Michael Graves’ house in Princeton is the postmodernist gem you didn’t know you could visit

The Michael Graves house – the American postmodernist architect’s own New Jersey home – is possible to visit, but little known; we take a tour and explore its legacy

You can visit many homes of modernist architects; this is not nearly so easy for the postmodernists. There are the Charles Moore houses in Austin and Santa Monica, and Charles Jencks' Cosmic House in London and... that's about it. Except for one that's nearly unknown. The long-time home of Michael Graves (1934-2015), the postmodernist with perhaps the greatest reach – all the way to Walt Disney World and Target shelves – remains in pristine condition in Princeton, New Jersey. It’s owned and preserved by Kean University, and you can visit.

Many architects seek tabula rasa conditions in designing their homes. Graves was different, building his house gradually within a literal self-storage warehouse. Where others once stored surplus belongings in cubes, he saw possibility. Built by Italian stonemasons of hollow clay tile, brick, and stucco, Graves was taken with the warehouse’s look. Karen Nichols, currently principal at Michael Graves and an employee since 1977 (when the firm was Michael Graves & Associates), explains: 'When he went to the American Academy in Rome, he became enamoured of all things Italian. When he found the house, in around 1974, he was dumbfounded that it was a Tuscan vernacular building in terms of both construction type and its formal characteristics.'

Tour the Michael Graves house in Princeton

Graves did not, of course, live in the warehouse’s 44, 10ft lockers. He revamped the interior multiple times, first finishing half of the L-shaped structure in neo-deco style (while the remainder retained a dirt floor for years), then switching to neoclassicism for the second half. He returned and classicised the first half (save for one bathroom, which remains a green and black deco artefact). He rearranged its internal circulation, shifting from a double-loaded corridor plan to a main circulation axis along one side. He carved through several double-height spaces along the way and made some modifications to the exterior. The main entrance is the former truck-loading dock, which likely can't be said of a single other architect's house in history.

The property remains with us in perfect condition thanks to Kean University, whose main campus is located about 40 miles to the north and is home to the Michael Graves College (which includes schools of architecture and design). It acquired the house in 2016 as a gift from Graves’ estate on the condition that it would preserve the property. Universities are undersung stewards of a number of distinguished properties; USC operated the Gamble house in Pasadena for 50 years, until 2019, and its policy of public access continues; Stanford owns Wright's Hanna house in Palo Alto. These sorts of properties often don't have tours you can simply walk up to – but they can be arranged by contacting the institutions, as at Kean.

Michael Graves was an architect of great talent whose quality of work was, for a time, obscured by some of his most successful commissions. He started out as an orthodox late modernist, leagued famously with Richard Meier, Peter Eisenman and Charles Gwathmey among the more formalist 'Whites', against the more contextual and eclectic tastes of the 'Greys', such as Charles Moore and Robert Venturi (the two groups represent different strands of postmodernism in the US). Graves soon morphed radically, moving well beyond grey to become a postmodern harlequin. He was an enormously successful architect in the 1980s and 1990s, eventually building the Swan and Dolphin resorts at Walt Disney World and designing housewares lines for Target and JCPenney.

For all general wishes that architects should venture into popular design, they're often criticised when they do it, and Graves was no exception. The quality of his work has received much-warranted re-evaluation in recent years, with his Portland Building in Oregon City becoming an object of preservation attention, as is, more recently, his excellent Humana building in Louisville, Kentucky, which is soon to be sold by the company of that name. He built many excellent houses, from the Hanselmann House in Fort Wayne, Indiana, to the Plocek House in Warren, New Jersey, but your odds of getting into most of them are low – save for here.

Graves’ own house provides an intensely strong argument for the value of his design philosophy. It is an elegant home that wields classical devices in all sorts of clever ways. It is also as far from an open-plan house as one can get, instead, wielding vistas and subtle shifts in form to lend constant variation. Ian Volner, in his biography of Graves, wrote of his later works’ 'far stronger focus on poche – the walls made thicker and indented with niches and recesses, such that each room had a different spatial character and a different quality of light'.

Nichols relates, 'You'll see a round room, then you'll see a passage, then you'll see something else. He liked the composition of things, he liked the axial view, he liked the terminus.'

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The main passage ends at the library on one side and the dining room on the other; there are numerous excellent internal views throughout the house beyond these. Nichols continues: 'Graves also placed a special emphasis on shaping the ceiling. It's a part of what draws you through and makes you understand the architecture.' This wasn't all. She explains that he even used slightly different shades of white throughout the house to accentuate his other devices. Sometimes, he would also brazen out an architectural point; the exaggerated entasis in living and dining room columns is simply enjoyable.

The result is exceptionally comfortable and even intimate, belying the idea that classical detailing needs to be grandiose. David Mohney, dean of the Michael Graves College at Kean, says: 'What surprised me the most is the domestic scale of the house.' If there are palazzo-like elements within, the whole is really not all that large, containing only three bedrooms. Of the living room, he comments: 'This is the biggest space in the house. You can't fit more than a dozen people in it. You can't fit more than eight people at the dining table. It's all very personal and very domestic.'

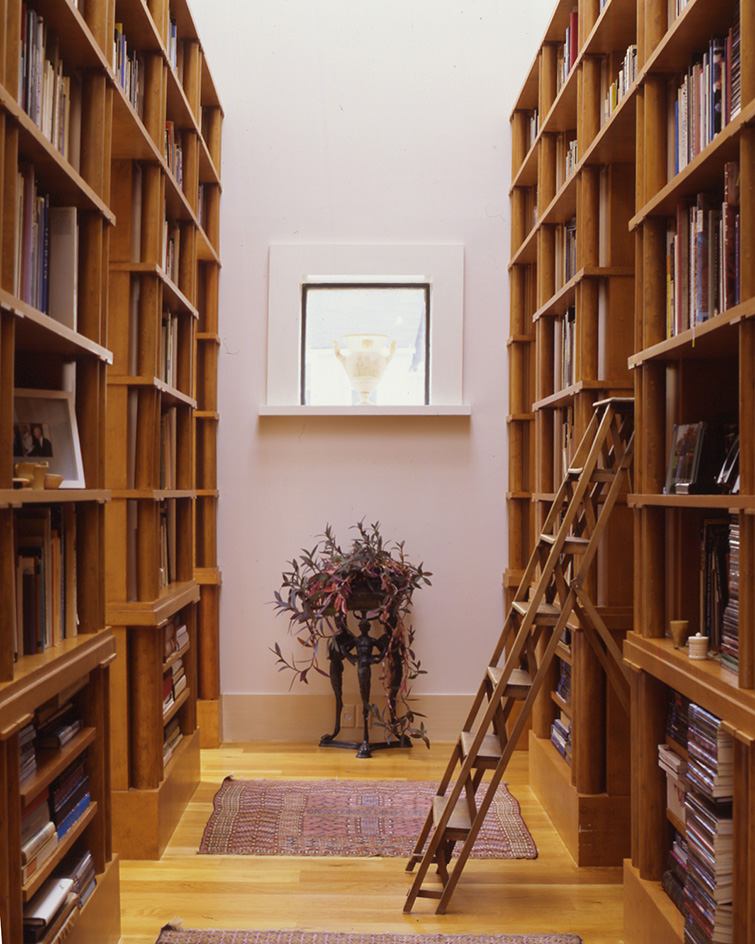

The double-height library at one end of the house is especially striking. Towering bookcases filled with volumes on everyone from Wittgenstein to Christopher Wren to McKim, Mead & White, rise within this skylit space – overlooked by Graves’ own bedroom. There you'll find one of several cheeky design shortcuts. The bookcases look luxe; their supports are actually PVC pipes painted to resemble the grain of bird’s-eye maple. As Nichols quips, 'he was pretty cheap'.

Make no mistake, there are plenty of actually costly items around. The library holds Etruscan pots, including reproductions and examples the architect collected in Italy (while this was still legal). Still, Graves did maintain artificial distinctions about high- and low-cost permissibility in the home.

The living room is an elegant space; there are expensive features and also, humanisingly, those that only pretend to be so. The largest piece of art in the room – which looks like a painting of Psyche at the Bath – is actually framed wallpaper. It also contains Graves’ own copy of a Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot view of Rome. A steady source of interest throughout the property is seeing the architect’s own designs of all sorts of ages. His armchairs for Sunar are there, as are his Alessi kettles and Target clocks and phones. Alabaster lighting fixtures in the living room were bespoke.

Furnishings throughout the house also vary dramatically. There's a Le Corbusier chaise and lounge chair, 19th-century Biedermeier pieces, and also things that it's believed Graves simply bought at local flea markets.

You will chuckle throughout. The candelabras on the dining room table have birds’ feet as a base. Nichols explains: 'The objects are not always [about] serious collecting, sometimes they're just for fun; he was full of wit and whimsy.' Scattered throughout the house are other collectors’ novelties: a range of magnifying glasses and 12 inkwells in the shape of the Temple of Vesta. There are also all sorts of engrossing architectural prints.

The breakfast nook is another double-height, exceptionally bright space studded with busts mounted on brackets, this time with a rather unmistakable influence. Nichols explains: ‘Charles Jencks took us to John Soane’s house and also his Dulwich Picture Gallery. A lot of what you see in the house after [that] was influenced by Soane.’

Stairs are sculptural and topped, naturally, by a bust. Upstairs, the primary bedroom directly overlooks the library; there are no windows or shutters. As Mohney comments: 'There are no barriers to the [view] into the library. Privacy came about not through barriers but through distance.' The main bathroom features five sources of natural light on the sides and above. The guest bedroom is also exceptionally airy.

The second floor features clear traces of Graves’ paralysis due to a spinal cord infection in 2003. His hospital bed remains, as do the necessary alterations: a balustrade around a circular area was removed, a blue-tiled wheel-in shower was converted from a former closet, and an elevator was also installed.

A prime attraction is Graves’ painting studio. Works there might seem like plein-air exercises, but Nichols explains that all of them date from after he was paralysed. 'He often drew from memory or from books. Those are all remembered or imagined compositions influenced by artists like Morandi or Cezanne.'

And that's all, merely skimming the surface of interests to be found in the house. Kean University uses another building on the site for classes and has hopes of providing lodging for more permanent student guides on site in two apartments. The house itself is used occasionally for university meetings. The Michael Graves firm continues to hold a summer picnic in the grounds.

The Michael Graves house in Princeton remains a singular chance to see a postmodern interior when you're not on Larry Ellison's dinner-party invitation list (he owns a Graves house in Malibu). More importantly, you can actually see the architect’s life just as it was lived. Says Mohney: 'This was his own private museum of architecture on his own terms.' And now ours as well.

Access to the Michael Graves house may be addressed to the Michael Graves College at Kean University