Treasure island: two new buildings alight on an art paradise in the Seto Inland Sea

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

For the past 20-odd years, a Japanese businessman has been working on an extraordinary series of buildings set across three small islands in the Seto Inland Sea. Naoshima, Teshima and Inujima comprise The Benesse Art Site Naoshima, a project spearheaded by Soichiro Fukutake, the executive adviser to Benesse Holdings Inc (the education, language and global leadership training group) and chairman of the Fukutake Foundation.

For the site’s development, Fukutake is working with a team of celebrated architects and artists to help him realise his dreams of creating another, truer Japan that is more in touch with its own tradition. The Benesse site’s collection of buildings now includes designs by some of Japan’s foremost architects – Tadao Ando, Ryue Nishizawa and Hiroshi Sambuichi have all worked there – and a staggering line-up of local and international artists such as Walter De Maria, James Turrell, Shinro Ohtake, Yukinori Yanagi, Lee Ufan and Rei Naito.

During the region’s popular Setouchi Triennale, activities spill over onto neighbouring islands, but it is on Naoshima, where it all started, that Fukutake’s plans gather pace. Hiroshima-based architect Hiroshi Sambuichi has just completed two landmark commissions there; the subtly grand Naoshima Hall and the small but exquisitely executed Matabe House. Only slightly larger than 8 sq km and with a population of around 3,000, the island of Naoshima lies between Honshu in the north and Shikoku in the south. To visit requires commitment, planning and time, as a trip from Tokyo (by plane, bus and ferry) takes more than half a day. But it is hard to visit the island without falling in love. From the old but well-kept wooden houses of Honmura and the friendly locals, to the beautiful sea and the nori fishermen working around the docks in Miyanoura, Naoshima has a lot to offer; and this is before you even get started with its exceptional museums.

Tadao Ando’s Chichu Art Museum is perhaps the best known. Fukutake isn’t shy about praising it and he doesn’t need to be. ‘I think I ought to receive a Nobel Prize for changing the definition of what a museum is. That is, if a Nobel Prize for culture existed,’ he laughs, seated on the tatami floor of the Matabe House. ‘To me, most of the major museums around the world are not really museums but merely exhibition halls for art. With the Chichu Art Museum, I believe I was able to show the world a new direction for art museums.’

Ando’s thoughtful architecture unfolds mostly underground, so as not to upset the landscape, and frames site-specific art by James Turrell and Walter De Maria, as well as five Monet Water Lilies that took Fukutake more than 20 years to acquire. A visit feels almost spiritual, and as most of the museum features natural light only, the experience changes during the day and according to seasons.

Fukutake also played a key role in the creation of the island’s latest two additions. When he was consulted by the mayor of Naoshima, who was looking for an architect for a new multipurpose hall and community centre on the island, he recommended Sambuichi. Fukutake had commissioned the architect to design the Inujima Seirensho Art Museum, which opened in 2008. Sambuichi cleverly adapted the ruins of an abandoned copper refinery using a distinctly eco-friendly approach. At the same time, Fukutake had a small plot of land on Naoshima and asked Sambuichi to work on an environmentally sensitive small house; his aim was for Matabe House to act as a benchmark for others’ homes on the island.

For Sambuichi, both the house and the hall are physical expressions of research he has been working on for the last four years – The Naoshima Plan. He has been studying how the wind, sun and water move on the island, comparing his findings to how buildings were actually planned. ‘The goal is to come up with a detailed plan to turn the whole island into a more sustainable and locally sound environment,’ he explains. At the moment, for example, he is looking at re-establishing a large area of terraced rice fields near Honmura. His research tells him it used to play a big part in naturally controlling the temperature of the village, as warm winds blew over the water of the irrigated fields, cooling before reaching the houses.

Wind was also a key consideration in the design of Naoshima Hall. The multipurpose hall, measuring roughly 1,000 sq m, uses a clever variation of a traditional irimoya hip-and-gable roof to control airflow within the building. At the top of the solid hinoki cypress beam roof, an air tunnel is positioned to receive the area’s frequent north-south wind. A sealable opening is placed at its heart and through the impressive shikkui (lime) plastered ceiling. When open, the force of the wind passing through draws up cool air from below. This ingenious cooling and ventilation system is about as eco-friendly as you can get, using just natural wind power.

The hall’s layout is kept simple. A large, central open-plan area can be used for sports and doubles as seating space, either with chairs or traditional Japanese tatami mats, when a play or concert is being performed on the beautifully crafted noh stage at the southern end of the building. There are also storage and dressing rooms at the sides and the back, while outside, a small raised stage extends into a shallow pond and out into a Japanese moss garden.

The roof of the complex’s other, much smaller structure (the 300 sq m community centre) hides four separate buildings; two tatami rooms, a small kitchen and a toilet structure positioned around a communal well. Its water can be pumped up on the roof to help cool the building. Everything in both the multipurpose hall and the community centre is made using the best available hinoki cypress, handmade washi paper, traditional shikkui plastering, earthen walls and stamped floor. The quality of the carpentry would befit a shinto shrine or a luxury ryokan in Kyoto.

Sambuichi’s experience in using natural resources and environmentally friendly designs was crucial in winning him the commission for Fukutake’s fairly modest Matabe House, which measures just a little over 200 sq m. The architect’s solution here involved renovating an old, traditional Japanese house and a small adjacent warehouse, adding an extension to the latter. ‘The renovated building can be used for entertaining guests and for meetings, while the various modern amenities, such as bathroom and kitchen, have been delegated to the new extension,’ he explains. The former retains a very traditional Japanese style, with all tatami mat flooring, floor-to-ceiling sliding doors and screens. The surrounding moss garden is partly brought indoors to purposely blur the line between inside and outside. It’s a simple space with no heating or insulation, set for use during the hot and humid summer months, when a gentle breeze runs through its open walls.

By contrast, the new extension appears distinctly modern. As in the design of Naoshima Hall, the roof immediately stands out. Like the community centre, it uses well water to control temperatures in the summer. The ground level is raised by 1.3m – this helps with cooling (which happens naturally by the wind blowing underneath), acts as a flood prevention measure and ensures the interiors get better natural light (a nearby hill casts a shadow over part of the site). Sambuichi spent more than two years ‘reading’ the area to fully grasp its challenges and potential. His thorough understanding of the locale, its history, traditions and climatic environment means that no design detail was left purely to taste or artistic whim.

All of Sambuichi’s buildings on Naoshima are true expressions of their environment and blend into their context with ease. While Matabe House is not open to the public, the hall and community centre both are, and with the third Setouchi Triennale about to kick off, now is the perfect time to visit Naoshima. The pilgrimage will be well worth it.

As originally featured in the April 2016 issue of Wallpaper* (W*205)

Hiroshi Sambuichi’s Naoshima Hall (pictured) is a large multipurpose space that can be used for sports or concerts, constructed from carefully sourced hinoki cypress, washi paper and shikkui plastering

Outside naoshima hall, a raised stage extends into a shallow pond and moss garden

A visit feels almost spiritual, thanks to the abundant natural light, that changes the experience seasonally and throughout the day

Inside, the hall can be furnished with either chairs or traditional Japanese tatami mats

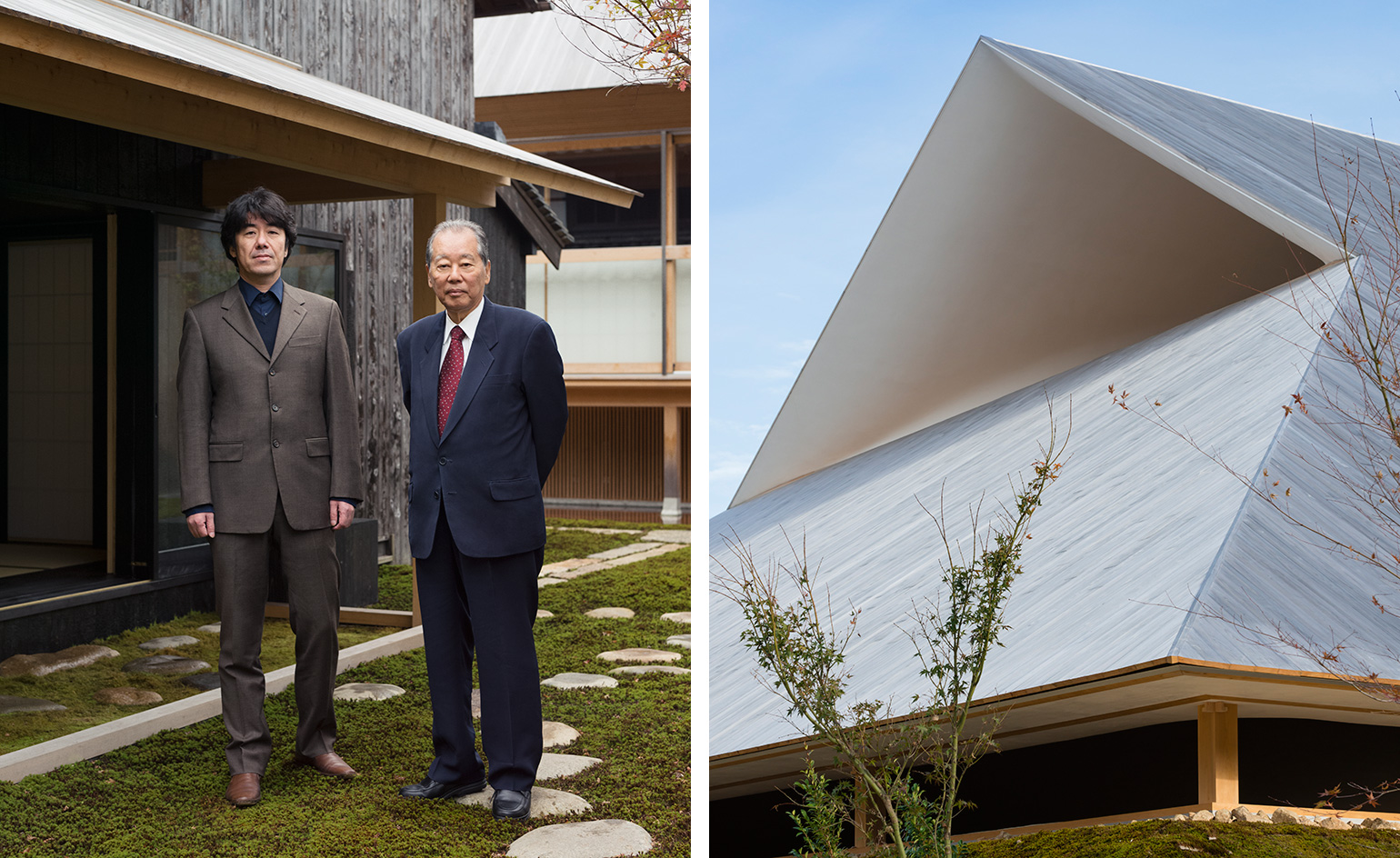

Pictured left: Hiroshi Sambuichi and Soichiro Fukutake. Right: an air tunnel is positioned on top of the hall’s roof – a variation of a traditional hip-and-gable roof – to control airflow within the building and receive the area’s north-south wind

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Benesse Museum website

Photography: Shigeo Ogawa

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Originally from Denmark, Jens H. Jensen has been calling Japan his home for almost two decades. Since 2014 he has worked with Wallpaper* as the Japan Editor. His main interests are architecture, crafts and design. Besides writing and editing, he consults numerous business in Japan and beyond and designs and build retail, residential and moving (read: vans) interiors.