At home with Calder: the artist’s hidden knack for domestic design

In September 1933, Alexander Calder and his wife Louisa purchased a property in Roxbury, northwest Connecticut. This 1760 farmhouse became the artist’s long-time home and studio: the American sculptor constantly adapted it to fit his growing family and built three studios over the years to accommodate his practice. ‘Roxbury had a direct impact on Calder’s work. He owned 18 acres and was inspired to bring sculpting outdoors for the first time,’ explains Alexander SC Rower, president of the Calder Foundation and grandson of the artist.

It was here in the expanse of Roxbury’s rolling hills that Calder created many seminal pieces, including Apple Monster (1938), made from a fallen branch of an ancient apple tree on the property. After being exhibited all over the world in countless blue-chip galleries and museums, the prolific 20th-century artist’s works are returning to their natural setting in a bucolic landscape, albeit as part of a major solo exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, the Swiss gallery’s rural English outpost.

Installation view of ‘Alexander Calder. From the Stony River to the Sky’ at Hauser & Wirth Somerset.

The show focuses largely on the hanging and standing mobiles that Calder was renowned for, presented alongside stabiles, oil paintings, works on paper, jewellery, and monumental outdoor sculptures set within the Piet Oudolf-designed gardens. The exhibition takes its title from the etymology of the surname Calder in Celtic – meaning ‘from the stony river’ – and its inspiration from the artist’s Connecticut residence.

Calder’s less celebrated penchant for design, however, is the real revelation here. Occupying two galleries in the Somerset exhibition is a ‘tremendous installation’ of handcrafted domestic objects and ‘household works’. ‘I say “works’,’ explains Rower, ‘because they’re not works of art but yet they’re works of intriguing significance.’ The remarkable display of the artist’s furniture and product design – plucked from the Roxbury home – includes a chess set, chairs, a coffee table, a pepper grinder, ashtrays, candle holders, a silver rattle, and even a rug designed by Calder and hooked (and subsequently cosigned) by Louisa.

Calder-designed sculptures, ashtrays and candleholders on display at Hauser & Wirth Somerset.

The artist tinkered relentlessly with objects in and around his home, creating endless iterations of humble domestic objects – and no two were ever the same. ‘Sometimes [Calder] challenges you to understand whether it’s a work of art, or a work of decoration, or a utilitarian object,’ says Rower. There was an instance, he recounts, where his grandfather destroyed a perfectly fine Tiffany vessel to harvest the sterling silver, fashioning it into a teething rattle for Calder’s daughter (and Rower’s aunt) Sandra.

‘He converted undistinguished porcelain teacups – inherited from his parents – into espresso cups by adding brass wire ornamental holders (known as zarfs) to insulate fingertips from the searing porcelain. Eventually, he reimagined the entire ceremony of freshly brewed coffee, making or improving everything that was required,’ says Rower. ‘Throughout his life, my grandfather continued to reimagine the purpose of items otherwise relegated to obscurity.’

Here, we trace the provenance of five more domestic objects handcrafted by Calder...

Chess set, c1933, wood and paint

‘Calder was very close with Marcel Duchamp and made a whole array of different chess sets,’ says Rower. In the Somerset show, the chess set has been laid out as a Duchamp game from 1931, depicting ‘move 32 in a game of 41 moves’.

Calder Foundation, New York; Mary Calder Rower Bequest, 2011.

Dinner bell, 1942, glass and wire

‘This was a cheap Mexican goblet wine glass and the stem broke off at party,’ explains Rower. ‘Instead of throwing it away, he repurposed it and turned it into a dinner bell, which is an amazing thing. It was actually used, they used it all the time. These weren’t special occasions – this is just how they lived.’

Toilet paper holder, c1952, wire and sheet metal

Calder built his mother a house on the Roxbury property after his father passed away. ‘His father was a sculptor and his mother was a painter, and they were very close,’ says Rower. ‘ He built her this little house to move into, and in the bathroom he attached to the windowsill this hand as a toilet paper holder, to unfurl the toilet paper.’ An accompanying bathroom mirror was designed at the same time.

Toaster, c1942, wire, wood, metal, plaster, nails, and screws

According to Jessica Holmes, art critic and former deputy director of the Calder Foundation: ‘Calder believed his visualisation of a toaster was stronger than that of a mass-produced one, which led him to develop toasters of his own conception. One design (pictured below) includes an ingenious “warming plate” upon which toasted slices of bread could rest, melting the butter via the heat generated by the machine below.’

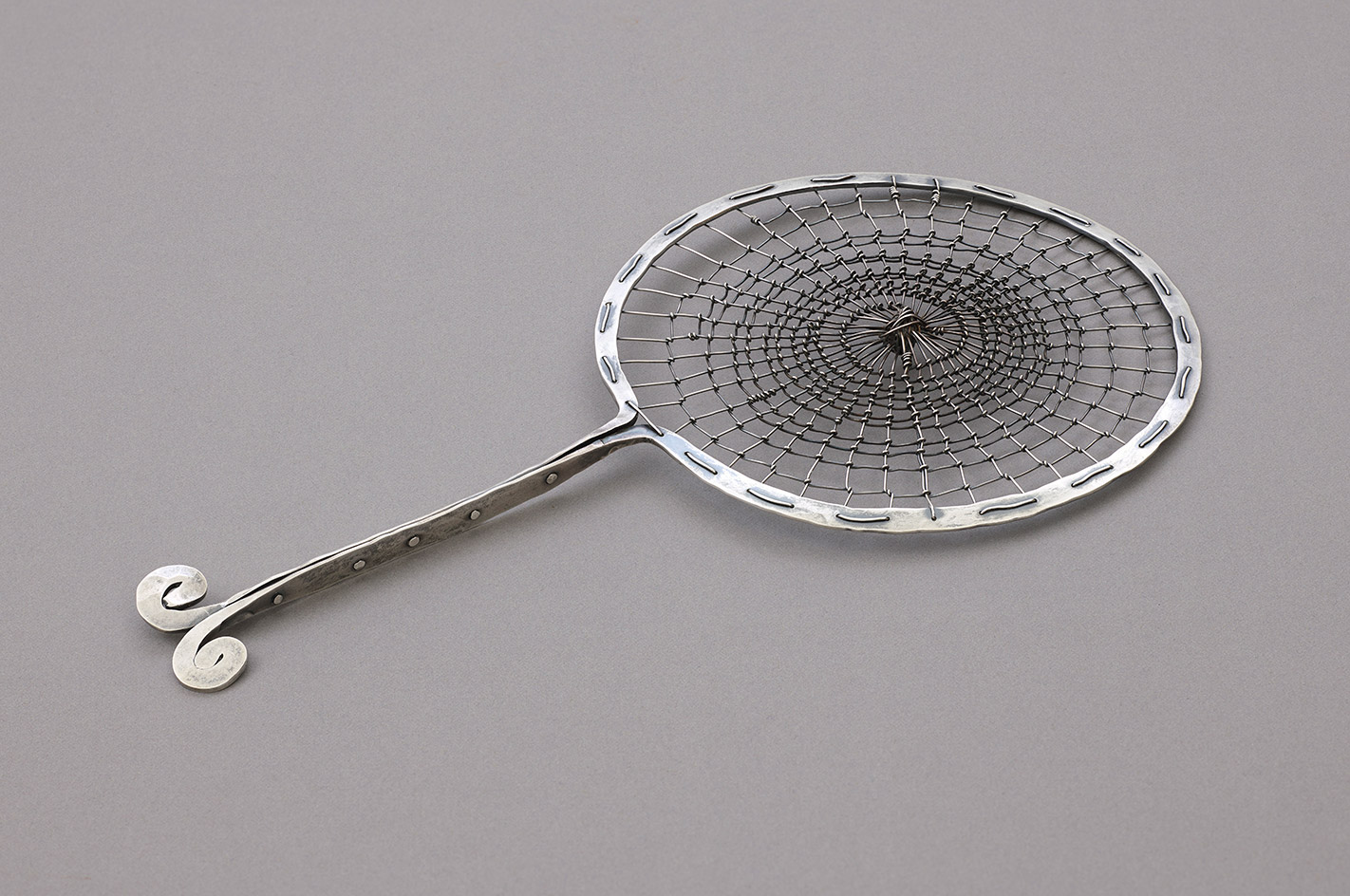

Milk skimmer, c1940, silver wire

‘This exotic object is for the kitchen. When my grandparents went to the farm down the road to get a bucket of fresh milk, they would boil it on the stove to pasteurise it,’ adds Rower. ‘You put this [skimmer] into the pot and lift that leathery skin off it. It’s also made from silver – bacteria doesn’t grow on the surface of silver.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

INFORMATION

‘From the Stony River to the Sky’ is on view until 9 September. For more information, visit the Hauser & Wirth website

ADDRESS

Hauser & Wirth Somerset

Durslade Farm

Dropping Ln

Bruton BA10 0NL