Utopian, modular, futuristic: was Japanese Metabolism architecture's raddest movement?

We take a deep dive into Japanese Metabolism, the pioneering and relatively short-lived 20th-century architecture movement with a worldwide impact; explore our ultimate guide

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

'We regard human society as a vital process – a continuous development from atom to nebula.' These powerful words were not only ingrained into the punchy opening paragraph of a 90-page manifesto handed out at the World Design Conference in Tokyo in 1960 – they also sparked the official emergence of one of Japan’s most radical architectural movements: Metabolism.

What is Japanese Metabolism?

Futuristic, modular, organic, experimental and always in flux – Metabolism was a utopian post-war Japanese movement that reimagined cities and their structures as flexible, growing, adaptable systems, inspired by living organisms.

A Nakagin Capsule Tower pod interior, as seen at MoMA's show

The origins of Japanese Metabolism

Metabolism’s genesis as an architectural tool for social change was defined by the times. It was in the 1950s that the seeds of the movement were first planted amid the ashes of Japan’s widespread post-war urban annihilation and subsequent renaissance.

As Japan’s recovery journey gathered pace, a string of young architects in Tokyo – including Kisho Kurokawa, Fumihiko Maki, Kiyonori Kikutake – were deeply drawn to explorations of flexible, modular and organic urban design, with inspiration rooted in biology, technology and futurism.

Soon after, Japan was on the brink of enormous economic growth. A few years later, in 1964, Japan hosted the Tokyo Olympics and launched its first shinkansen bullet trains – a seminal moment that confirmed to the world its reinvention from war-hit nation to global leader. Added to the mix was a rapidly growing population – all combining to create the perfect conditions for questioning how to reorganise a fast-evolving urban society for the future.

At the same time, ideas of renewal and impermanence have also long been timelessly ingrained across traditional Japanese culture – from its Zen Buddhist philosophies and aesthetics to its ritual of rebuilding Ise-Jingu, one of Japan’s most important shrines, every 20 years.

Key representatives

Kagawa Prefectural Gymnasium, Kenzo Tange's modernist gymnasium known as the 'ship gymnasium' in Japan, a curved concrete structure currently under threat of demolition due to neglect

It’s no coincidence that the initiators of Metabolism were students of Kenzo Tange, the country's legendary modernist architecture master. They drew deep inspiration from Tange’s vision of large-scale urban planning and clean-lined structural clarity – although the Metabolist movement challenged the uniformity of the International Style, the standardised modernist approach that was popular worldwide at that time.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Core ideas

Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist's launched a book on the movement in 2011, titled 'Project Japan, Metabolism Talks'

Metabolism embraced polar contrasts – the modular and the monumental, the flexible and the fixed, the technical and the human – all bound by the idea of renewal, just like living organisms, as reflected in the movement’s name in Japanese: shinchintaisha, which literally means the replacement of old with new.

From Japan, to the world

The iconic Nakagin Capsule Tower had been in danger of demolition for decades, as we reported in 2020 - it has now been demolished

The metabolists' collective ideas were crystallised into Metabolism: The Proposals for New Urbanism, a radical inaugural manifesto presented to an international design community in Tokyo in 1960, stating: 'The reason why we use such a biological word, metabolism, is that we believe design and technology should be a denotation of human society. We are not going to accept metabolism as a natural process, but try to encourage active metabolic development of our society through our proposals.'

Critically, among the 227-strong audience were reportedly 84 visitors from overseas: an impressive roll call of creatives including Louis Khan, Ralph Erskine and Jean Prouvé, among others, whose presence was instrumental in sparking cross-cultural perspectives and spreading Metabolist ideas to a wider global audience.

The seminal 1960 Tokyo conference launch paved the way for decades of playful innovations – the theoretical, the imagined and the conceptual and even, at times, the realised (although many ideas remained unbuilt). The movement peaked in productivity in the 60s and 70s, with a raft of projects brought to life.

Highlighted project

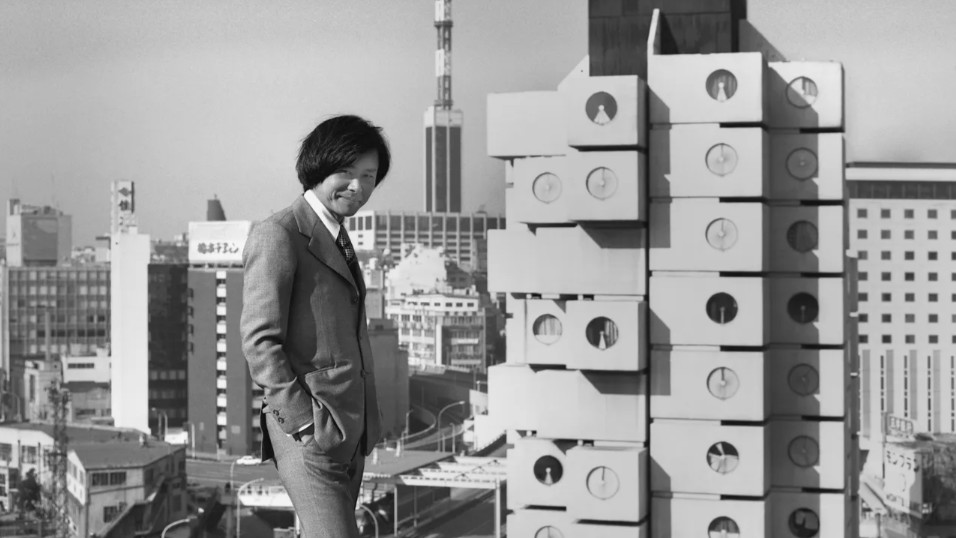

Kishō Kurokawa and his modular Nakagin Capsule Tower, both highlighted recently at a new show at MoMA, New York

Nakagin Capsule Tower is a key protagonist. The 1972 landmark was created in Tokyo’s Ginza district by Kisho Kurokawa, one of the most important figures of the Metabolist movement – who launched the project with the words: 'This building is not an apartment house.'

Its dynamic form was rooted in two concrete towers attached at the base, reaching up to 13 storeys high. Attached to these were 140 prefabricated capsules, used as single-occupancy homes or offices – each one modular, futuristic, replaceable. One of the first (and among the last surviving) examples of Metabolist architecture, the iconic tower was demolished in 2022 after falling into a state of disrepair (a number of capsules have been preserved by establishments across the world – including MoMA).

Metabolism: key examples, built and unbuilt

Sky House, 1958

A post shared by HAUS of T (@haus_oft)

A photo posted by on

An open-plan, flexible residence in Tokyo, created by Kiyonori Kikutake in 1958.

Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Centre, 1967

The Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center, premises of the Shizuoka Shimbun newspaper company, recently completed in Tokyo, Japan, 7th November 1967. It was designed by architect Kenzo Tange.

Designed by Kenzo Tange In 1967, a modular office building on an expansive scale – which still stands in the Ginza district of Tokyo

Osaka Expo ’70, 1970

Osaka, Japan: A general view of final construction stage of part of Expo '70. At right is the Rainbow Tower-the Japan Monopoly Corporation's exhibit.

This event emerged as an experimental playground for Metabolist exploration, with Tange in charge of master planning, alongside pavilions embodying ideas of flexible, mega-scale urban environments dreamt up by Metabolists, including Kikutake and Kurokawa.

Hillside Terrace, 1973

A still-popular modular housing, cultural and commercial complex by Fumihiko Maki (one of his early works) in the Daikanyama district of Tokyo that has evolved timelessly over three decades, adjusting to shifting social needs – with a flexible and layered design integrated into its setting.

City in the Air, unbuilt

A post shared by Angel Muñiz (@areasvellas)

A photo posted by on

In 1962, Pritzker Prize-winning Arata Isozaki dreamt up a futurist master plan with a dystopian edge known as City in the Air for the Shinjuku district of Tokyo, consisting of capsules suspended in the air above modular megastructures.

Tokyo Bay, unbuilt

A post shared by Azure Verdi (@azureverdi)

A photo posted by on

Kenzo Tange ambitiously proposed reorganising the fast-growing capital bye creating a linear city of connective 'modules' across Tokyo Bay, alongside multi-level looping highways.

Helix City, unbuilt

A post shared by charo vega (@_charovega)

A photo posted by on

Kisho Kurokawa reimagined Tokyo’s Ginza district in 1961 as an endlessly spiralling megastructure, growing both horizontally and vertically, inspired by DNA’s double helix – reflecting the Metabolist vision of cities as living organisms.

The Japanese metabolism movement's legacy

Metabolism’s prominence waned from the 1980s, as Japan shifted towards more mainstream urban expansion fuelled by the nation’s continued rapid-fire economic growth. However, the theoretical imprint of the Metabolist movement remained unfaded and far-reaching, continuing to influence urban planners and architects globally, even today, with its timeless utopian vision of shaping an adaptable, futuristic world which is endlessly renewed, just like nature.

Danielle Demetriou is a British writer and editor who moved from London to Japan in 2007. She writes about design, architecture and culture (for newspapers, magazines and books) and lives in an old machiya townhouse in Kyoto.

Instagram - @danielleinjapan