Art or machinery? L’Art et la Machine opens in Lyon

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Since artists are often seeking to interpret quotidian life around them, it should come as no surprise that they would have been drawn to the novelty of machines right from the start of the Industrial Revolution. A new exhibition at the Musée des Confluences in Lyon, titled L’Art et la Machine, explores how the two realms overlap aesthetically and to a lesser extent, technically. From William Jackson’s ornate monocycle to Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel, the Louis Lumière’s film of an approaching train to Chris Burden’s ship models spinning around an Eiffel Tower, the show reverberates with artistic renderings of production, progress, mechanics and engineering.

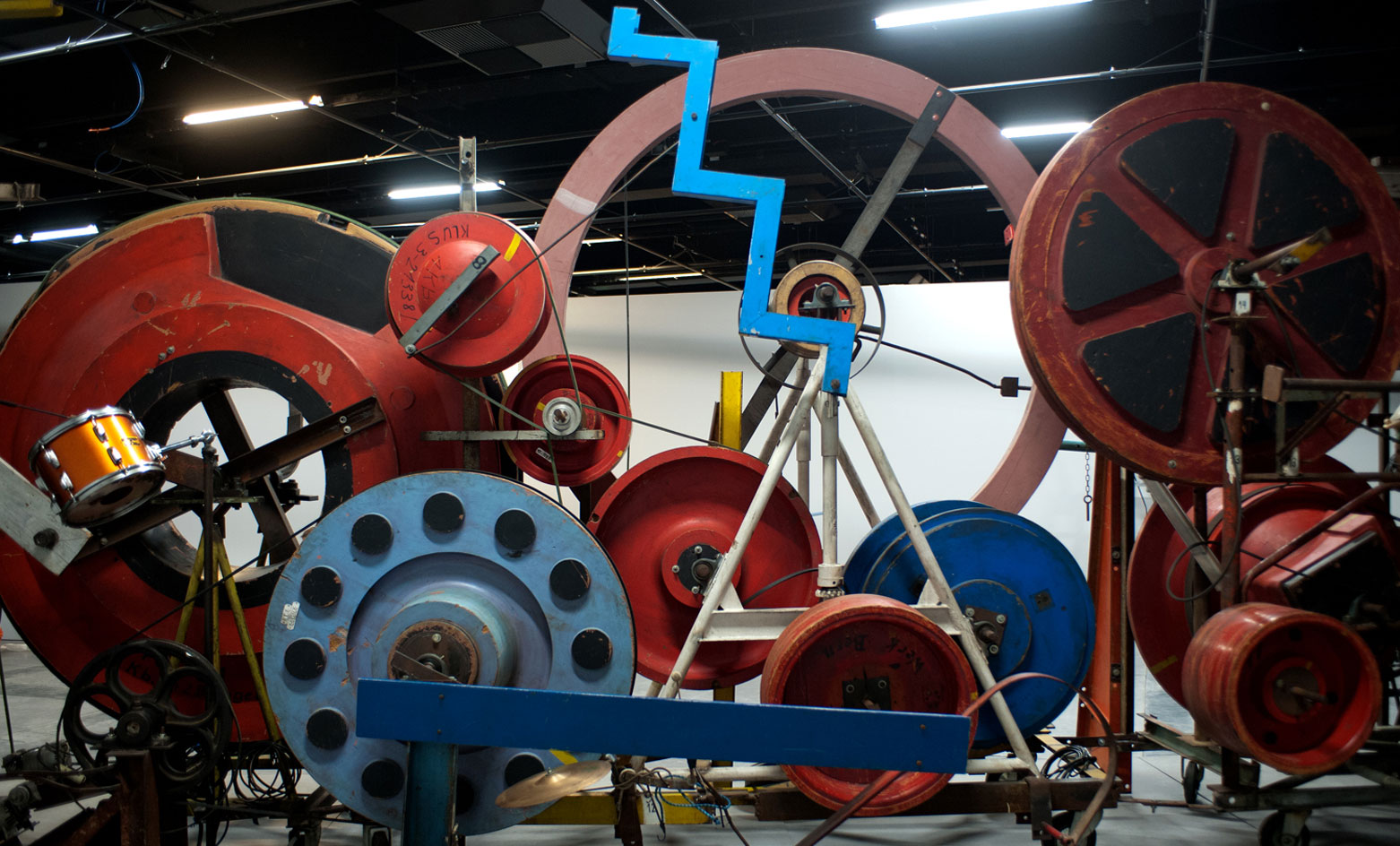

Displaying upwards of 170 works in soaring spaces completed by Coop Himmelb(l)au last December, it also poses a fundamental question concerning process; in simplistic terms, art is created, machines are invented. Except, of course, this distinction isn’t as crisply black and white as the Alfred Stieglitz and Germaine Krull’s photos of airplanes and apparatuses. Are vintage cameras, including one designed by Jean-Luc Godard, now considered objets d’art? Is Jean Tinguely’s La Cloche from 1967 a machine because its electric motor forces a bell to sound?

The idea for the exhibition dates back to 2001 when conservationist Claudine Cartier and well-known culture journalist Emmanuel de Roux published a book on industrial patrimony in France. After De Roux passed away in 2008, Henri-Claude Cousseau (former director of the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris) stepped in to co-curate the show, which largely consists of loans from institutions across Europe.

A series of genre paintings by mostly unknown nineteenth century artists depict factory workers toiling by the glow of furnaces and shouldering oversized steel parts. Arguably, the canvases serve a documentary purpose more than an aesthetic one. The next few galleries show how Fernand Léger, Robert Delaunay and Frantisek Kupka applied abstraction to capture speed. Elsewhere, César’s compressed Alfa Romeo and Arman’s fanned column of Renault R16 side panels show how parts meant for motion have been rendered as static, architectural sculptures. Perhaps inspired by the selection of films on view (Metropolis, Modern Times, Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, the Matrix), the exhibition excels in theatrical shadow play and dynamic scenography so that the darkened spaces have the ambience of a film noir set.

The final section of the show shifts gears, as contemporary art from Nam June Paik, Claude Lévêque, Bertrand Lavier and Ai Weiwei use machines as their media. Given that the works appear disassembled, crumpled, caged-in or repurposed, the statement turns from valorisation to a commentary on how we live with machines today. And now that our era has transitioned into all things digital, the pièce de résistance, Tinguely’s ambitiously oddball Méta-Maxi (1986) offers a somewhat bric-a-brac throwback to old-school assembly. On loan from the Daimler Art Collection in Stuttgart, the hulking, work of art was pieced together from factory offcuts, reclaimed debris and an assortment of neglected toys. Every few minutes, visitors can watch it rev up so that the various parts produce an amusing racket of clunks and clangour.

Titled L’Art et la Machine, the show displays 170 works in soaring spaces completed by Coop Himmelb(l)au.

The installation poses a fundamental question concerning process; in simplistic terms, art is created, machines are invented. Pictured: Le Remorqueur by Fernand Léger, 1920

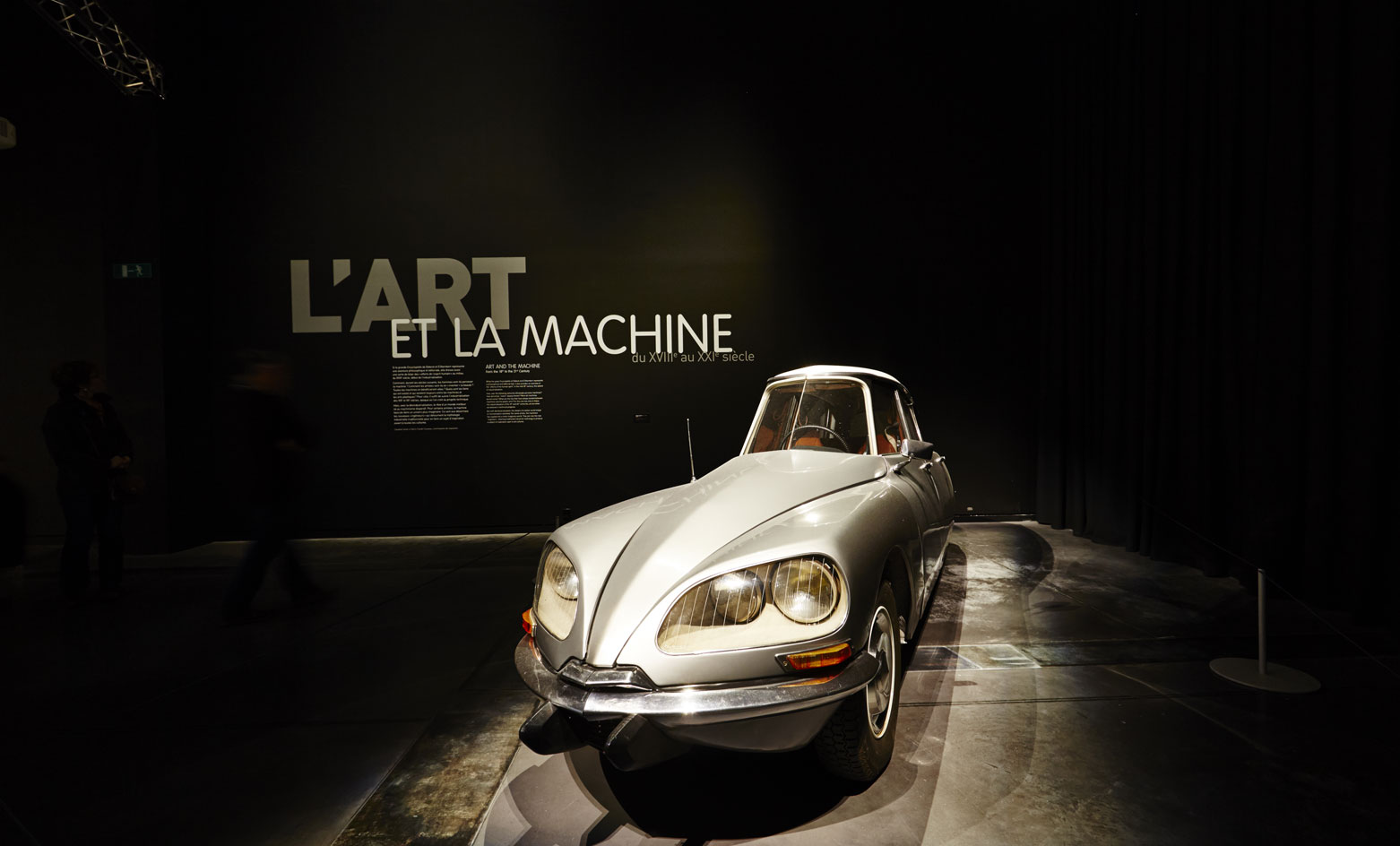

La D.S by Gabriel Orozco, 1993.

Is Jean Tinguely’s La Cloche from 1967 a machine because its electric motor forces a bell to sound? Pictured: Méta-Maxi by Jean Tinguely, 1986.

The idea for the exhibition dates back to 2001 when conservationist Claudine Cartier and well-known culture journalist Emmanuel de Roux published a book on industrial patrimony in France.

The Aeroplane by Alfred Stieglitz, 1910.

Foreground: Another World by Chris Burden, 1992.

INFORMATION

’L’Art et la Machine’ is on view till 24 January 2016. For more information, visit the website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.