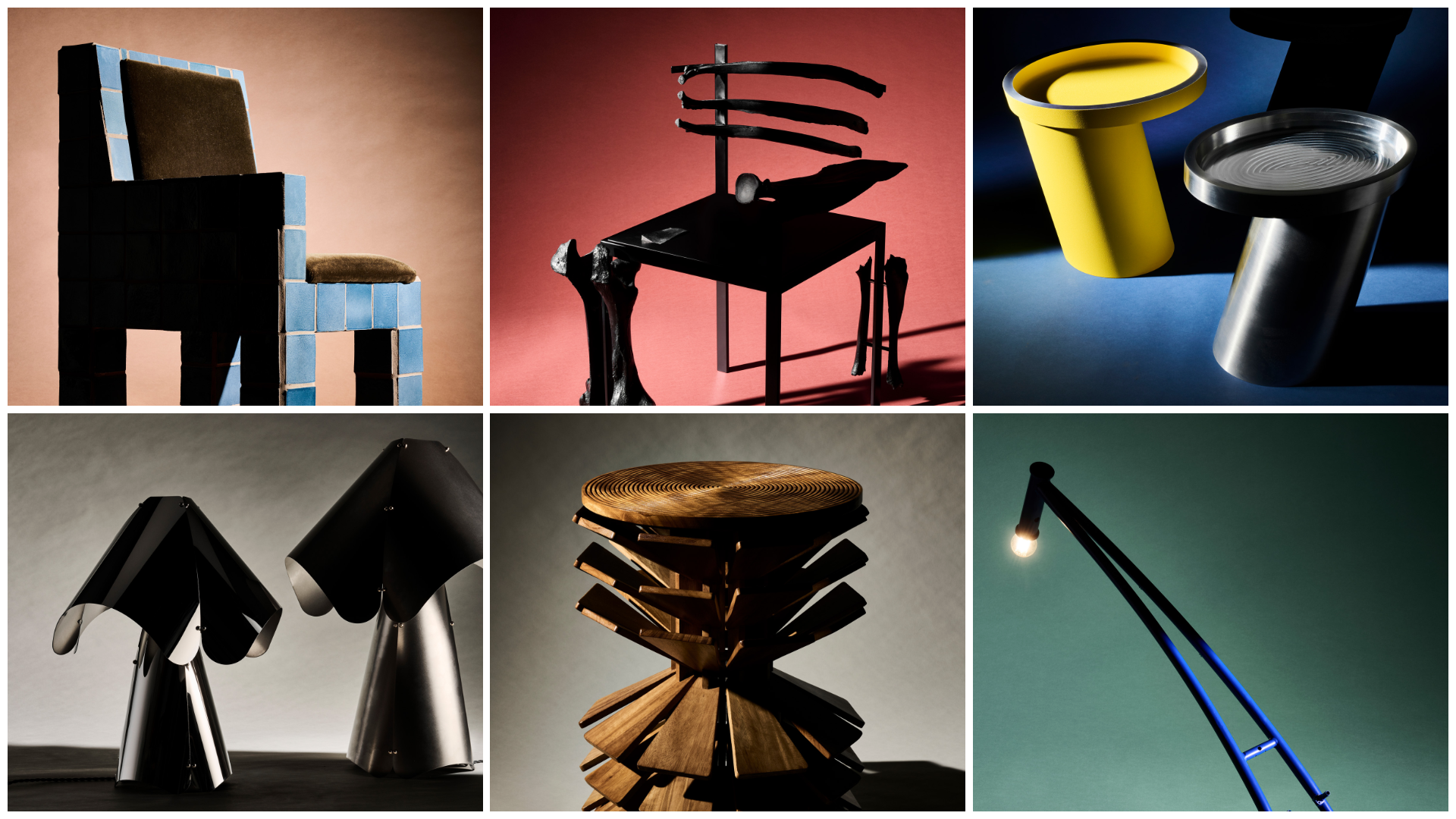

These are the 12 emerging designers we are excited to follow into 2026

These are the designers to watch for 2026: from unpredictable glassmakers to furniture designers working with bones, textile artists exploring ancient techniques and makers giving new life to mundane tools

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every year, Wallpaper* turns its lens to the ascending stars of design, searching the globe for the names that we look forward to seeing emerging and expanding. They are designers, makers and creatives that are bound to shake up the design industry with new ideas, processes, and ways to see everyday objects.

This year's cohort of 12 designers is united by a mission to explore new ways to reflect the language of industrial design, using the materials and technique of the industry in novel ways.

Future Icons: the emerging designers to watch in 2026

Cordon Salon

Australian designer Ella Saddington grew up on a farm, where she learnt from an early age about problem solving. ‘It was not quite the outback, but remote enough that resourcefulness was essential – when something broke, you couldn’t just head to the shops.’ She started Cordon Salon as a way to explore skills and craft from an anthropological context, merging knowledge and theory to create something tangible and meaningful.

Among her most significant projects to date is her ‘Garniture’ collection of lamps (pictured above), the result of exploring Western European plate steel armour from a historical and technical perspective.

Grace Atkinson

Grace Atkinson’s distinctive rugs, blankets and wall hangings are made using centuries-old techniques and rendered in vivid shades of soft wool, silk and mohair. ‘My work oscillates between design and art, so it’s often the setting that contextualises it,’ says the Paris-based designer, who grew up in Lake Wānaka, New Zealand, surrounded by textiles and garments from the vintage shop run by her mother.

Her studio practice formally launched in 2022, and she often works with artisans from other countries, such as Ukraine, Spain and Portugal, with the aim of helping to preserve their craft. Her furry textiles (pictured here), made in collaboration with Ukrainian artisans using an ancient Hutsul technique, are particularly eye-catching. ‘The friendships built make the work far more meaningful, particularly given the adversity my collaborators in Ukraine have faced,’ she adds.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Anda Ba

Born in London, but raised in the Punjab city of Ludhiana, Armaan Bansal was spurred on to become a designer by Wallpaper*. ‘I used to travel between India and London as a child, and the airport lounges had issues lying around,’ he says. ‘It became my window into the global design landscape.’

Working across various mediums including furniture, architecture and fashion, Bansal merges modernity and heritage, drawing inspiration from India’s natural materials and contemporary London culture. Collaboration is a fundamental part of Bansal’s practice. His ‘Fly-Ash’ collection (pictured here), with Indian interiors brand Essentia Home, began with a conversation about creating an Indian identity that felt rooted in history, yet could exist comfortably in a Delhi home or an English countryside house. ‘They had deep confidence in their craft and trusted my vision,’ says Bansal. ‘It felt like a natural fit.’

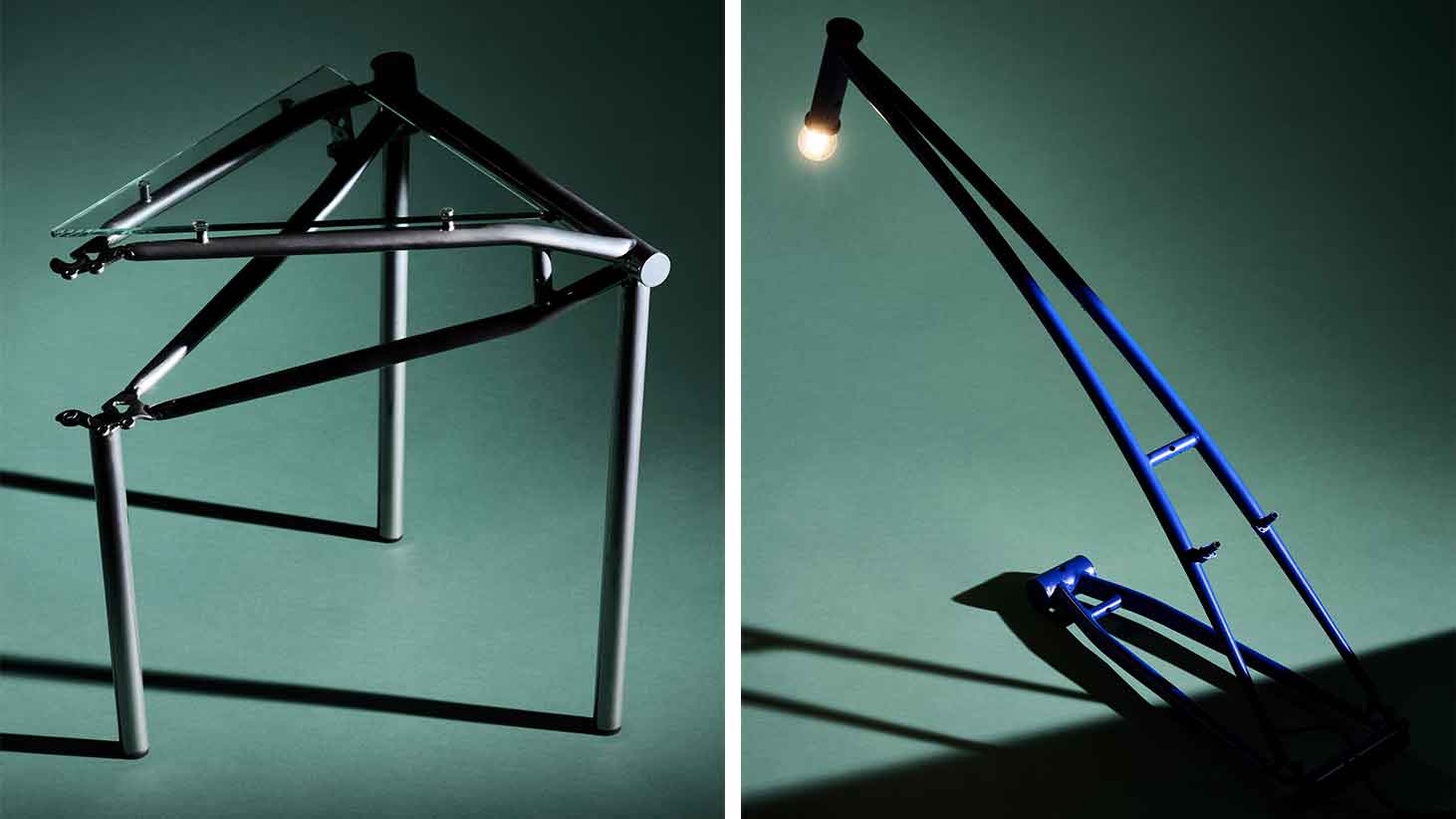

Cara Campos

Born and raised in the Middle East to a French father and an Irish mother, Cara Campos says she spent her formative years ‘swimming in a Long Island iced tea of cultural influences’. She had a peripatetic childhood before eventually returning to Ireland in her early 20s to initially study fashion design before eventually changing course to industrial design, graduating in 2025.

The pieces in her recent ‘Objects from Frames’ collection (pictured here), which began as a university project, are formed from abandoned bicycle parts. ‘Bicycle frames are fascinating because they’re so precisely engineered, yet once they’re no longer functional, they’re often just discarded,’ she says. ‘Using them in my designs felt like a way to give them a new identity.'

Supersedia

Hanging out in his father’s metal workshop in Bressanone, in northern Italy, meant Markus Töll was exposed to tools and materials from a young age, and he credits this time as giving him an understanding of ‘the constant dialogue between an idea and its realisation’. He chose the name Supersedia for his studio as a fusion of Italian words for ‘superlative’ and ‘chair’. ‘I create what I consider to be superlative chairs, sculptural forms that follow emotional thoughts as much as the will of the material itself,’ he says.

The ‘Superdaybed’ (pictured here) is his take on a traditional daybed – it consists of a steel frame supporting a series of upholstered cylinders, offering a contemporary interpretation on a classic archetype.

Palma

Artist Cléo Döbberthin and architect Lorenzo Lo Schiavo co-founded the São Paulo-based Studio Palma in 2020 with a vision to establish a cross-pollinating practice, where art and architecture share a single tactile language. Palma was born with the practice’s output pivoting on paradox: accidental yet intentional, mathematical yet poetic.

Its 2024 ‘Belisco’ floor lamp (pictured here) embodies this balance – its geometric precision softened by sculptural tactility, an object oscillating between art and utility. ‘My experience as a designer combined with Cléo’s artist practice allows us to expand the traditional boundaries of each field into a more experimental approach that continues to permeate Palma’s output,’ says Lo Schiavo.

Eddie Olin

In the five years since launching, Eddie Olin’s practice has become synonymous with pieces that balance heavy metal with a sense of playfulness and visual lightness. His work celebrates the oft-overlooked aesthetic value of engineering processes and techniques, using them to create furniture with precise, clean forms that hint at his background in typography.

His CNC-machined aluminium ‘Snoopy’ table (pictured here) stemmed from a simple observation. ‘I was making a day bed that had a large hole cut through to be connected with an angled tube,’ he recalls. ‘Before the tube got welded inside, it was sitting around and I found the visual quite enjoyable. ‘The name is a nod to the Castiglioni lamp, which also uses a similar counterbalanced visual.’

Silje Lindrup

In Nr Lyngby in northern Denmark, Silje Lindrup shapes molten glass into sculptural forms that seem to hover between control and chaos. Lindrup grew up not far away, in Lønstrup, which is home to a large craft community. As a teen, she worked for a neighbour, who was a glassblower, an early experience that shaped a lifelong connection to handmade processes and the unpredictable behaviour of hot glass. ‘I have to be in the material to know what I’m capable of,’ she says.

Her ‘Melt’ series (pictured here), in which she heated up glass to extreme temperatures, embodies this dialogue between form and freedom. The pieces appear frozen mid-motion, a record of glass in flux. ‘I’ve been trained to be the one in control when working with glass,’ she says. ‘Here the hot glass decides when to stop moving.’

Salù Iwadi Studio

Based between Lagos and Dakar, Toluwalase Rufai and Sandia Nassila explore the relationship between materiality, craftsmanship and cultural memory through collaboration with artisans across the African continent. They set up Salù Iwadi Studio as ‘a practice grounded in cultural depth and material inquiry, aiming to reclaim and reinterpret African narratives through material and form, offering them renewed presence in the global design conversation’.

Their ‘Zangbeto’ side table (pictured above) was inspired by Benin’s masquerades, and its form conceals themes of presence and protection. ‘These works trace our search for a new design language,’ they say. ‘One that honours the past, reclaims local materials, and imagines new futures for African design.’

Ah Um Design Studio

Zack Nestel-Patt’s path into furniture design has been somewhat circuitous. ‘For the first 35 years of my life, I studied jazz and classical bass, pursuing that as a career,’ says the founder of Ah Um Design Studio. ‘It wasn’t until I moved to LA and got a part-time job sanding cremation urns that I started woodworking. Then I made some pieces for my home, some folks saw them and suggested I take them to a market. The reception was so humbling, it forced me to take it seriously.’

At NYC x Design 2024, he launched his 11-piece ‘Jura’ collection (pictured here), featuring chairs, tables, lamps and mirrors defined by zigzagging wooden frames, mohair and bouclé upholstery, and distinctive tiles.

Zbeul Studio

‘Material is our way of thinking,’ says Thomas Noui. Together with Victor Robin, he founded Zbeul Studio in 2023, based in Paris and ‘born out of a shared desire to create a design studio that combines historical research with technical approaches.’ ‘Zbeul’ derives from an Arabic root word referring to rubbish. ‘In French slang, this term has been adapted to mean mess or chaos,’ explains Noui. ‘We found it interesting to adopt this unflattering term in reference to our appetite for seeking out unconventional materials.’

A notable project is their ‘Archeologia’ chair (pictured here), which is crafted from animal bone. The duo adapted traditional wood-staining techniques to achieve a deep black finish that accentuates the microscopic detail of the surface. The result is an object that feels both primal and experimental. ‘The challenge was to play with the boundaries between beauty and repulsion.’

Yoonjeong Lee

The work of Korean designer Yoonjeong Lee focuses on contemplating the mundane to reveal and elevate hidden details that are not often obvious to the viewer. ‘Rather than seeking specific inspiration, my work centres on the ordinary,’ she says. ‘This includes objects that are small, quiet or disappearing, elements that are overlooked or forgotten.’

Nails are a recurring theme in her work, either existing as objects on their own or shown in frames and cases as jewellery objects (‘I find great delight in the process of creating independent value for these subjects,’ she says), cast as organic elements with irregular edges, keeping their function intact but expanding on their aesthetic potential.

Rosa Bertoli was born in Udine, Italy, and now lives in London. Since 2014, she has been the Design Editor of Wallpaper*, where she oversees design content for the print and online editions, as well as special editorial projects. Through her role at Wallpaper*, she has written extensively about all areas of design. Rosa has been speaker and moderator for various design talks and conferences including London Craft Week, Maison & Objet, The Italian Cultural Institute (London), Clippings, Zaha Hadid Design, Kartell and Frieze Art Fair. Rosa has been on judging panels for the Chart Architecture Award, the Dutch Design Awards and the DesignGuild Marks. She has written for numerous English and Italian language publications, and worked as a content and communication consultant for fashion and design brands.