Diane Arbus at David Zwirner is an intimate and poignant tribute to her portraiture

In 'Diane Arbus: Sanctum Sanctorum,' 45 works place Arbus' subjects in their private spaces. Hannah Silver visits the London exhibit.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

American photographer Diane Arbus was drawn to the other, celebrating the fringes of society in a prolific body of work created throughout the Fifties and Sixties. Her unflinching portraits, including of nudists, socialists, circus performers and transvestites, awarded her subject a respect which at the time was otherwise entirely absent.

A comprehensive exhibition earlier this year of over 400 works, at New York’s Park Avenue Armory, has returned Arbus firmly back into the public consciousness. Now, in London, the emphasis shifts to intimacy over scale, with the opening of 'Diane Arbus: Sanctum Sanctorum,' an exhibition of 45 photographs made in private places between 1961 and 1971. The exhibition will go on to travel to Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco in spring 2026.

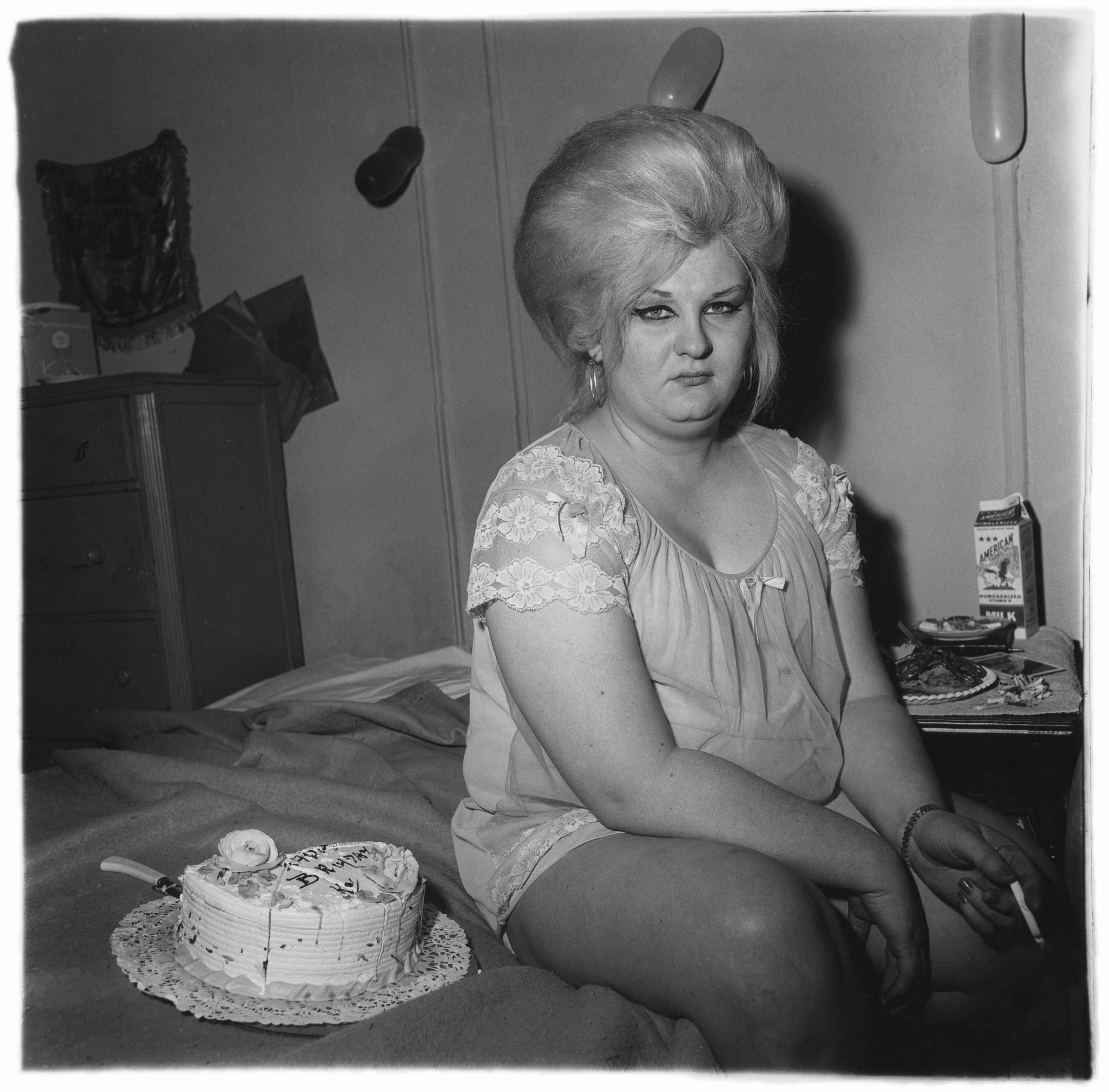

Diane Arbus, Female impersonator on bed, N.Y.C. 1961

Before the opening, I walk round the gallery with Jeffrey Fraenkel, who has worked closely with the Estate of Diane Arbus over the years. ‘I first saw Arbus’s work in a magazine, and there was just electricity in the image,’ he says. ‘I had never seen anything like it. It assured me there was a much bigger world out there than the world that I was growing up in. And that was reassuring.’

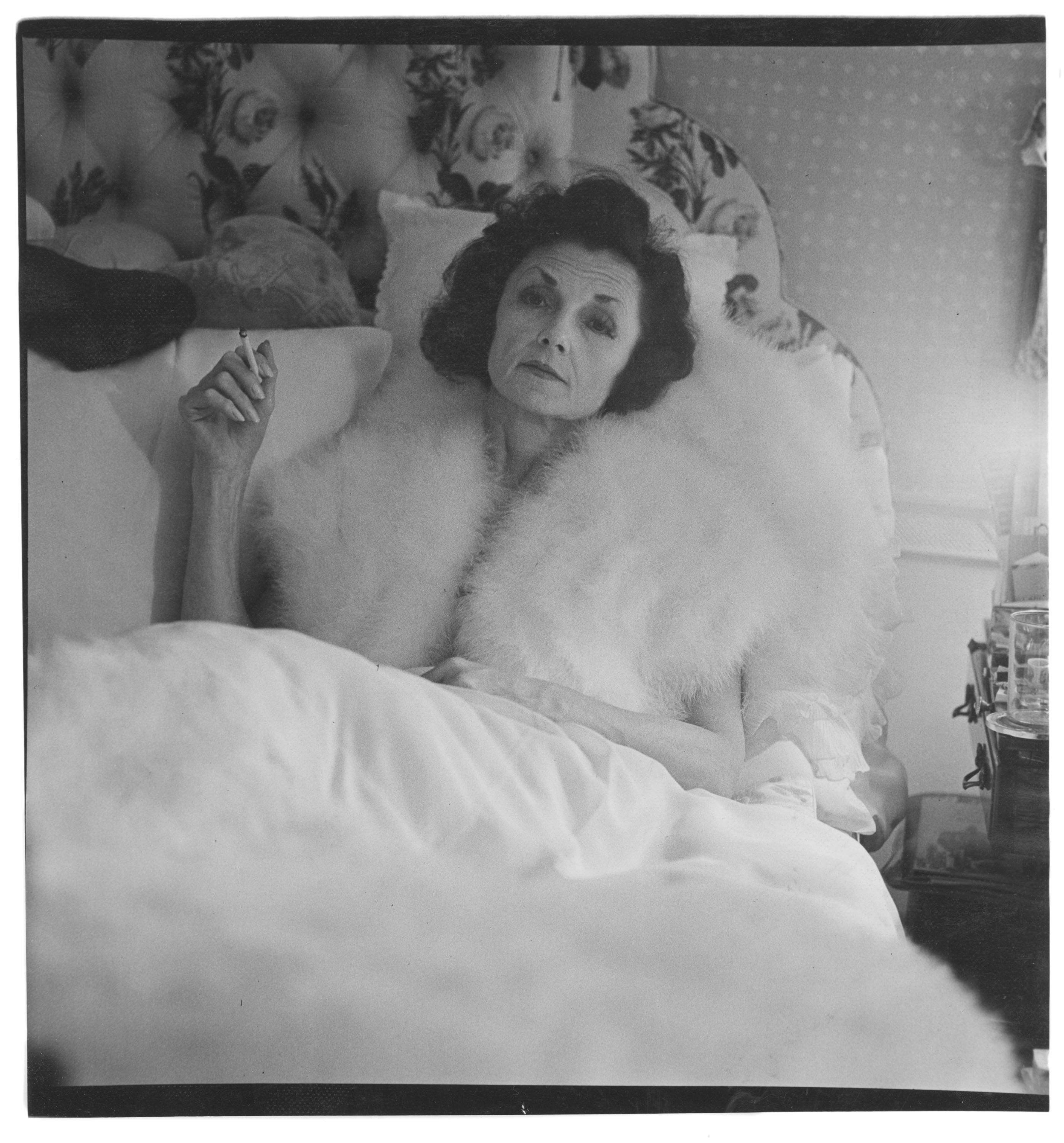

Diane Arbus, Brenda Diana Duff Frazier, 1938 Debutante of the Year, at home, Boston, Mass. 1966

Over the years, Fraenkel noticed how many of Arbus’ works were taken in the intimate spaces of her subjects – most notably, their bedrooms. These works speak to the level of trust Arbus inspired, as a photographer; a rare move, when considering photography was still disdained as an art form. In some images here, the subject confronts the photographer. In others, caught naked, mid-embrace, they act like she - and by extension, us - is not there at all. What was Arbus, the third person in the room, doing there? ‘There’s more than just respect there, there is trust,’ adds Fraenkel.

Arbus’ work is unique for being free from judgement. She avoided cropping images, displaying the full negative – complete with uneven black borders – as a way of taking the attention away from the photograph, and onto the human being it contained. Here, with the focus on the home, it is a method laced with a particular poignancy. ‘You think you're seeing it all, and then there's more. You look and realise – that's the refrigerator. Those are all the dishes in the sink. It means it’s their entire home. We're seeing everything in one room.’

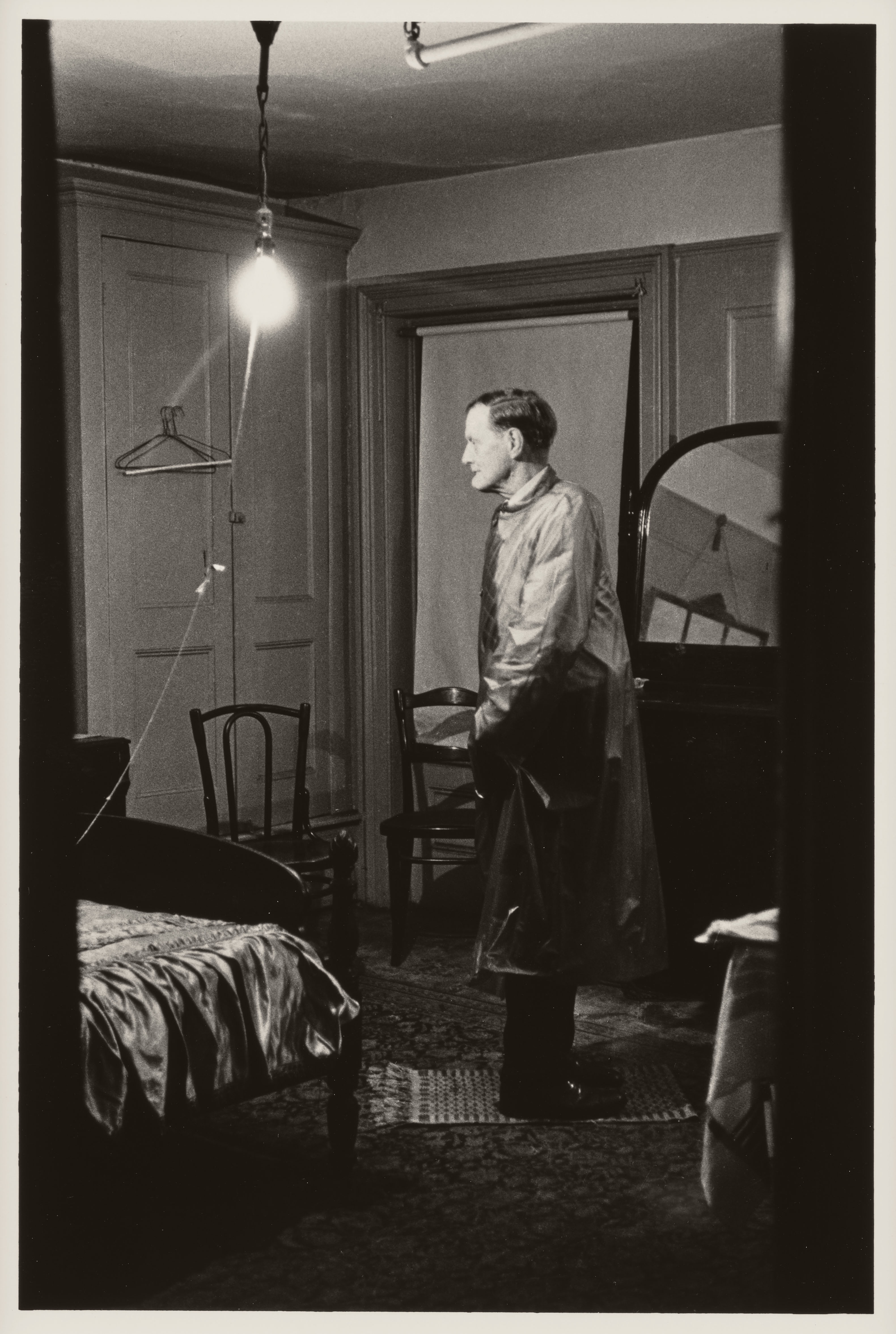

Diane Arbus, The Backwards Man in his hotel room, N.Y.C. 1961

While we are invited into these intimate spaces, to offer up our own interpretation, Arbus reminds us, again and again, we are looking at a photograph. ‘Her use of flash is really genius,’ Fraenkel says. ‘It pulls all these details out.’ In the pupils of her subjects, there is a reflected pinprick of light, a gentle admonishment that we are looking at a representation of the person only, rather than at the person themselves. Arbus wants us to be aware we don’t know as much as we think we do.

The photographs here are united in their honesty. There is a vulnerability in little-seen works, such as Interior decorator at the nudist camp in his trailer, Mexican dwarf in his hotel room and A naked man being a woman. Elsewhere – in A blind couple in their bedroom, Husband and wife with shoes on in their cabin at a nudist camp and Two friends at home – there is a testament to love, and to the desire to be seen, and known.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

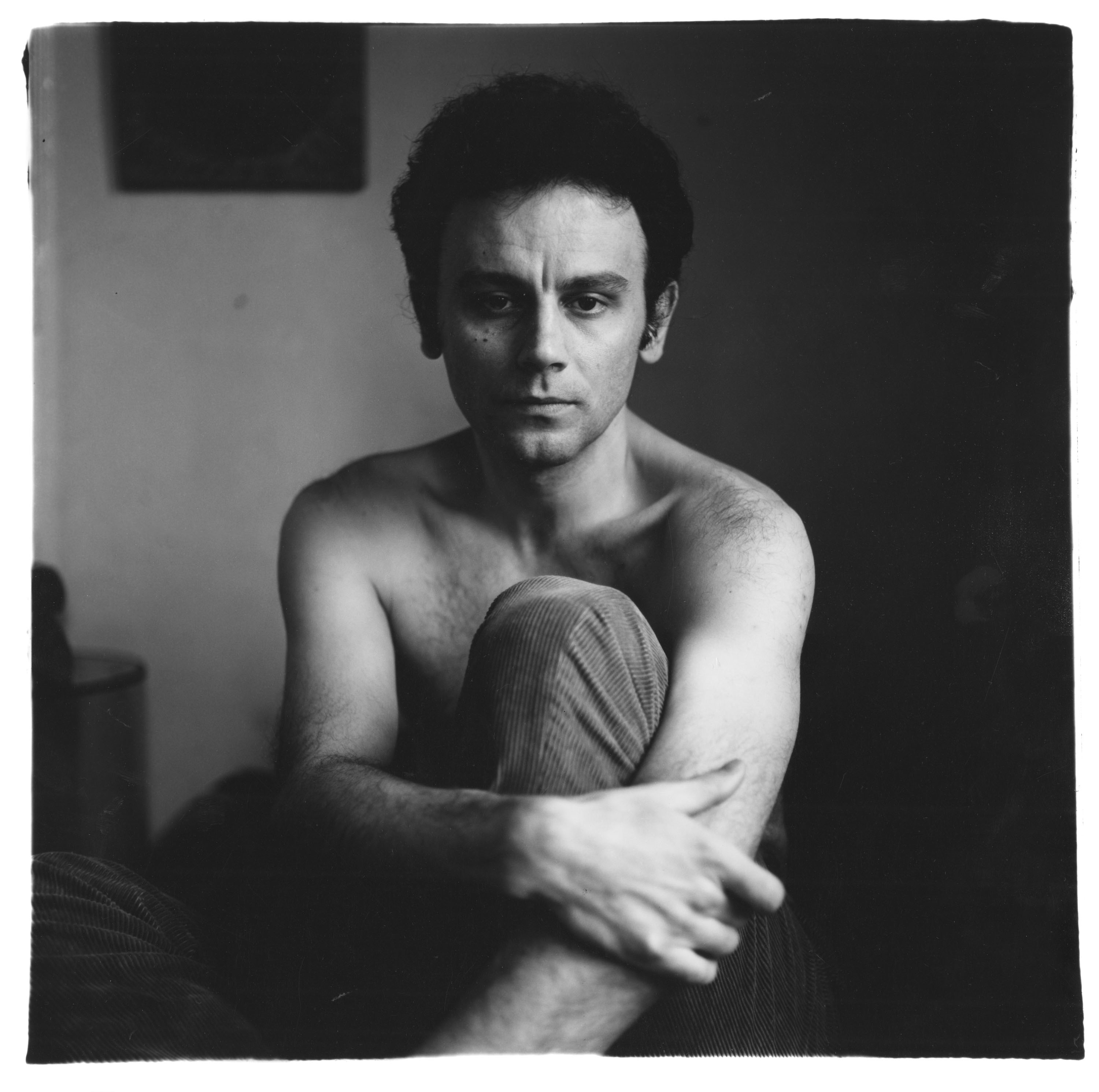

Diane Arbus, Lucas Samaras, N.Y.C. 1966

Be true to yourself, Arbus is saying, and that will be its own reward. ‘You can understand why these pictures made, and continue to make, so many people uncomfortable,’ says Fraenkel. ‘They don't have easy answers. There are people who would look and say that person is sick, and that would be their initial response. But Arbus had this angle in the world no one else did. I think she is in awe – of their courage, and their self-belief.’

Diane Arbus 'Sanctum Sanctorum' at David Zwirner London from 6 November–20 December, 2025. The exhibition will travel to Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco in spring 2026

Hannah Silver is a writer and editor with over 20 years of experience in journalism, spanning national newspapers and independent magazines. Currently Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*, she has overseen offbeat art trends and conducted in-depth profiles for print and digital, as well as writing and commissioning extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury since joining in 2019.