Touring St Petersburg’s New Holland Island and its ongoing transformation

New Holland Island is a historic artificial island in Saint Petersburg, Russia, dating from the 18th century. Now, under an architect's guidance, development continues apace, transforming it into a vibrant cultural hub

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

St Petersburg is ‘built on bones', locals say. A swampy estuary marsh of the 18th century settlement founded by Tsar Peter the Great became the modern city of today – and Europe's third largest – thanks to the toil of thousands of conscripted convicts, dissidents and prisoners of war, who were left to dig with their hands and carry the mud in the folds of their shirts. The trunks of countless trees lie in layers beneath the paved streets of today; the ground was too boggy and wet for anything to be built upon.

St Petersburg was designed to be a Janus-faced place, both the ‘window to Europe' and a fortress designed to protect Mother Russia from further Western encroachment. This is reflected in the carefully-organised complex of straight-line canals that emanate out from a fortified centre – a facsimile of the Western cities Peter visited on his travels. It’s often called The Venice of The North, but Peter was in fact inspired to create a grander, more monumental version of Amsterdam, the Dutch city in which he spent his youth working in a ship-building yard.

From this perspective, perhaps the most contemporary aspect of modern St Petersburg can be understood as a microcosm of this history. If one walks east along the banks of the Neva from the Hermitage museum, you will soon find Novaya Gollandiya – which translates, literally, as New Holland.

Whilst Moscow has always trumpeted Gorky Park, St Petersburg has never had a public, open and accessible park-space. But now, at New Holland Island, amidst the billowing skies and moody waters and grey stone, one can now find Russians from all walks of life reclining on deckchairs or arranging their picnics on the grass of this 19-acre modern oasis, nestled between the Moika river and the Kryukov and Admiralteisky canals, and offering a countless array of restaurants and shopping boutiques, exhibition and performances spaces, carefully manicured gardens and children’s play areas.

A history of New Holland

New Holland Island began life in 1719 as a military base; a garrison for the Russian navy. Separated from the mainland in 1730, it was designed to protect the city against water-based invaders, and to be an engine-room for Peter the Great’s fleet of ships.

The site was abandoned after the fall of the USSR. Modern redevelopment began after a €400 million investment from Millhouse LLC, an asset management company owned by Russian oligarch and Chelsea football club owner Roman Abramovich, in 2010. It is now owned and administered by Millhouse LLC in cooperation with the Iris Foundation, an initiative set up by Darya Zhukova, Abramovich’s former wife and founder of the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow. The island reopened to the public in a limited capacity in August 2011, before becoming an all-year-round public space in the summer of 2016.

The development continues apace. The park has, this summer, also launched a performance space which is largely free to attend. Over the course of this year, visitors to New Holland have enjoyed an almost nightly programme of concerts, including a recent performance by Charlotte Gainsbourg, alongside theatre, ballet and dance productions. The space also plays host to three separate film festivals, numerous art exhibitions and installations, DJ sets and a regular vinyl market.

It’s the unique historical context that creates the extraordinary atmosphere of this place.

Although dilapidated and fallen into disrepair, the buildings of New Holland were granted UNESCO heritage status for their historical significance. As such, each building has had to be carefully restored. To do so, New York-based firm WORKac were originally consulted to build the masterplan, known for its work on Manhattan’s High Line, whilst the Dutch landscape architecture firm West 8 was recruited to restore the island’s grounds. Latterly, the redevelopment has been primarily overseen by young St Petersburg-based architects Sergey Bukin and Lyubov Leontieva of Ludi Architects.

An architects' view

In an interview, Lyubov Leontieva says the renovation project has required some creative thinking. ‘It’s the unique historical context that creates the extraordinary atmosphere of this place and has always made it so incredibly distinctive,' she says. ‘This, I think, gives rise to innovative planning and design solutions, so in the end those challenges were the reason behind some great architectural and design ideas.'

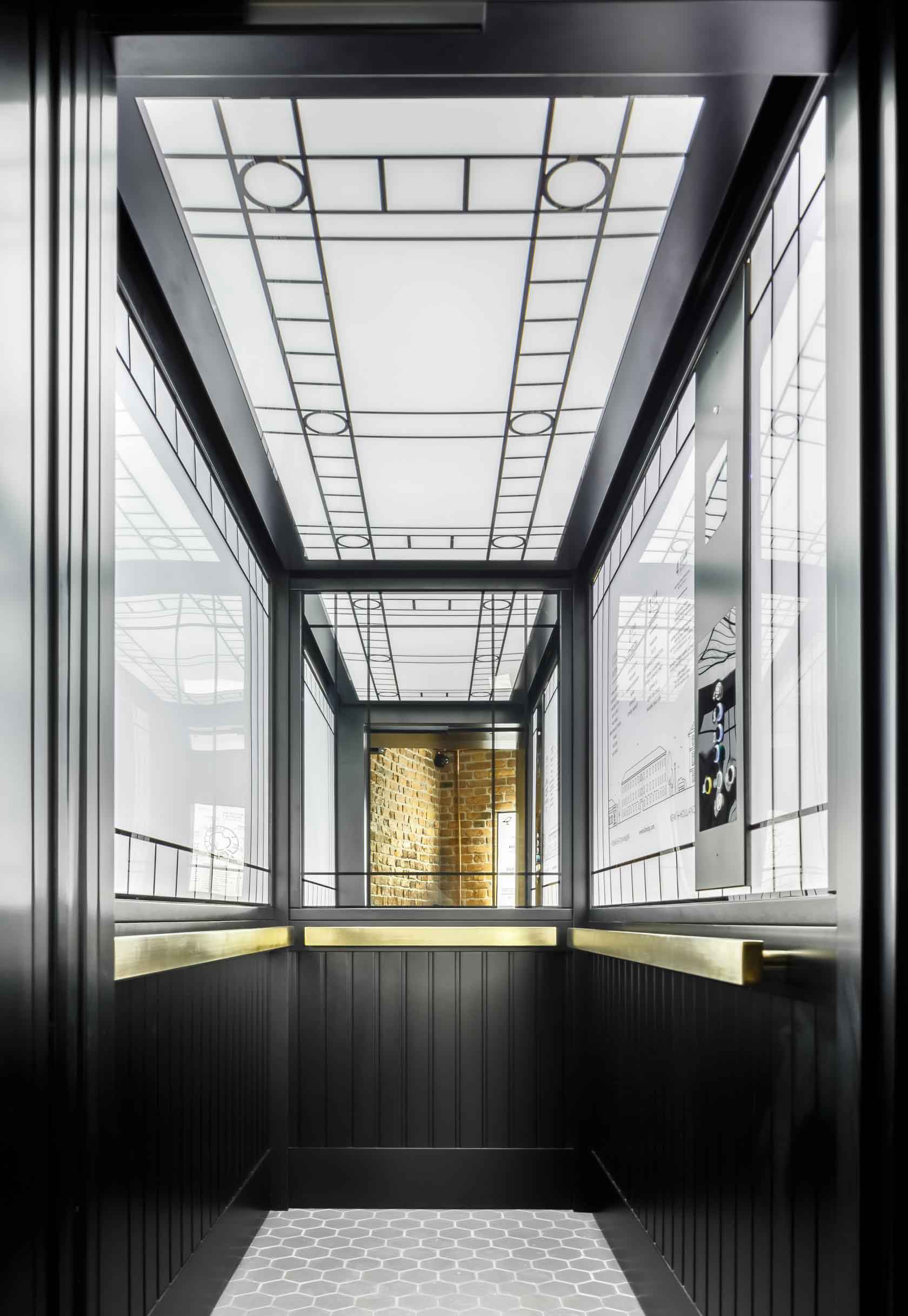

Each of the six major buildings has come with its own unique set of challenges. ‘Every building has a unique interior,' Leontieva says, ‘but there are certain design elements, textures and shapes, that echo one another and create the feeling of symbolic and stylistic connections between them'.

Leontieva’s work has not gone unnoticed. In 2018, New Holland was awarded with the Bernhard Remmers Academy award from the European Institute for the Conservation and Maintenance of Historic Buildings in the category Best International Project.

New Holland’s ship-building lineage is visible via the immensity of the red-brick barracks and warehouses that still stand on the northernmost side of the of the island; each are tall enough to store a ship’s mast standing upright. The whir of machinery is audible from within the barracks; whilst the island’s three smaller buildings – the Foundry, the Commandant’s House and the Bottle House – have all been successfully restored and re-opened, the larger barracks are scheduled for public perusal at some point in the mid 2020s.

The Island is a continuous work in progress. It has come to represent the rich and multidimensional culture of the city it was built in.

Although painstaking work, Leontieva welcomes the opportunity to bring life back to buildings that form part of the city’s past. Linking two of the barracks is a grand, Roman-inspired segmental arch, named the Arch of Vallin de la Mothe. Leontieva calls it: ‘one of the symbols of St. Petersburg'.

‘The idea that it could be dismantled for the sake of some modern building of questionable architecture seems totally preposterous', she says. ‘On the contrary, it is our great fortune that we can offer people the opportunity to enjoy the historical buildings that have no analogues in St. Petersburg or anywhere else in Russia.'

To the south is a grand circular building known as the Bottle House, given its resemblance to a bottleneck. In its centre stands a theatre in the round, where, on a nightly basis, performances are staged for free. Walk along its curved interiors and one will find Israeli, Vietnamese, Georgian and Mexican restaurants on the ground floor, fashion and art boutiques, a bookshop curated by Zhukova’s Garage, and ballet, boxing and spa facilities on the top floor. What, one wonders, would the original residents of The Bottle House make of its 2019 iteration, once a naval prison.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

What does the future hold for New Holland?

History presses on this city. On a boat-ride, our tour guide casually points out the former homes and hang-outs of Alexander Pushkin, Karl Fabergé, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Pyotr Tchaikovsky, Dmitri Shostakovich and Alexander Rodchenko. So too does history press on New Holland Island. At the heart of the island lies a large water basin on which large artificial waterlilies float and art installations emit strange, digitised noises. In the winter, it doubles as an ice-rink. Yet the basin was where the USSR’s globally-feared submarines were developed and tested.

‘The Island is a continuous work in progress', Leontieva says. ‘Yet it has come to represent the rich and multidimensional culture of the city it was built in'. If one looks carefully amidst the high-end shops, art installations, deck-chairs and cafes, one can find the spot where Lenin first broadcast the onset of the Russian revolution. The revolution may not be continuing quite as he had in mind, but New Holland suggests St Petersburg retains a powerful global position.

INFORMATION

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.