Donald Judd's work goes on show at David Zwirner in London

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

'Don't call Don a minimalist, or an American artist,' said Flavin Judd, during a walkthrough of his father's exhibition at London's David Zwirner gallery. Fresh off the plane from LA, and with a refreshingly laid-back air, Judd Jr, like Sr, has most definitely resisted labels.

The last retrospective of Donald Judd's work in the UK was at Tate Modern in 2004, and this is the first showing of the artist in a London gallery for almost 15 years. The exhibition, which covers the period 1964 to 1991, has been timed to coincide with Judd's birthday month, and the opening to the public of 101 Spring Street in New York (see W*171), the artist's home and studio from 1968 until his death in 1994.

Judd was, for the most part, averse to gallery shows of his work, preferring permanent installations, which he saw as the best, and most honest, type of presentation - the object's engagement with the space would remain exactly as he intended it. Hence the pieces - 15 huge concrete boxes - located in Marfa, Texas, where Judd decamped to in the 1970s, nearby Chinati Foundation, the contemporary art museum that he founded, and in situ at 101 Spring Street.

Real as opposed to represented space, materiality, singularity - these were the tenets of Judd's philosophy, which the artist laid out in his seminal essay 'Specific Objects', published in 1965. Judd's fellow artists and friends Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, and Jasper Johns were on a similar path, creating new types of work that defied classical definitions. These objects, as Judd stated, were 'neither painting nor sculpture'.

From the early 1960s onwards, Judd developed a lexicon of forms - boxes, stacks and 'progressions' - that were to underpin his oeuvre. The materials he selected to work with, from Plexiglass and plywood to concrete, were pioneering in art at the time. Plywood, which Judd began to use in the early 1970s, gave the artist the opportunity to work with a highly durable material that allowed for different shapes and larger-scale works, which engaged with space in different ways; Untitled (Ballantine 89-31), 1989, made from Douglas Fir plywood, is one such piece on show.

For some of the artist's early metal pieces, the engineering challenges were not inconsiderable. For Untitled, July 6, 1964, a rounded square comprised of cadmium-red enamel (a favoured colour) on galvanised iron, Judd employed local industrial manufacturers.

Colour was key to much of Judd's work, and like his contemporary John Chamberlain, he explored its effects, using enamel on aluminium and coloured Plexiglass, as in Untitled, March 8, 1965 - a transparent pink box transected by steel cables.

Since 1996, the Judd Foundation, whose board is overseen by Flavin Judd and his sister, Rainer, has managed the artist's estate. David Zwirner became the foundation's sole representative in 2010. Despite his dislike of the gallery setting, Judd, one hopes, would have applauded this exhibition. The space may be temporary, but the pieces interact with it beautifully, precisely.

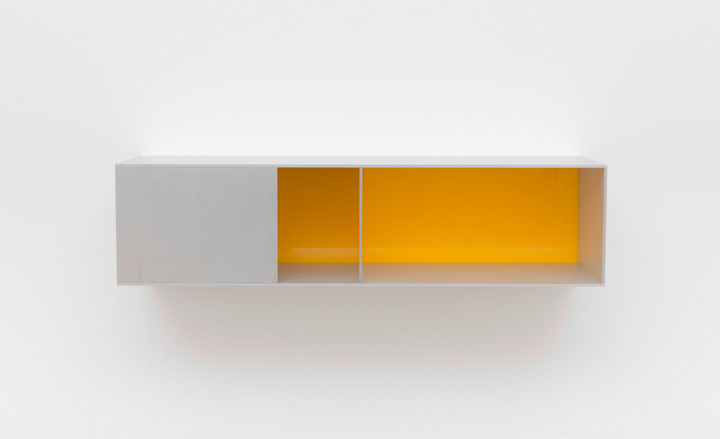

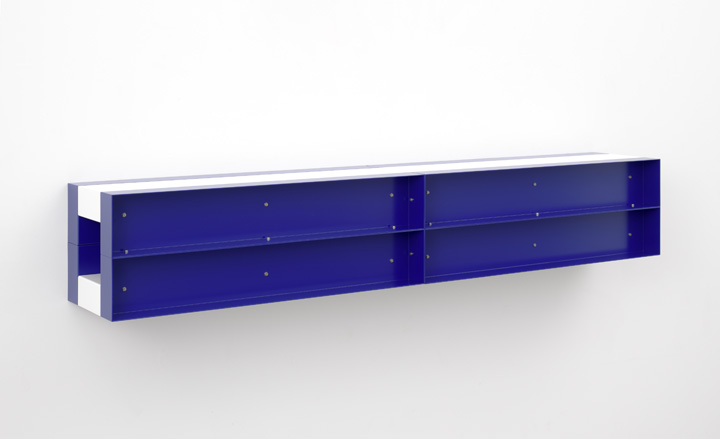

'Untitled (Menziken 91-141)', 1991.

'Untitled (Menziken 88-92)', 1988.

'Untitled', July 6, 1964.

'Untitled (Bernstein 89-1)', 1989.

'Untitled (Lascaux 89-59)', 1989.

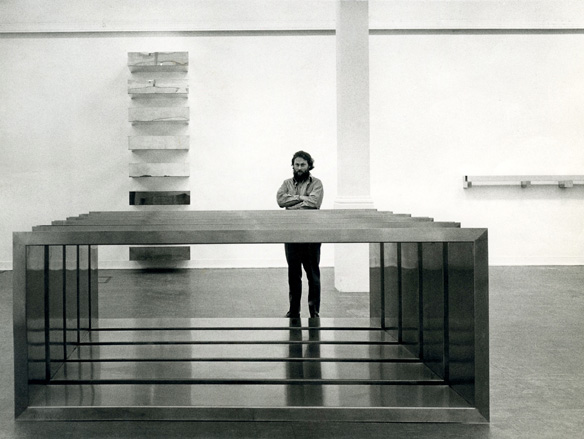

Donald Judd with his work at Whitechapel Gallery, London, 1970. © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy Whitechapel Gallery Archive.

ADDRESS

David Zwirner

24 Grafton Street

London W1S 4EZ

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.