Q&A: Anne Hardy

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

W*: People usually think of photography as an instantaneous snapshot of a moment in time, but your images seem to convey a lot of history. How do you achieve this?

AH: When I create a photograph it is made over a long period of time and the final image captures this history and all that is contained in it. It sort of steeps like tea - I view the work through the camera lens while making it and the photograph reflects that.

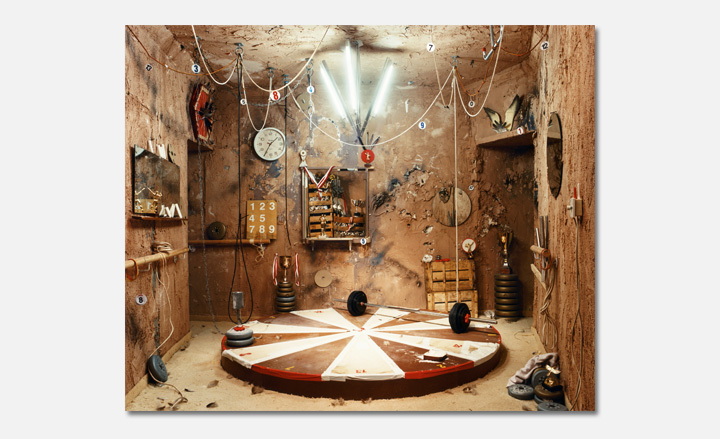

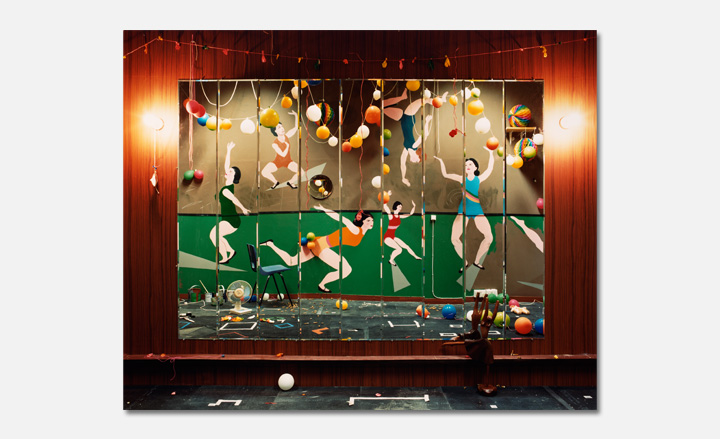

There is an almost post-apocalyptic quality to the work of British artist Anne Hardy. In shot after shot, the sense of abandonment – rooms utterly bleached of life, a grungy workout space, hallways stuffed with the detritus of a panicked leave-taking – comes through. It’s as if she’s chanced on an entire city that’s been sacked and pillaged, and she’s decided to meticulously document every corner.

The surprise, of course, is that every claustrophobic scene is, in reality, a set that has been painstakingly constructed over several months, but there is never any hint of artifice. Hardy – who first trained in painting at The Cheltenham School of Fine Art before landing in the Royal College of Arts where she studied photography – shoots with a medium-format camera and wide-angled lens.

In her work, she captures portraits of decay, loss, pain and a wistfulness for what has passed. The lasting impression may be a record of the end of civilization, but in Hardy’s images, you get the unnerving feeling that just out of range of the photograph, someone is still here, still present in the room and silently watching. Her most impressive achievement lies in the slowly dawning realisation that that someone is you.

Hardy recently had a solo exhibition at the Vienna Secession, and was a panelist on 'Truth or Lies? Aesthetic and Documentary Strategies in Contemporary Culture' at Le Méridien, Vienna. The discussion took place on 18 September and was organised by Le Méridien Hotels & Resorts and Outset Contemporary Art Fund as part of the Outset Le Méridien Talk Series.

Wallpaper*: The scenes you create look like they have been lived-in and the contents evolved over a long time. Do you know exactly what the image will look like before you start?

Anne Hardy: I bring a place into being, imaginatively and physically by using the suggestive qualities of the various materials and objects that I work with. When I begin a new piece of work I set myself parameters to work within and the place and image that I make emerge out of a process of experimenting and testing of materials. There is a tussle between myself and the 'stuff' that I work with, and the camera creates an arena for this to happen in.

W*: There are no people in your images, although the scenes often depict a lived-in feel. Can you explain why you don't show the people but just hint at their existence?

AH: The images are about space, and your encounter with a space, and its presence via the image and your imagination. It's not necessary to include people.

W*: Many of your photographs have a painted quality; can you explain how you manipulate your images to give this effect?

AH: If your question is to do with Photoshop or digital manipulation of the images, there is none. I work with conventional photographic negative and printing and the analogue approach and lack of post-production is important to me. I am interested in the fragility of the image and of the illusion, both literally (the structures are themselves fragile) and conceptually, so it's important to me that everything that appears in the image actually happens in front of the camera.

W*: The subjects of your photographs take a lot of constructing; do you see yourself as a photographer first, or as a sculptor?

AH: I am probably a sculptor who creates something that in the end is photographic and is also informed by painting, which is what I studied first.

W*: Your work is only ever shown as a photograph, and not an installation. What is the reason for this?

AH: Until now that has been the case. I am interested in how we relate to the world around us via our imagination. We think that we know many things about the world we are part of but very few of these come via our own direct experience and so I have been interested to find a photographic equivalent to a literary space, one that allows an encounter and exploration of space that has a relationship to what we think of as real or potentially real but at the same time is a fiction.

W*: A lot of the images you create have a dreamlike quality, where does your inspiration come from?

AH: Particular architectural forms or objects have all formed starting points for pieces of work, as have ordering and classification systems. The structures I build reference informal forms of architecture, in particular the accumulative and adaptive architecture found in a densely-built city.

Literature is also an important reference and the artist book accompanying my exhibition at the Secession contains excerpts from novels by Haruki Murakami, Stanisław Lem, Raymond Carver, Bret Easton Ellis and Tom McCarthy, and the first chapter from JG Ballard's novel Concrete Island. This describes the moment when the protagonist leaves his normal world and enters a parallel one - he becomes invisible. This is the kind of space I am fascinated with in my work. It is just there, next to you, and you don't see it. It is, perhaps, the kind of space you might imagine exists.

See Anne Hardy's solo exhibiton at the Vienna Secession here

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

'Cipher', 2007. Image courtesy Maureen Paley, London

'Rehearsal', 2010. Image courtesy Maureen Paley, London

'Rift', 2011. Image courtesy Maureen Paley, London

'Suite', 2012. Image courtesy Maureen Paley, London