Take a tour of the 'architectural kingdom' of Japan

Japan's Seto Inland Sea offers some of the finest architecture in the country – we tour its rich selection of contemporary buildings by some of the industry's biggest names

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The Seto Inland Sea in Japan, nestled between the Hiroshima, Okayama, Hyogo, Kagawa and Ehime prefectures that form the Seto Inland region, is a treasure trove of 20th and 21st-century architecture gems. This is not only the result of the local architects' inspiring visions. It also stands as testament to a series of clients with a forward-thinking stance and deep ambition – a confluence that created the perfect breeding grounds for pioneering building design.

Join our architecture tour to find out more.

Seto Inland Sea: context and origins

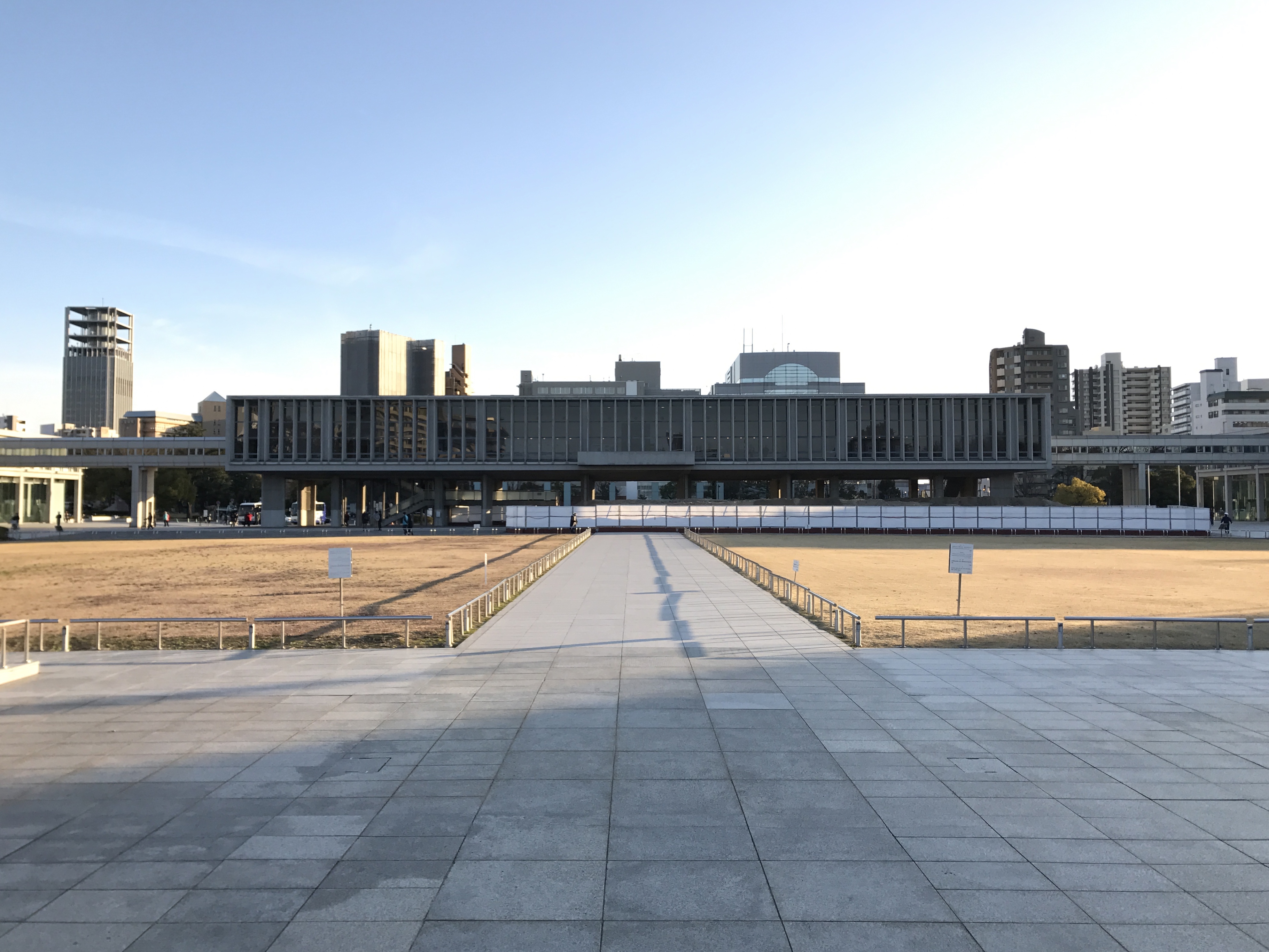

The emergence of avant-garde post-war architecture in the Seto Inland region owes much to the presence of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, built by Metabolist architect Kenzo Tange in 1955. Commissioned by the state to mourn the victims of the nuclear attack, the institution was designed by Tange, a native of Ehime Prefecture's Shikoku island, which faces the Seto Inland Sea.

Mount Washu - Looking at the Seto Inland Sea

Instead of Japan's traditional timber frame style, it was constructed using concrete, a cutting edge material for the time.

'Tange applied the Japanese-specific timber construction method, built with columns and beams, to concrete used in Western structures. This method spread throughout Japan,' says Terunobu Fujimori, an architectural historian who interviewed Tange during the architect's lifetime. The technique is particularly evident in the Seto Inland region's buildings.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

There was plenty to build following the destruction of WWII. Kagawa Prefecture suffered particularly from air raids by US bombers. In Takamatsu City alone, 73 public buildings were destroyed, including the prefectural office, 264 factories and companies, and 90 temples and shrines.

Politicians and local business leaders wanted new public buildings that would be cherished by all and that would demonstrate the ideals of Japan's newly-formed democracy. The charge was led by Masanori Kaneko, who served as Governor of Kagawa Prefecture for 24 years. Guided by the conviction that ‘politics and art are one and integrated as a whole. Both must be dedicated to enriching the life of the citizens,’ Governor Kaneko commissioned the construction of several civic buildings and cultural facilities, which earned him his nickname, ‘design governor’.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The result is one of the richest assortments of architecture in Japan, by some of the world's leading design names. Here are eight highlights from the Seto Inland Sea region.

8 buildings to see around Japan's Seto Inland Sea

Kagawa Prefectural Office, Kagawa Prefecture

Architect: Kenzo Tange

Year: 1958

The Kagawa Prefectural Government Building was designed by Kenzo Tange (1913–2005), who was deeply influenced by Le Corbusier and practised with the latter's disciple, Kunio Maekawa. The building incorporates traditional Japanese design elements – such as columns and beams reminiscent of timber construction, and balconies with handrails – but uses concrete, just as he did at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Responding to then-Governor Kaneko's request for ‘an civic building befitting the democratic age,’ Tange conceived a ‘prefectural office open to the citizens.’ This spirit is most strikingly embodied in the ground floor's pilotis – a column-supported, wall-less atrium. The pilotis created a dramatic, publicly accessible space that allowed free passage for all citizens who might not otherwise have ventured in.

Interior of The East office of Kagawa Prefecture

The ceiling features wooden louvres made from local pine timber, while the floor incorporates paving stones of Aji stone and Shodo island granite (both found nearby), alongside pebbles collected from the ocean floor. Tange's distinctive design, blending Japanese and Western elements, remains a powerful statement today.

Seto Inland Sea History and Folklore Museum, Kagawa Prefecture

Exterior of the Seto Inland Sea History and Folklore Museum in Goshikidai

Architect: Tadashi Yamamoto

Year: 1973

Perched atop the Goshikidai hills overlooking the waters between Okayama and Kagawa Prefectures, the Seto Inland Sea History and Folklore Museum is a facility conceived to convey the life and culture of the region. It displays fishing gear, wood boats and domestic items from the area. The stone-built structure was designed to harmonise with the natural surroundings by architect Tadashi Yamamoto (1923–98), who was also an official at the Kagawa Prefectural Government.

During his tenure at the prefectural office, Yamamoto nurtured his architectural philosophy through collaborations and exchanges with figures such as Tange, artist Isamu Noguchi and designer George Nakashima through which he was exposed to a new wave of post-war modernist design. The stone-piled exterior, made from the volcanic rock andesite, evokes a pirate's castle. The stone-piling was overseen by Masatoshi Izumi, a stone sculptor and production partner of Noguchi, who had a workshop in Kagawa. The concrete walls were built using formwork techniques to reveal wood grain patterns, blending naturally into the hilly landscape of Goshikidai.

Teshima Art Museum, Kagawa Prefecture

Teshima Art Museum within the green land

Architect: Ryue Nishizawa and Rei Naito

Year: 2010

Perched on a hill near Karato Port in Teshima – an island between Shodoshima and Naoshima in the Seto Inland Sea – the Teshima Art Museum is a collaborative work by architect Ryue Nishizawa and artist Rei Naito. Built on a section of land where terraced rice fields, once left fallow, were regenerated with the help of the locals, the architecture evokes an image of a water droplet. Measuring 40 metres along its short side and 60 metres in length, with a maximum height of 4.5 metres, the building is a concrete shell structure without a single pillar. Its smooth volume, made of free-form curves, appears to merge seamlessly with the surrounding terrain.

Integrated with this architecture is Rei Naito's installation work ‘Matrix’, which explores the animating force (anima) of nature. This piece incorporates an underground spring and throughout the day, water emerges from numerous points on the floor, creating a fountain. Surrounding sounds of nature, light, wind, and rain come through the two openings above, creating a space where environment – which changes seasonally – art and architecture are integrated.

Inujima Seirensho Art Museum, Okayama Prefecture

Inujima Seirensho Art Museum

Architect: Hiroshi Sambuichi

Year: 2008

The Inujima Seirensho Art Museum – approximately a ten-minute cruise ride from Hoden Port on mainland Okayama prefecture – is a museum centred on the theme of ‘heritage, architecture, art, and environment.’ It was created by renovating a copper smelter that operated for only ten years from 1909 before falling into disuse. The environmentally conscious architecture, conceived by Hiroshima-based architect Hiroshi Sambuichi, incorporates existing chimneys and Karami bricks – slag bricks made from the residue left after copper is removed during the smelting process – while utilising natural energy sources like solar and geothermal power.

The museum incorporates an advanced water purification system harnessing the power of surrounding plants, evolving like a living organism as part of Inujima's perpetual natural cycle. Art works evoking the spirit of novelist Yukio Mishima, who rang a wakeup call to Japan's rapid modernisation, fill the space which once contributed to the country's industrial evolution but now exists only as a shadow trace – making a comment about the future of the country and its relationship to its past through art and architecture.

Kurashiki International Hotel, Okayama Prefecture

Architect: Shitaro Urabe

Year: 1963

Opened in 1963, the Kurashiki International Hotel is as popular now as when it first launched. Founded in response to growing post-war calls from local businesses and the government for an international-standard hotel in Kurashiki, a local city in Okayama prefecture, the hotel was born from the vision of its founder, Ohara Soichiro, who sought to create a modest but practical establishment where heartfelt hospitality prevailed.

When architect Shintaro Urabe (1909–1991) designed the building, he intended it to blend into Kurashiki’s landscape. Constructed in reinforced concrete, it was conceived as a fusion of Japanese and Western styles. The traditional namako kabe – a type of wall in coloured tiles found in Kurashiki’s historical district – appears alongside pitched kabe hisashi eaves, resembling mini roofs, which are layered on top of each other across all floors and nod to local construction typologies. Urabe’s vision described that, ‘by the time the ginkgo trees planted by the hotel at its opening have grown into spreading trees, this hotel too will have put down deep, strong roots in local and among the people of Kurashiki, welcoming visitors from around the world.’

Elements like the staircases, handrails, and wall clocks remain unchanged since the hotel's opening. Urabe, while planning the design, sat with the hotel's general manager, gaining deep insight into how the hotel might operate – such as the importance of maintaining the line of sight for guests seated in the lobby and how international guests spend their time in their rooms. This resulted in his meticulous detailing of the interior. The hotel is a source of pride for the local citizens of Kurashiki, and a piece of architecture that is truly embedded in the local life.

Honpukuji Temple, The Water Temple, Hyogo Prefecture

Architect: Tadao Ando

Year: 1991

One of the Buddhist Shingon sect’s temples, Honpukuji, dating back to the 12th century, is located on Awaji Island in Hyogo Prefecture, overlooking Osaka Bay. Enshrined here is a statue of Yakushi Nyorai, which is also designated an Important Cultural Property. In 1991, Tadao Ando designed the new main hall, Mizumido – Water Temple – to honour this deity. Accessed by a wooden approach leading to the new main hall, Ando’s temple is not something one would expect from an ordinary Japanese temple: an austere concrete wall divides the secular world from the sacred realm.

Circling it to enter, visitors encounter a 40m long elliptical pond cast in concrete. Floating within are water lilies, a Buddhist symbol. A staircase leading underground is positioned centrally, bisecting the lotus pond. Descending these steps, as if burrowing beneath the earth, leads to the main hall. In the late afternoon, when the sunlight streams in from the west and layers different colours on the vermilion-painted walls, the hall is bathed in a tapestry of crimson hues, offering visitors a unique experience where time and space seem to merge.

Yodogo Geihinkan, Hyogo Prefecture

Posted by YodokoGeihinkan on

Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright

Year: 1924

In 1924, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) designed this residence for Taizaemon Yamamura, a local who ran a sake brewery. Shortly after the Second World War, it became the property of Yodogawa Steel Works Co., Ltd., and has been open to the public since 1989. Wright undertook the original design in 1918, but soon returned to America, so completion was entrusted to his disciples in Japan, Arata Endo (1889–1951) and Makoto Minami (1892–1951). Following Wright's exploration of the fusion of nature and architecture, the architecture exploited the site's undulating terrain, extending from the nearby Rokko Mountains, and the floors are arranged in a stepped configuration running north-south.

A notable feature is the 120 small windows arranged throughout the house, which allow natural light to filter through during different hours of the day, creating an ever-changing interior atmosphere. The use of sculpted Oya stone is another unique and unusual element. The material is commonly used for exteriors, but here, it features expansively in the interior. Oya stone sourced from Oya town in Tochigi Prefecture is soft and easy to work with, and was a favourite material for Wright when he worked on the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo.

Kiro-san Observatory, Ehime Prefecture

A post shared by JAPAN🇯🇵TRIP (@japantrip55)

A photo posted by on

Architect: Kengo Kuma and Associates

Year: 1994

Kiro-san Observatory crowns the 307.8 metres-high Kiro mountain Observatory Park in Ōshima in Ehime Prefecture. As Oshima is among more than 700 islands dotted around the Seto Inland Sea, the site commands panoramic views of the world's first triple suspension bridge, one of Japan's three major tidal currents, as well as the highest peak in western Japan – Mount Ishizuchi – when the weather is clear. However, as the site sits within the Kiro-san Observatory Park, part of the Seto Inland Sea National Park, regulations prevented the construction of a conventional protruding structure that might unduly spoil the mountain scenery.

Kengo Kuma, whose studio designed the Observatory, says, ‘We attempted to make architecture disappear on the summit of Ōshima’. Avoiding the fate of conventional protruding observatories – where the act of construction distracts from the landscape – Kiro-san Observatory is instead folded into its environment. Its structure is buried within the terrain, forming an observation deck that remains imperceptible from the outside while offering views from within.