Gallerists John and Gretchen Berggruen find a new opportunity in San Francisco

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

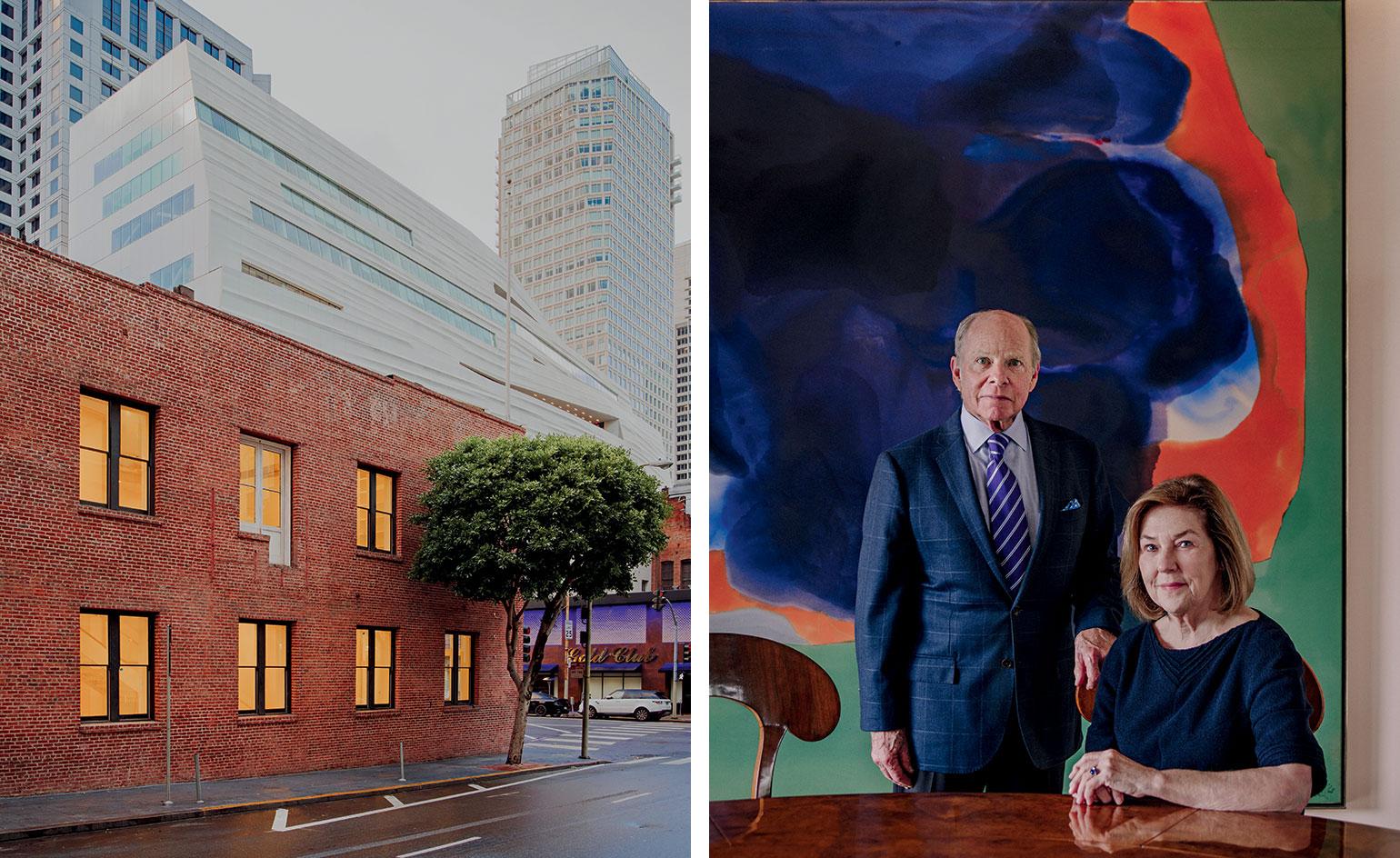

After 45 years of showing modern and contemporary art at their gallery near Union Square, now San Francisco’s hub of fine hotels and high-end retail, John and Gretchen Berggruen considered closing the doors permanently to pursue private sales. Skyrocketing rents in the area had driven out many of their established colleagues and they too were feeling the pressure, too. They could retire and still take credit for building the reputations of Bay Area artists such as Wayne Thiebaud and Richard Diebenkorn. In their small but wealthy community, they had cultivated a dedicated group of collectors.

But in February last year, a tantalising opportunity presented itself: a 1908 brick building in the historic district close to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which was recently expanded by Snøhetta and is now the second largest art museum in the US. Once a restaurant, the structure was also adjacent to the brick building owned by Crown Point Press, in which Larry Gagosian opened a gallery in spring 2016. The remarkable location alone seemed a sign to carry on.

Gretchen’s daughter Jennifer Weiss, an architect based in San Francisco, took on the substantial renovation of the two-storey, 10,000 sq ft building. The structure is situated in a historic preservation zone, so the challenges were considerable and time consuming, from installing white sheetrock over red-brick interior walls to constructing a glass staircase that connects the subterranean galleries and storage with the central gallery and top-floor offices.

‘I thought, what a wonderful project. Boy, was I a fool,’ says John, 73, good-naturedly. Gretchen, 71, agrees: ‘It was more demanding than we expected.’ Their new gallery finally opened in January with an exhibition titled ‘The Human Form’ (the pair have long championed the figurative tradition), with paintings by artists including Pablo Picasso and George Condo.

Their wide-ranging passions and curatorial smarts are also on view at their home in the historic district of Russian Hill. One of few residences to survive the 1906 earthquake, the 1854 shingle-covered house has stunning views of the bay and downtown. In 1998, it was restored and renovated by architect Robert AM Stern, who described it as ‘one of the oldest houses on one of the highest points in the city’.

The walls of each room display the Berggruens’ own significant collection. The top-floor living space is anchored by a 1968 David Hockney painting of a window looking out over sailing boats – it’s a good match for their own windows and vista. On the opposite wall is Ed Ruscha’s 1972 word painting Faith, while the dining room features large works by Diebenkorn and Helen Frankenthaler. Modern furnishings are mixed with sleek antiques. The late Randolph Arcinsky, of furniture company Randolph & Hein, assisted with the decor and John purchased many of the art deco and Biedermeier pieces to be incorporated into the design. It is not a showroom, but a place where people are welcomed and entertained.

The top-floor living room of the Berggruens’s 1854 home, in the Russian Hill District of San Francisco, features portrait of Mrs Jean Wight, 1931, by Frida Kahlo, and one of Ed Ruscha’s word paintings, ’Faith’, 1972

Gretchen says one motivating factor for continuing to operate a gallery was going through their own archives, to compile the 2015 exhibition and catalogue ‘Looking Back: 45 Years’. This reminded the Berggruens that, in addition to many artists from the Bay Area, they had given the first West Coast show to American modernist Georgia O’Keeffe and regularly presented Los Angeles artists such as Ruscha. To stage the ‘Looking Back’ exhibition, they borrowed some 40 pieces from collections they had helped to build. ‘It’s the creative part of the work,’ says Gretchen.

Seeing what they had accomplished re-energised them. ‘It gave me the sense that there was so much more that could come to a city like this. If we want to stay viable, we need to keep our programme as vibrant as it has been in the past,’ Gretchen adds.

With cash-rich tech titans and venture capitalists now abundant in the Bay Area and throughout northern California, the pair find themselves working with younger generations of aspiring collectors. The Berggruens, both charming and erudite, hope to continue educating and placing artists’ work with these freshly curious entrepreneurs and professionals.

Yet the very factors that have created a new collecting class are also driving out the creative class, the artists who once lived comfortably in the Bay Area. The Berggruens now look to the East Coast and elsewhere for their new artists. To carry on in this environment, they have reached out to those who have not had much exposure in the Bay Area, such as internationally recognised New York-based artist Spencer Finch. ‘We love the interchange between artists and collectors,’ says Gretchen. ‘And galleries in Europe are great as collaborators,’ adds John.

John comes from solid art-professional stock. During the Second World War, his German father, Heinz, lived in San Francisco and was a curator at the Museum of Modern Art. When John was two, his parents divorced (his mother was Lillian Zellerbach, of a prominent San Francisco family) and Heinz moved back to Europe. A brief affair with Frida Kahlo contributed to the break-up.

The Berggruens in their new gallery with architect Jennifer Weiss, Gretchen’s daughter, who renovated the building. The project involved installing drywall over the brick interior walls and constructing a glass and timber staircase

John remained in the US while, across the Atlantic, his father continued to build a respected collection of modern art, including serious holdings of work by Paul Klee. Last autumn, the majority of Heinz’s donation of 90 works by Klee was shown at the Met Breuer museum in New York, and other collections are housed in the Museum Berggruen in Berlin. John believes his passion for art comes from ‘genetic transference’ rather than environmental influence; his half-brothers are art historian and curator Olivier Berggruen and billionaire collector and philanthropist Nicolas Berggruen.

John opened his gallery in 1970. In 1978, Gretchen started working with him, having been involved in public art projects. John credits her with much of their success. ‘It was a galactic shift,’ he says. ‘She brought sensitivity as well as structure to the business.’ Nine years later, they were married. John, never missing the opportunity for a joke, says, ‘She wanted a raise. I told her I have another idea.’ And now the genetic transference continues: their son, Alex, works in contemporary art at Christie’s in New York.

Now that the new gallery is open, John can put all the irritation over delays and expenses behind him. It is time to move forward. With the animated expression of a young boy, he exclaims, ‘It is exciting for us.’

As originally featured in the April 2017 issue of Wallpaper (W*217)

The Berggruens’ private collection also includes David Hockney’s ’California Seascape’, 1968, and Martin Puryear’s sculpture, ’Le Prix’, 2005

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Berggruen Gallery website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.