The Trip: explore Helsinki’s saunas, shipyards and side streets

Weekly at Wallpaper*, ‘The Trip’ takes you on a detailed tour of an under-explored town, city or territory, direct from your living room. This week’s feature is from our July 2012 issue (W*160), focusing on the then World Design Capital of Helsinki. There, photographer Jonathan de Villiers and writer John-Paul Flintoff witnessed a surge of public spiritedness, as locals embraced public saunas, pop-up lunchtime discos, communal contemplation and buying hitherto forbidden rounds of drinks in the bar

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Dinner time at Ateljé Finn, one of Helsinki’s most fashionable restaurants. I was with representatives of the city, Maarit Kivistö and Pekka Timonen. While they tucked into a delicious (they said) slice of horse (I ate reindeer), I mentioned how much I was looking forward to a proper sauna. Not a spell in the charmless wooden cupboards provided elsewhere in the world, but a real Finnish sauna – at once mystical and a source of national pride.

Traditionally, in Finland, people were born in a sauna, and taken there after death to be cleaned: it was the cleanest room in the house or village, and it had hot water. Public saunas account for Finland’s extraordinarily egalitarian ethos: when you are naked in the sauna, nobody is better than anybody else. ‘You can be a general or a top businessman,’ Timonen explained, ‘and it makes no difference.’

Top, the city’s Olympic stadium, and its landmark 72m-high tower, were designed by Yrjö Lindegren and Toivo Jäntti for the 1952 Summer Olympics. K2S Architects created a new wooden canopy for the stadium in 2005; it is now due to be extended over the entire spectator stands. Bottom, the Kamppi Chapel of Silence is a small wooden structure built by K2S Architects off Simonkatu avenue to introduce a place for silence and peace in the lively commercial centre of Helsinki

The great Finnish architect and designer Alvar Aalto proposed a ‘Cultural Sauna’ as a national monument in 1925, and the 1930s were a golden age, with 100 public saunas in Helsinki. But, alas, increasing prosperity saw Finns retreat into their homes to build private facilities, and the number of public saunas dropped to just two.

There remained, it’s true, traditional saunas run by the Finnish Sauna Society, in wooden huts in a pine forest some 20 minutes outside the city by bus. But these are not public saunas: they’re an experiment in elitism that seems frankly un-Finnish. Was the communal approach finished?

No, because suddenly public saunas have become (forgive me) hot again. In the autumn, Finns will be able to try the first new one to open in 50 years. A married couple, architect Tuomas Toivonen and designer Nene Tsuboi of NOW are building exactly what Aalto proposed all those years ago: a Kultuurisauna, a cultural centre, events space and sauna all in one. (On my visit, in early spring, I met Toivonen and Tsuboi at the formal ground-breaking event. It was very cold, and the sea beside us was covered in ice as far as you could see.)

Alvar Aalto’s studio was once located in his 1936 house in the Munkkiniemi district. At one point, more than 20 architects worked here; they moved to a bigger, nearby studio in 1955. The artwork (right, on ledge) is by Aalto himself

The return to public saunas is driven partly by energy policy. There are estimated to be three million saunas in a nation of just 5.4m people, and it takes a lot of power to heat up all those private spaces for three hours, usually with a massive energy surge on Saturday nights, just so their owners can sweat for 15 minutes.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

To accommodate the energy spikes, dirty auxiliary plants need to be fired up at some cost to the environment, but also in cash terms. Providing households with smart metres may help encourage people to embrace a cheaper, cleaner solution. But more needs to be done, because Helsinki, which celebrates its 200th year as Finland’s capital, is growing fast. Planners expect to see the population rise from 1.2m people today to 1.6m in just five years. Toivonen and Tsuboi’s new shared sauna, powered by woodchips, is just one initiative to minimise the impact of such growth. But public saunas aren’t only about saving energy, as everybody kept telling me. They bring people together. And for that reason, to make sure that my first experience would be a convivial one, Kivistö and Timonen decided to find somebody to accompany me.

Made of 600 steel pipes, this monument is dedicated to local composer Jean Sibelius (1865-1957). Designed in 1967 by Eila Hiltunen, it sits in Töölö’s Sibelius Park

The following morning, at breakfast in my hotel, I picked up my cup and studied it carefully. It was blue, almost turquoise. It widened slightly towards the top, enabling waiters to stack it with others of the same kind. It was not huge, but I liked that – and the handle was not too small either. It wasn’t dainty. Although fine, the ceramic felt dense, and sturdy. In short, it was simple, robust and looked great. A design classic, as the words on the base confirmed: it was a ‘Teema’, from the fine company of Iittala. I placed it on a sheet of paper listing my busy itinerary, and took a photograph. If I had a moment to spare, I would buy a cup exactly like it – bring one home with me, as a souvenir from Helsinki, the World Design Capital for 2012. In Finland, the design tradition has very much been about the elaboration of modest, practical goods for the population at large, like this cup, rather than elaborate one-offs for aristocrats. But Kivistö and Timonen went to great lengths to describe how the year of design is about much more than products. It’s being used to improve the quality of life and to nudge Finns towards ‘better’ behaviour. In their attempt to get me to understand this, they had me prowling the guano-encrusted upper precincts of an abandoned abattoir, drinking champagne with teenage fashion bloggers, losing myself in silence at a church that was not a church, discussing with the city’s leading architects the pressing need for more tower blocks, drinking fermented cabbage juice at an upmarket food retailer that sells only Finnish foodstuffs, and alcohol, late into the night, with a group of specialist beer and wine suppliers from overseas.

But design is also about product, and not only manufactured product. When Kivistö turned up to meet me one day, wearing a dark coat that she had customised by painstakingly embroidering a traditional floral design on it, she can hardly have known that home-made clothes are an obsession of mine, and that I would blog about her handiwork at once, using my prehistoric Nokia phone. Nor did she seem to understand why I was so fascinated by the Nokia smartphone she carried around – of a type I could not remember ever seeing people use in the UK. But later in the week she seized the chance to combine my interest in fashion and smartphones by taking me to a catwalk show for the country’s leading label, Ivana Helsinki, and shoving me towards one of the other guests there, Nokia’s design director, Marko Ahtisaari.

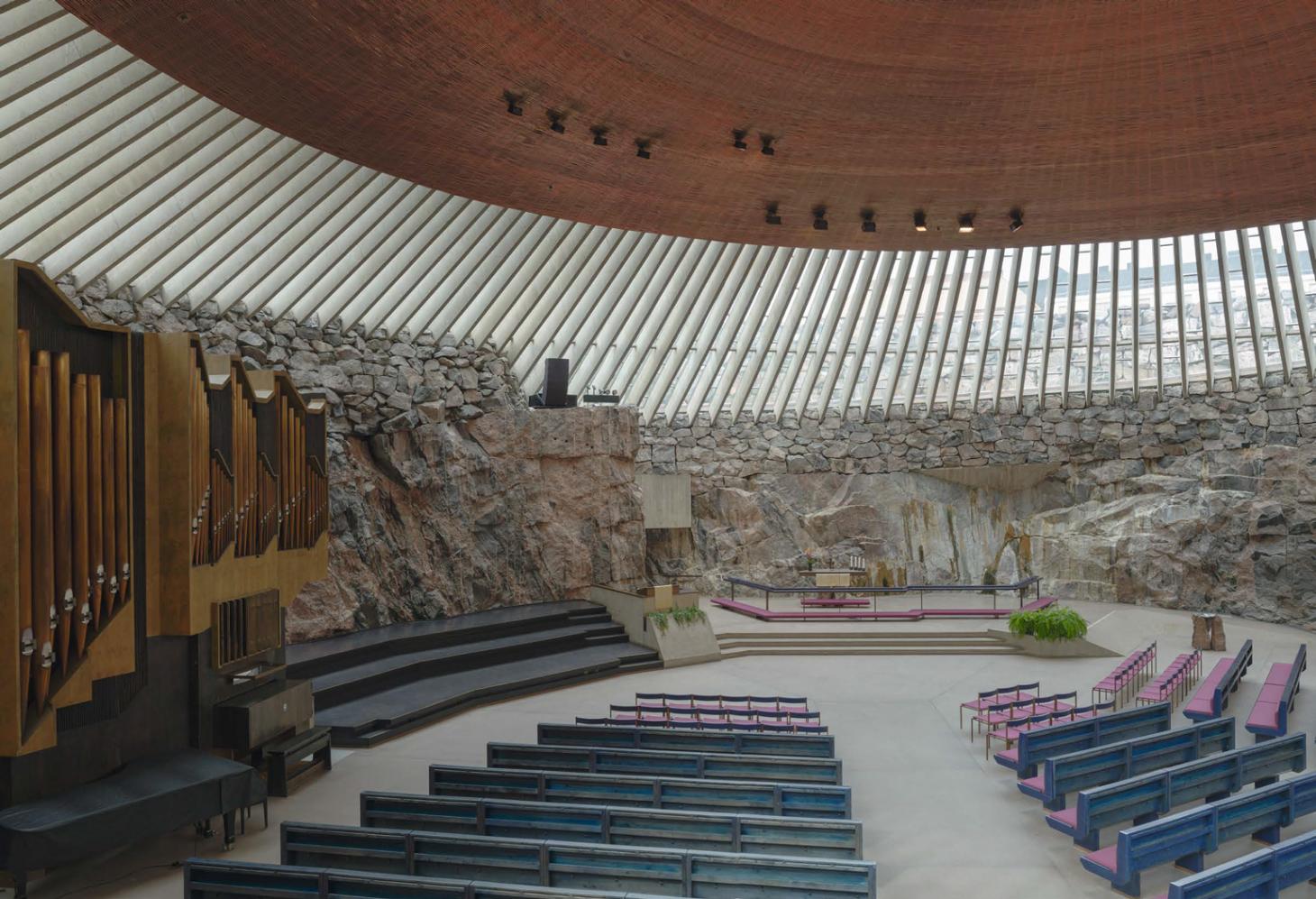

Helsinki’s famed Temppeliaukio Church, by architect brothers Timo and Tuomo Suomalainen, opened in 1969. Built into the rock in the city’s Töölö neighbourhood, it has excellent acoustics and is often used for concerts

For years now, people outside Finland have tended to associate the country largely with one thing: Nokia. But recently Nokia has faltered. The day before I met Ahtisaari – whose father is the Nobel-winning former president of Finland – he’d made a speech declaring that Nokia was about to unleash something revolutionary. Finns were particularly struck by the word vallankumouksellinen (revolutionary) because it seemed rather a grand claim by Finnish standards. In person, Ahtisaari was amiable, not messianic. Nor would he elaborate, but days later Nokia launched its new handset, the Lumia 900, with huge fanfare. In the weeks that followed the phone was found to have problems. And not long afterwards Nokia lost (to Samsung) its 14-year record as manufacturer of more handsets than anybody else.

Another loss to Korea were the shipyards. Finland has a good reputation for shipbuilding – ice-breakers are a speciality – but a Korean company bought Helsinki’s shipyards some time ago, and observers think it’s only a matter of time before the work, too, is taken overseas. All the same, heavy industry and hi-tech still flourish: Kone, the world’s greatest escalator manufacturer, is Finnish; as is Rovio, creator of the massively successful Angry Birds game. But the question for Finland is how to remain ahead.

One possible answer is to be found on the corner of a busy shopping street, beside an upmarket art gallery. The building used to house a piano shop. Today, it represents an experiment in bringing the great ideas to the population at large. Helsinki University leased the building and fitted it out with cheap furniture and encouraging slogans (one wall reads: ‘Hel-thinki’). The idea is to get ordinary people inside to hear academics talk about their work. Hardly a money spinner, but the cost has been reduced by subletting space to a bookshop and a coffee seller; and anyway, the point is to make it easy for taxpayers who fund the university to see the fruit of their investment. When I visited, there was a talk about growing food on green roofs – something the university is helping to install at the new Kultuurisauna.

For Finns who don’t want to fill their minds here, another new space recently became available to empty them. The Chapel of Silence, in the busiest part of town, serves as a meeting place and a spot for quiet reflection. The institution reaching out here is the Lutheran church, which commissioned Kimmo Lintula of K2S Architects to build the chapel as a haven rather than a church – though church employees, and social services, are there if anyone needs them. The curved shape stands out amid the sharp corners of nearby shops. But the most remarkable thing is that the chapel is made of wood – spruce on the outside, black alder inside. Finland has vast forests, and an abundance of timber, but until recently it was difficult to build large structures in wood, because it was deemed to be a fire hazard.

The lobby of Aalto’s 1961 Stora Enso HQ

No such regulations apply in neighbouring Sweden, designers complained. ‘One country says wood burns, the other says it’s OK,’ says Marco Steinberg, of the national innovation body, Sitra. ‘That’s a cultural rather than a technical point. So when we talk about creating change, we’re often talking about cultural change rather than technical innovation.’ Sitra is renovating a whole city block, to reduce environmental impact to the lowest possible: like the chapel, the Low2No block will shun concrete, as much as possible, in favour of wood – now that the law allows it.

For years, Finland has been burdened with extraordinary regulations. Believe it or not, it was, until recently, forbidden to buy a round of drinks in a bar or carry your drink to another table. (The country has a strong tradition of getting smashed together, but also a hardcore temperance movement.) Now, young Finns are pulling down those regulations, or ignoring them.

Tio Tikka in his new restaurant, Suola

Last year, Tio Tikka bought a truck and spent €30,000 renovating it, so he could take to the streets selling coffee and crêpes. But the city authorities refused him a permit. This prompted a massive upswell of popular support for Tikka, including a Facebook campaign. That campaign, in turn, helped to inspire Restaurant Day, in which households all over the country opened their doors to neighbours to cook for them – a mass breach of regulations the government was powerless to stop. One of the founders, Kirsti Tuominen, told me: ‘Finland is a very bureaucratic country. Although we should be proud of the welfare state we have, people have come to expect the government to do everything. Restaurant Day has proved that people are willing to act together to change things for the better.’

Restaurant Day has since been repeated several times, taken up in several other countries, and led to spin-off events. Tuominen invited me to one, a pop-up lunchtime disco. The idea is simple: register beforehand to find out the location, then dance for an hour or so with strangers and friends alike before taking away a prepared lunch box to eat at your desk.

Rather than crack down on these popular events which may break regulations, the authorities seem to be asking, how can we find more? One person helping in that search is Antto Melasniemi. Once keyboard player in Finland’s most successful rock band, His Infernal Majesty, Melasniemi gave up rock and roll to turn himself into a kind of celebrity chef, with his own restaurants and bars. (Including Ateljé Finn, where I watched Kivistö and Timonen eat horse.)

Designed in 1998 by Steven Holl, the curved, light-filled Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art is clearly inspired by Aalto’s architecture

If you can imagine for a moment that Noel Gallagher had given up rock and roll to become, essentially, Jamie Oliver – well, that’s Melasniemi. Only he’s taller, bear-like, with a shaven head, an expression that swings between a scowl and a radiant grin, and a gruff voice with which he utters pithy observations in idiomatic English, perfected during a spell as a chef in London. (One of his favourite expressions is ‘supercool’ – a term he applies generously to much that his eyes fall on.)

Melasniemi is helping the city to overhaul a derelict abattoir. Opening in the autumn, this will involve farmers’ markets and pop-up restaurants – both things Melasniemi knows well. He’s known for his local food ethic, including much foraged material, and events where he uses mirrors to focus sunlight on cooking pots. (If the sun doesn’t shine, the food isn’t cooked. So relax! Have a drink!)

One afternoon I clambered around the upper level of the abattoir with him. He looked over a rusting gantry and gestured towards the icy, cavernous space below, where amateur, Restaurant Day pop-ups might one day, with guidance, become something more lasting. ‘What we are offering here is a training school.’

By working with the government, Melasniemi had become, in effect, the kind of embedded designer that Steinberg told me about. In his previous life, as a teacher at Harvard, Steinberg became interested in why great ideas didn’t happen. ‘Was the architect not good enough? Or was the client not enlightened. I decided that we need to grow more enlightened clients.’ Government support for the World Design Capital made it possible for Steinberg and his allies to widen the discussion, and talk about making design a part of every organisation. He set up a scheme, Inside Job, to embed designers inside every company and public sector body – at board level, like economists. ‘It’s not about bringing design to government. It’s about growing it from the inside. I think of it as a kind of virus.’

A lot of the food initiatives are about rebuilding community, getting people to sit down and break bread together. In part, this is about embracing diversity. The population has changed from six per cent non-Finns to seven per cent – in just a year. ‘Food is a great way to get people to know each other,’ says Melasniemi.

A good example of this is the event he put on where guests were offered free food if they contributed an old plate and a story about it: ‘This old plate was a wedding gift in 1976,’ said one. ‘Since then, it has been in daily use. We have enjoyed morning cereal for years off this tableware. These dishes and my happy marriage have lasted all these years.’

Top, The Arabia Center, home to the Iittala Arabia factory, shop, showroom, and museum. Bottom, artist Kim Simonsson in his Arabia Center studio

I was reminded of that Iittala cup at my hotel, which I’d found eventually at the Arabia factory where they are made. And while I was there I discovered another, time-honoured example of designers being embedded within a company. By long-standing arrangement, the enlightened manufacturer has provided space on its top floor for ceramicists to make their own art, with a back door elevator connecting them directly to the factory, and free use of materials and kiln. I met one of the younger designers, Heini Riitahuhta, and also looked around the messy studio of Kim Simonsson, whose gothic ceramic figures came to the world’s attention when Charles Saatchi started buying them. (Simonsson’s work, especially, taps into the mystical, melancholic yet humorous Finnish tradition, perhaps more often associated with Slavs.) But what seemed so particularly civilised about the embedding of these artists was that the company makes no specific demands of them: there’s no requirement that they produce anything whatever for mass production. But they usually do, anyway. ‘Both sides benefit,’ confirmed Riitahuhta, working when I met her on a floral design for tableware.

At the beautiful 1920s Yrjönkatu public baths, I strode into the changing cubicle provided, noted that a bed had been supplied (you should never hurry a sauna), and took off all my clothes before striding out again. Catching up with Melasniemi, I followed him into the shower area, and pretended not to be surprised to find a woman offering massage to men going in and out of the sauna. Then I walked boldly inside the dark steam room and headed for the top bench. Melasniemi sat on my right. To my left, a couple of older men were speaking in low voices.

I tried to taste the lölyly. The word means something like steam, but it has deeper meaning too. ‘It also means something more like, “ancestors”,’ Timonen told me. The best sauna is the one with the best lölyly: a balance of humidity, how long it lasts, and how it embraces you. The lölyly at Yrjönkatu seemed good to me: not too dry, not too humid. But hot. After a short while, Melasniemi left the room. I knew I should not regard the sauna as a competition, but felt pleased to have lasted as long as him.

Local architect Reijo Jallinoja’s Terassitalo apartment block, built in 1994, is typical of the architecture of Helsinki’s Pikku Huopalahti. Built in the 1980s and 1990s, the district is known for its ‘Legoland’ effect, with many of its buildings featuring geometric elements and bright colours

A couple of young men came in. Politely, they consulted the older men before adding more water. Then more older men came in. They might have been top businessmen, or generals – but obviously I couldn’t tell. Then a young man whose toned musculature suggested gym membership. Then a fat man. Then the first pair of older men departed – and I followed soon after, rejoining Melasniemi on the balcony overlooking the pool. I was glad to see him, a near-stranger who, after our sauna together, felt like an old friend. We’d been cold earlier. Now our skin was pink and our bodies warm.

In the next couple of days, he would generously take me to his other restaurants, and to the city’s only other public sauna – the shabbier but similarly atmospheric Kotiharjun, in a working class district. There, between late-evening bouts of steam, we retreated to sit on a wall on the residential street outside – a line of pink, all-but naked men who would have looked extremely odd in London, but were taken for granted in Helsinki. But that was still to come.

At Yrjönkatu, a waitress (fully clothed) approached us in our nakedness and took an order from Melasniemi. (Once again, I tried to look like this was no big deal.) Melasniemi ordered beers, a dish of herring on rye and a side order of pickled cucumbers with sour cream and honey to dip them in. Casually, he mentioned he had been called in to help design the menu here. It dawned on me, with some relief, that his generous offer to show me round Helsinki had not been entirely without self-interest.

Then the food came. It was delicious.