Come Home Again: Es Devlin’s spiritual ode to biodiversity at Tate Modern

Commissioned by Cartier, Es Devlin’s monumental public installation Come Home Again is a space for education, contemplation and conservation action. We visit the artist’s London studio to hear more

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Approached from the south, Es Devlin’s new public artwork in the Tate Modern Garden appears as an architectural homage, a monumental scale model of the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, right across the Thames from Christopher Wren’s original. In Devlin’s piece – titled Come Home Again, and commissioned by Cartier, the dome has been sliced open to reveal its cross-section, brilliantly illuminated and adorned from tip to toe with cut-out sketches of moths, birds, beetles, wildflowers, fish and fungi. At its base are steps that lead up to choral risers, inviting passers-by to immerse themselves in Devlin’s pencil-drawn wildlife.

By day, Come Home Again is a place for contemplation and learning. Stepping into the dome allows the visitor to examine the drawings up close – there are 243 in total, representing the 243 priority species identified by the London Biodiversity Action Plan as declining in numbers in the capital and thus in need of conservation action. In lieu of the prayer books that one might expect in a place of worship, Devlin has placed QR codes that link to a guide to all the species. Just as important is the soundscape, created by Devlin’s habitual music collaborators Jade Pybus and Andy Theakstone, and interspersing recordings of various choirs singing the Latin names of the priority species with the animals’ actual sounds. Every few minutes, the glorious cacophony fades and Devlin’s voice emerges to introduce one of the species. She says its common and Latin names, and brings up a nugget of information that helps us remember the animal. We learn, for instance, that the swift (Apus apus) can fly the equivalent of eight trips to the moon and back in its lifetime.

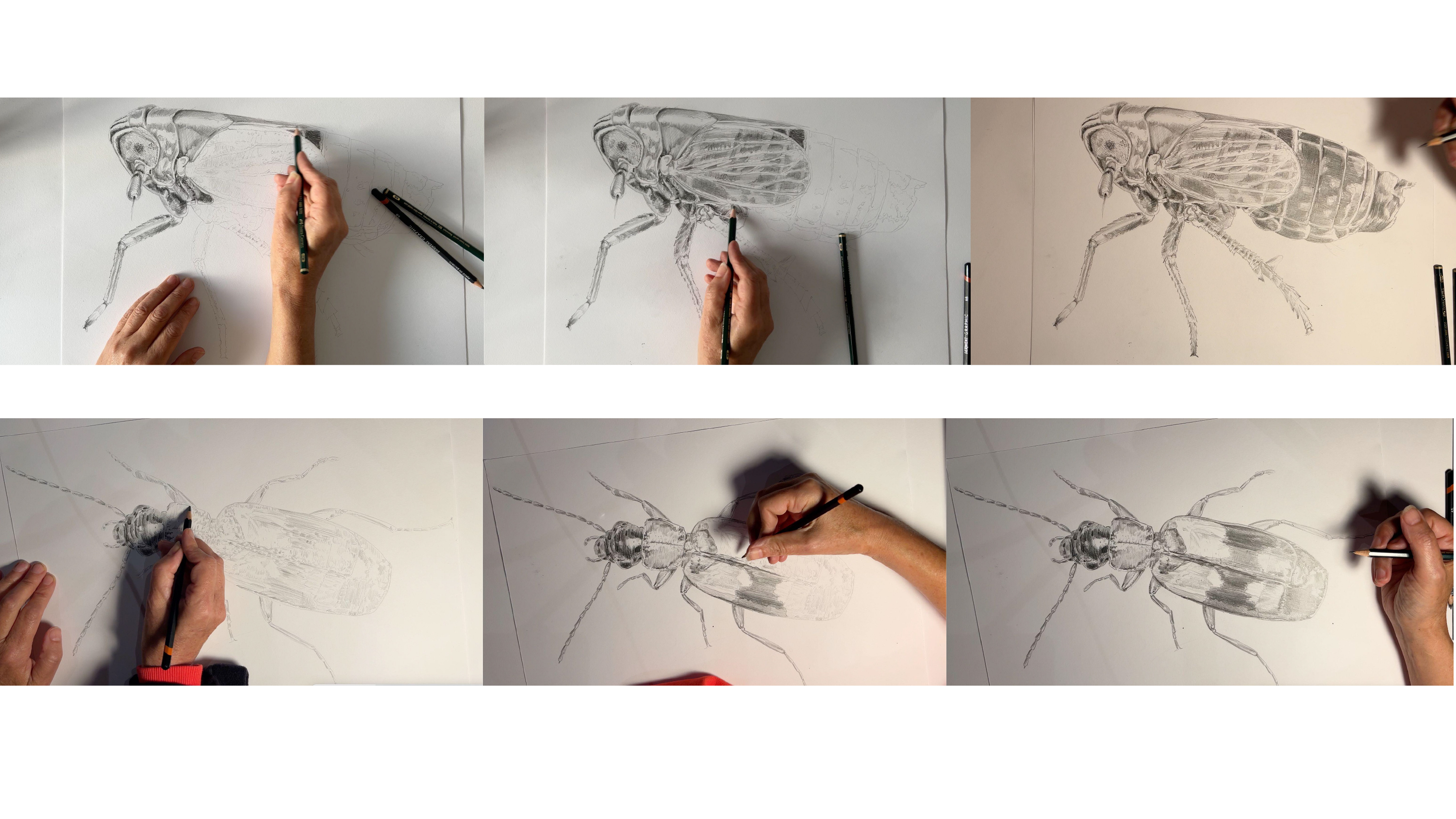

Devlin at work in her south London studio, sketching the tall fescue grasshopper (top) and Mab's lantern (above), two of the animal species on the London Priority Species List and featured in Come Home Again

‘I want to help people learn the names of these animals,’ explains Devlin as we speak in her south London studio two weeks ahead of Come Home Again’s unveiling.

‘Once you know their names, you make a place for them in your imagination – it’s like the memory palace. And you’ll always think of them differently.’

Even for an artist and designer who is used to being in the limelight (Devlin’s portfolio includes stage sets for Beyoncé, The Weeknd, Kanye West and U2, as well as Olympic ceremonies in London and Rio), Come Home Again is a project of great prominence. Tate Modern is among London’s most visited attractions, and even more people pass by its riverfront each day – so the museum is very selective about what it allows to be placed in the garden. The site also has personal significance to Devlin, a native Londoner: ‘For me, Tate Modern is emblematic of a real shift in British culture: its opening coincided with a shift in our character as a country and city, with New Labour and the rise of the YBAs. Suddenly British culture was significant on the world stage, when it hadn’t been for many years.’

The view of St Paul’s from the Tate Modern Garden makes the cathedral a natural starting point for a site-specific commission, but it was a conversation a few years ago with Ben Evans, director of the London Design Festival, that spurred Devlin to join the dots between the two spaces. ‘He said, “Es, you should think about the connection between St Paul’s as a seat of ancient ecclesiastical power, and the Tate as a seat of historical industrial power [the museum building was once the Bankside Power Station], and now a seat of contemporary cultural power. Consider that convergence of energies and think about what you might do”,’ Devlin recalls, as we pore over sketches and renderings of Come Home Again.

Around the same time as her conversation with Evans, Devlin was discovering books on eco-philosophy – encouraged by the likes of Hans Ulrich Obrist and Alice Rawsthorn, and facilitated by the Amazon algorithm. The latter led her to the two most important volumes influencing her worldview and practice today: David Abram’s Becoming Animal (‘he talks a lot about magic, and how we can shift our perceptions if we just interrupt our usual ways of seeing things’, she recaps.), and Joanna Macy’s World as Lover, World as Self. ‘Macy invites you to consider where your self ends, invites you to recognise that you feel selfish, you feel a sense of self-preservation,’ says Devlin. ‘But what if where you considered self to reside was more expansive than just in your own body and in your own mind?’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Much of Devlin’s recent work reflects on Abram and Macy: there’s Forest for Change, which planted 400 trees within the courtyard of London’s Somerset House to raise awareness for the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, and similarly Conference of the Trees, which populated the New York Times’ Climate Hub at COP26 in Glasgow with 197 trees and plants. Her widely photographed and Instagrammed mirror labyrinth, Forest of Us, likewise carries an environmental message; in her words ‘it calls people’s attention to the connection between themselves and the planet’. Come Home Again, with its evocation of animal species which Devlin calls ‘non-human Londoners’, continues in this vein. ‘Humans went through a period of separation from the biosphere in order to learn more about it, in order to specialise. But now we need to reconnect, and come home again to our mutual planet,’ says Devlin, adding that the words ‘dome’ and ‘home’ share etymological roots.

In her bid to better connect with the 243 priority species, Devlin decided to draw each of them in pencil on paper, using photographs as reference material. ‘That kind of observational drawing has not been part of my practice since I was doing my art A-level, but I wanted this sense of submitting to the observation of a life that’s not my own,’ she says. ‘I wasn’t trying to be expressive. So my drawing of the bumblebee isn’t my interpretation of the bumblebee, but an effort to learn the bumblebee’s ways.’

It was a four-month process that involved a few 18-hour days, and gave Devlin ample opportunity to listen to podcasts about London wildlife, and wildlife in general. The fruits of her labour are evident in the ease with which she can now identify each species and rattle off factoids: she points out, for instance, that the streaked bombardier beetle was thought to be extinct until 85 of them were counted in the borough of Tower Hamlets, and has since become a subject in the artwork of Sonia Boyce, who won the Golden Lion at this year’s Venice Biennale.

Within Come Home Again, Devlin’s 243 sketches have been enlarged, printed on a sustainably sourced birch ply, cut out, and displayed across the dome’s cross-section, with strips of LEDs stuck on the back for illumination (these will go back to inventory after the exhibition). The structure is made in recycled steel and stretched fabric, and she’s opted for an environmentally friendly matte paint finish, all to keep the installation’s carbon footprint to a minimum and thus align with its message.

Elegant and impactful as it is in the daytime, it is at sunset that Come Home Again truly comes to life. Each evening until 1 October, a London-based choral group will come to the installation and sing their interpretation of choral evensong, which members of the public can enjoy free of charge and without prior booking. Devlin got the idea from her visit to St Paul’s, where she observed the daily ritual that marks the moment as the day turns to evening: ‘listening to evensong, I thought, where else would you get this experience? They’re going to sing whether you turn up or not, so it’s not a performance. It’s actually a call to prayer, a relic of a time of matins, nones and vespers. You feel like you’re part of an ancient mode of telling time. Whoever you are, you can walk in and be surrounded by this extraordinary body of music.’

Devlin putting the finishing touches on Come Home Again

The choral lineup is illustrious and reflective of London’s cultural makeup, ranging from the award-winning Tenebrae, to the London Bulgarian Choir and the South African Cultural Gospel Choir UK. They will be singing in English, Latin, Bulgarian and Xhosa – ‘I’m interested in the parallel concerns of diminishing biodiversity and diminishing linguistic diversity,’ Devlin says. ‘We’re homogenising, and our ethnosphere has also been impoverished in parallel to the biosphere. There’s an extraordinary document on endangered languages, and how you feel when you read it is also how you feel when you see the last polar bear on the last floating bit of ice. I wanted to make that connection too.’

She is particularly looking forward to the performance by The Choir with No Name, a chorus for homeless and marginalised people to experience the joy of singing together. ‘I defy anyone not to cry on that night. Because we’re talking about homes, and here we have people who don’t have homes, singing their hearts out. I think it’s going to be incredibly moving.’

Devlin likes to include a clear call-to-action with each installation. So just as Forest of Us in Miami encouraged visitors to make a donation to Instituto Terra, a non-profit organisation dedicated to recovering the Atlantic Forest, Come Home Again encourages audiences to contribute to and engage with the London Wildlife Trust, which protects, conserves and enhances the capital’s wildlife and wild spaces.

It’s a cause that equally resonates with Cartier, with whom Devlin has a longstanding relationship (She cites the 2019 exhibition ‘Trees’ at Fondation Cartier, which brought together artists, botanists and philosophers, as an inspiration for her recent practice). Says Cyrille Vigneron, CEO of Cartier, ‘with Come Home Again, Es Devlin has created a unique and thought-provoking work of art, a choral sculpture representing how inspiring, yet fragile the beauty of the world can be, calling to preserve earth’s natural biodiversity.’

Ultimately, Come Home Again offers a message of hope, suggesting that if we take swift and decisive action to remedy past wrongs, we can return to a happier state of equilibrium with the planet. As Devlin says in the installation’s soundscape, quoting Joanna Macy: ‘May we turn inwards and stumble upon our true roots in the intertwining biology of this exquisite planet. [...] Now it can dawn on us. We are our world knowing itself. We can relinquish our separateness, we can come home again.’

Come Home Again, until 1 October 2022 at the Tate Modern Garden, Bankside, London SE1, esdevlin.com, cartier.com, wildlondon.org.uk

TF Chan is a former editor of Wallpaper* (2020-23), where he was responsible for the monthly print magazine, planning, commissioning, editing and writing long-lead content across all pillars. He also played a leading role in multi-channel editorial franchises, such as Wallpaper’s annual Design Awards, Guest Editor takeovers and Next Generation series. He aims to create world-class, visually-driven content while championing diversity, international representation and social impact. TF joined Wallpaper* as an intern in January 2013, and served as its commissioning editor from 2017-20, winning a 30 under 30 New Talent Award from the Professional Publishers’ Association. Born and raised in Hong Kong, he holds an undergraduate degree in history from Princeton University.