Landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander on why it should be easier to be green

A version of this article originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*230)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander is not only a national treasure north of the 49th parallel, but also one of the greatest landscape architects of the modern era. She is the winner of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada’s 2011 Prix du XXe siècle, recipient of the 2012 American Society of Landscape Architects Medal, and a Companion of the Order of Canada. She is a living connection to some of the world’s best-known architects and most important design movements of the last century. Oberlander has a career trajectory that reads like a survey of landscape architecture. From being taught by Walter Gropius at Harvard, to working on social housing projects with Louis Kahn and creating gardens for modernist residences with Arthur Erickson, she has cut a wide and innovative swathe.

An early proponent of rewilding, community consultation, pedestrian-friendly accessibility and creative playgrounds for children, her projects span the globe from the Canadian embassy in Berlin, to The New York Times building, and Erickson’s Robson Square and Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver. At the age of 96, when many of the sustainable practices Oberlander espoused for years have become mainstream, she is still an unstoppable force of nature, working on several projects and doing advocacy work. She is currently designing plantings for Shigeru Ban’s Terrace House in Vancouver (to complement her original designs at Erickson’s adjacent Evergreen Building), and a new publicly accessible roof garden for Moshe Safdie’s Vancouver Public Library.

A narrow walkway above the living room lead to a small balcony overlooking the forest.

She is a passionate proponent of environmental protection and liveable landscapes in urban settings. ‘My passion is to be with nature and introduce people to it from all levels of society,’ says Oberlander over tea in her 1970 Vancouver post-and-beam home, designed with architect Barry Downs to virtually float (thanks to strong concrete pillars) over a ravine. ‘I believe in the therapeutic effects of greenery on the human soul,’ she says. She and her husband won the large lot in the University of British Columbia Endowment Lands when the university held a contest for the best design that would tread most lightly on the semi-wild forested area. Oberlander knew from the age of 11 that she would be a landscape architect.

She grew up in Weimar-era Berlin, narrowly escaping from the Nazis. When her Jewish-German family sought refuge in America, Oberlander enrolled at Smith College, one of the few schools at the time that taught landscape architecture. There, she was classmates with Betty Friedan. The two did not see eye to eye on feminist theory, and while Oberlander admits to having to work ‘twice as hard as a man’, she ‘didn’t think of proving myself – I thought about the project and how I could get it done’.

In 1944 she entered the Harvard Graduate School of Design as one of the first female students. At the time, most American universities taught courses based on old beaux arts techniques, but ‘at Harvard, because of Gropius and Bauhaus, we learned to look at landscape differently – from conception to realisation – as something abstract rather than decorative’. An early career highlight was working with Kahn on a public housing project in Philadelphia in 1951, which informed her two social housing projects in Vancouver in the 1960s, McLean Park and Skeena Terrace, whose community gardens are still thriving today.

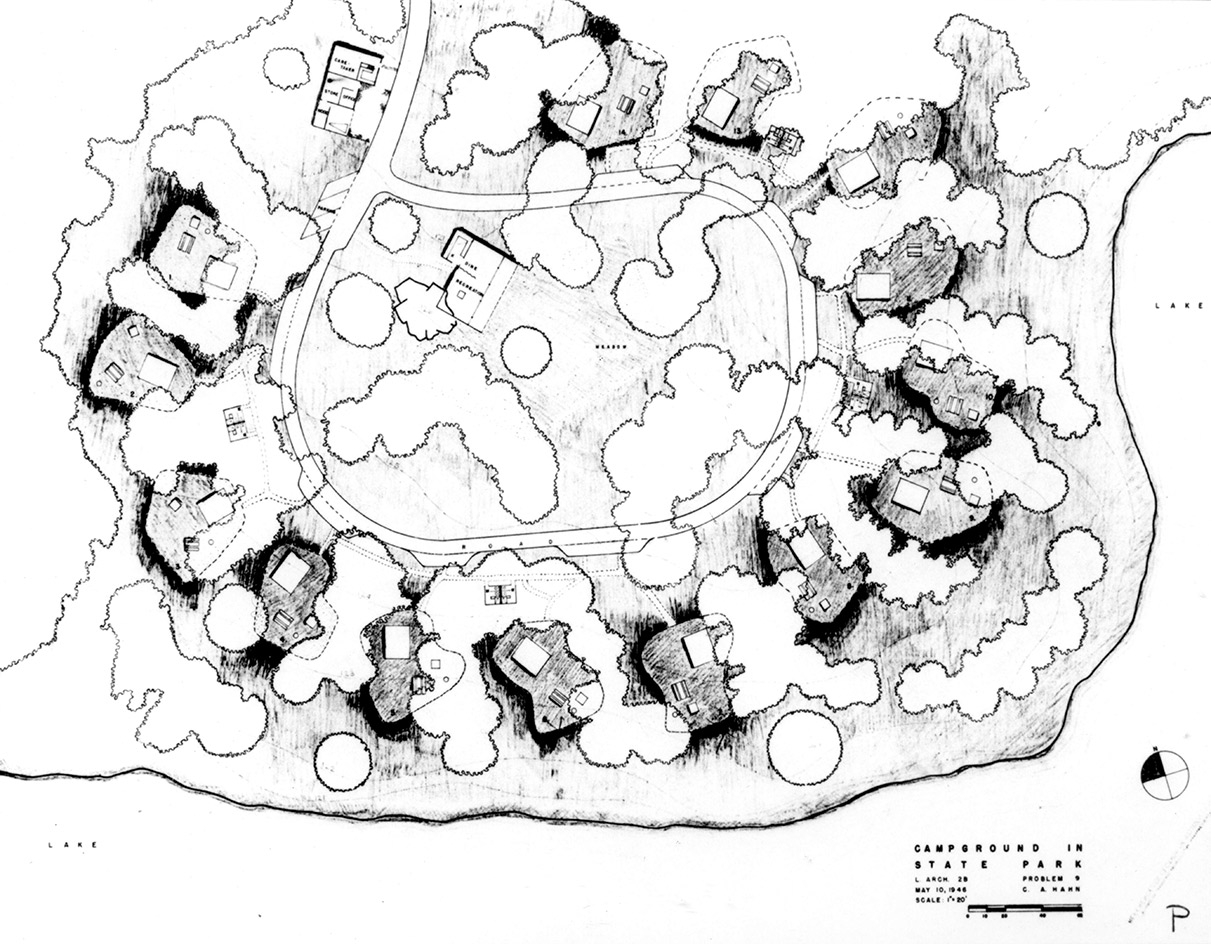

Student project for a state camping ground, 1946. Cornelia Hahn Oberlander fonds, Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

She married fellow Harvard Design School student planner Peter Oberlander, and when he got a job teaching at the University of British Columbia, the family moved to Vancouver in 1953. It was a far cry from her life on the East Coast, where she rubbed shoulders with Kahn and Gropius, but it was a growing city with opportunities and virtually no competition. Her first big commission – a landscape design for the Vancouver home of Dr Sydney Friedman – propelled her local career. Oberlander would create many magical residential landscapes over the years, including the Bagley Wright house near Seattle, which she began working on with Erickson in 1977. Its sculpted meadow was as artfully arranged as the collector clients’ interiors – yet still wild and native.

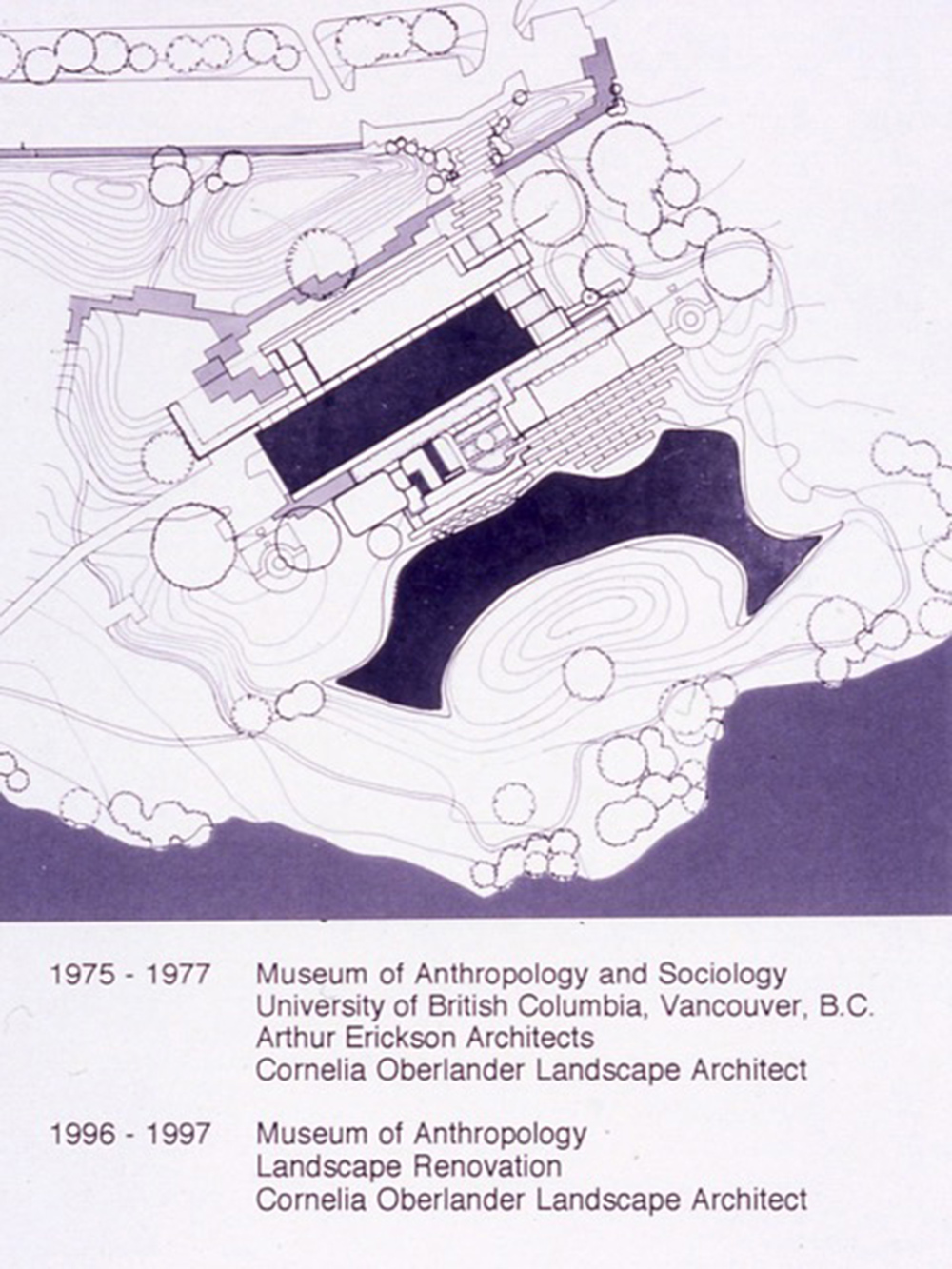

In spite of her well-regarded residential work, Oberlander prefers large urban schemes and her two big Vancouver projects with Erickson – Robson Square and the Museum of Anthropology (where she extended the idea of the First Nations collection into an ethno-botanical meadow) – are her best known projects. Robson Square, commissioned by a progressive provincial government as a ‘building that would put people first’ and completed in 1983, was conceived as an urban oasis – a tower placed on its side, extending over three blocks and comprising a courthouse, government offices and recreational public space.

Concrete pillars enable the house to ‘float’ above a ravine.

‘It’s essentially a park on top of a structure,’ explains Oberlander, who did extensive research on which plants were best suited for the downtown location. Her chosen palette of Japanese maple trees and pines, magnolia and rhododendron, in a syncopated, staggered design, both soothes and elevates the urban aesthetic, offering an abstract yet lush vegetative response to Erickson’s concrete poetry.

The project would cement their mutual admiration and a professional relationship that lasted until Erickson’s death in 2009. Erickson once said that ‘Cornelia is the only person who understands what I’m talking about’, and that she could discern that ‘simplicity’ is ‘not plain-ness’. In spite of the early 1980s vogue for busier plantings, Oberlander heeded Erickson’s advice that ‘there are many shades of green’. Using a less-is-more economy of planting varieties at Robson Square, says Oberlander, resulted in a simple palette that was ‘very effective and therapeutic’. Indeed the complex’s subtle interplay of variegated levels, use of berms that grew into buildings, and roofs into gardens, united landscape and architecture in a singular, elegant form.

Site plan of the Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver, 1977. Cornelia Hahn Oberlander fonds, Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

But Vancouver today has come a long way from the heady days of the 1970s, when the building blocks for Vancouverism – the forward-thinking green city model that became the darling buzzword for international urbanists in the 1990s – were formed. Vancouver in 2018 is in the grips of a housing crisis, and increasingly an ecological one. Oberlander has used the $50,000 she won from the 2015 Margolese National Design for Living Prize to fund a study on how overdevelopment, lack of affordable housing and dwindling green spaces affect people’s mental and physical health. In spite of several public lectures on the topic, City Hall, she says, has yet to respond. But Oberlander remains a true believer in the power of landscape architecture to save the world, and sees an innate connection between social justice and good design. ‘Beauty is important,’ she affirms. ‘It unites people and makes something meaningful to the user.’

She ultimately sees her calling as a kind of healing art, and like the concept of ‘invisible mending’ expressed in her Inuvik school in the Northwest Territories, which reintroduced native plantings after nurturing them in nurseries, she also helps to heal cities. ‘My design is therapeutic for busy people in the city who use only electronic devices,’ she pronounces. ‘Just look out at my garden. You can’t even see the street. Isn’t it peaceful?’ And with that, Oberlander is off to preach her gospel of enlightened urban design to City Hall, where the mayor’s office would do well to pay heed to the wise landscape architect who helped build a city that still dreams of being truly green.

A version of this article originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*230)

The living area, with a bold yellow wall, inspired by Bauhaus aesthetics

The first-floor hallway and open-plan lounge are flooded with natural light thanks to a series of large skylights

Like the rest of the house, Oberlander’s study features glass walls with views of the surrounding local flora, which has grown to form a thick green mantle since the house’s completion in 1970

The elongated pavilion features a post-and-beam frame clad in locally sourced cedar, and Mies van der Rohe-inspired Cubist overhangs

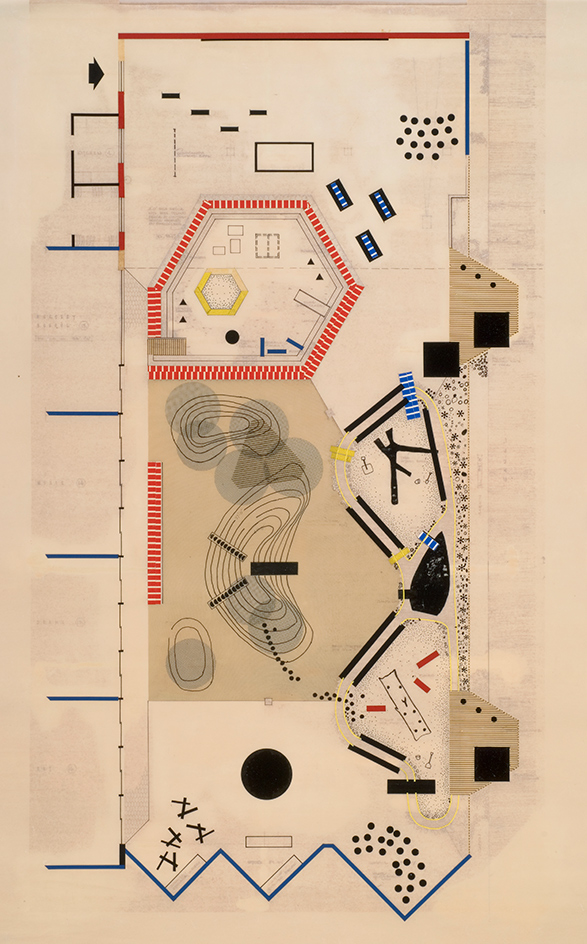

Landscape plan of the Canadian Pavilion playground, Expo 67, Montréal. Cornelia Hahn Oberlander fonds, Collection Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.