The Gee’s Bend quilters want you to visit them

For generations, the women of Gee's Bend, Alabama have created intricate quilts. Can tourism help preserve their traditions?

The route to Gee’s Bend, Alabama winds through forests of young longleaf pine and oak trees, and past acres of cotton planted in red earth. Buildings few and far between dot the road: low-slung homes, a brick church with a crisp white steeple, a two-pump gas station with a small grocery attached. And occasionally, a 10-foot-tall free-standing mural of a quilt appears.

A road in Gee's Bend, Alabama

Quilts helped to put Gee’s Bend, a remote enclave in Alabama’s Black Belt, on the map. These extraordinary textiles, a matrilineal tradition that began during slavery and has continued ever since, are prized around the world for their abstract patchwork and distinctive colours. And among Benders, as folks who hail from the region are known, they’re tangible representations of history, memory and kinship.

A billboard marking a stop on the Gee's Bend Heritage Trail. This one displays a work by quilter Ruth Pettway Mosely (1928-2006) that's now part of RISD Museum's collection

On a Saturday afternoon earlier this month hundreds of vibrantly hued and exquisitely patterned quilts were proudly displayed by their makers and the families that cherish them. Pinned on clotheslines and slung over porch railings, they fluttered in the breeze, drawing over 2,000 admirers from around the world for the fourth annual Airing of the Quilts Festival. The festival is an homage to a yearly tradition in Gee’s Bend when quilts would be taken from storage and aired before being used in winter. It is part of a new strategy to build a sustainable, equitable economy around Gee’s Bend quilts and deepen appreciation and understanding of the artistry and tradition they embody.

Colourful quilts float in the breeze during the annual Airing of the Quilts

An artistic tradition rooted in place

‘These quilts have brand recognition,’ says Kim Kelly, the executive director of the Freedom Quilting Bee Legacy, an organisation dedicated to preserving the legacy of Gee’s Bend and one of the festival’s organisers. ‘You say “Gee’s Bend”,’ and people know the brand but they don't really know where it is.’ And location, locals and advocates say, is essential to understanding what makes the quilts and their quilters remarkable.

Gee’s Bend quilts have had many lives since women in the region first began making them in the 19th century. Their beginning is rooted in survival and necessity, and is part and parcel with the history of the land. The name Gee’s Bend comes from Joseph Gee, a plantation owner and enslaver who bought 6,000 acres of land in the area in 1816. Gee’s Bend, so-named for a hairpin-turn in the Alabama River, is surrounded by water on three sides, with just one road leading out.

A view of the Alabama River from the Gee's Bend ferry

Because of a lack of written records, it’s difficult to say when quilting in the region began, but the oldest known quilter in Gee’s Bend is Dinah Miller, a woman captured in West Africa as a teenager and is believed to have arrived in Alabama in 1860 onboard the Clotilda, a ship that continued to traffic humans after the US banned the international slave trade, in 1805. 'She is patient zero when it comes to many of the renowned quilters and artists of this community,' Kelly says.

A quilter in Wilcox County (the county that holds Gee's Bend) displays her work in an undated photo, circa 1900

After Emancipation, the formerly enslaved people in Gee’s Bend remained as sharecroppers until the 1930s but their living conditions remained difficult. At that time, the region was one of the poorest in the country. Then the US government purchased the former plantation, in 1937, and provided low-interest loans for the families to buy the land as an economic relief lifeline. Ownership enabled Benders to remain during a time when most tenant farmers were displaced. Because of this, family traditions have been able to endure, quilting included, which is now at least in its seventh generation. ‘We’re taught that you have to fend for your family,’ recalls Kelly. ‘You got to learn how to cook, you got to learn how to keep a house, and you got to learn how to quilt.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The quilts’ patchwork design reflects the circumstances through which they were crafted. With very few resources, Benders made do with what was available to them, stitching together old clothing and cotton into quilts. The families used them for everything: to sleep under, to insulate their houses, as towels, as diapers. When the quilts became threadbare, families removed the worn sections and turned them into mops or burned them to smoke out mosquitoes. Because of this, the oldest surviving examples date from the 1920s.

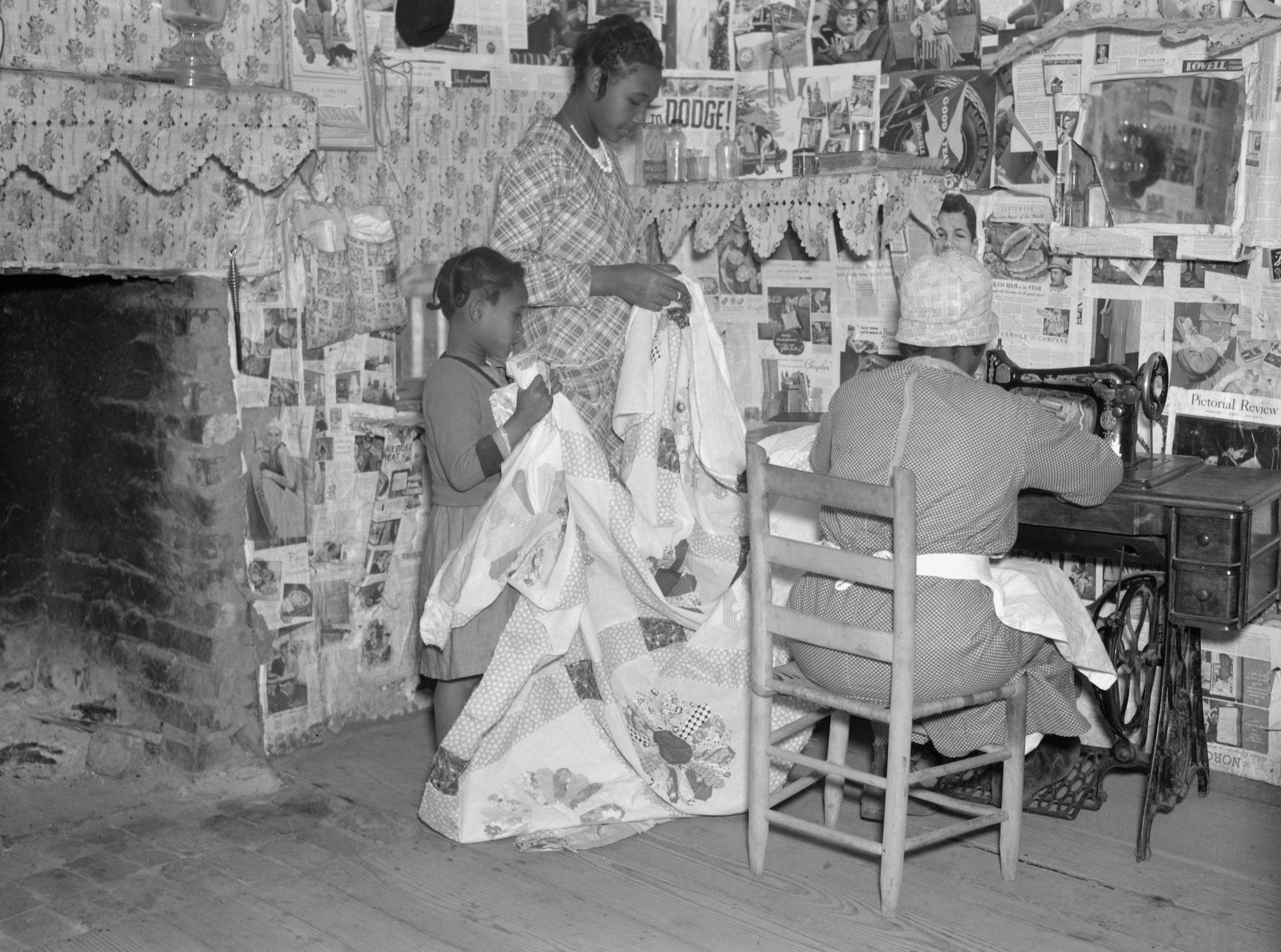

Lucy and Bertha Pettway help their grandmother, Lucy Mooney, create a quilt in 1937

Each quilter develops their own distinctive visual language – some preferring asymmetrical blocks of colour, improvisational ‘My Way’ designs, or angular patchwork. The patterns tell stories about what they feel or see, which is often objects or elements from the landscape. The quilts have names like Bricklayer, Housetop, and Log Cabin. The Housetop pattern of concentric squares is closely associated with quilters from the region. Today, roofs in Gee’s still reflect the jigsawing of different pieces of metal.

Families pass down similar techniques and quilters often collaborate with one another on designs. As William Arnett, a collector who helped bring Gee’s Bend quilts into major museum collections through a nonprofit called Souls Grown Deep, outlined in his 2006 book Gee’s Bend: The Architecture of the Quilt, the quilters think of their process much like builders, comparing their assemblage of ‘blocks’ – smaller sections of a quilt that are stitched together to form the whole – to laying planks on a floor. But a step more symbolic than that, he wrote, is ‘the ways in which Gee’s Bend quilts are conceived and built ultimately [becoming] structures that organise identity and affirm human relationships’.

‘It's in my blood. It's a part of my DNA’

Loretta Pettway Bennett, Gee's Bend quilter

These relationships span time and space, and involve direct experience or intergenerational memory. ‘Whatever we are thinking about or what's going on in our lives, we typically put it into the quilt, sometimes not even knowing it,’ says Loretta Pettway Bennett, a 65-year-old quilter. ‘I tell people, it's in my blood. It's a part of my DNA. And I see it in my granddaughter, even though she’s four years old. When she was three, I started her threading needles.’

Mary Margaret Pettway (left) and Shontaye Mosely (right) create a quilt together

Bennett’s latest quilt is a collaborative design with a dozen other descendants of Dinah Miller, the first known named quilter. In honour of their common ancestor, they each stitched blocks out of thrifted clothing, which Bennett then sewed together. Recently, quilter Mary Virginia Pettway, who is also in her sixties, designed a piece that commemorated the lives lost during the Middle Passage, the deadly transatlantic voyage enslaved Africans endured en route to America. Pettway assembled strips and triangles of blue denim, then joined the quilt together with curved running stitches to represent the ocean and its waves; a sole red stripe in the centre symbolises the people who died along the journey. Both quilts, along with many more, appeared in ‘Between History and Memory: Dinah Miller’s Legacy In Gee’s Bend’, an exhibition at the Gee’s Bend Welcome Center curated by Emma Yau of Souls Grown Deep, which is currently working to bring more scholarship to the history of Gee’s Bend as well as its contemporary artists.

An exterior view of the Freedom Quilting Bee in 1974

An economic lifeline

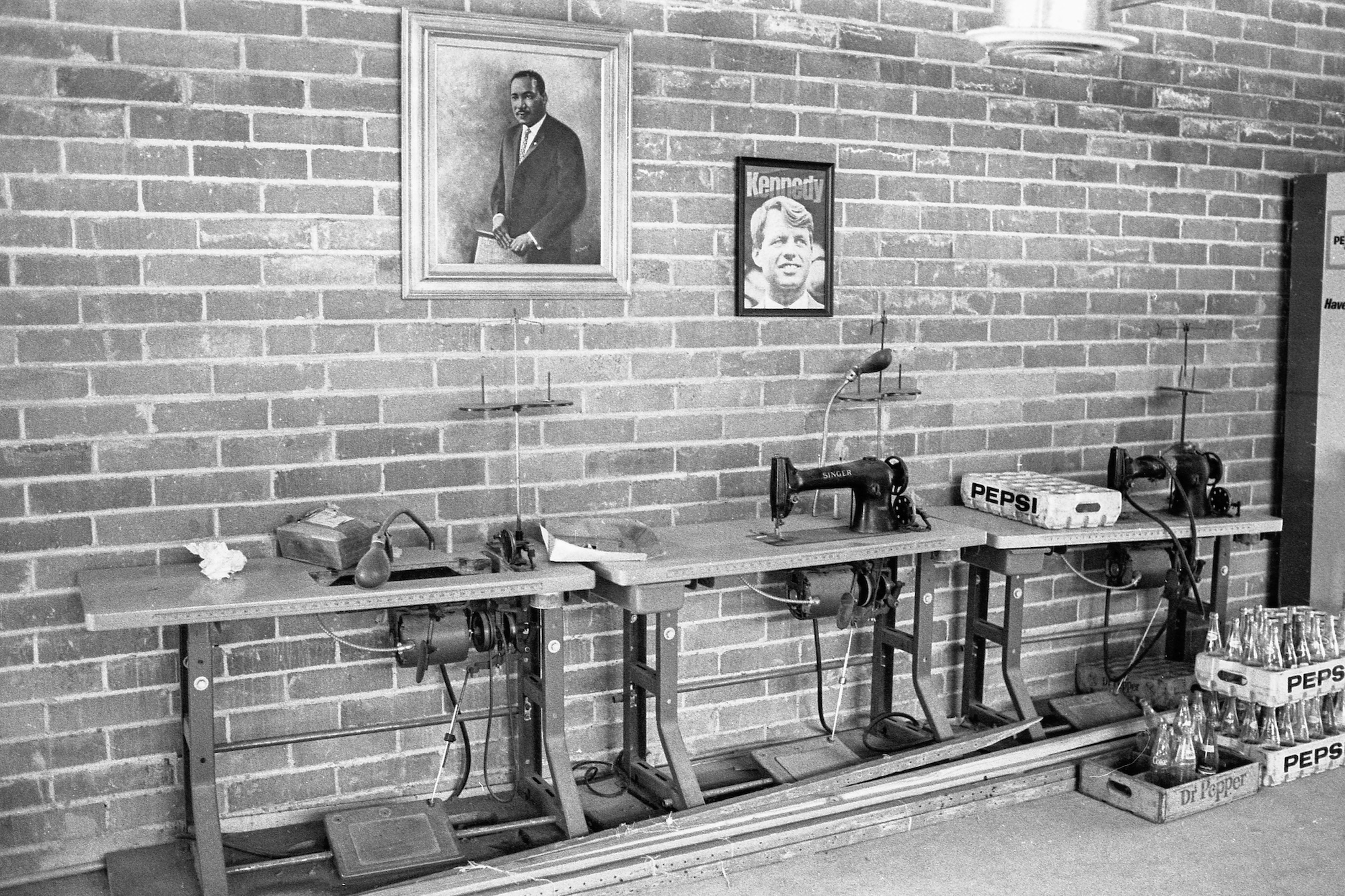

In 1966, 60 quilters formed a worker cooperative, the Freedom Quilting Bee, to turn their expertise into a living. It was a direct response to the Civil Rights movement. At the time, voter suppression tactics targeted Black residents of the surrounding Wilcox County, who had just gained the right to vote. They faced evictions, mortgage foreclosures, and job loss; a few years prior, the town of Camden, across the river from Gee’s Bend, eliminated ferry service to make it harder for its residents to vote and access services. Local civil rights leaders encouraged the women to sell their work in order to become more economically independent.

Amelia Bennett working at the Freedom Quilting Bee in 1974

The Freedom Quilting Bee produced pieces for department stores like Saks Fifth Avenue, Bonwit Teller and Sears, developing new types of quilts to make their work more marketable, including smaller quilts for baby beds, wall hangings, and tablecloths. At its peak, the collective employed 150 women. ‘Manufacturing brought to the families an amount of wealth they had never envisioned,’ Kelly says. ‘They were able to install plumbing in their homes and buy refrigerators and washing machines. But one of the most important things they were able to do was send their children to college.’

In addition to being lucrative, it was also a socially progressive operation. The Freedom Quilting Bee also offered childcare and its formal structure enabled members to draw Social Security benefits. Their industry thrived until the mid-1980s, when offshoring decimated stateside manufacturing and longtime partners did not renew their contracts. After the North American Free Trade Agreement was signed, Freedom Quilting Bee essentially stopped manufacturing, though it stayed open through 2010.

An interior view of the Freedom Quilting Bee in the 1970s

It is only recently that the quilts have become widely celebrated internationally as works of art. After appearing in exhibitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Whitney Museum of American Art in the early 2000s, the profile of the quilts exploded. Oprah Winfrey featured the quilters on her show, as did Martha Stewart. They appeared on US postage stamps – the first time work by living artists was featured on them –and began to enter the collections of prominent museums, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the de Young Museum and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Today, the quilts are represented in the collections of 40 museums on three continents. In 2022, they were the subject of an exhibition at Tate Modern, and in 2025, they featured in exhibitions at the Irish Museum of Modern Art and the Armory Show in New York.

But the increased recognition and appreciation of Gee’s Bend quilts hasn’t always benefitted the quilters equitably. In the aughts, three quilters sued Arnett, the collector and founder of Souls Grown Deep, alleging they were cheated out of compensation for their quilts and the use of their images; one said she was forced to sign a copyright document she couldn’t read (Arnett died in 2020). In 2008, the suit was dismissed. And copyright and licensing terms aren’t favourable to the quilters – if there’s a formal agreement at all. (Souls Grown Deep has served as an intermediary between quilters and institutions and collectors who wish to buy the quilts, encouraging the quilters to price their work commensurately with the caliber of their artistry.)

A quilter stitches pieces of a quilt together by hand

‘There have been many times where people come, take the art, and we never hear from them again,’ says Claudia Pettway Charley, a fourth-generation quilter and co-founder of Sew Gee’s Bend Heritage Builders, a new non-profit she, fellow Benders, and their descendants founded to help the community develop more sustainable and equitable business partnerships. Recently this included collaborations with Chloé, the fashion designer Greg Lauren, Dedar and Stephen Burks Manmade (previewed at the 2025 Venice Biennale) and Adidas, which also sponsored the 2025 edition of the Airing of the Quilts.

Meanwhile, most museum collecting to date has focused on older quilts and the artists who appeared on the postage stamps. More recently, non-profits have helped quilters to sell directly to customers through initiatives like Etsy storefronts and at events like the Airing of the Quilts.

Mary Margaret Pettway at work on a quilt

However, sales can still be uneven. At the festival, Marlene Bennett Jones, a quilter born in 1947, stitched away on a black, purple, and white piece stretched on a frame made from PVC pipes while surrounded by family, friends, and dozens of quilts swaying in the wind. For Jones, quilting is a source of pride and a passion more so than a viable way to make a living. While some museum-quality quilts can fetch $50,000, those rates are rare. ‘It’s like being a starving artist,’ Jones says. ‘If you wait to sell something, you will starve.’

‘Working on a quilt, it takes your mind off everything, off all your problems and all your situations’

Lue Ida McCloud, Gee's Bend quilter

Recently, various groups involved with Gee’s Bend have rallied around a new strategy to develop an economy around the quilts: cultural tourism. The hope is that more visitors will come to the area to buy quilts, attend workshops and retreats, and gain an understanding of the work that can only be appreciated in person, directly from the culture bearers themselves. ‘We don't want people in the world to think that this place is like some ethereal thing that you can't touch,’ Kelly says. ‘It is alive, it's living. It has always been alive and living for over 200 years.’

Lue Ida McCloud, a 74-year-old quilter who was born in Gee’s Bend, echoes Kelly’s sentiment about how open quilters in the region are. ‘We’re just a group of people, we love what we do, and we try to help whenever we can,’ McCloud says. Her classes have included quilters as far away as London and Greece. 'I just love doing what I do,' she reiterates. ‘Working on a quilt, it takes your mind off everything, off all your problems and all your situations.’

Reintroducing Gee’s Bend

Gee’s Bend is remaking itself into a visitor-friendly destination. It’s aligned with a strategy happening across Alabama, and the Deep South: heritage tourism is becoming a tool for revitalisation and economic development, with initiatives like the Legacy Sites, in Montgomery, and the Africatown Cultural Mile, in Mobile. If the region’s fame from postage stamps and museum exhibitions could help restore ferry service in 2006, after a 40-year shutdown, what else could increased visibility accomplish? The town recently unveiled the Gee’s Bend Heritage Trail with funding from Souls Grown Deep, a self-guided driving tour.

Another quilt on the Gee's Bend Heritage Trail. The billboard celebrates Jessie T Pettway. Her quilt, created in the 1950s, is now in the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

This year, the Freedom Quilting Bee Legacy renovated and reopened the original building where the collective manufactured quilts to visitors. It now features a shop, an exhibition, and quilting demonstrations. ‘Many people look at meeting a Gee's Bend Quilter as a bucket-list item,’ Kelly says. ‘I would see ’em driving up and down the road with out-of-state licence plates. I knew what they were looking for, but other than the Quilting Collective, which is up the road and whose hours are kind of haphazard, there was no place to connect to these people.’

And last year, Souls Grown Deep opened a new art gallery in Gee’s Bend to give visitors and locals alike another destination to connect with the history and culture of the region. ‘There's a whole roster of [Gee’s Bend] exhibitions, but so much of that was done outside of this community,’ says Raina Lampkins-Fielder, chief curator at Souls Grown Deep. ‘We wanted to do it here so that people can see the history and the artistry that is continuing. It’s living.’

During the airing of the quilts, artists display their works on clotheslines throughout Gee's Bend

It’s working. The main event is the Airing of the Quilts. In addition to becoming an open air gallery where visitors can admire and purchase quilts – over 80 quilters offered everything from $20 machine-stitched potholders to hand-sewn full-sized quilts going for tens of thousands of dollars – the festival featured live quilting demonstrations and workshops, live music, and food.

It’s attracting visitors from around the world. On my flight to Alabama, I sat next to a woman from Los Angeles who organised a family reunion in Gee’s Bend in honour of her grandmother, who loved quilting. And at my Airbnb in Selma, I met a group of quilters from North Carolina who turned their desire to see the festival into a road trip.

Inside the Gee's Bend Welcome Center

Quilters of all stripes – the famous ones represented in museums as well as artists who have moved to the area to immerse themselves in the tradition – proudly displayed their handiwork. The home of Mary Lee Bendolph, a quilter who was featured in a Pulitzer-winning Los Angeles Times story and named to this year’s Forbes 50 over 50 list, is on the Gee’s Bend Heritage Trail. For the festival, she and her daughter, Essie Bendolph Pettway, strung up quilts the two had made together. From their perch on Bendolph’s porch, they greeted admirers who hopped off tour shuttles to see their work up close. Bendolph, who is now in her nineties and has dementia, still stitches blocks, but no longer makes full-sized quilts on her own, Pettway explains to me. She’ll combine her blocks with her mother’s to finish a piece. After completing a design, she’ll share it with her mother, who offers creative feedback. After Bendolph said one design needed a little yellow and red, Pettway used those hues for the border.

An aerial view of the Airing of the Quilts Festival, a celebration that now draws international visitors

The festival has also become an important draw for the descendants of Gee’s Bend, lending it the feeling of a family reunion. Tangular Irby, who is Dinah Miller’s great-great-great granddaughter, is one such descendant. At the festival, she read from Pearl and Her Gee’s Bend Quilt, a children's book she wrote, and explained why documenting history to connect with the youngest Benders is important. ‘My biggest regret, having grandmothers that were Gee's Bend being quilters, is I never learned to quilt from them,’ she told the crowd. ‘Why? Because as a child, I didn't know that was special.’

Sustaining the community

As the business of Gee’s Bend grows, whether from tourism or through partnerships, the hope is that the gains can be reinvested directly into the community so that it remains a vibrant place for all generations. Despite international acclaim, the lack of basic infrastructure (Gee’s Bend still doesn’t have services like street lights, sidewalks or a community center) is a reminder of systemic neglect and that cultural heritage, however priceless, doesn’t translate to dollars and cents.

The beginning of the Heritage Trail starts with a history display at the Gee's Bend Welcome Center

Right now, the Gee’s Bend Welcome Center, which is oriented toward tourism, has served as a makeshift community center, but it has been a tight squeeze. ‘If we have a birthday party at the Welcome Center, then they have to dismantle the museum,’ Charley, the fourth-generation quilter and founder of Sew Gee’s Bend Heritage Builders, says. Additionally, since there is no place for women to drop in and quilt together, the art form has become a solitary activity. She hopes to build a centre with the proceeds that her organisation earns from collaborations.

Keeping Gee’s Bend at the heart of the region’s quilting tradition is central to recent advocacy efforts. ‘It's important for rural communities to see that you don't have to be in a big city to benefit wherever you are in life,’ Charley says.

Diana Budds is an independent design journalist based in New York