Camera ready: unseen works by Irving Penn get an airing in Dallas

To many, Irving Penn is known as the man behind the lens of several iconic fashion images – from the 1950 photo of his wife, model Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn in a Rochas Mermaid gown, to the 1995 photo of a bee sitting atop a pair of rosy – (almost) literally bee-stung – lips. But Penn also had a creative side away from fashion, capturing urban social snapshots in the United States and tribal women in Africa. Now, for the first time, many of his unseen works are on display at the Dallas Museum of Art in ‘Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty’, the first comprehensive retrospective of his work in two decades.

‘He saw beauty as an absolute value,’ says Sue Canterbury, the Pauline Gill Sullivan associate curator of American art at the Museum. ‘You see this thread running throughout his work, whether it’s a fashion model in Paris, or a biker in San Francisco with Hell’s Angels, or the people he shot in his travels in Peru, New Guinea, or Morocco.’

The exhibition, which features around 140 photographs, takes viewers through what Penn saw from behind his lens, from early street scenes of Philadelphia and New York in the late 1930s, to his images of the residents of Cusco, Peru in the 40s and native Dahomey girls in the late 60s. Also included are famous portraits of artists and intellectuals like Salvador Dalí and Langston Hughes, and Penn's surveys of the post-Second World War European working class.

As the show leads on to his fashion work, Penn’s gift for fashion photography becomes evident in the way the silhouettes of the clothes become sleek sculptures. ‘Before he stepped in, fashion shoots were situational,’ says Canterbury. ‘You created a tableau vivant. He changed it by creating these wonderful plain backgrounds. The result is that there is no distraction from the clothes.’

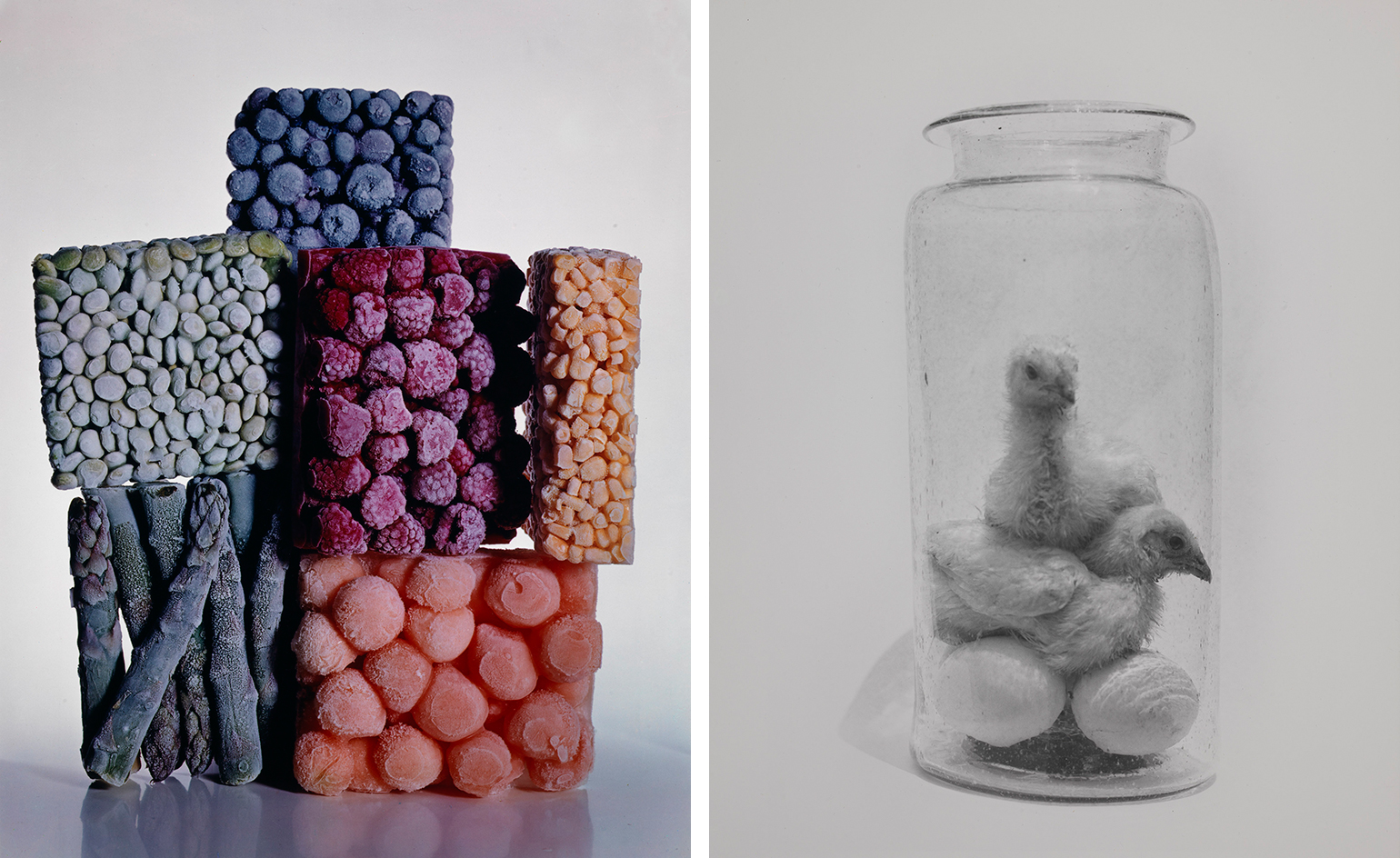

Penn was a master of composition, darkroom developing and still life, and had an eye for making anything beautiful – even the flattened street trash he photographed in platinum in the 1970s. He saw beauty in everything, even boxes of frozen produce (photographed in 1977). ‘It was very innovative, the way that he [thought], and also the way that he saw things could be shot,’ concludes Canterbury.

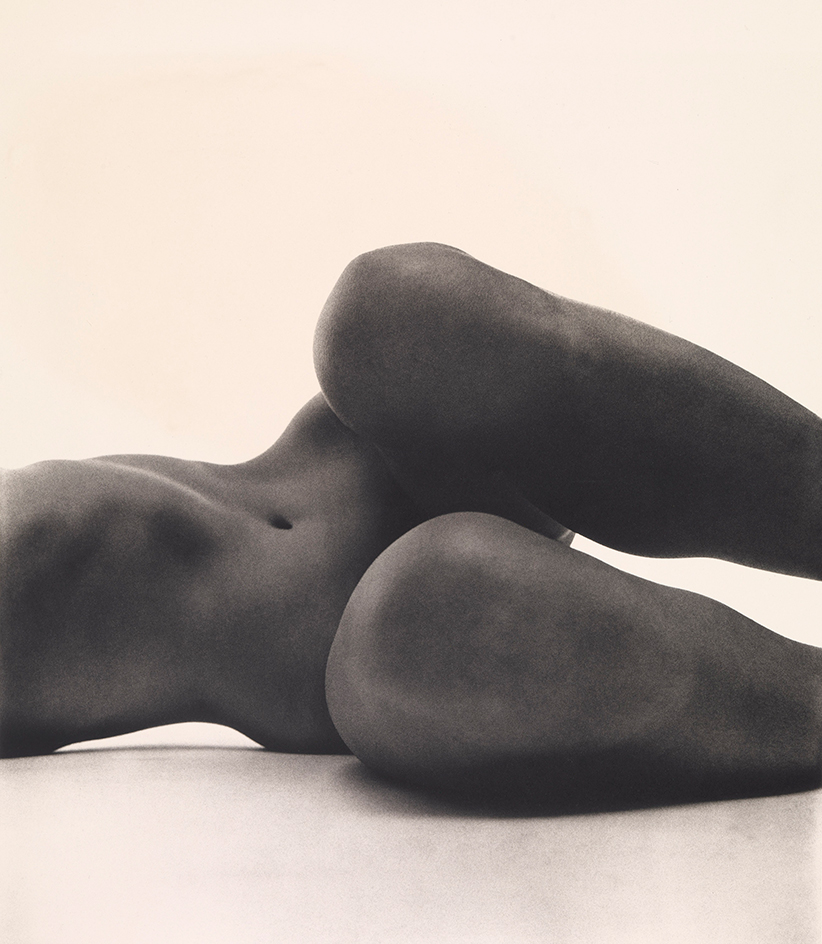

'He saw beauty as an absolute value,' says Sue Canterbury, the Pauline Gill Sullivan associate curator of American art at the Dallas Museum of Art. Pictured: Nude No. 58, c.1949–1950

The exhibition, which features about 140 photographs, takes viewers through what Penn saw from behind his lens. Pictured: Bee, 1995

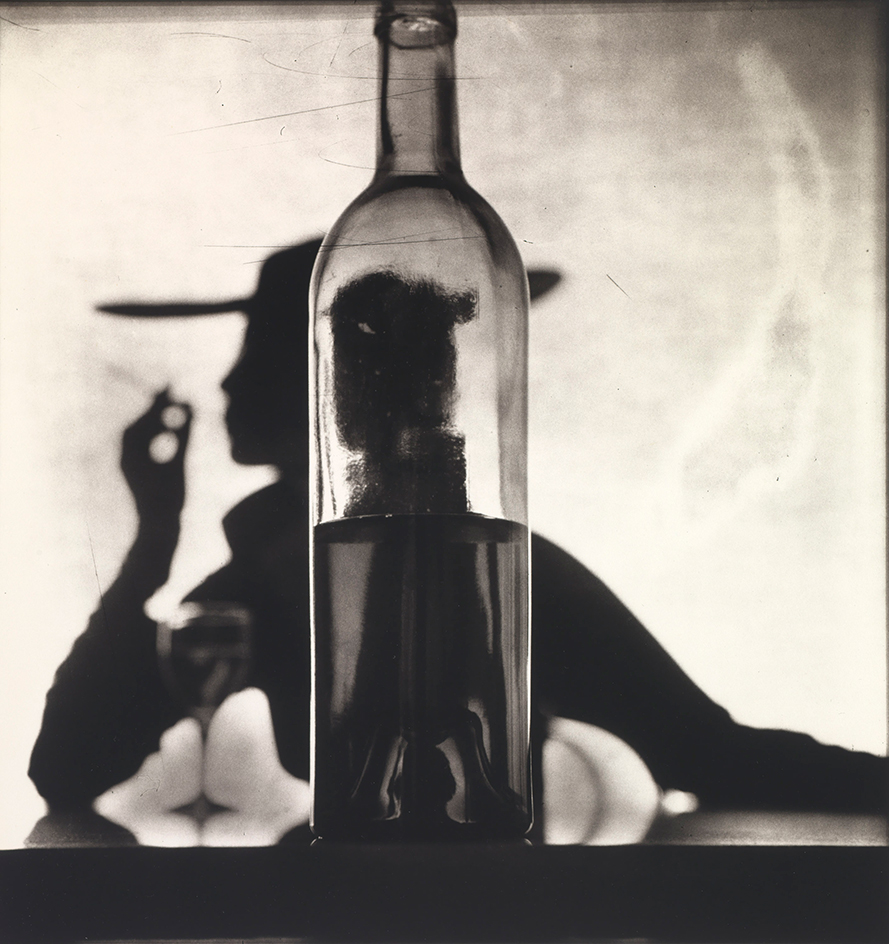

As the survey leads on to his fashion work, Penn’s gift for fashion photography becomes evident, here in the way the silhouettes of the clothes become sleek sculptures. Pictured: Girl Behind Bottle (Jean Patchett), 1949

The exhibition also features some of Penn's most iconic images, including Woman in Moroccan Palace (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn), 1951 (pictured)

Penn was a master of composition, dark-room developing and still life, and had an eye for making near anything beautiful. Pictured: Bedside Lamp, 2006

'It was very innovative, the way that he [thought], and also the way that he saw things could be shot,' says Canterbury. Pictured left: Frozen Foods, 1977. Right: Chicks in a Jar, Mexico, 1942

‘He saw beauty as an absolute value,’ says Canterbury. ‘You see this thread running throughout his work, whether it’s a fashion model in Paris, or a biker in San Francisco with Hell’s Angels, or the people he shot in his travels in Peru, New Guinea, or Morocco.’ Pictured: Sitting Enga Woman, New Guinea, 1970

INFORMATION

’Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty’ is on view until 14 August. For more details, please visit the Dallas Museum of Art’s website

Photography courtesy of the Irving Penn Foundation and the Dallas Museum of Art

ADDRESS

Dallas Museum of Art

1717 North Harwood Street

Dallas, Texas

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Ann Binlot is a Brooklyn-based freelance writer who covers art, fashion, design, architecture, food, and travel for publications like Wallpaper*, the Wall Street Journal, and Monocle. She is also editor-at-large at Document Journal and Family Style magazines.

-

Premium pocketable audio scales up with the new SP4000 from Astell&Kern

Premium pocketable audio scales up with the new SP4000 from Astell&KernThe Astell&Kern A&ultima SP4000 is a serious piece of audiophile equipment, a high-res portable player that offers endless ways to shape your listening experience

-

The ultimate amenity in this Canadian apartment building? A trio of scene-stealing restaurants

The ultimate amenity in this Canadian apartment building? A trio of scene-stealing restaurantsPart of Citizen on Jasper, a new residential tower, Va!, Olia, and Mimi offer a thrilling day-to-night dining experience

-

These sculptural mirrors embody the relaxed spirit of the Med

These sculptural mirrors embody the relaxed spirit of the MedPhotographed in a Mallorcan residence designed by local studio Munarq, these new sculptural mirrors by New York furniture company Ready To Hang are inspired by the sea

-

Richard Prince recontextualises archival advertisements in Texas

Richard Prince recontextualises archival advertisements in TexasThe artist unites his ‘Posters’ – based on ads for everything from cat pictures to nudes – at Hetzler, Marfa

-

The best Ruth Asawa exhibition is actually on the streets of San Francisco

The best Ruth Asawa exhibition is actually on the streets of San FranciscoThe artist, now the subject of a major retrospective at SFMOMA, designed many public sculptures scattered across the Bay Area – you just have to know where to look

-

Orlando Museum of Art wants to showcase more Latin American and Hispanic artists. Do you fit the bill?

Orlando Museum of Art wants to showcase more Latin American and Hispanic artists. Do you fit the bill?The Florida gallery calls for for Hispanic and Latin American artists to submit their work for an ongoing exhibition

-

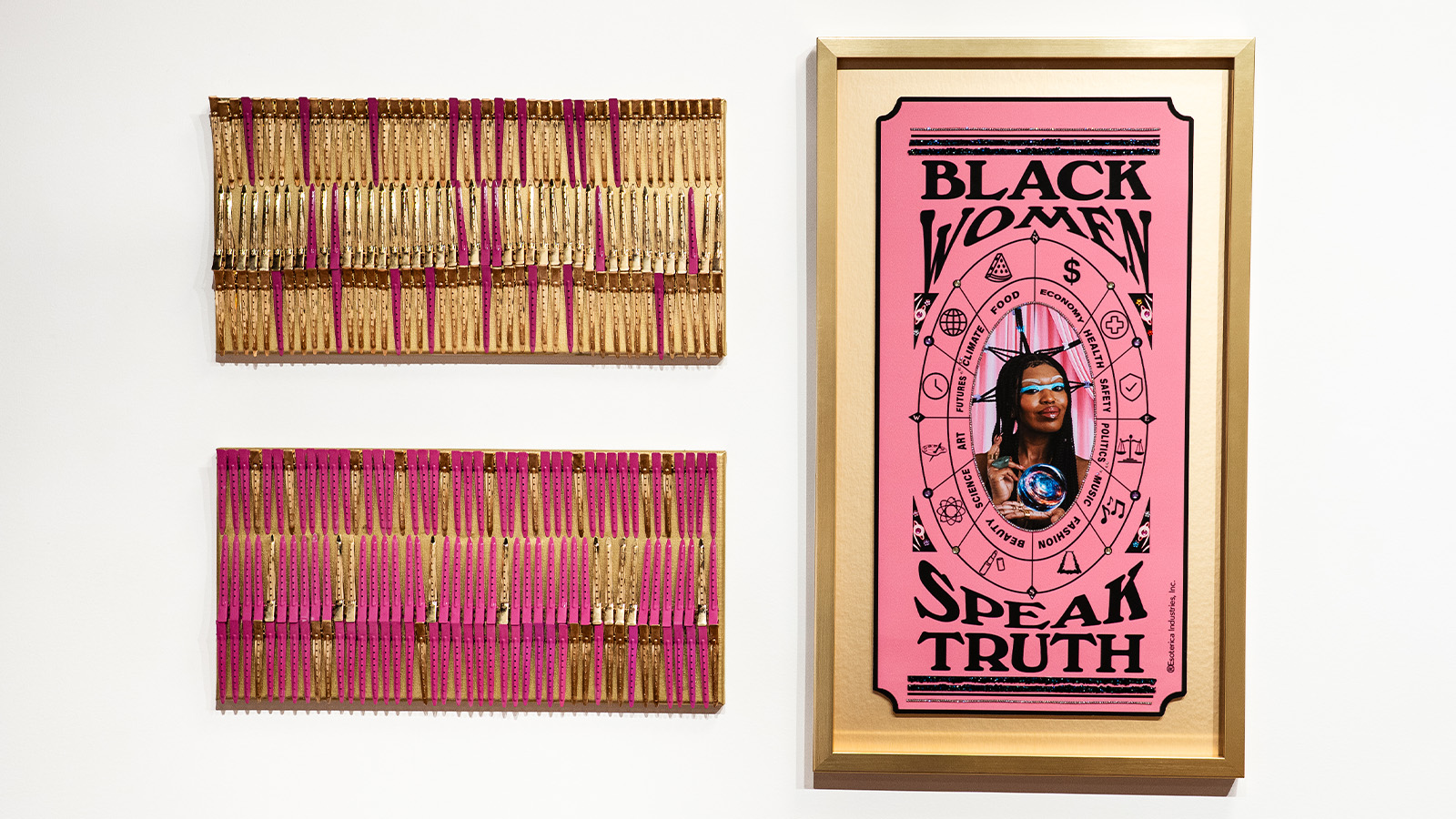

The spread of Butter: the Black-owned art fair where artists see all the profits

The spread of Butter: the Black-owned art fair where artists see all the profitsThe Indianapolis-based art fair is known for bringing Black art to the forefront. As it ventures out of state to make its Los Angeles debut, we speak with founders Mali and Alan Bacon to find out more

-

Steve Martin wants you to visit The Frick Collection

Steve Martin wants you to visit The Frick CollectionThe actor has appeared in a video promoting New York’s newly renovated art museum

-

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raising

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raisingAt Art Omi sculpture and architecture park, NY, Besler turns barn raising into an inclusive project that challenges conventional notions of architecture

-

The dynamic young gallerists reinvigorating America's art scene

The dynamic young gallerists reinvigorating America's art scene'Hugging has replaced air kissing' in this new wave of galleries with craft and community at their core

-

Meet the New York-based artists destabilising the boundaries of society

Meet the New York-based artists destabilising the boundaries of societyA new show in London presents seven young New York-based artists who are pushing against the borders between refined aesthetics and primal materiality