Four innovative design responses to the climate emergency

Design Emergency began as an Instagram Live series during the Covid-19 pandemic and is now becoming a wake-up call to the world, and compelling evidence of the power of design to effect radical and far-reaching change. Co-founders Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn took over the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper* –

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Tragic and destructive though the Covid-19 crisis has been, it is one of a tsunami of threats to assail us at the same time. A concise list of current calamities includes the global refugee crisis; spiralling inequality, injustice and poverty; terrifying terrorist attacks and killing sprees; seemingly unstoppable conflicts; and, of course, the climate emergency. Since the start of the pandemic, global outrage against systemic racism following the tragic killing of George Floyd, and the destruction of much of Beirut have joined the list. Design is not a panacea to any of these problems, but it is a powerful tool to help us to tackle them, which is why Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn are focusing Design Emergency on the most promising global efforts to redesign and reconstruct our lives for the future.

Thankfully, there are plenty of resourceful, ingenious, inspiring and empathetic design projects to give grounds for optimism. Take the climate emergency, where design innovations on all fronts: from the generation of clean, renewable energy, to new forms of sustainable food growing, and rewilding programmes are already making a significant difference to the quality of the environment.

Here are four of Paola Antonelli and Alice Rawsthorn’s favourite design responses to the ecological crisis.

The Ocean Cleanup

Scientists claimed that it wouldn’t work. Environmentalists warned that it risked damaging marine life. Few design projects of recent years have been as fiercely criticised as the Ocean Cleanup, the Dutch social enterprise founded in 2013 by Boyan Slat, who quit his degree in design engineering to try to tackle one of the biggest pollution problems of our time by clearing the plastic trash that is poisoning our oceans. Despite its critics and a series of setbacks, notably when the original rig had to be towed back to San Francisco to resolve technical problems, the Ocean Cleanup has persevered. The redesigned System 001/B (pictured top) successfully completed its trials in the Pacific last year, and System 002 is scheduled for launch next year. The Ocean Cleanup has also developed a parallel project, The Interceptor, a solar-powered catamaran with a trash-collecting system designed specifically for rivers, and which can extract 50,000kg of plastic per day.

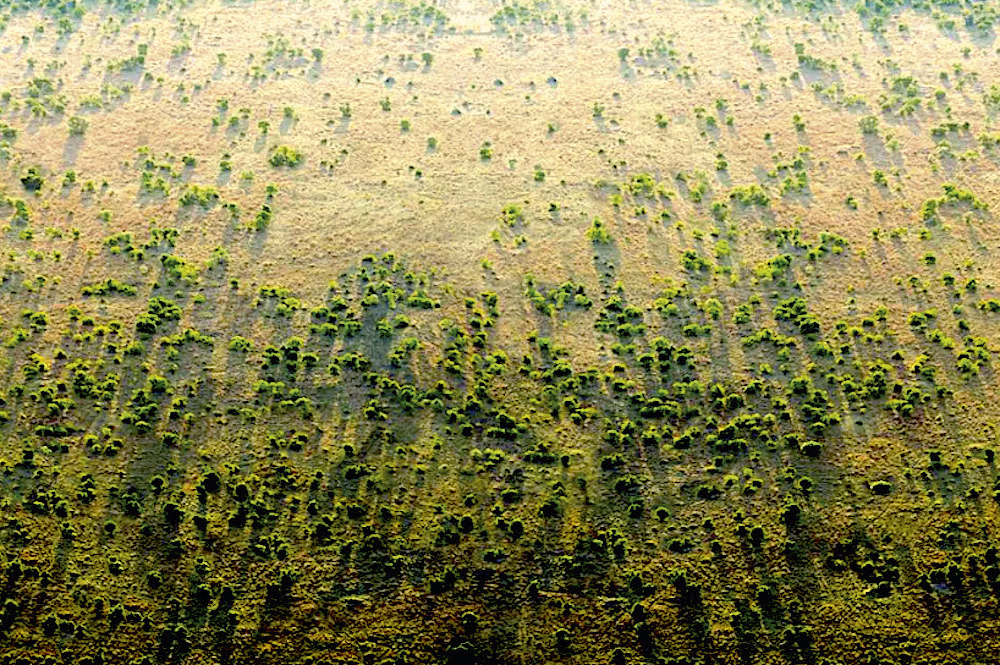

The Great Green Wall

Few regions are hotter, drier and poorer than the Sahel, on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert. The brutal climate has wrought devastating damage in recent decades by causing droughts, famine, conflicts, poverty and mass migration. The Great Green Wall is an epically ambitious project launched in 2007 by the 21 countries in the Sahel to restore the land by planting an 8,000km strip of trees and plants from the Atlantic coast of Senegal to Djibouti on the Red Sea. The practical work on the Great Green Wall, which is run as an African-led collective supported by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, is executed by each of the 21 countries. So far, more than 1,200km of greenery has been planted, although the focus of the project is less on the progress of the wall itself, than on its impact in persuading each country in the Sahel region to transform what has become arid desert back into fertile farmland.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

available to download free here – to present stories of design’s new purpose and promise.

Zero-waste village

This was to have been the year when the people of Kamikatsu, a village on the Japanese island of Shikoku, would achieve their goal of becoming a zero-waste community. The 1,500 villagers may struggle to produce no waste at all in 2020 but will come impressively close to doing so in a 20-year experiment that demonstrates the contribution a resourceful group of individuals can make to curb the climate emergency. The initiative began in 2000, when the local government ordered the closure of Kamikatsu’s incinerator. Rather than ship their waste elsewhere, the villagers took a collective decision to reduce and, eventually, eliminate it. They opened a Zero Waste Academy, where waste is sorted into 45 categories for reuse or recycling. Anything sellable is dispatched to a recycling store; fabric is upcycled at the craft centre. The villagers have now eliminated over 80 per cent of their waste, but are still struggling to recycle leather shoes, nappies and a few other tricky exceptions.

Urban farm

Looming beside the Porte de Versailles subway station in south-west Paris is the colossal exhibition venue Paris Expo Porte de Versailles. By the time it hosts the handball and table tennis events in the Paris 2024 Olympics, Paris Expo will also be the home of Agripolis, the largest urban farm in Europe. Agripolis already operates other urban farms in Paris and occupies 4,000 sq m of Paris Expo’s roof. Over the next two years, it plans to expand across another 10,000 sq m, to produce up to 1,000kg of fresh fruit and vegetables each day using organic methods and a team of 20 farmers. The produce will be sold to shops, cafés and hotels in the local area, while local residents will also be able to rent wooden crates on the roof to grow their own fruit and vegetables. Once it is completed, Agripolis’ gigantic rooftop farm at Paris Expo should place the Ville de Paris’ programme of encouraging urban agriculture at the forefront of global developments in greening our cities.

INFORMATION

A version of this story appeared in the October 2020 issue of Wallpaper*, guest edited by Design Emergency. A free PDF download of the issue is available here.

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.