Bridget Riley hits the spot at Hayward Gallery

After seven decades, the op art doyenne proves to be as perception-shifting as ever in the largest survey of her work to date

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

How do you do a 70-year career justice? London’s Hayward Gallery might just have the answer, with the most extensive and comprehensive exhibition of Bridget Riley to date. This non-chronological, thematic show is not one you can saunter through. ‘I encourage you to put the camera down, stand in front of it, give it some time and let your eyes settle into each image, because I think that’s when the magic starts to happen and the image starts to dance,’ says Hayward Gallery senior curator, Cliff Lauson.

It’s a treat to glimpse into a pre-career Riley, from studies she produced as a schoolgirl in the 1940s, including an impressive copy of Jan van Eyck’s A Man in a Red Turban, and a subsequent chapter of work from her time at the Royal College of Art where she cut her teeth on life models.

In the late 1950s the British art scene was rife with ego and jarring commentary on the swelling consumer boom. While Francis Bacon was wielding his infamous brush towards scenes of despair and Richard Hamilton was asking, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, Riley was busy plotting a retinal takeover. Unlike some of her peers, she wasn't interested in misery and self-indulgence – her primary interests were pleasure and the eye, and how paint and form could manipulate them both.

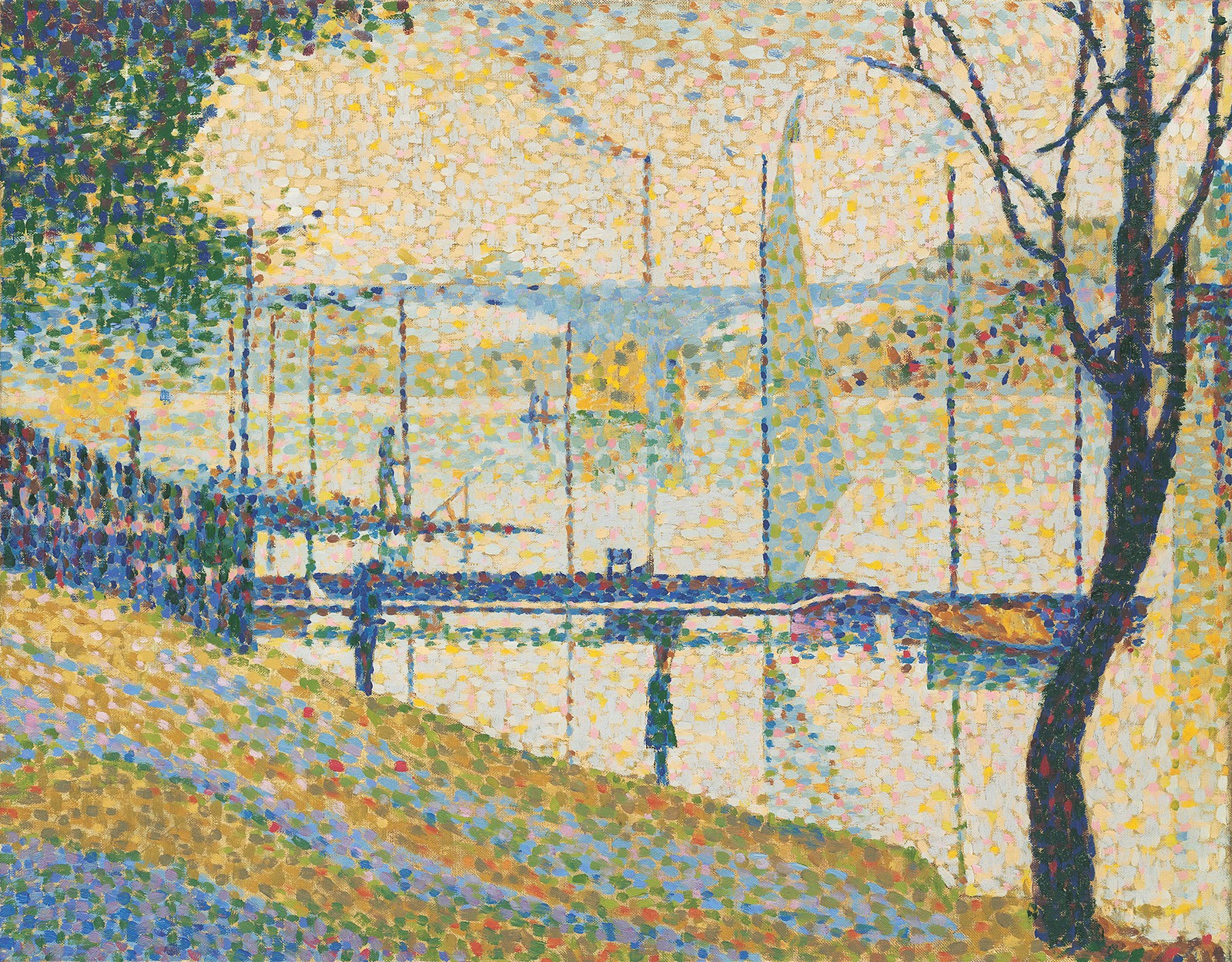

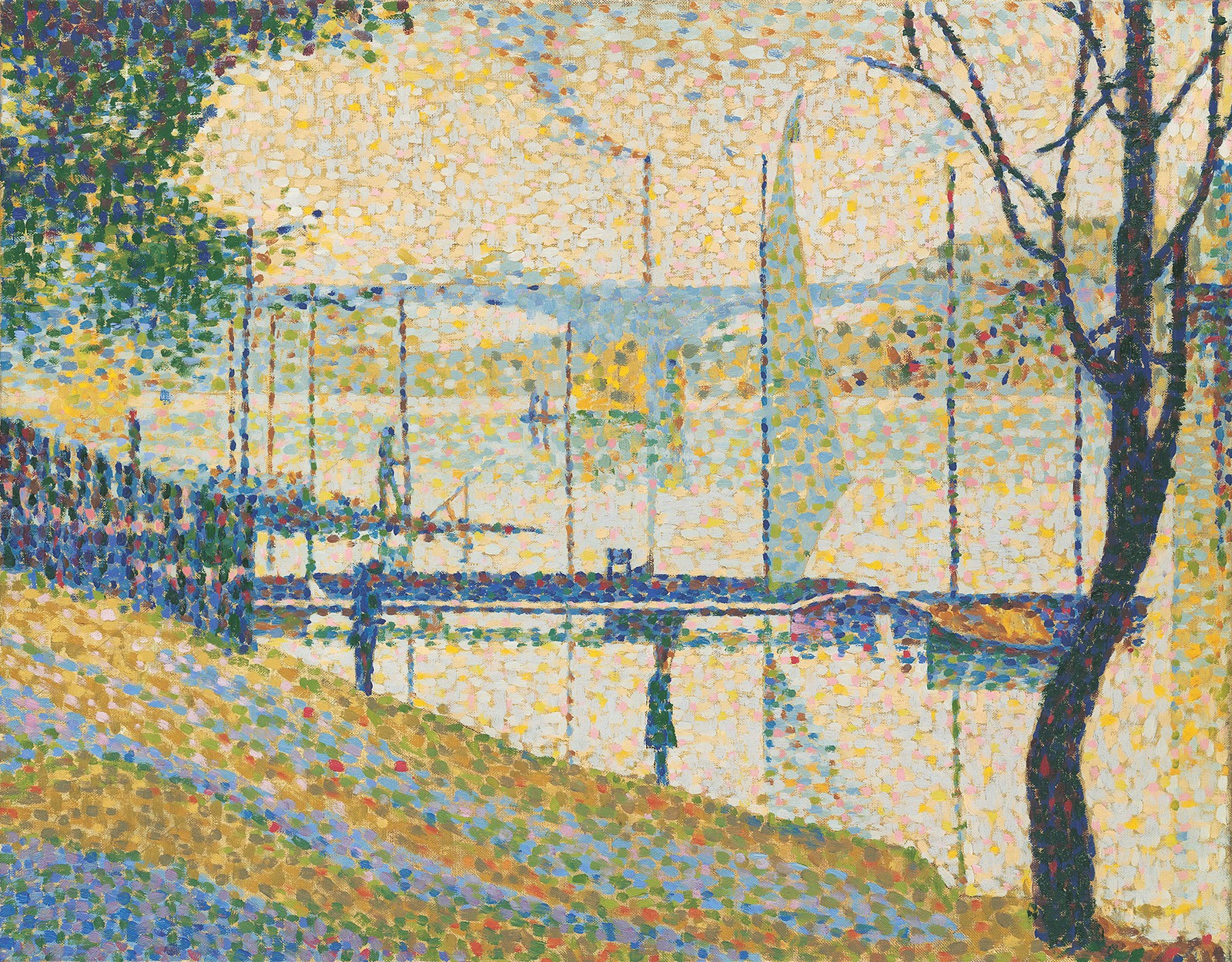

Copy after ‘Le Pont de Courbevoie’ by Georges Seurat, 1959, by Bridget Riley, oil on canvas.

Spurred on by a Jackson Pollock exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1958, she began inventing her own fiercely intellectual, abstracted science. She encountered Georges Seurat’s Bridge at Courbevoie and was smitten, studying, deciphering and reproducing it. You can feel the painstaking calculation and the pacing back and forth to the canvas. ‘This is not child’s play,’ says Lauson. ‘It takes a huge amount of skill, knowledge, understanding and study to try and emulate something that somebody had spent decades themselves trying to emulate.’

In the 1960s, the world was mulling over the threat of nuclear disaster and Aldous Huxley was chronicling the effects of hallucinogenic drugs. But Riley was in a far out dimension of her own, experimenting with monochrome and all sorts of grey matter. She broke into abstraction in 1961 with a work called Kiss and the world began to take notice.

‘The one thing about abstraction – when I began to be curious about it – is that it doesn't have to serve a purpose. It doesn't have to represent something,’ Riley explains on the eve of her show opening. ‘Colours, lines, shapes and spaces don't have to stand in for double duty. They are and can be themselves. Then one is curious about what they can do, allowed to stand on their own two feet.’

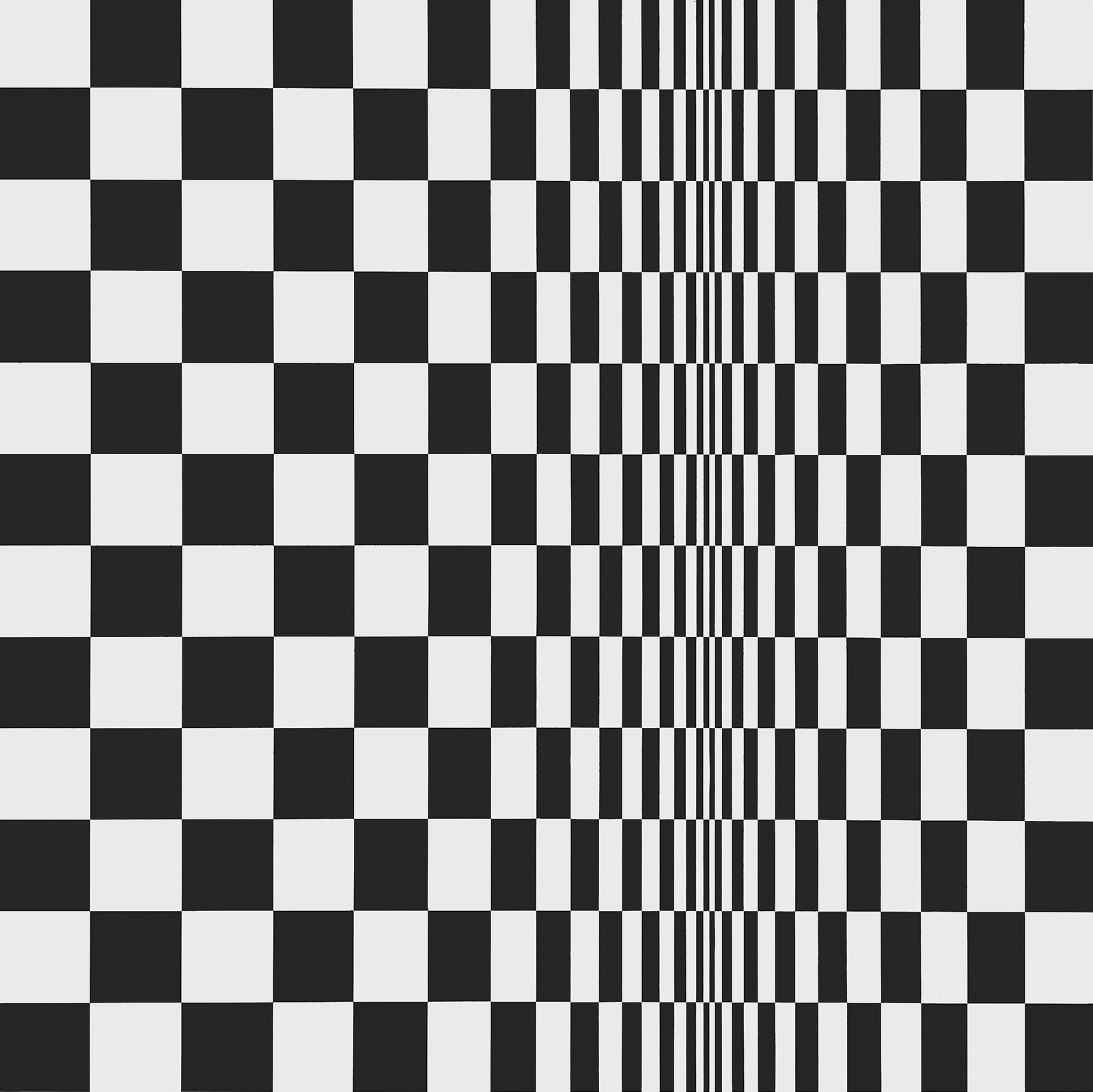

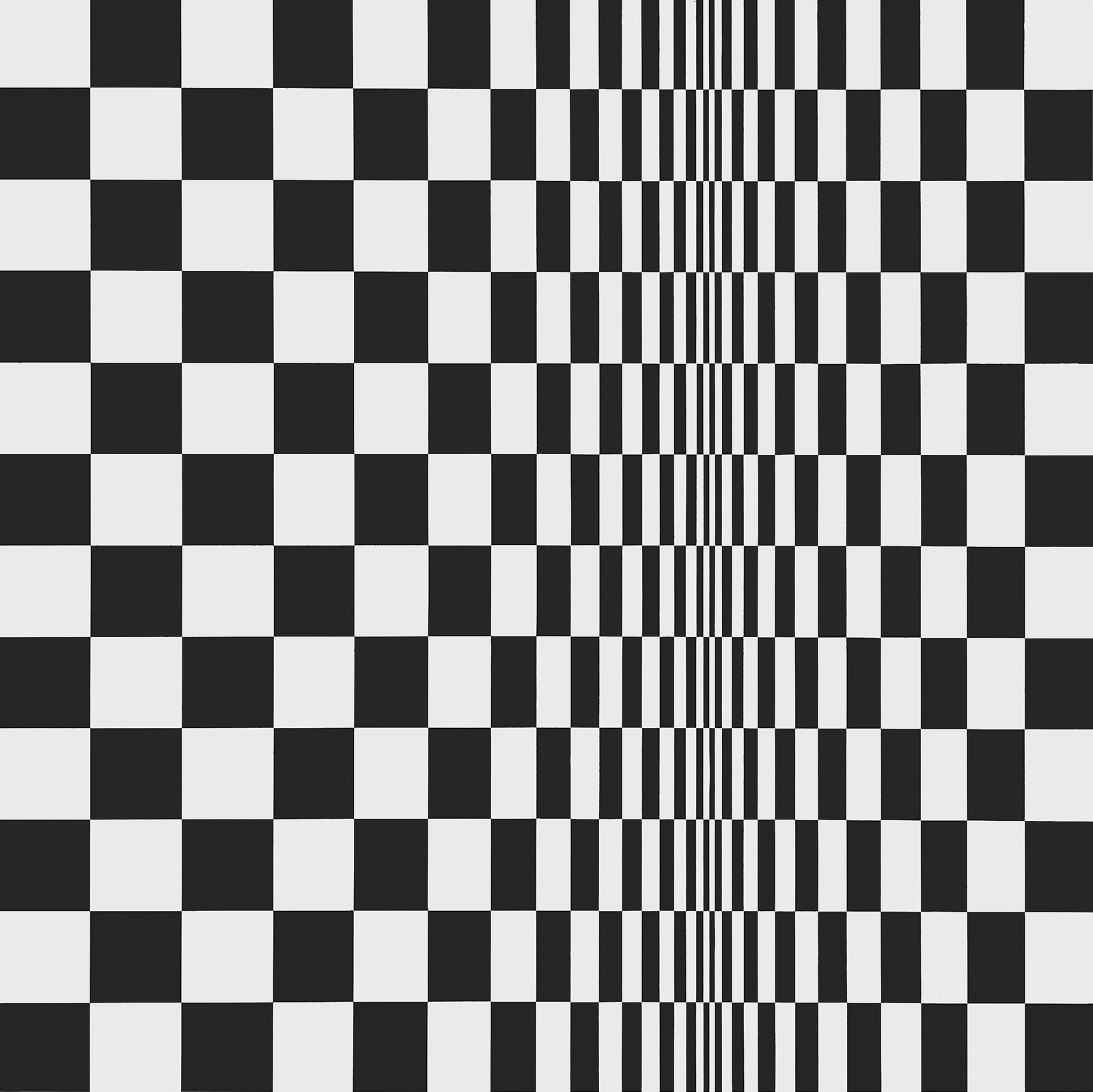

Movement in Squares, 1961, by Bridget Riley, synthetic emulsion on board.

In these black and white works (for which the Hayward knocked down a wall and set aside a whole new room to house), the longer you look, the more you query your mind’s lucidity. Riley puts every conceivable shape through its paces, resulting in a rigorous, syncopated musicality where dots and lines pulsate and gyrate and familiar shapes look alien. Lock eyes with Movement in Squares, and five seconds later you’re being squashed between two contorting walls. A recent monochrome wall painting, Quiver 3, leaves you questioning the definition of a triangle.

As the Hayward was being built in the late 1960s, Riley was in her heyday. Two years later, she introduced her work to this temple to brutalism. In 1971, the gallery hosted her first major solo, followed by another in 1992. She stepped up as co-curator for a Paul Klee show and participated in the gallery’s publication The Hayward Annual 1985. But it’s not just an almost 50-year affinity with these austere walls which makes the current show feel like a natural return to home, it’s the network of malleable galleries and constant variation of shape and pace that make it a kindred spirit in architectural form.

Colours, lines, shapes and spaces don’t have to stand in for double duty. They are and can be themselves

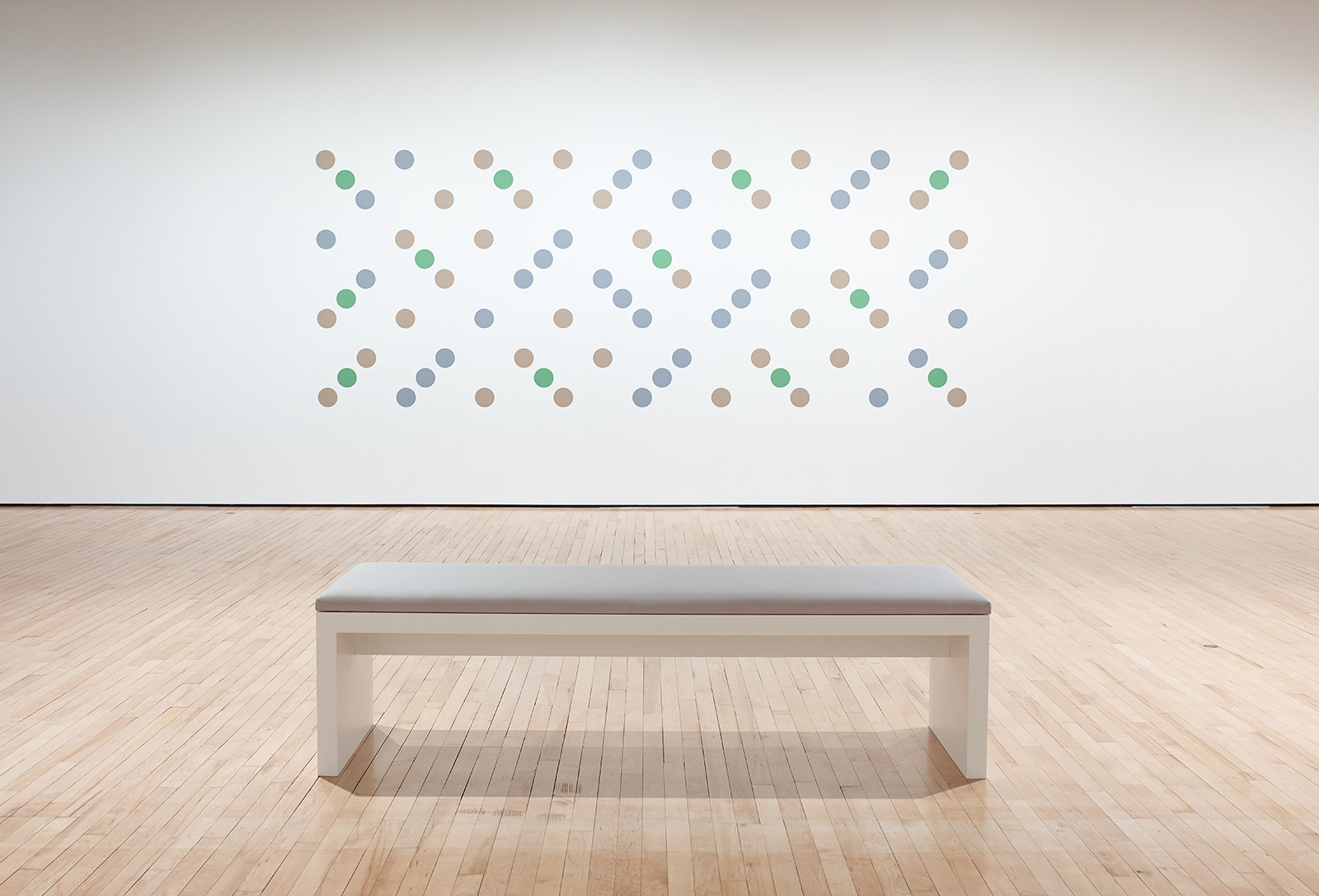

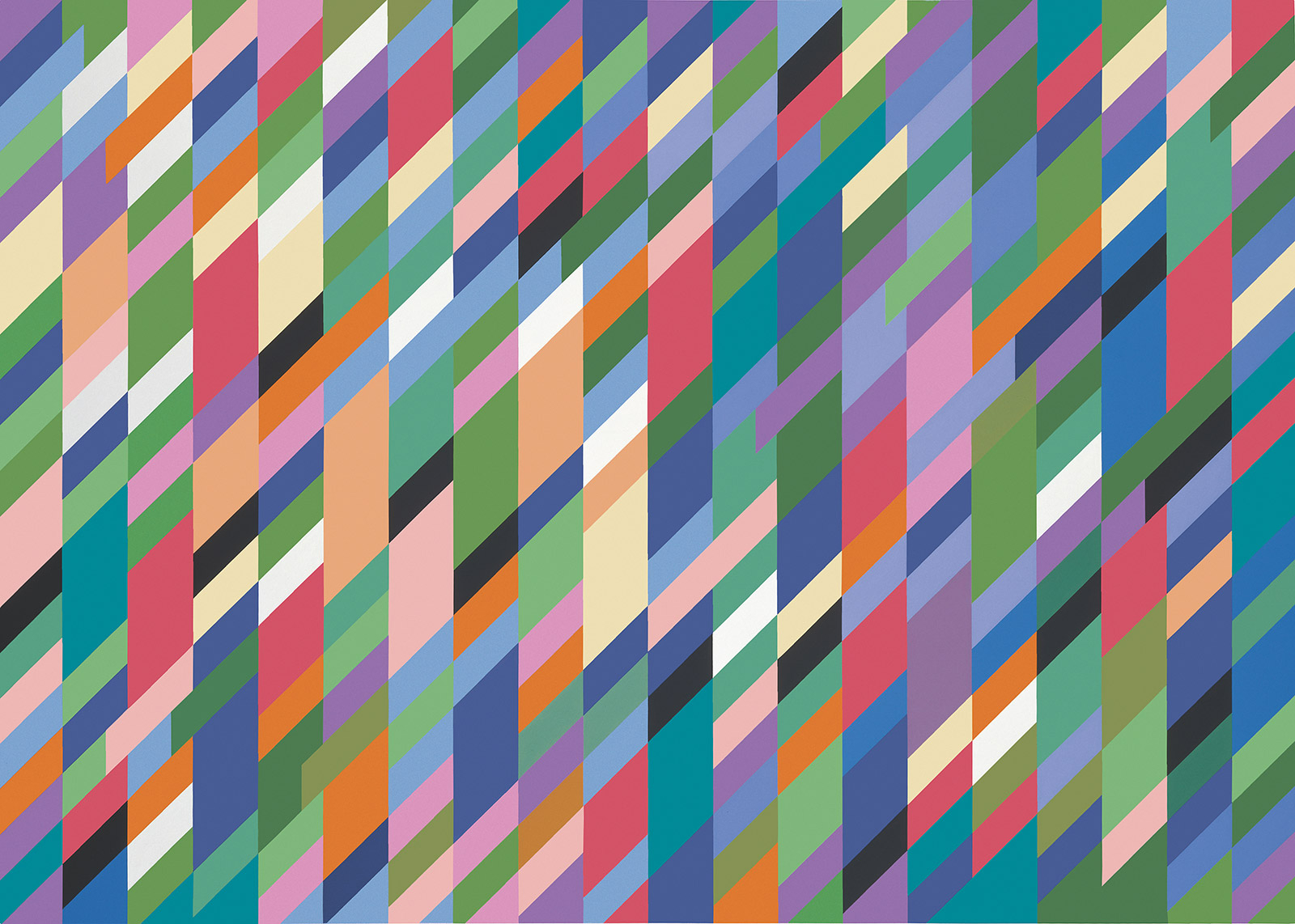

Her enormous stripe paintings dominate the ground level space. Colours alter and clash; apparently straight lines bend and constrict. Upstairs, things get curvaceous but uncharacteristically formal. The luridly coloured wall painting Rajasthan does more to the stomach than the eyes. New work developed this year, like the dotty Measure for Measure 36 executed in muted pastel tones, is atypically sullen and lacking the usual pop, but by this point we could all use a time out.

The most exciting part of the show isn’t the trio of enormous site-specific wall paintings that take a dozen-strong team weeks to make. Nor is it Riley’s only three-dimensional work, a spiral enclosure called Continuum [Reconstruction]. It’s a room upstairs, where we get to peek into the work’s conception, straight into her so-called ‘eye’s mind’.

View of ‘Bridget Riley’ at Hayward Gallery, London. © The artist.

Here we can see the plotting and mapping on graph paper and can almost hear the mind ticking. What results in forms that border algorithmic, are in fact the product of one brain, and an eager band of assistants. The ever-enigmatic artist puts it best herself: ‘The working process is one of discovery and it is worth remembering that the word discovery implies an uncovering of that which is hidden.’

If Riley’s career were a carol, this would be the descant. If the exhibition proves anything, it’s that the matriarch of op art has still got it. The ability to tickle the senses, bewilder the neurons and leave imprints on your eyes for hours to come.

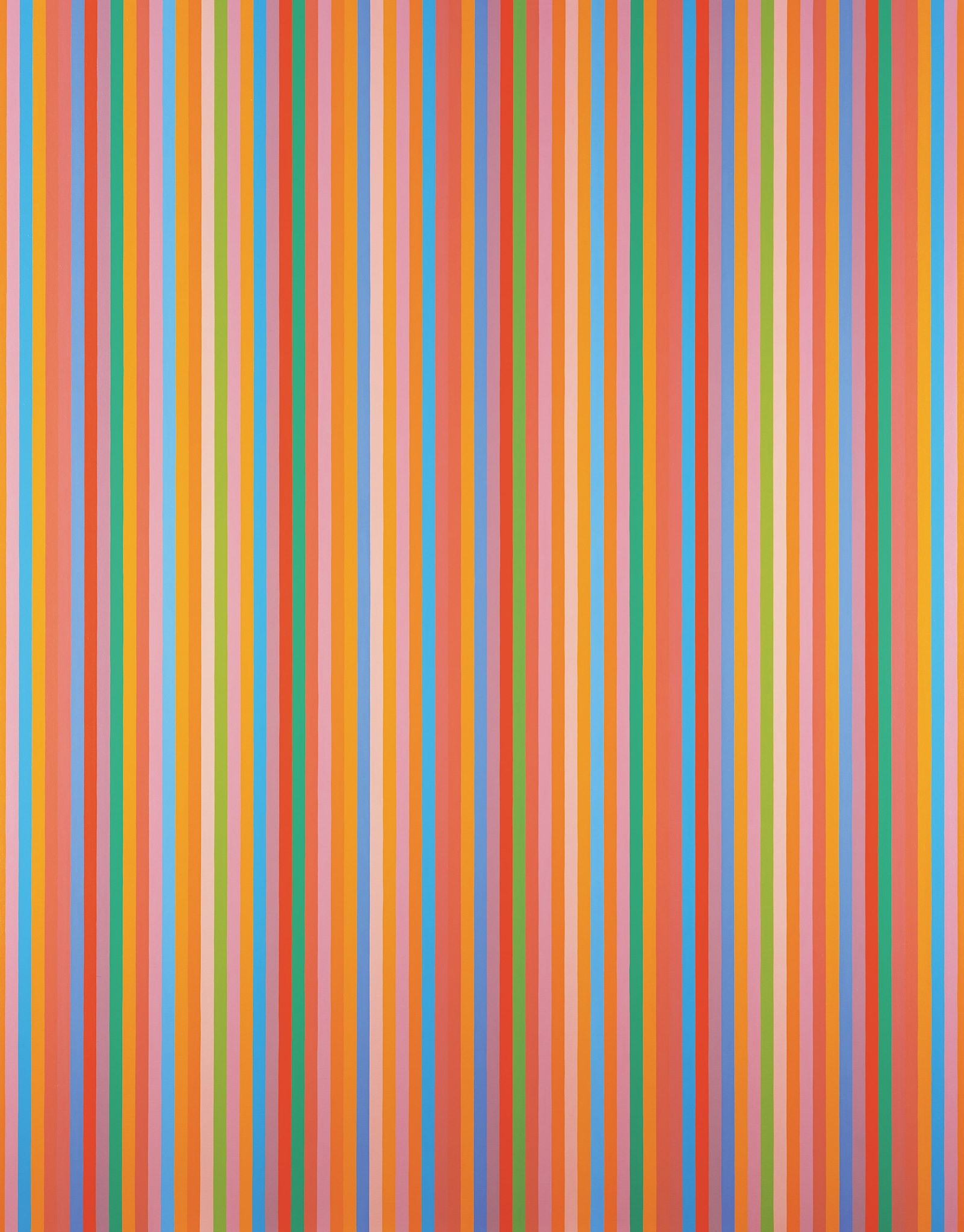

High Sky, 1991, by Bridget Riley, oil on canvas.

Aria, 2012, by Bridget Riley, oil on canvas.

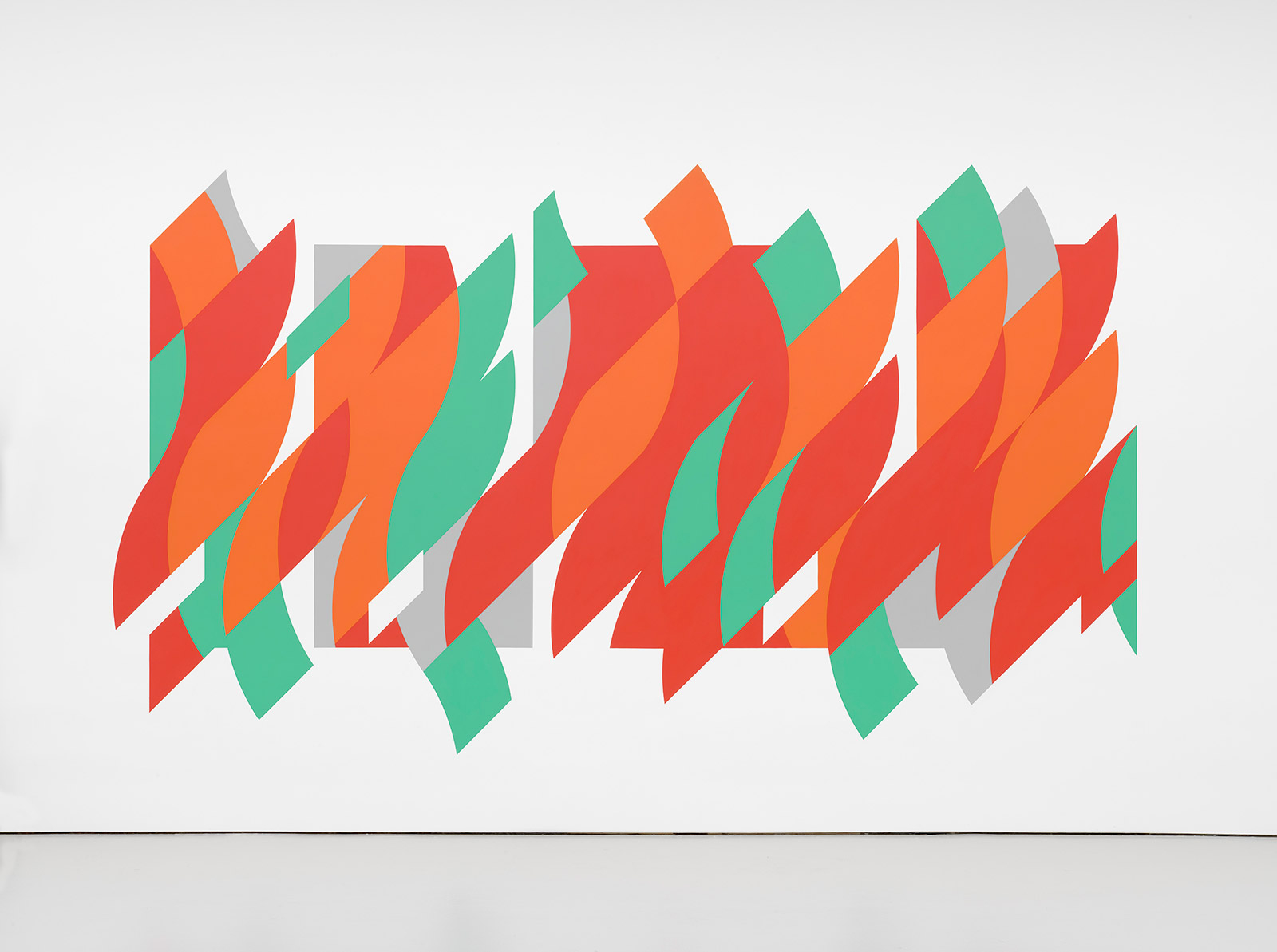

Rajasthan, 2012, by Bridget Riley, view at David Zwirner, New York, 2015. © The artist. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner.

View of ‘Bridget Riley’ at Hayward Gallery, London. © The artist.

Blaze 1, 2016, by Bridget Riley.

Quiver 3, 2014, by Bridget Riley, view at Hayward Gallery, 2019. © The artist.

INFORMATION

‘Bridget Riley’, until 26 January 2020, Hayward Gallery. southbankcentre.co.uk

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

ADDRESS

Hayward Gallery

Southbank Centre

337-338 Belvedere Road

London SE1 8XX

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.