Revisiting the concrete architecture of Belgian icon Juliaan Lampens

Once the lonely passion of a few devotees, the concrete architecture of Belgian architect Juliaan Lampens is a revelation; just don't call him a brutalist

Misha de Ridder - Photography

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Those, like us, who have a soft spot for crude concrete architecture, will love the work of Juliaan Lampens (1926-2019). The powerful concrete roughness of the Belgian architect's volumes is inescapable when you walk past two of his best known buildings, both near Ghent: the Chapel of Our Blessed Lady of Kerselare, in the village of Edelare, and the Van Wassenhove house in Sint-Martens-Latem.

However, digging a little deeper into Lampens' life and work, it quickly becomes apparent that there is more to his architecture than brutalism by numbers. Belgian curator Angelique Campens has been studying Lampens' work since her university years and knew him well. The architect had a reputation for being reserved, keeping his business to himself to the point of avoiding contact with colleagues. He didn’t even travel much, reveals Campens. ‘But he had a lot of books. He admired Oscar Niemeyer and was influenced by Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe.' He may seem to have lacked the desire for architectural pilgrimage, but Lampens practised non-stop from his base in Eke, East Flanders, from 1950 until his last work was built in 2002 – creating a legacy of about 50, mostly residential, projects, including the chapel and Eke library.

Lampens was born in 1926 in De Pinte and grew up in nearby Eke, the son of a cabinetmaker. After working as a technical draughtsman, he studied architecture in Ghent and set up his own firm straight after graduation, kick-starting it with commissions from his father's middle-class clientele. While following a more conventional design style at first, he nurtured an interest in modernism. 'His visit to the 1958 World's Fair in Brussels was a turning point for him,' Campens explains. 'Shortly after that, his designs changed drastically. He thought that Le Corbusier was too sculptural, and Mies too structured, but he wanted to combine the two.'

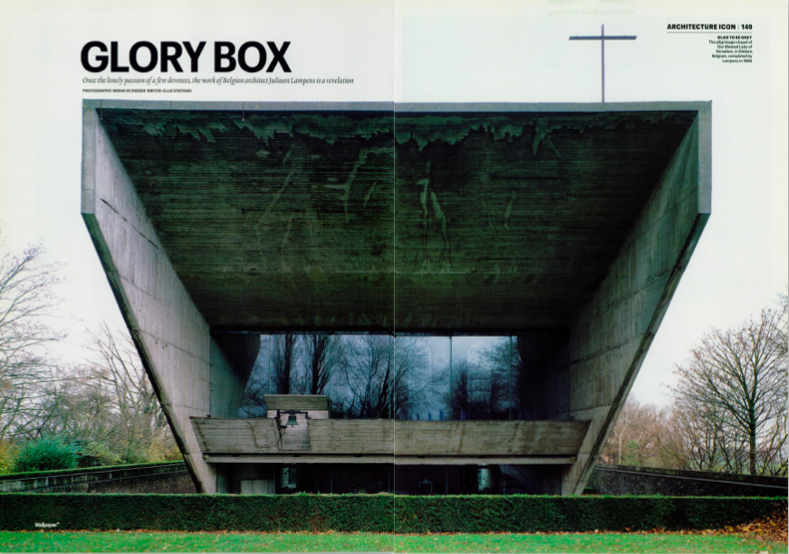

Spread from the original feature in Wallpaper* 133, April 2010, featuring the Chapel of Our Blessed Lady of Kerselare, in the village of Edelare

Lampens' first modern design was his own house and office in Eke, built in 1960. The house, a simple low box with a strong horizontal concrete slab roof and wooden details, was a taste of things to come. Testing the idea of lightness, the architect created the structure with almost no load-bearing walls, based on a steel-column grid. Glass-enclosed apart from a brick wall concealing it from the street, the house connects visually with the outdoors at the back and is largely open-plan inside, with bare brick and concrete on show. For the region at the time, Lampens' approach was radical. Privacy from the street, a connection with the natural environment, the use of exposed raw materials and an open-plan interior all became recurring themes in his work. Lampens also paid special attention to smaller concete architecture details, such as the roof's drains, which he described as 'functional ornaments'.

The commission for the Chapel of Our Blessed Lady of Kerselare followed soon after the completion of Lampens' house. However, the design with which he won the 1961 competition – with Professor Rutger Langaskens, one of his former teachers – was very different from what you see today. Upon winning, Lampens reworked the building, making it so altered from the original and so alien to the neighbourhood that during the concrete casting, passers-by thought it would be a silo. Despite this, and with the incumbent pastor's support, the high-ceilinged chapel – resembling a giant concrete skip – opened in 1966. It featured bespoke concrete benches (currently removed), a large glass wall and a central concrete skylight, while the protruding mono-pitched roof provided outdoor shelter for the congregation.

It was the chapel's large untreated surfaces that led many to label Lampens a follower of brutalist architecture, a tag he has never accepted. 'He never felt part of a group,' Campens stresses. The chapel and his Eke house were landmarks in Lampens' career. Part of his aloof, albeit good-natured, character is reflected in the esoteric, yet sturdy and unexpectedly open designs; street-shy, they are welcoming once you're inside. Certainly, they gained him many new commissions.

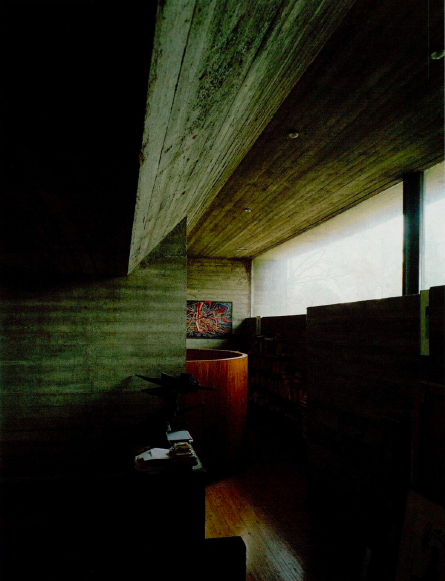

The Van Wassenhove house in Sint-Martens-Latem. Spread from the original feature in Wallpaper* 133, April 2010

Among these was the Van Wassenhove residence, completed in 1974. School teacher Albert Van Wassenhove, admiring the Kerselare chapel, asked Lampens for a similar house. In response, and taking into account the plot's limited views, the architect created an irregular rough-cast concrete volume, blind from two sides and semi-sunken into a hill. For the flowing interior, as with other projects, Lampens designed furniture – chairs, tables and chaises longues – all simple and mainly wooden.

Lampens' most daring work is the Vandenhaure-Kiebooms house in Huise, completed in 1967. The client, Gerard Vandenhaute, hoped for a house that pushed the envelope. His wish was granted. Designed along Lampens' usual lines – a minimal, one-level glass box topped off with a thick concrete flat roof – the house is pillar- and wall-less inside; even the bathroom is open to the rest of the interior, with privacy afforded only by a shoulder-height cylindrical concrete partition. In a play of transparency and openness, the only other fixed component is the kitchen. The roof stands on a solid, street-facing concrete wall and two steel pillars on the opposite side.

Sketching everything from tiny details to larger concepts, Lampens produced hundreds of drawings throughout his career, signing every one. Still, he never cherished paper architecture. 'He called it “embryonic” architecture. For him, drawings were secondary. Built work remained the important thing,' Campens says. Today, these drawings are held at Eke library, where the Juliaan Lampens Foundation takes care of his archive, run by, among others, his son Dieter Lampens and Campens.

Lampens' experimental, concrete architecture work remains largely unexplored. A group exhibition in Brazil he participated in years ago is probably its only appearance outside Belgium. But there remains a devoted local following for his idiosyncratic designs. Tellingly, owners of Lampens’ houses are known to have lived in them for a long time. Campens’ monograph about the architect was published in 2010, and in 2012, the Van Wassenhove house was bequeathed to the University of Ghent. Now on long-term loan to the museum Dhondt-Dhaenens in Deurle, it gained monument status in Belgium in 2017.

A version of this article was first published in the April 2010 Issue of Wallpaper* (W* 133)

Kitchen and dining at the Van Wassenhove House

Sleeping area at the Van Wassenhove House

Drainage detail outside the Van Wassenhove House

The pilgrimage chapel of Our Blessed Lady of Kerselare in Edelare

Skylight above the altar at the pilgrimage chapel of Our Blessed Lady of Kerselare in Edelare

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).