Bauhaus-inspired university campus in Nigeria designed as a social stage

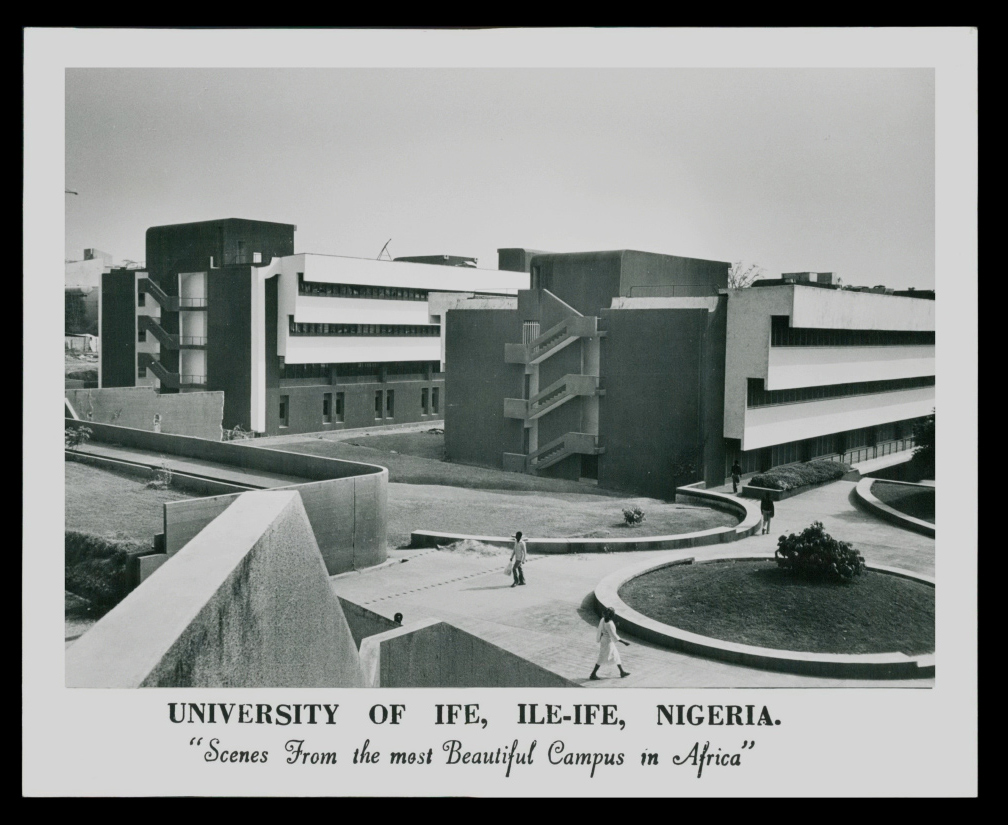

A documentary titled Scenes from the most beautiful campus in Africa – a film about the Ife Campus commissioned for the Bauhaus centenary celebrates the Obafemi Awolowo University in Nigeria. A symbol of Nigeria's Independence from Britain in 1960, the modernist university was a product of politics, design and climate, yet its main priority was always its function as a social stage for education and community.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

On the occasion of the Bauhaus centenary, architect and historian Prof. Dr. Zvi Efrat was commissioned to create a short documentary by Germany’s ‘Bauhaus Imaginista' travelling exhibition programme, with the aim of uncovering a lesser known Bauhaus building that would demonstrate how Bauhaus ideas had spread across the world. Efrat picked the Obafemi Awolowo University located in Osun state, Nigeria. Originally known as the University of Ife, the campus was designed by Bauhaus graduate Arieh Sharon together with a team of Nigerian architects including Lagos-based architect A.A. Egbor between the 1960s and 1980s.

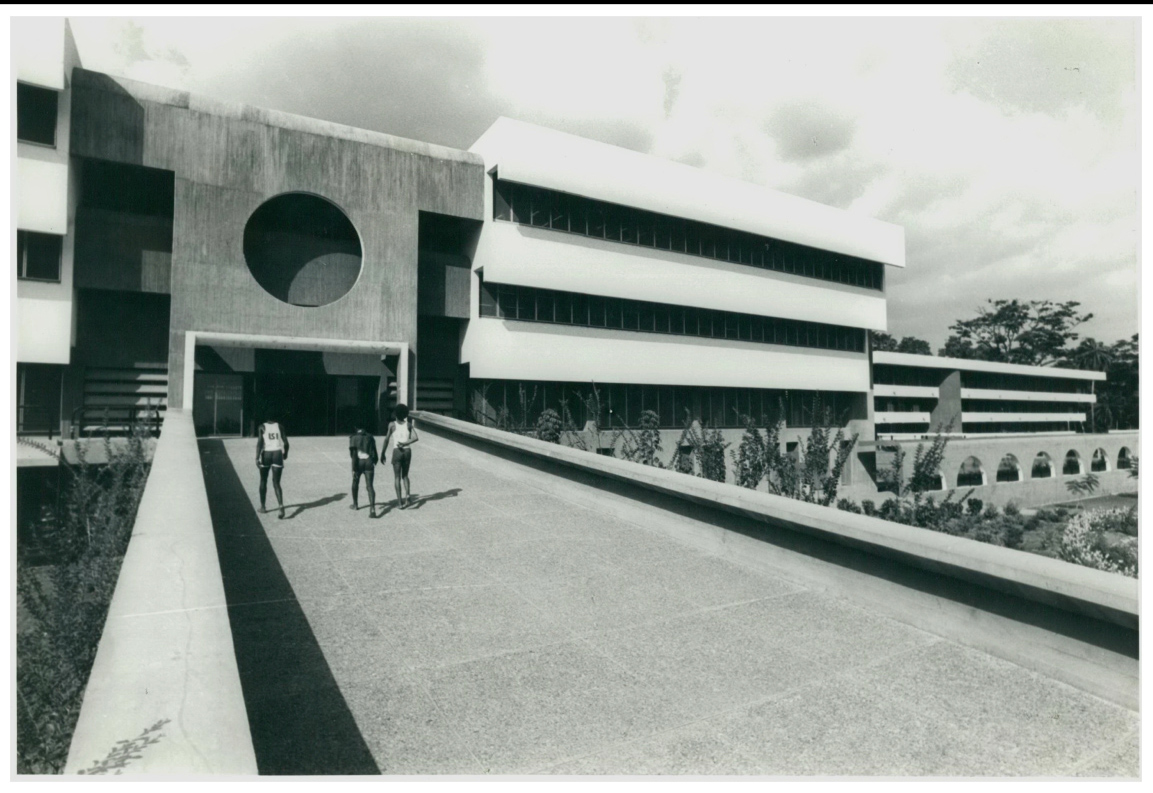

Efrat’s film takes a social journey through the university site – into covered outdoor spaces where students gather informally, past concrete buildings connected by pathways, up stairs and through courtyards where air circulates, light penetrates and shade cools. With his lens, Efrat wanted to capture how Bauhaus design and theory was combined with climactic and cultural specificity – most importantly with continuing success today.

Still from the documentary picturing students sitting in the circular alcoves

The layers of the university’s history, and its meaning today, are as complex as its layered levels of architecture. The building represents an important moment in time for Nigeria as a symbol of its 1960 independence from Britain, while also at play is the national relationship between Europe, Israel and Nigeria as well as Arieh Sharon’s Bauhaus education. Even the act of Efrat’s own documentary-making is critical to the neccesary post-colonial conversation. As an architect, academic and author, Efrat was well positioned to approach all of these angles through his documentary.

The commission for the university project arose within a decade when political relations between Nigeria and Israel were aligned. ‘The year of 1960 was the moment of independence for Nigeria, when it was decolonized from the British. The country wanted to build a university that would represent Nigeria’s own ideas of democracy. They didn’t want to use British architects, nor architects of European powers, but Israel was also considered as a country that also had been decolonized a decade before by the British. Later however, 10 to 15 years on, Africa would reject Israel politically, and in the 1970s it would be not welcome,’ says Efrat.

Modernism wanted to be international, but in this campus, we see the influence of local culture

Political events such as the rise of Hitler in Germany and the Independence of Israel from British mandate in 1948, lead to architect Sharon designing the University of Ife building. Sharon was studying architecture at the Bauhaus in Dessau under Hannes Meyer where he lived with his wife and daughter in one of the Master’s Houses, when in 1931 he was forced to leave to Palestine. There he became the lead architect of the Labour Unions under British mandate, designing communal workers houses in the Bauhaus style.

After the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, Sharon became the state architect in charge of master planning: ‘In 1950 Israel published a master plan, I call it the mould of Israel, which determined the shape of the state that we have today. Sharon is a very important figure in Israel, where he designed a lot of new towns and hospitals,’ says Efrat.

Still from the documentary showing people sitting beneath to extended canopies

‘In the 1950s, the focus for Israel was looking inwards, but after that, in the 60s, they were looking for new frontiers and part of this was establishing new relationships with developing countries. Israel was going through a period of diplomacy, sending agricultural and military aid, but also sending skills such as engineering and architecture, specially in Africa.’

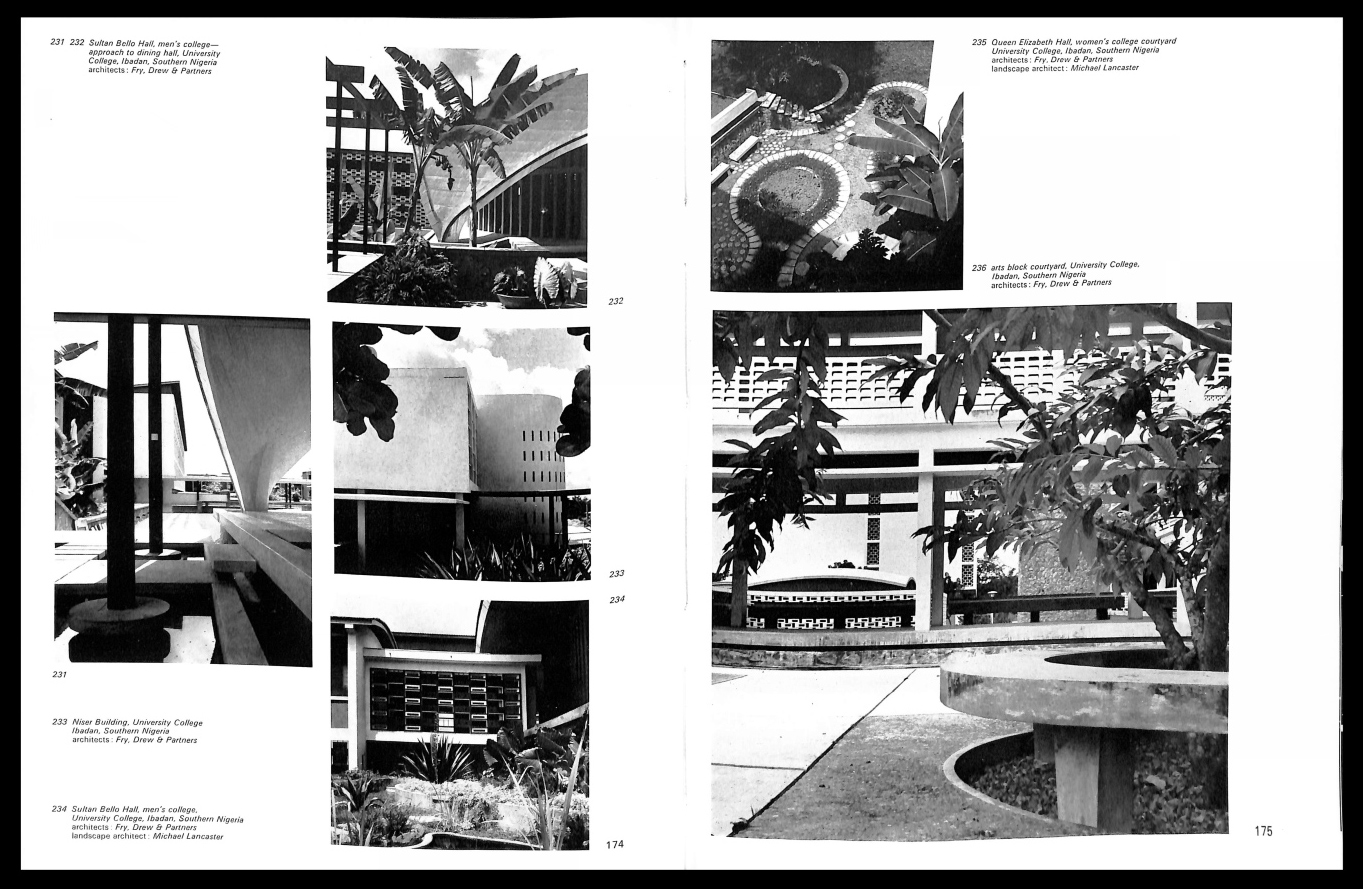

For Sharon, who passed away in 1984, the university was the largest project of his later years. He took it very seriously, explains Efrat, and travelled as far as Mexico City to search for a model for the building: ‘Alongside the local team of architects and the local academic leaders, Sharon was really working on a campus that would fit the Nigerian climate and culture. Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew set up the “Tropical architecture” department at the AA, but it mainly dealt with the skin and envelope of the building – perforating the outer walls or creating screens – but it was just the same boxy architecture, but with better shading devices and ventilation.

Archive document and photography of the campus

‘Sharon [and other architects on the project] didn’t use their [Fry and Drew’s] approach, but invested in a new tropical system. They inverted a pyramid, using the upper floors to shade the lower floors, freeing up the ground floor to open corridors, columns and patios. The landscape beneath the building is continuous and a very smart positioning of the buildings allows for the free circulation of air through the buildings, an architecture without doors. Yet it also protects people from heavy rain, through balconies and canopies, and protects from the harsh sun, as well as constantly being ventilated. Today, it’s what we call passive architecture.’

Instead of a Bauhaus aesthetic, as seen in education buildings such as the Bauhaus School in Dessau or the ADGB Trade Union School in Bernau, the Ife University Campus strikes a conversation up between modernism and brutalism. ‘It’s not a thin building with glass walls, but a lot of the ideas of Bauhaus are very much there,’ says Efrat.

‘First of all, it’s an architecture that is a tool to create a better human habitat and bring about social change. Also more specifically, Hannes Meyer, second director of Bauhaus, and Sharon’s mentor, really emphasized the more scientific approach to architecture, where architecture is not just an aesthetic whim, but based on a rational study of climate and physical conditions. Sharon followed this, and based his design on several ecological studies. Modernism wanted to be international, but in this campus, we see the influence of local culture – we see decoration on the walls and shapes that correspond to Yoruba culture.’

Still from the documentary showing the layers of the architecture in use

There was, however, much that could not be understood about the building from its history or its design, which Efrat discovered when he arrived to start work on the documentary. ‘I thought I had a certain narrative in mind, but I realised I had all sorts of Western colonial, post-colonial and smart academic preconceptions,’ says Efrat.

Yet from working with a local team of photographers living in Lagos, and through his interviews with professors and students, his ideas evolved much further: ‘The film became about the perspective, capturing the everyday life of the campus, the spontaneity it creates through its form and a description of the place by the people who use it. People were the main subject matter of the film.'

Still from the documentary showing people looking out from circular openings in the walls of the building

He continues: ‘The first time we came to film, suddenly we heard drums and music, and a political campaign for a governors’ election came out of the blue through the campus, it was a huge party to welcome the candidate. The second time, we heard a more melancholic brass music, and a procession of drummers and dancers, it was a funeral processing through the open ground floor of the university. Down the covered passages, everything is visible, the campus is a stage for daily performances, musical events and academic activity, and that’s just normal, its a very lively situation.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Archive documents showing examples of Fry, Drew & Partners’ examples of tropical architecture and landscaping

You’ll see from the stills, or if you get a chance to see the documentary, how the building is designed like an eco-system, making space for every type of activity – quiet moments for reading, long corridors for a walk, courtyards for communal gathering, cover for rainy days and open air for mild ones. The auditorium, for example, seats 3000 people, yet it is left open and small classes of students bring in boards and books to study in small groups or sit informally together.

The University of Ife was born of a moment in history where colonial powers, nationalities, skills, climates, people and movements passed like ships and collided. Yet, today, as the Obafemi Awolowo University, the building has its own identity, carved through daily function and use by the people who populate it. The latter is the portrait that Scenes from the most beautiful campus in Africa – A film about the Ife Campus catches in motion.

INFORMATION

For more information, visit the Bauhaus Imaginsta website

Harriet Thorpe is a writer, journalist and editor covering architecture, design and culture, with particular interest in sustainability, 20th-century architecture and community. After studying History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and Journalism at City University in London, she developed her interest in architecture working at Wallpaper* magazine and today contributes to Wallpaper*, The World of Interiors and Icon magazine, amongst other titles. She is author of The Sustainable City (2022, Hoxton Mini Press), a book about sustainable architecture in London, and the Modern Cambridge Map (2023, Blue Crow Media), a map of 20th-century architecture in Cambridge, the city where she grew up.