphereVegas.com, VenetianLasVegas.com

U2.com, WillieWilliams.com, EsDevlin.com, MarcoBrambilla.com,

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

We bring you all the best bits from this year’s Goodwood Festival of Speed

We bring you all the best bits from this year’s Goodwood Festival of SpeedAs car makers switch their allegiance to the sunny West Sussex countryside as a place to showcase their wares, a new generation of sports cars were sent running up that famous hill

-

Stay at Patina Osaka for a dose of ‘transformative luxury’ in western Japan

Stay at Patina Osaka for a dose of ‘transformative luxury’ in western JapanFrom nature-inspired interiors to sound-tracked cocktails and an unusually green setting, Patina Osaka is a contemporary urban escape that sets itself apart

-

12 photographers vie for Prix Pictet 2025, lenses firmly focused on sustainability

12 photographers vie for Prix Pictet 2025, lenses firmly focused on sustainabilityPrix Pictet is the world’s leading award for photography and sustainability. Here’s how the 2025 shortlist responded to this cycle’s theme, ‘Storm’

-

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raising

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raisingAt Art Omi sculpture and architecture park, NY, Besler turns barn raising into an inclusive project that challenges conventional notions of architecture

-

The dynamic young gallerists reinvigorating America's art scene

The dynamic young gallerists reinvigorating America's art scene'Hugging has replaced air kissing' in this new wave of galleries with craft and community at their core

-

Meet the New York-based artists destabilising the boundaries of society

Meet the New York-based artists destabilising the boundaries of societyA new show in London presents seven young New York-based artists who are pushing against the borders between refined aesthetics and primal materiality

-

Mystic, feminine and erotic: the power of Penny Slinger’s bodies as landscape

Mystic, feminine and erotic: the power of Penny Slinger’s bodies as landscapeArtist Penny Slinger continues her exploration of the sacred, surreal feminine in a Santa Monica exhibition, ‘Meeting at the Horizon’

-

Photographer Geordie Wood takes a leap of faith with first film, Divers

Photographer Geordie Wood takes a leap of faith with first film, DiversGeordie Wood delved into the world of professional diving in Fort Lauderdale for his first film

-

New book celebrates 100 years of New York City landmarks where LGBTQ+ history took place

New book celebrates 100 years of New York City landmarks where LGBTQ+ history took placeMarc Zinaman’s ‘Queer Happened Here: 100 Years of NYC’s Landmark LGBTQ+ Places’ is a vital tribute to queer culture

-

A major Takashi Murakami exhibition sees the world in kaleidoscopic colour

A major Takashi Murakami exhibition sees the world in kaleidoscopic colourThe Cleveland Art Museum presents 'Takashi Murakami 'Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow', exploring outrage and escapist fantasy

-

Ai Weiwei’s new public installation is coming soon to Four Freedoms State Park

Ai Weiwei’s new public installation is coming soon to Four Freedoms State Park‘Camouflage’ by Ai Weiwei will launch the inaugural Art X Freedom project in September 2025, a new programme to investigate social justice and freedom