All hail the power of concrete architecture

‘Concrete Architecture’ surveys more than a century’s worth of the world’s most influential buildings using the material, from brutalist memorials to sculptural apartment blocks

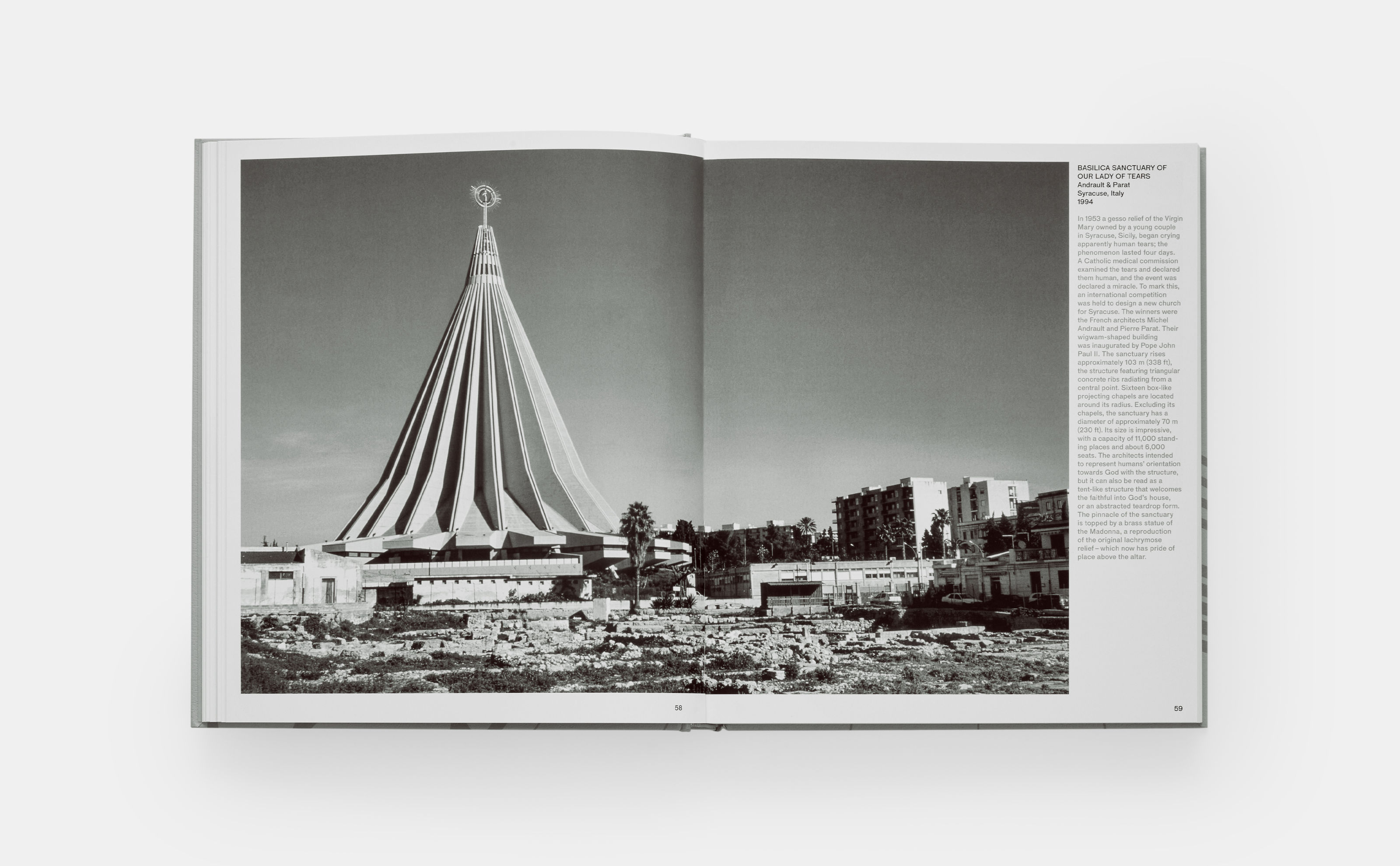

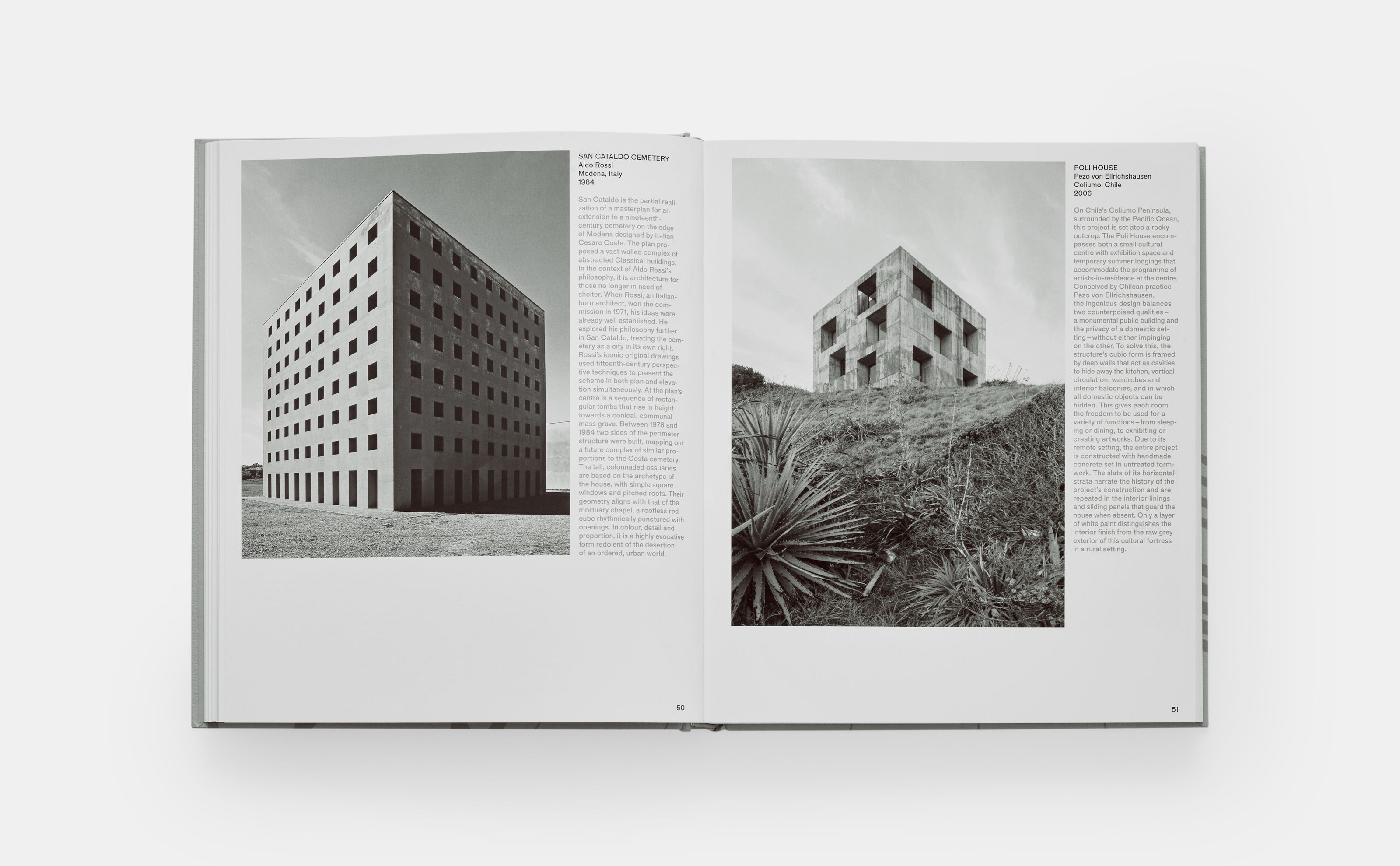

If ever a book was designed for a coffee table, it’s this hefty volume on concrete. Pitched at the diehard brutalist who desperately wants to convert others to their cause, Concrete Architecture makes its case through a feast of black and white imagery of the very best concrete architecture from around the globe, spanning the material’s earliest usage right up to the present day.

Monument to The Fallen Soldiers of The Kosmaj Partisan Detachment, Vojin Stojić, Gradimir Medaković, Belgrade, Serbia, 1970

Concrete Architecture: thrilling and divisive

Concrete can be seen as problematic, not least because its use often results in the most divisive of all architectural aesthetics, brutalism, but also because the material itself – though long-lasting and hard-wearing if mixed with sufficient care and attention – is extremely carbon intensive. Not only that, but unwanted concrete is tough and pricey to prise off the face of the earth once it’s no longer required.

Spread from Concrete Architecture, published by Phaidon

That’s not a problem with any of the 300-plus projects featured within this architecture book. Although many have had ups and downs in their popularity, the pendulum of public taste has largely swung behind the preservation of even the most pugnacious of concrete structures. That said, some of the featured projects take the definition of architecture to its limits and perhaps reveal why the material could be so reviled.

Innovation Centre, Pontifical Catholic University Of Chile, Elemental, Santiago, Chile, 2014

We’re thinking in particular of the MP4 L’Angle Tower on the island of Alderney, a Second World War-era German fortification, designed by the Organisation Todt as part of the Nazi occupation of the Channel Islands. Offensive, oppressive and malignant, it also retains a dark sculptural power, something that architects in the decades that followed sought to parlay into buildings that served progressive society, not fought against it.

MP4 L’Angle Tower, Organisation Todt, Alderney, Bailiwick of Guernsey, Channel Islands, 1942

Hence concrete became beloved of ecclesiastical architects, as well as the designers of concert halls and apartment buildings, monuments, bridges, libraries, schools, hospitals and offices.

Memorial and Cultural Centre, Marko Mušič, Kolašin, Montenegro, 1979

Some of the best-known architects of the modern era shaped their reputations in concrete; it remains the preeminent component of infrastructure projects around the world.

Timmelsjoch Experience Pass Museum, Werner Tscholl, Timmelsjoch, Austria, 2010

Nevertheless, its detractors point to its environmental impact and divisive aesthetic, perhaps having never managed to shake off the brutalist association with the bunker. Concrete Architecture is perhaps the best chance you'll get to try and change their mind.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Spread from Concrete Architecture, published by Phaidon

'Concrete Architecture,' Phaidon Editors, with Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin, Phaidon, £59.95

Phaidon.com, also available from Amazon

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.