'John Gerrard: Farm' at London's Thomas Dane Gallery explores the unfathomable proportions of modern technology

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Viewing, or perhaps watching John Gerrard's Farm (Pryor Creek, Oklahoma) - currently plugged in and on display at the Thomas Dane Gallery in London's Mayfair - you circumnavigate, at eye level, one of Google's huge server centres or 'data farms'. And very slowly; a slow walking pace that makes it feel as if you are going nowhere until something new enters the screen, left or right. And when you do view it, the time and day and date in this digitally modelled Oklahoma will fit with real time and the stars will sit in the right place in the digital sky. Time, says Gerrard, is a third dimension in his work.

This particular data farm, he says, looks much like the huge industrialised pig farms lined up - like a Donald Judd piece he suggests - in that area of the US (notorious for its devastating depression-era dust bowl, a particular fascination for Gerrard).

Last year Gerrard asked Google if he could photograph this data farm. Not surprisingly, given the security around such sites, they said no. So he hired a helicopter to take 2,500 images of the farm. And then took the pictures to Vienna, a city he calls 'the secret Berlin', where he works with a group of programmers (otherwise he is Dublin, the city where he was born).

In Vienna he creates complex virtual worlds, modelled using real-time computer graphics, a technology first developed by the military to map out hostile environments but now used by games designers.

Gerrard has an interest in mapping and modelling new kinds of power and influence, of resources and supply. And the sometimes strange, isolated places where that power, or the power behind that power, resides or is stored. 'There is all this ethereal language around the internet; ethernet, the cloud,' Gerrard says, 'but this is what the internet actually looks like.' The piece also asks who and what exactly is being farmed here. 'We think we consume the internet but it actually consumes us', he says.

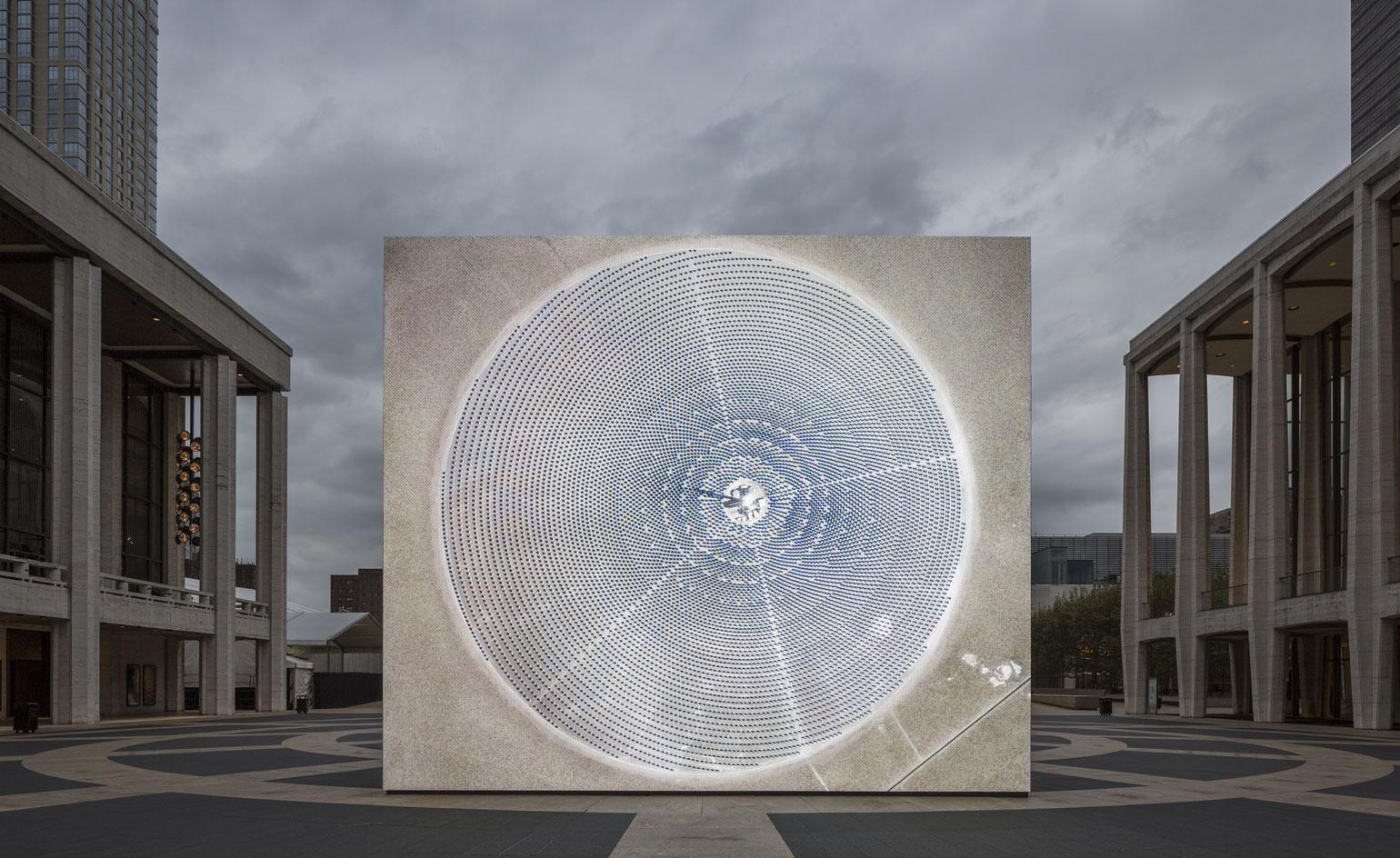

Even more impressive perhaps is the work in Thomas Dane's other gallery on the same street. 'Solar Reserve (Tonopah, Nevada)' was first shown on a giant screen outside the Lincoln Centre in New York late last year. It is a model or portrait of a remarkable new solar power station: 10,000 sun-tracking mirrors called heliostats encircle a tower topped with a giant pot of molten salt. A 'fallen star' Gerrard calls it. His camera-that-isn't-a-camera twists and rises in a golden spiral until we are above the station and it looks like the most astonishing land art or the temple of an alien race. And when it is dark the mirrors lay flat and rest.

These pieces might be the mother of all tracking shots but Gerrard insists that this is not cinema. For one thing, Gerrard's programmes produce 50 frames a second, double that of cinema. There is no narrative arc. More fundamentally, they leave no trace or record. There is no film. And the effect, especially in Farm, and deliberately so says Gerrard, is more painterly than cinematic. It is like a 16th century Dutch still life moving in very slow motion. The effect is mesmerising and disorienting, your understanding of the real and the record and the representation shaken and shifted.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Last year Gerrard asked Google if he could photograph one of its data farms, but due to security reasons, they said no. The artist then hired a helicopter to take 2,500 images of the farm instead

This particular data farm, Gerrard says, looks much like the huge industrialised pig farms lined up in Oklahoma. This area of the US, notorious for its devastating depression-era dust bowl is a particular fascination for Gerrard

Gerrard's artistic interests extend to mapping and modelling new kinds of power and influence. Specifically, the sometimes strange, isolated places where that power, or the power behind that power, resides or is stored

For example, the internet. 'There is all this ethereal language around the internet; ethernet, the cloud,' Gerrard says, 'but this is what the internet actually looks like'

There is no narrative arc in Gerrard's (pictured) exhibition and fundamentally, Gerrard's programmes that produce 50 frames a second leave no trace or record. There is no film. The effect, as Gerard points out, is more painterly than cinematic

'Solar Reserve (Tonopah, Nevada)', a key piece of the exhibition was first shown on a giant screen outside the Lincoln Centre in New York late last year

It is a model of a new solar power station made up of 10,000 sun-tracking mirrors called heliostats, encircling a tower topped with a giant pot of molten salt

Gerrard's camera-that-isn't-a-camera twists and rises until we are above the station and it looks like the most astonishing land art, or the temple of an alien race

This Solar Reserve piece, much like the exhibition, is both mesmerising and disorienting, our understanding of the real and the record shaken and shifted

ADDRESS

Thomas Dane Gallery

3 & 11 Duke Street St James's

London SW1Y 6BN