How an icon of Japanese Metabolist architecture took on a life of its own – even after its destruction

When Kishō Kurokawa designed the modular Nakagin Capsule Tower more than 50 years ago, he imagined it boarding ships and travelling the world. Now it has, thanks to a new show at MoMA

Design has long derived inspiration from nature, but one of the most eccentric and captivating examples took the form of a 13-storey skyscraper in Tokyo composed of 140 prefabricated, 100 sq ft pods jigsawed around a concrete-and-steel structure. The Nakagin Capsule Tower, completed by the Metabolist architect Kishō Kurokawa in 1972, was meant to grow, adapt and evolve – just like a living organism.

‘If you replace the capsules every 25 years, it could last 200 years,’ Kurokawa said in a 2007 interview. ‘It’s recyclable. I designed it as sustainable architecture.’ Until 2022, when it was demolished, the tower’s distinctive interlocking grey cubes with porthole windows were iconic elements of the local skyline, drawing architecture buffs and Instagrammers alike to admire its form.

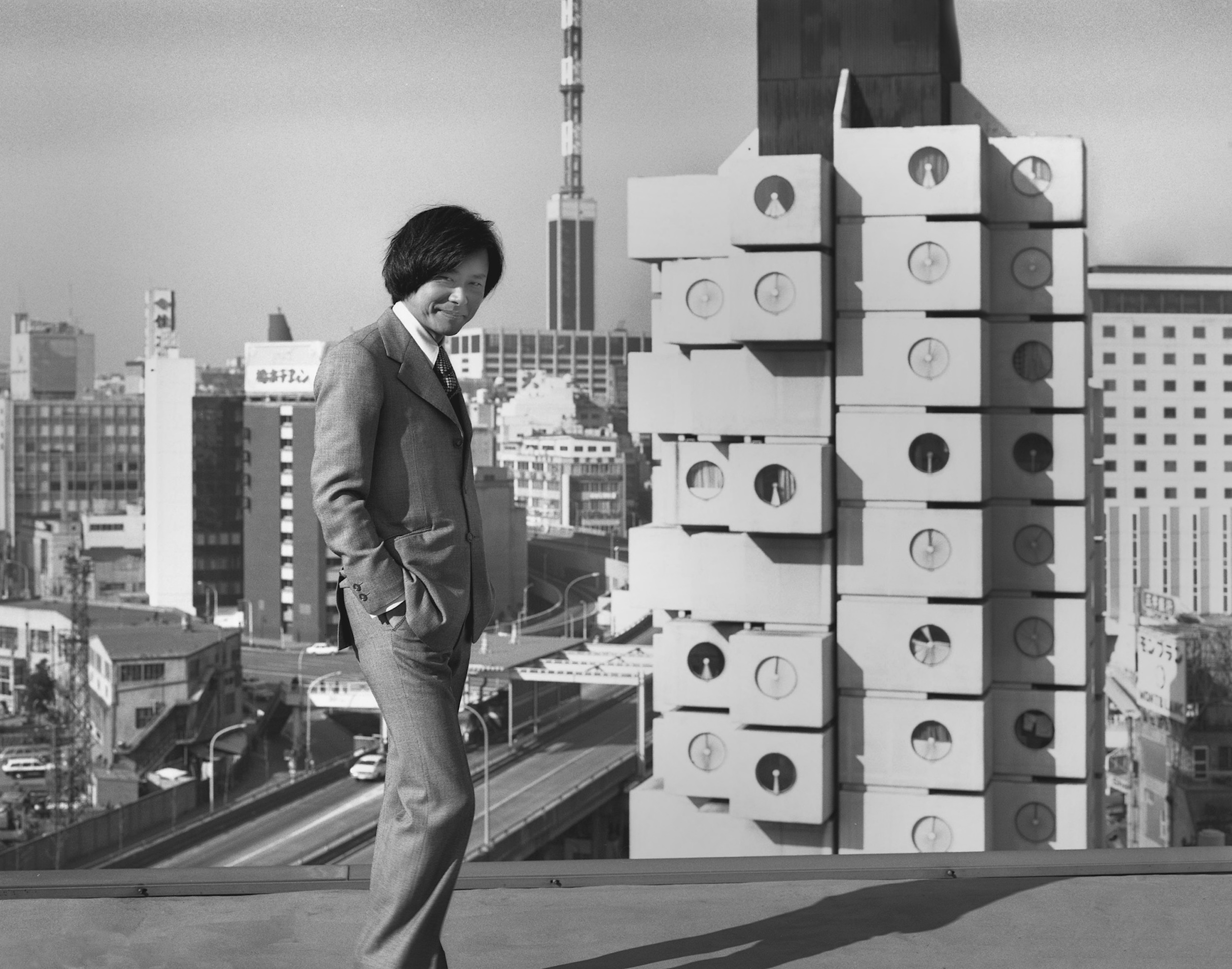

The tower, as it appeared in 1972

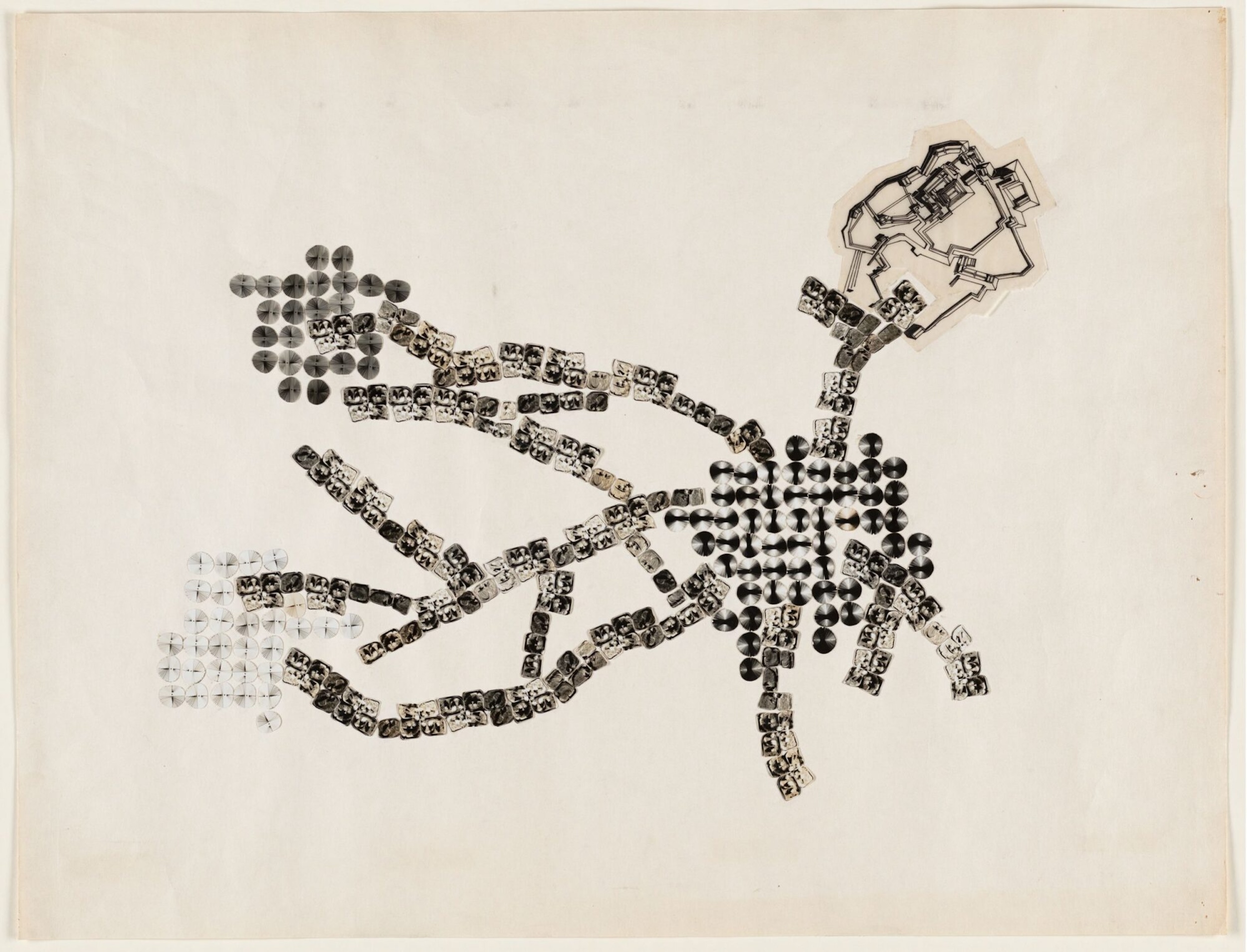

Now, the tower is the subject of an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Organised by assistant curator Evangelos Kotsioris and curatorial associate Paula Vilaplana de Miguel, ‘The Many Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower’ (until July 2026) celebrates the building’s inventive design and the impact it had on the people who lived in it. It is an exhibition about innovative ideas as well as post-occupancy. It includes a fully restored pod, an original display model, architectural drawings, archival marketing materials, films and photographs of residents showing how they inhabited their pods, as well as an interactive virtual tour of the building, showing the state of the structure in the twilight of its life.

‘We knew about the history of the project, but the more the two of us looked into the specifics, the reality of how things unfolded was a much more interesting story to tell than just the intentions of the architect,’ Kotsioris says.

Kishō Kurokawa in front of the completed Nakagin Capsule Tower in 1974

Kurokawa’s building represented a new form of urban living during a time of rapid cultural, technological and economic change in Japan. As Kotsioris writes in a book accompanying the show, Kurokawa ‘envisioned the tower as the habitat of Homo movens, the modern individual in an increasingly mobile society’.

While the project was built over 50 years ago, the ideas still feel resonant for today. Cities around the world are contending with a worsening housing shortage and are struggling to build units that meet their changing demographics, including a rising rate of single people. Kurokawa’s idea anticipated the micro apartment, a type of building that today’s architects are exploring to solve the crisis.

The Nakagin Capsule Tower was originally billed as a pied-à-terre for businessmen who commuted to Tokyo for work and whose families lived elsewhere. The tiny pods, measuring just 8ft x 13ft, featured a bed; a wall unit with a built-in desk, television, closet and sink; and a bathroom. ‘In a way, it's also a showcase of Japanese technology: a Sony TV, Pioneer headphones, a Sharp calculator, a Sanyo refrigerator,’ Kostriosis says. ‘So it was this kind of combination between a device and a product and an architectural enclosure.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The experience is ship-like efficiency. Nobuo Abe, an architect in Kurokawa’s firm who led the design and construction of the capsules, was also a sailor and came up with the idea to have all the furniture on the periphery.

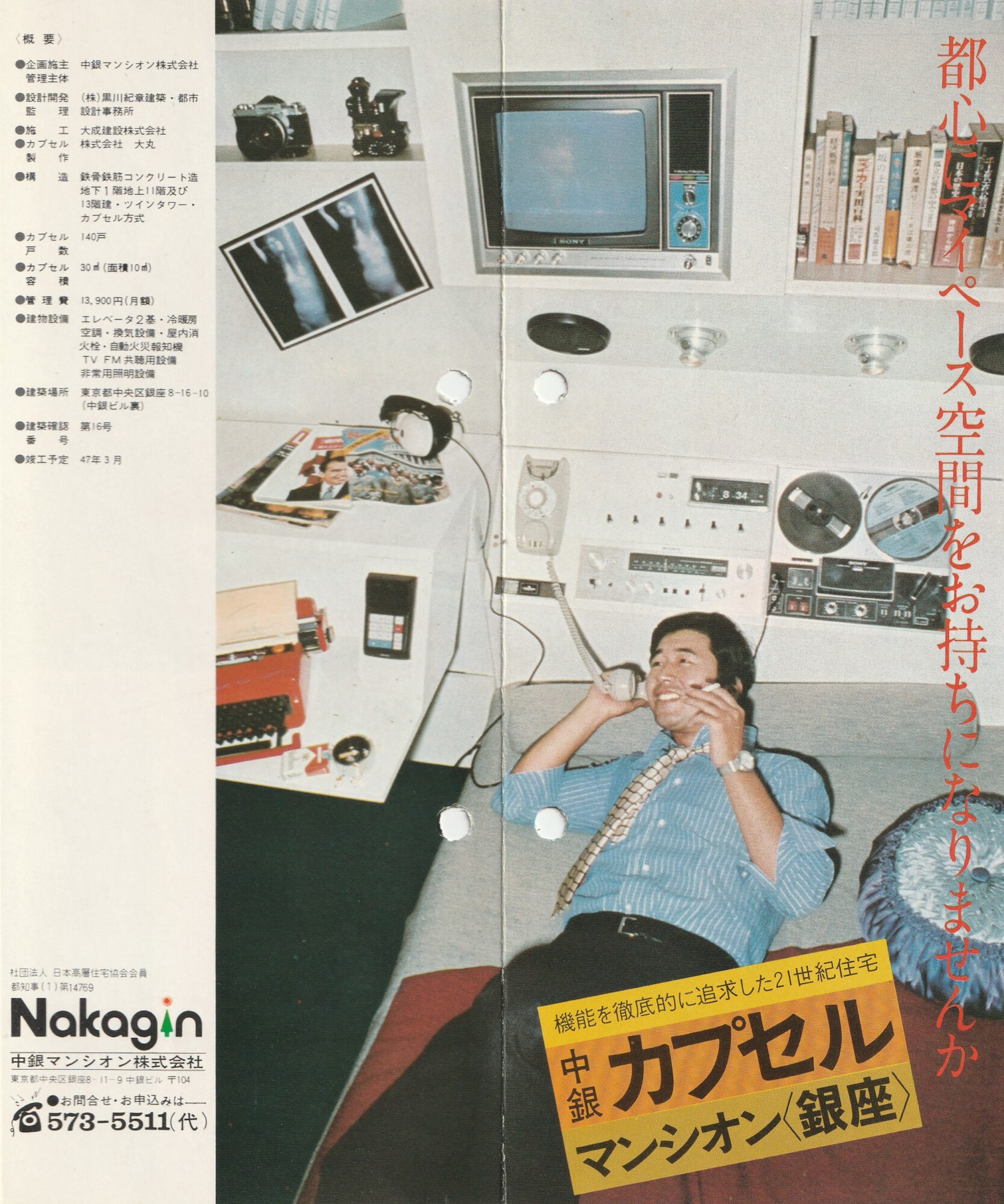

The tower was advertised as a crash pad for Japanese businessmen

Because the building was the first of its kind, Kurokawa also took great care in how it was positioned in the real estate market. The Nakagin company, with support from the firm, created pamphlets and instruction manuals that borrowed from automotive sales and even offered ‘deluxe’ versions of the pods that featured optional amenities, like a stereo system.

‘The capsule being a single-occupancy space was really meant to reinforce your personal perspective, which in the Japanese societal context was seen as an aberration,’ Kotsioris says. ‘They use language and graphics to construct a lifestyle; it’s not just about a building in the conventional sense.’ The curators digitised this ephemera so that visitors to the exhibition can flip through.

The tower is ‘a product of its time’, Vilaplana de Miguel adds. ‘When consumerism, TV and commercials started to circulate more widely, architects like Kurokawa decided to be part of it. He was a great businessman himself and he really embraced the commercial aspect.’

A night view of the tower, with resident Takayuki Sekine shown peeking through a window in 2016

When the building’s units hit the market in 1972, they sold out in two days. Initially, businessmen moved in. Then in the 1980s, when Japan’s economy crashed, the prices plummeted and younger residents, students and artists moved in. Later, when the building’s demolition seemed imminent, it attracted people who were fans of the building and Kurokawa’s work. ‘All kinds of quirky people start to move in and become obsessed with actually preserving its memory or legacy or afterlife,’ Kotsioris says. ‘And it’s thanks to them that we, and other institutions, have fragments of its history.’ (The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and The Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama also acquired pods.)

Inside the capsule of Wakana Nitta (aka Cosplay Koe-chan) in 2020

Some recent residents included an anime cosplay DJ, who used her pod as a streaming booth for her shows; Kurokawa's own son, Mikio, who transformed one into a library; and an interior designer who renovated his space to have an industrial, Steampunk aesthetic. And, naturally, the last cohort who lived there included preservationists who restored units to Kurokawa’s original vision, down to the light switches. These various shifts reflect the core idea of the building: it can be refashioned again and again.

‘Metabolists have this idea of buildings evolving over time and reshaping as society changes,’ Vilaplana de Miguel explains. ‘Kurokawa based his project on Buddhist and Zen philosophies of cycles of life.’

A pod interior, as seen at MoMA

Sadly, the building deteriorated. Kurokawa envisioned replacing the pods every 25 years, which did not occur. Their flat roofs collected water, making the units vulnerable to leaks and moisture damage. The bright pink and orange stairwells in the tower (which informed the hues of the exhibition’s gallery walls) were eventually painted over in grey. And there were asbestos concerns. It would have been cost-prohibitive to try to fully restore the building due to the deferred maintenance. But the residents who rallied for its preservation managed to save 23 capsules and fully restore 14 of them.

Normally, when a building is demolished, especially one with as rich a history as the Nakagin Capsule Tower, it is perceived as a tragic loss. But Kotsioris notes that the dismantling of the pods, their distribution to museums around the world, and reincarnation as the subject of exhibitions, aligns with the lifecycle concept that Kurokawa imagined for his tower – even if he didn’t predict its eventual outcome. In a 1972 promotional film for the tower that screens in the gallery, we see a pod loaded onto a ship with the narrator explaining a vision the architect had in which the pod’s resident could remove their unit from the building and have it travel with them.

Installation view of ‘The Many Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower'

Twelve of the tower’s former residents journeyed to MoMA to celebrate the exhibition’s opening last week. In remarks, Tatsuyuki Maeda, a former resident who led preservation efforts, said that he was ‘very grateful to everyone involved for allowing us to exhibit our beloved capsule’.

That Kurokawa was able to create a building that so many people cherished and felt deep personal connections to is perhaps his most enduring achievement, and one that will live on indefinitely.

‘The Many Lives of the Nakagin Capsule Tower’ is on view at MoMA through 12 July 2026.

Diana Budds is an independent design journalist based in New York

-

Pierre Yovanovitch on reviving French design house Ecart, and the ‘beautiful things’ ahead

Pierre Yovanovitch on reviving French design house Ecart, and the ‘beautiful things’ aheadTwo years after acquiring Ecart, Yovanovitch unveils his plans for the design house founded by Andrée Putman and now relaunched with a series of reissues by American-Hungarian émigré Paul László

-

Rome’s hottest new bar is a temporary art installation – don’t miss it

Rome’s hottest new bar is a temporary art installation – don’t miss itVilla Lontana presents ‘Bar Far’, a striking exhibition by British artists Clementine Keith-Roach and Christopher Page, where nothing is what it seems

-

Apple unveils Creator Studio, a new subscription service for its top-tier creative apps

Apple unveils Creator Studio, a new subscription service for its top-tier creative appsApple Creator Studio brings together Logic Pro, Final Cut Pro and a host of other pro-grade creative apps, as well as a new level of AI-assisted content search

-

The New Museum finally has an opening date for its OMA-designed expansion

The New Museum finally has an opening date for its OMA-designed expansionThe pioneering art museum is set to open 21 March 2026. Here's what to expect

-

This Fukasawa house is a contemporary take on the traditional wooden architecture of Japan

This Fukasawa house is a contemporary take on the traditional wooden architecture of JapanDesigned by MIDW, a house nestled in the south-west Tokyo district features contrasting spaces united by the calming rhythm of structural timber beams

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthFrom wineries-turned-music studios to fire-resistant holiday homes, these are the properties that have most impressed the Wallpaper* editors this month

-

Clad in terracotta, these new Williamsburg homes blend loft living and an organic feel

Clad in terracotta, these new Williamsburg homes blend loft living and an organic feelThe Williamsburg homes inside 103 Grand Street, designed by Brooklyn-based architects Of Possible, bring together elegant interiors and dramatic outdoor space in a slick, stacked volume

-

New York's iconic Breuer Building is now Sotheby's global headquarters. Here's a first look

New York's iconic Breuer Building is now Sotheby's global headquarters. Here's a first lookHerzog & de Meuron implemented a ‘light touch’ in bringing this Manhattan landmark back to life

-

This refined Manhattan prewar strikes the perfect balance of classic and contemporary

This refined Manhattan prewar strikes the perfect balance of classic and contemporaryFor her most recent project, New York architect Victoria Blau took on the ultimate client: her family

-

‘It’s really the workplace of the future’: inside JPMorganChase’s new Foster + Partners-designed HQ

‘It’s really the workplace of the future’: inside JPMorganChase’s new Foster + Partners-designed HQThe bronze-clad skyscraper at 270 Park Avenue is filled with imaginative engineering and amenities alike. Here’s a look inside

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthThis September, Wallpaper highlighted a striking mix of architecture – from iconic modernist homes newly up for sale to the dramatic transformation of a crumbling Scottish cottage. These are the projects that caught our eye