Project Japan: Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Not content with being the subject of an expansive retrospective at the Barbican, debating post-modernism at the V&A, opening the new Maggie's Centre Glasgow and putting the finishing touches to the New Court Rothschild Bank HQ in the City, Rem Koolhaas has also taken time out from his global schedule to launch his new book, 'Project Japan, Metabolism Talks...' A collaboration with his long-term co-conspirator Hans Ulrich Obrist, the book is an oral and visual history of one of the most influential, yet elusive, movements in modern architecture, the Japanese Metabolist Movement.

Koolhaas and Obrist came to the subject via their shared enthusiasm for the long-form interview, delving deep into the country's past to uncover the origins and legacy of this spirited movement, with its combination of emerging technology and traditional architectural strategies. The results were often other-worldly, megastructural in their ambition and yet still human in scale despite their utter obsession with the role of technology in society. Metabolism effectively culminated in Japan's magnificent Expo '70 at Osaka, a sprawling proto-high tech wonderland that cemented the nation's global image as a technological utopia. Wallpaper* sat down with Koolhaas and Obrist to take about the genesis of the book and what Metabolist architecture means today.

This feels like a very personal, intense project. At what point did you think there was more archaeology to be done on the Metabolists than what was already available?

Hans Ulrich Obrist: I knew about Metabolism through Rem, from the first day we met, when we did the 'Cities on the Move' exhibition - it was a very hectic day and he needed to catch a plane to Hong Kong, so he said it would be better not to discuss Asia in Rotterdam, but in Hong Kong. So we all got a plane and starting researching Asian cities. While in Asia we found these post-Metabolists in Singapore but also the core Metabolists in Japan, like Kurokawa and Maki, and Rem suggested I should interview them. So it all started 16 years ago in 1995.

Rem Koolhaas: My interest in Metabolism was always strong, firstly as a student in '68, but it was reactivated when I went to Singapore. There were projects that had been inspired by Metabolism and they were a more successful realisation than they had been able to do in Japan.

Presumably this was a very different project for Rem as an architect than for you as a historian. Did you reveal a different truth of how we look at Metabolism?

HUO: Rem and I have always had a practice of doing interviews, it's something we have in common. The first interview we did together was Philip Johnson and we went on from there. I came up with the format of the marathon and at some stage we thought it would be interesting not only to do a portrait of a person but of a whole movement. We live in a time when there are less manifestos and movements. In art, which is my field, you had Fluxus, you had Dada, and now you have less artistic movements. There are manifestos, but they are more individual. In Rem's field it is the same.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

RK: We wanted to reconstruct how that worked. The whole point of writing about Singapore was the anticipation that architecture and artistic movements are no longer Western and are instead moving to the East. Metabolism is the first non-Western avant-garde. One thing that is very crucial to the book is that we not only interviewed architects but also their contacts. We discovered that to some extent this whole movement was willed by the [Japanese] state, so we had to reconstruct this invisible part of the movement.

HUO: It became obvious that Tange was a key influence; it was all triggered by him. So we interviewed his two widows to go deeper and as a result we had many, many trips to Japan. That's also why in the end we called it Project Japan

RK: The discovery was that this movement was an ambitious enterprise to change the face of Japan, simply because there was an awareness of Japan's inherent weaknesses - earthquakes, tsunamis, but also over-concentration in the cities.

Do you think this kind of intense research is important to architectural practice today?

RK: What is also obvious is that by going back 50 years we were able to reconstruct the difference between architecture as a public issue and architecture as a private issue. Today the initiative, as you know, has shifted from the public to the private sector, so it is also a reconstruction of what the public sector can do.

What would you say the legacy of the Metabolists is today?

RK: For instance if you look at this building [the Barbican], you can see that is a kind of Metabolist building with a very strong idea, and a noticeable dedication to ideas.

HUO: Many of the projects, like the Marine City, continue to be quoted by architects because of their optimism. [Arata] Isozaki always injected a certain portion of doubt because he felt that maybe Metabolism was too optimistic - it was a movement of extraordinary optimism. We discussed Metabolism on our many trips to China and we realised that Metabolism has an influence on the Chinese optimism of the last couple of years.

RK: ...or that it ought to have an influence...

HUO: Maybe the book can help there - it can be a toolbox.

RK: It took so long because we interviewed people a number of times. But also we needed to reconstruct key episodes in the history of Japan to really make sense of it.

HUO: If you look at Japan, there is something very interesting about Japanese architecture, it's a Japanese miracle. I mean generation after generation in Japan produces great people. There is this continuum. It goes from Tange through Metabolism, to Isozaki's non-involvement, to the next generation, which is Toyo Ito, the next generation, which is Seijima and Nishizawa, and then the children of Seijima, like Ishigami, etc., it just seems endless.

RK: That is also the family that I feel most at home with, in architecture.

HUO: The Metabolism research ended up being real research into Tange as well. We went to his office. We looked at all of his buildings. It was also research into where this Japanese miracle of architecture came from. In the West there is more rupture, whilst in Japan there is a continuum, where one generation helps the next generation and so on.

How would you characterise Expo '70 in terms of influence?

RK: A moment you could feel euphoric about the future of the world. Maybe the last one.

HUO: It's interesting to look at it now because it's an expo that produced so much reality and so many extraordinary things. It was a true concrete utopia. And if you look at what expos have produced since, it's maybe slightly less urgent. As a curator I always think how can we do an expo that is urgent for now.

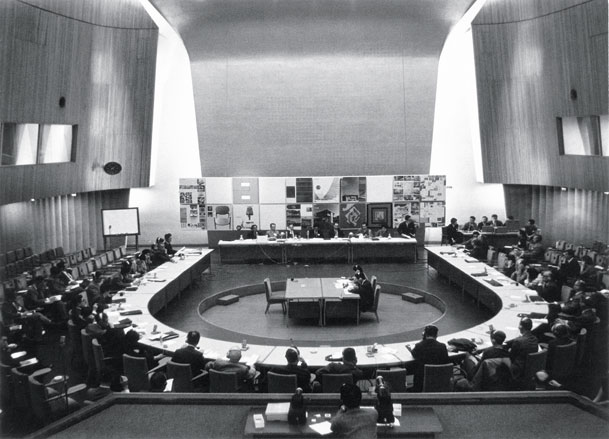

Inside the book: The World Design Conference, Tokyo, 1960

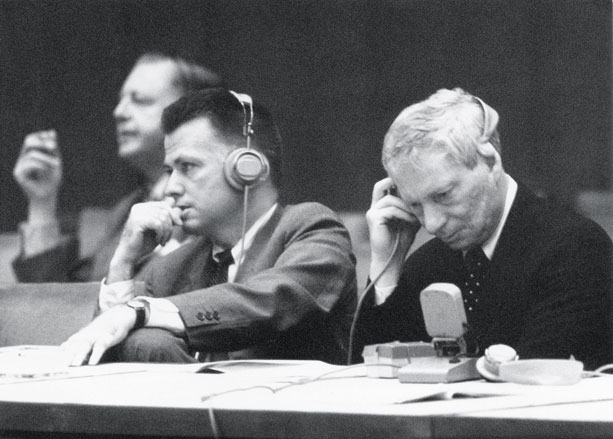

The World Design Conference, Tokyo, 1960. A panel with Paul Rudolf (left) and Louis Kahn (right)

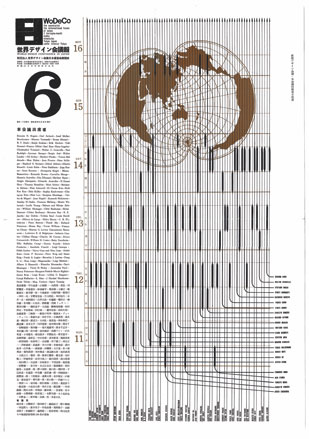

World Design Conference Bulletin No.6, 1960. Designed by Gan Hosoya

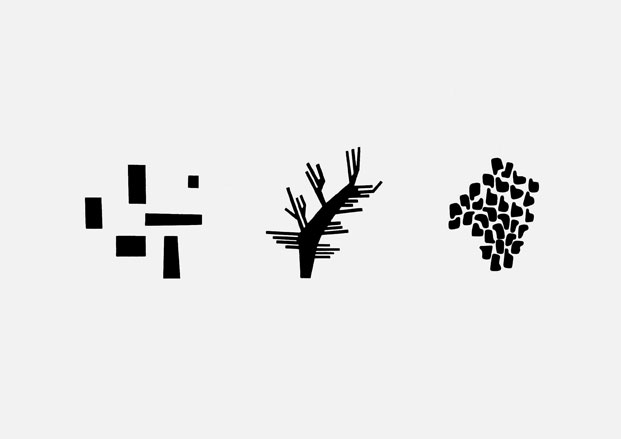

Three types of collective form by Fumihiko Maki, as identified and explored in Investigations in Collective Form, 1964

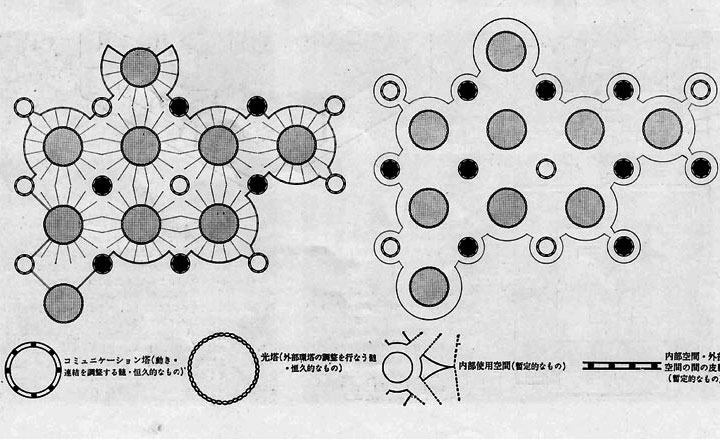

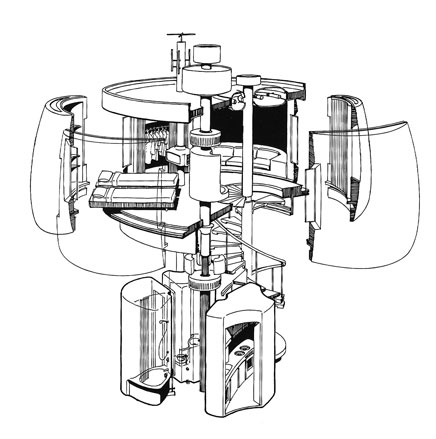

The Golgi Structure by Fumihiko Maki, 1968. Plans and diagrams

On an early day of TV, Masato Otaka presents Sakaide Artificial Ground, a social housing project on Shikoku island. Next to him, Kurokawa presents Helix City (a small model sits next to the ashtray on the table). 1963

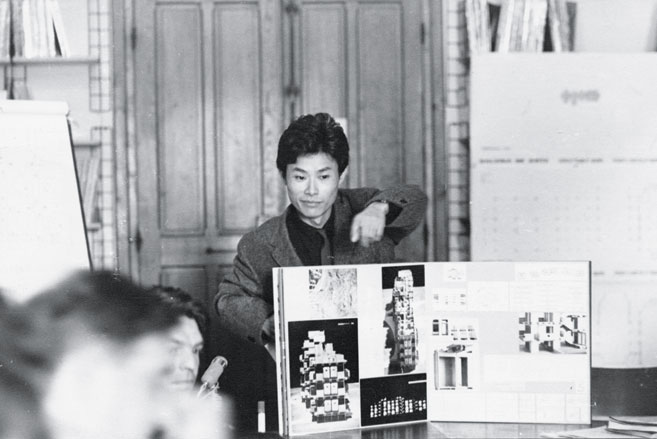

Kisho Kurokawa, 28, presents his Metabolist works at the Team 10 meeting at Abaye Royaumont, near Paris. 1962

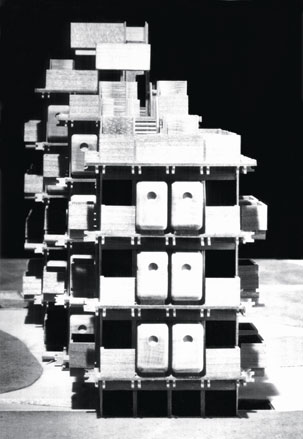

Box-type mass-produced apartments by Kisho Kurokawa, 1962

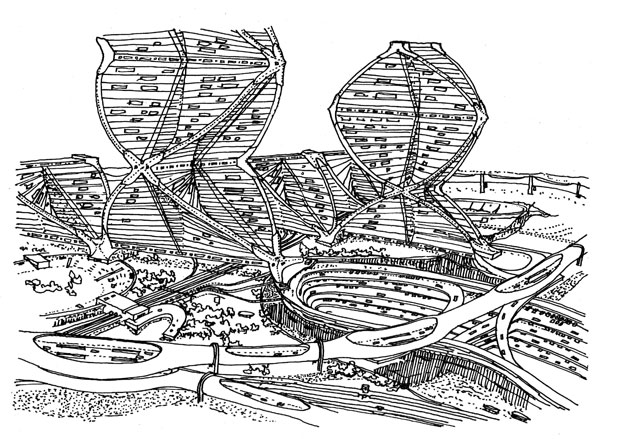

Helix City by Kisho Kurokawa, 1962

Wall City by Kisho Kurokawa, 1959

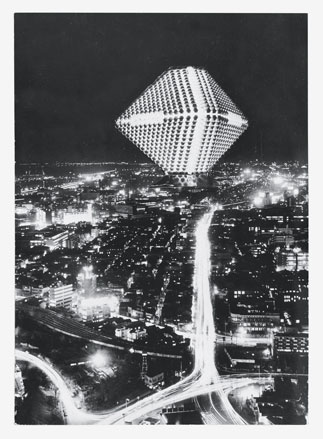

Dwelling City by Kenji Ekuan, 1964. Collage

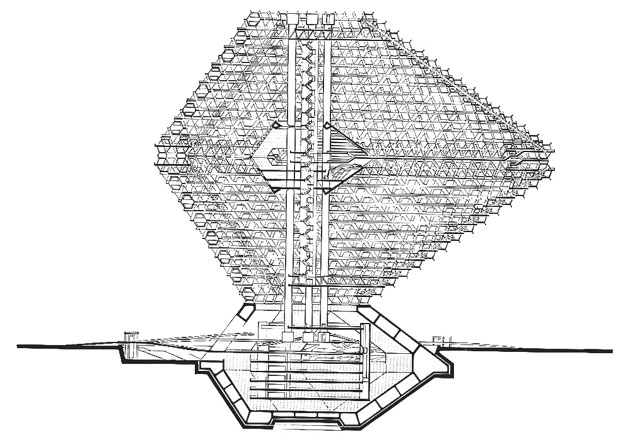

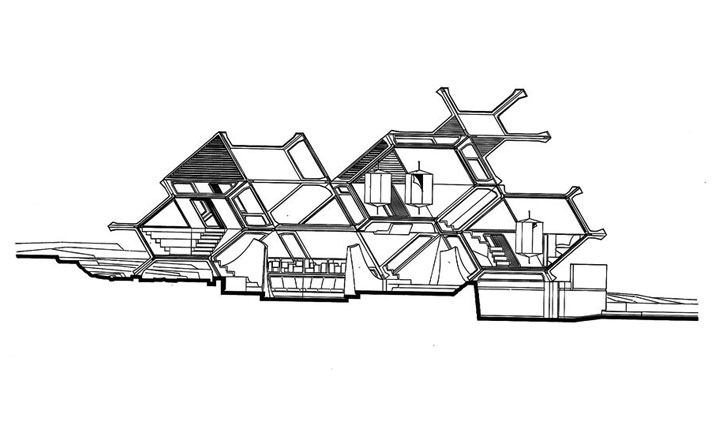

Dwelling City by Kenji Ekuan, 1964. Section

Pumpkin House by Kenji Ekuan, 1964. Perspective drawing

Tortoise House by Kenji Ekuan, 1964. Section

Tortoise House by Kenji Ekuan, 1964. Model

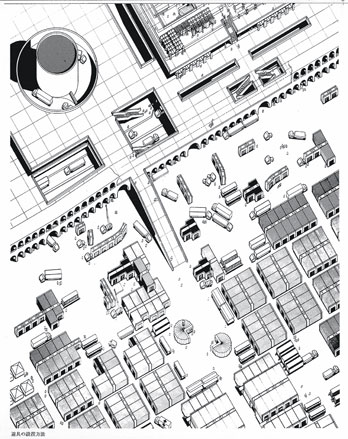

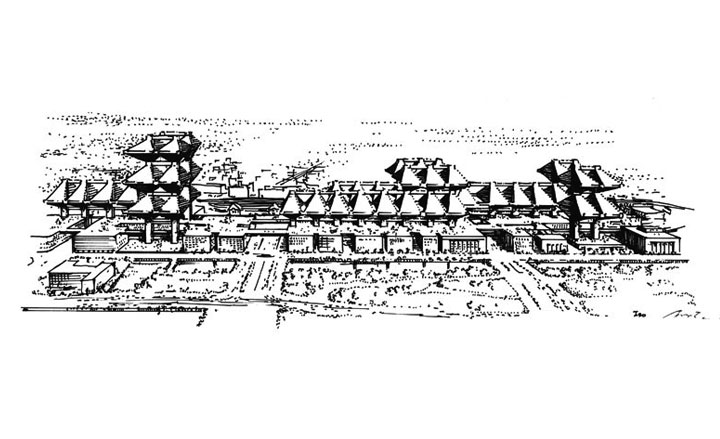

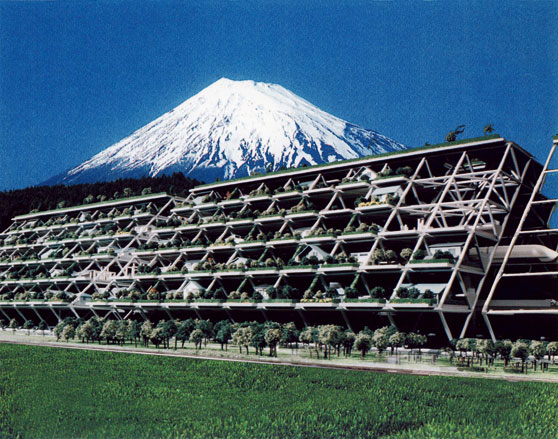

Masterplan for the Pilgrim Accommodation for Muna (Mina), Saudi Arabia, 1974

Incubation Process by Arata Isozaki, 1962

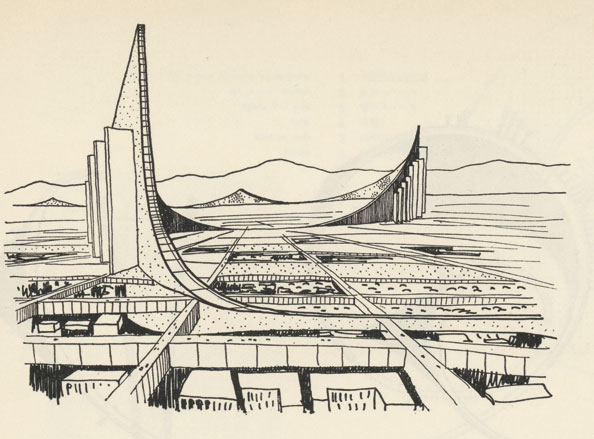

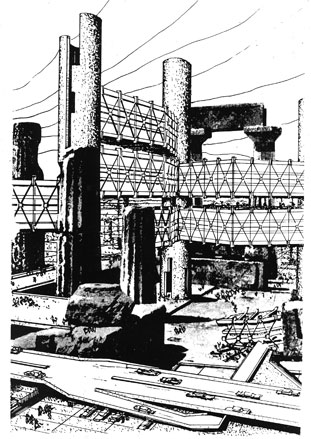

Cluster in the Air, Marunouchi Project, by Arata Isozaki, 1963

Under the big roof of the Festival Plaza, Osaka Expo '70, photographed by Arata Isozaki. 1970

Post-occupancy documentation: Nakagin Capsule Tower, Tokyo by Kisho Kurokawa, photographed in 2009 by Charlie Koolhaas

Post-occupancy documentation: Yamanashi Culture Center, Kofu by Kenzo Tange, photographed in 2009 by Charlie Koolhaas

Post-occupancy documentation: Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Building, Tokyo, by Kenzo Tange, photographed in 2009 by Charlie Koolhaas

Tower-shaped Community by Kiyonori Kikutake, 1958

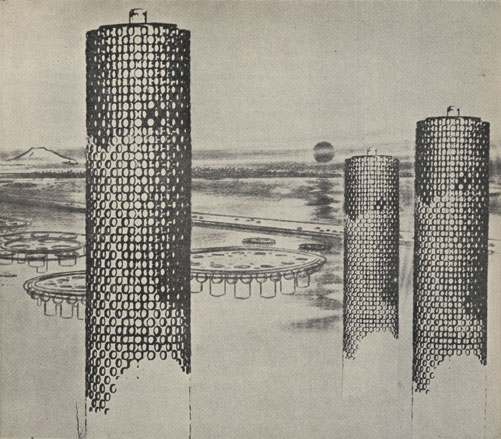

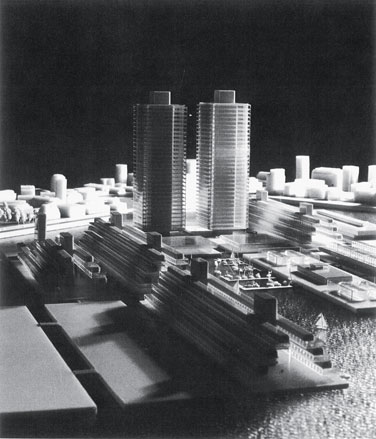

Marine City by Kiyonori Kikutake, 1958

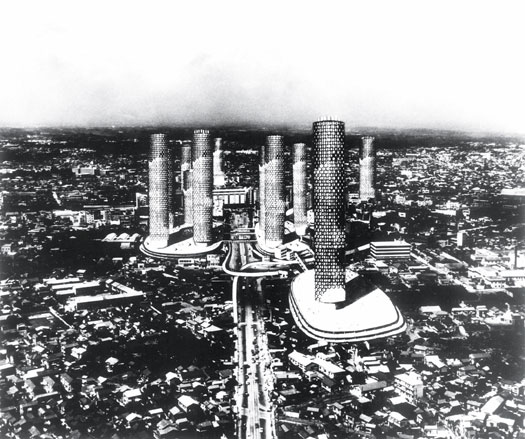

Ikebukuro Plan by Kiyonori Kikutake, 1962

Tree-shaped Community by Kiyonori Kikutake, 1968

Statiform Structure Module by Kiyonori Kikutake, 1972. Collage

KIC project by Kiyonori Kikutake, 1975. Collage

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.