‘Azzedine Alaïa: The Couturier’ celebrates the designer’s extraordinary cut and dash with the help of a few friends

Azzedine Alaïa dedicated his life to designing clothes that transcended trends, super-enhanced the female physique and upheld the classical ideal. His designs had an apparent simplicity, hard-won through fearless experimentation and technical complexity. One of the last projects he worked on before he passed away in November 2017 was a solo show at London’s Design Museum that would tie in with a new Maison Alaïa flagship store on Bond Street.

Alaïa had prepared the exhibition with gallerist Carla Sozzani, curator Mark Wilson, and the co-director of the Design Museum Alice Black. Entitled ‘Azzedine Alaïa: The Couturier’, it will showcase more than 60 outstanding pieces in front of a series of five monumental screens. ‘There has never been an Alaïa show in London. He did not stage big fashion shows and while he was an icon, he was also quite private,’ says Sozzani, founder of Galleria Carla Sozzani and 10 Corso Como in Milan. ‘People don’t necessarily know about his work so it’s wonderful to have this show – the first fashion exhibition at the Design Museum’s Kensington location.’

‘We saw the show as an installation rather than a retrospective,’ says Wilson, who had masterminded two Alaïa shows in 1997 and 2011 at the Netherlands’ Groninger Museum, where he works as chief curator. He came up with the idea for the screens to highlight the sculptural qualities of Alaïa’s clothes: ‘The architectural interventions allow for a 360-degree take on every piece. And it was obvious as to who would make them, as Alaïa had such great relationships with those designers and collected their work.’

Marc Newson, Konstantin Grcic, Kris Ruhs and the Bouroullec brothers were invited to collaborate. To all, Alaïa was a friend, patron and mentor. The brief was to create screens that would complement Alaïa’s work. All battled with the structural complexities of making vast freestanding pieces that could be assembled on site.

In terms of scale, Newson’s is the most ambitious. ‘It was crucial that the pieces remain about Alaïa rather than those intervening to enhance his work,’ says Newson. ‘That’s what we do as designers. I am always working for clients before working for myself. This project was no different, but there is a personal tinge to it because of our friendship,’ adds Newson, who first met Alaïa, through Sozzani, when living in Paris in the early 1990s.

Alaïa collected numerous Newson pieces, including the first aluminium lounger that he made as part of his graduate collection at art school in Sydney. ‘I’ve no idea of how he got hold of it,’ says Newson.

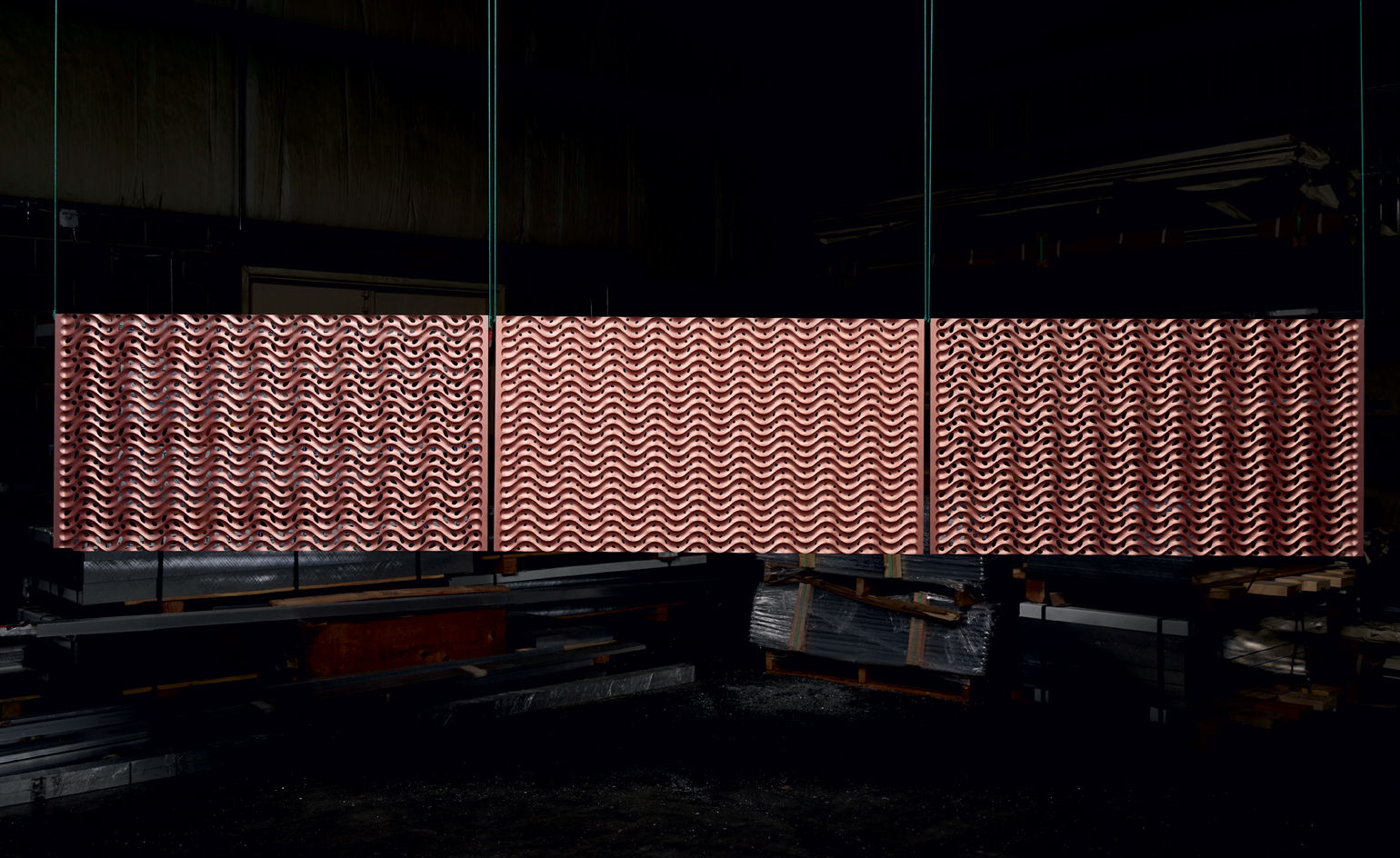

‘There are qualities in Alaïa’s work which shine through: simplicity mixed with technical complexity, rigour, subtlety, sensuality and transparency,’ he continues. ‘There is transparency in many of his garments and that is also the quality of a screen. It’s not a wall, but it has to have some play of light and movement within the absolute structural parameters.’ Newson chose anodised aluminium for his design, adding ‘the metal contrasts and complements the idea that everything around it is a textile’.

The piece, made by aluminium specialist Neal Feay in California, comprises 64 giant tiles, patterned using machine tools and boasting a soft, velvet-like surface. ‘The panels intersect, creating a random yet orderly pattern – almost like a houndstooth,’ says Newson. ‘The anodising process creates these subtle, profound colours – in this case, a flesh pink hue that Alaïa loved. It doesn’t look like hard metal, but sensual and tactile.’

The mission of giving hard surfaces a soft textile-like appearance is a nod to Alaïa’s own material experiments. If he could not find what he liked, he had it developed. He worked in densely-knit tricot for his famous body-sculpting dresses, in fine leather that he made appear as malleable as silk, in semisheer chiffon, sinuous bias-cut silk jersey and laser-cut lace. ‘He would often combine hard architectural elements, such as studs, with fluid materials, creating a tension,’ says Wilson, who has arranged the garments in themes, including volume, African-inspired outfits, black and bandage dresses.

Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec first met Alaïa in 2002 at the opening of their show at Galerie Kreo. Alaïa bought almost the entire collection. ‘It was a sympathetic meeting of shy people with like minds,’ says Ronan. For the Design Museum show, the duo decided on a glass screen. ‘Alaïa had a very precise understanding of silhouette. His clothes are elegant, refined and precise,’ says Ronan. Their textured glass panels (manufactured by Schott AG in Germany) are embedded with a film that creates a wave of gradating grey tones. ‘The quality is neither transparent nor opaque, but translucent,’ says Ronan.

It will be in sharp contrast to the contribution from sculptor Kris Ruhs, who worked with craftsmen in his Marrakech studio for a highly textural, organic piece. ‘It’s like a piece of jewellery, handmade in aluminium,’ says Ruhs. The artist, who created accessories for Alaïa, as well as store interiors, has also worked on a second screen for the show, to display artworks by Alaïa’s partner Christoph von Weyhe.

Konstantin Grcic’s screen is fashioned from polished stainless steel, manufactured by Ronchetti in Italy. ‘Because of the reflective surface, the material becomes somewhat immaterial, like a mirror,’ says Grcic, who constructed the piece from a grid-like pattern of panels. ‘The metal has an undulating surface and one edge is laser cut in a zigzag, like the cut of a tailor’s pinking shears.’ Alaïa owned several Grcic pieces, including a table and a vitrine from his Galerie Kreo shows.

Alaïa’s extensive collection of design and fashion is meticulously archived and housed in the Marais. ‘It’s a subterranean space that has to be as big as a Parisian block,’ says Newson. Works are also on show in his atelier and in stores. The 6,000 sq ft Maison Alaïa store on Bond Street, which is set over three floors, displays designs by Piero Lissoni, Renzo Piano, Naoto Fukasawa, wall sculptures by Ruhs and paintings by von Weyhe, curated by Alaïa and Sozzani, who will now oversee the studio and collections and head up the Azzedine Alaïa Foundation.

Alaïa’s last couture collection was presented in July 2017 and starred his friend Naomi Campbell in a striking velvet bodice and studded pleated gown. Several pieces from this collection will be on show. The giant-scale outfits are juxtaposed with film footage and Richard Wentworth’s almost forensic photographs of the atelier, which he shot over a period of two years. Legions of devotees, including Charlotte Stockdale, Farida Khelfa, Sofia Coppola, Brigitte Macron and Michelle Obama, worship the liberation (the construction is so meticulous that constrictive underwear is unnecessary) and refined eroticism of Alaïa’s clothes. At the time of his death, he was occupied with rescaling all the looks in the show to work with the epic dimensions of the installation.

Just as there is a sense of beautiful complicity between the couturier and the wearer, with Alaïa’s clothes there is also a union of design and culture. ‘All the designers you speak to have such reverence for Alaïa. Through the show we wanted to underline and appreciate that,’ says Black. Adds Newson, ‘Alaïa’s sphere of appreciation was just so broad – he was far more interested in design in general than fashion specifically.’

That like-mindedness was not simply theoretical. It was in Alaïa’s kitchen during his frequent gatherings that bonds were sealed. ‘His circle of friends was vast and from all walks of life. You could be sitting next to Catherine Deneuve, Lauren Bacall, Tadao Ando or Jack Lang – he had a fervid interest in so many things, a big heart and a really mischievous sense of humour,’ reminisces Newson. Says Wilson, ‘The exhibition will be a vision of the epic and the intimate, and a celebration of a generous genius at the epicentre of 20th- and 21st-century design.

Much of Alaïa’s design collection was purchased from Didier and Clémence Krzentowski, founders of Galerie Kreo in Paris. We talk to Clémence about their relationship...

Wallpaper*: How did you first meet Alaïa?

Clémence Krzentowski: Didier and I did a show with Marc [Newson] in 2000, the year after our gallery opened, which is when we met Azzedine. We have a saying in French – ‘On s’est rencontrés et on est tombés amoureux’ – which means we met and fell in love. It was instant connection. Azzedine often referred to Didier as his brother, and Christoph [von Weyhe] said that, in some ways, they even looked alike.

W*: What was your friendship with him like?

CK: We shared all the important moments of our lives with Azzedine. He came to the gallery to see every show, and we often went to events and design fairs together. Most of our encounters were in his kitchen, which was like a second home to us. We talked about fashion and design, but also art, food and nature. He was fascinated by everything. I once asked one of his assistants what he’d learned from Azzedine and he very earnestly replied, ‘I learned life’.

W*: Who did Alaïa admire?

CK: Azzedine loved Marc’s work from the beginning. Marc barely speaks French, and Azzedine didn’t speak English, but they understood each other completely, and Azzedine had a lot of joy in designing the wedding dress for Marc’s wife, Charlotte [Stockdale]. He also had a deep respect and admiration for Konstantin [Grcic], as they were both radical thinkers who enjoyed discovering new things. As for Ronan and Erwan [Bouroullec], he collected their work from the beginning. And since they lived in Paris, they would sometimes come to his kitchen, too.

W*: Do you see similarities in the ways in which Alaïa designed couture and collected furniture?

CK: He was fantastically open-minded about collecting, just as he was about designing. The only criteria he cared about was the content behind each thing. If a piece was interesting, he would want to have it, whether it was a light, a table, a chair, or a work of fashion, art or photography. But he didn’t collect that many names; it would be many pieces from the same people. His relationship with them ran deep.

W*: How was his design collection displayed?

CK: He lived with his pieces, from the Jean Prouvé petrol station that was in his bedroom to pieces by Konstantin and Ronan and Erwan. He had a lot of respect for his things, but he also believed that they should be enjoyed. Since he had too many pieces to have them all at home, the rest was kept at his Paris studio and workshop on rue de la Verrerie. Sometimes we would go and look at all the big boxes containing pieces that hadn’t yet been installed. I do hope they will find their way to his foundation.

As originally featured in the June 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*231)

Related: Jony Ive remembers Azzedine Alaïa

‘Azzedine Alaïa: The Couturier’, features 60 pieces by the renowned couturier, one of the last projects Alaïa worked on before he passed away in November 2017.

Garments in the exhibition have been presented against five monumental screens, designed by Marc Newson, Konstantin Grcic, Kris Ruhs and the Bouroullec brothers.

INFORMATION

‘Azzedine Alaïa: The Couturier’ is on view until 7 October. For more information, visit the Design Museum website

ADDRESS

Design Museum

224-238 Kensinton High Street

Kensington

London

W8 6AG

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.