How Achille Castiglioni helped shape postwar Italy with enduring design

Everything you need to know about Achille Castiglioni, the Italian designer whose works – honest and punctuated by playfulness –helped shape a country

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

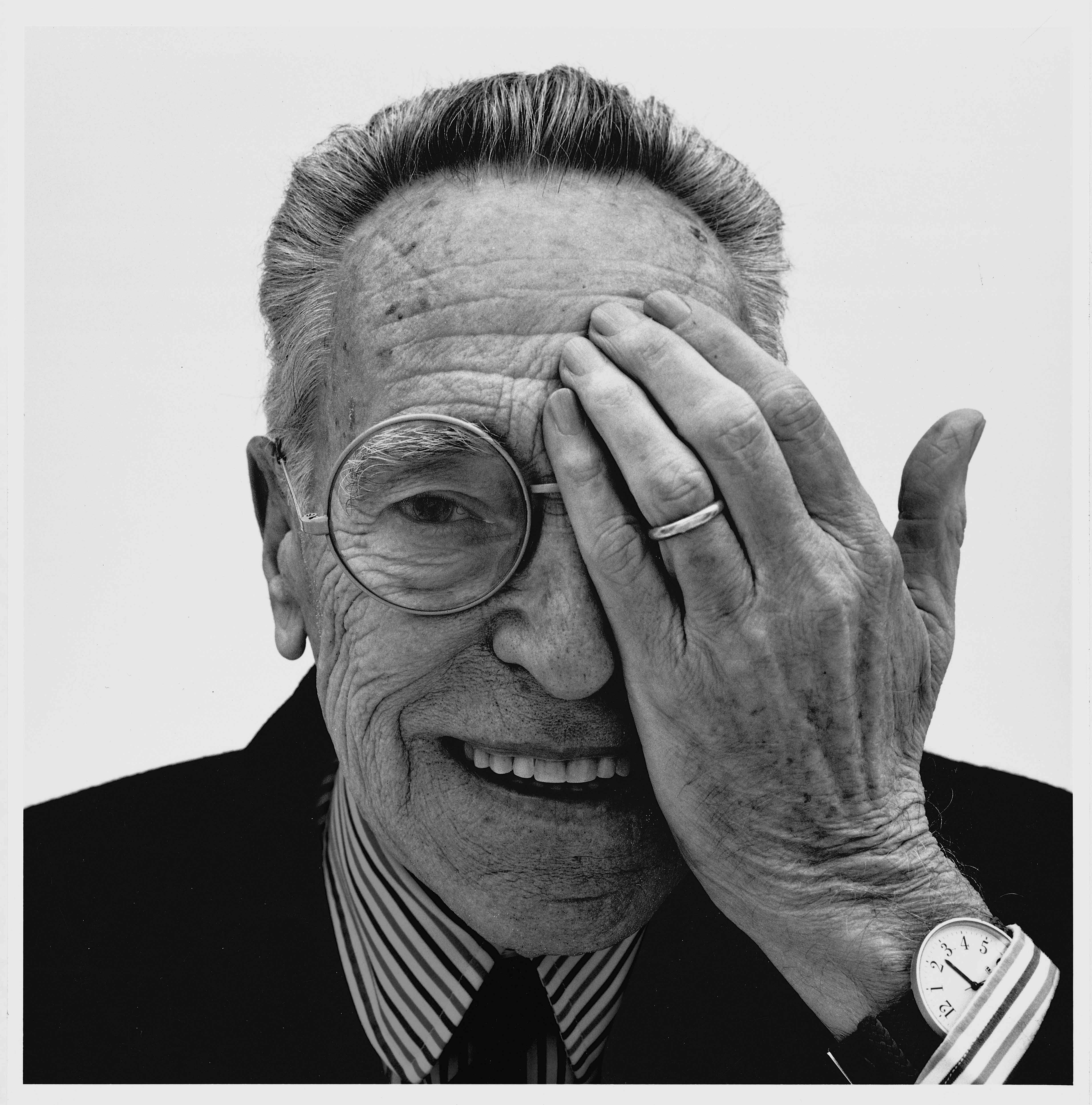

When talking about Italian design in the postwar period – the so-called ‘economic miracle’ that transformed Italy from a war-torn nation to a production powerhouse – it’s impossible not to mention Achille Castiglioni.

The Milan-born designer encapsulated so many of the qualities that defined the era. He was resourceful, inventive, playful, but above all curious about the possibilities of the future. He spent his career finding new uses for ordinary things and transforming them into icons, blurring the boundary between play and function, and proving that utility needn’t be dull. Awarded the Compasso d’Oro nine times, he also shaped generations of designers through teaching, emphasising curiosity and the power of stripping away the unnecessary.

Achille Castiglioni’s early life and education

Achille Castiglioni was born in Milan in 1918, the youngest of three brothers in a family steeped in the arts. His father, Giannino, was a sculptor and goldsmith, while his mother, Livia, encouraged creativity in the home. The Castiglioni household provided fertile ground for invention, and Achille grew up in a world where drawing, making, and experimenting were part of daily life.

After completing classical studies, he enrolled in architecture at the Politecnico di Milano, graduating in 1944. His studies were interrupted by wartime service, but even as a student, he was fascinated by ordinary objects. He collected simple, everyday things not as curiosities but as examples of clever problem-solving. This habit of recontextualising the everyday would remain central throughout his career.

The Castiglioni brothers: Achille, Livio and Pier Giacomo

Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni

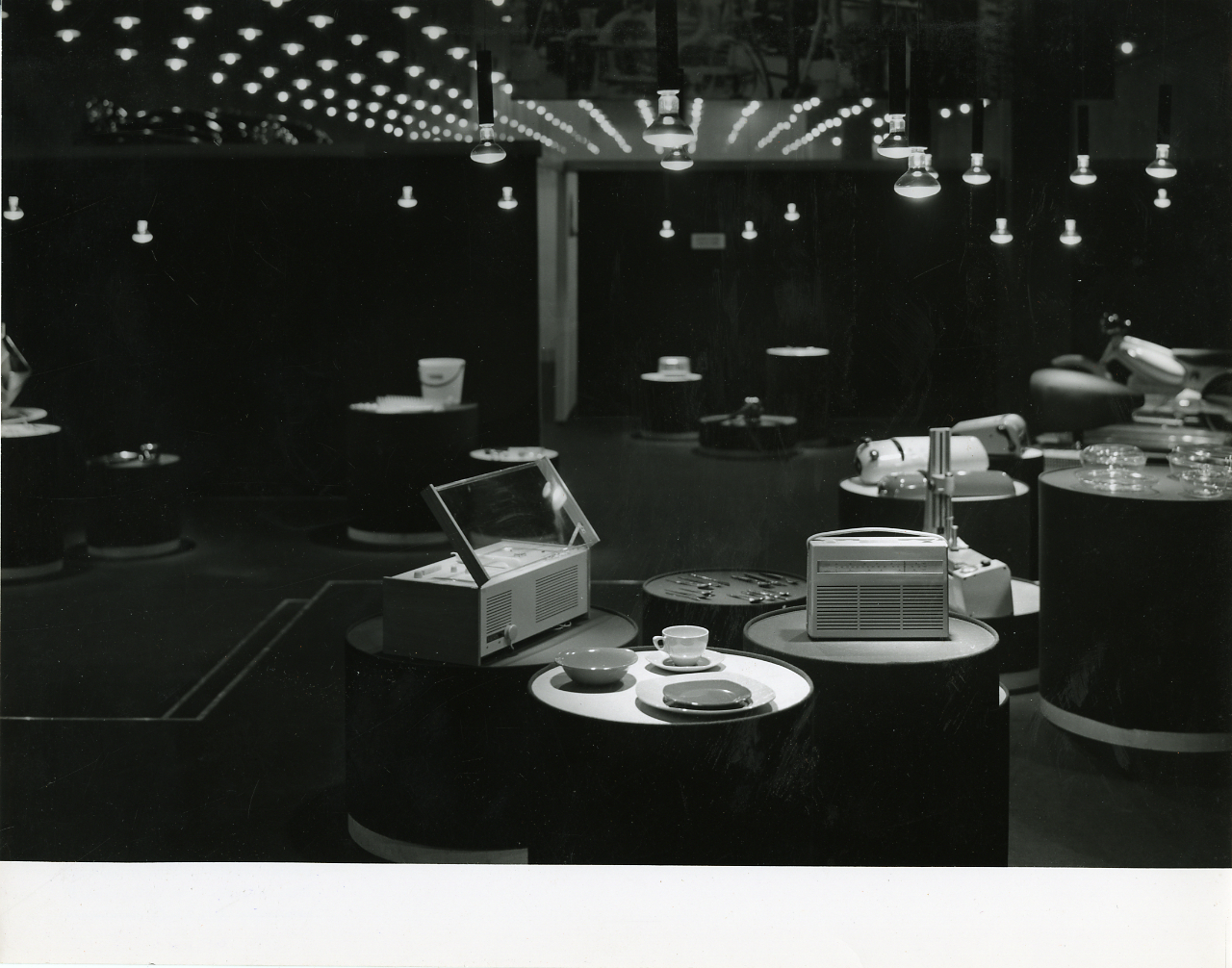

In 1944, Achille joined his elder brothers Livio and Pier Giacomo in their Milan studio. The trio’s early projects were pragmatic: exhibition stands for trade fairs, interiors for public buildings, and product designs for manufacturers eager to reach a newly modernising Italian public. Livio was more technical, Pier Giacomo more methodical, and Achille more playful. Together, they developed a style that was functional, unpretentious, often humorous, and always guided by common sense.

A 1954 display at Triennale Milano showcasing industrial design by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni

By the early 1950s, Livio had stepped away to pursue independent work, leaving Achille and Pier Giacomo to forge one of the most important design duos of the century. Their studio on Corso di Porta Nuova became a hive of invention, and when that building was demolished in 1962, they relocated to Piazza Castello 27. That space would remain Castiglioni’s base for the rest of his life and still operates today as a museum dedicated to his work. After Pier Giacomo’s death in 1968, Achille kept the practice alive on his own, continuing to collaborate with Italy’s leading manufacturers while also expanding into teaching.

Repurposing the ordinary

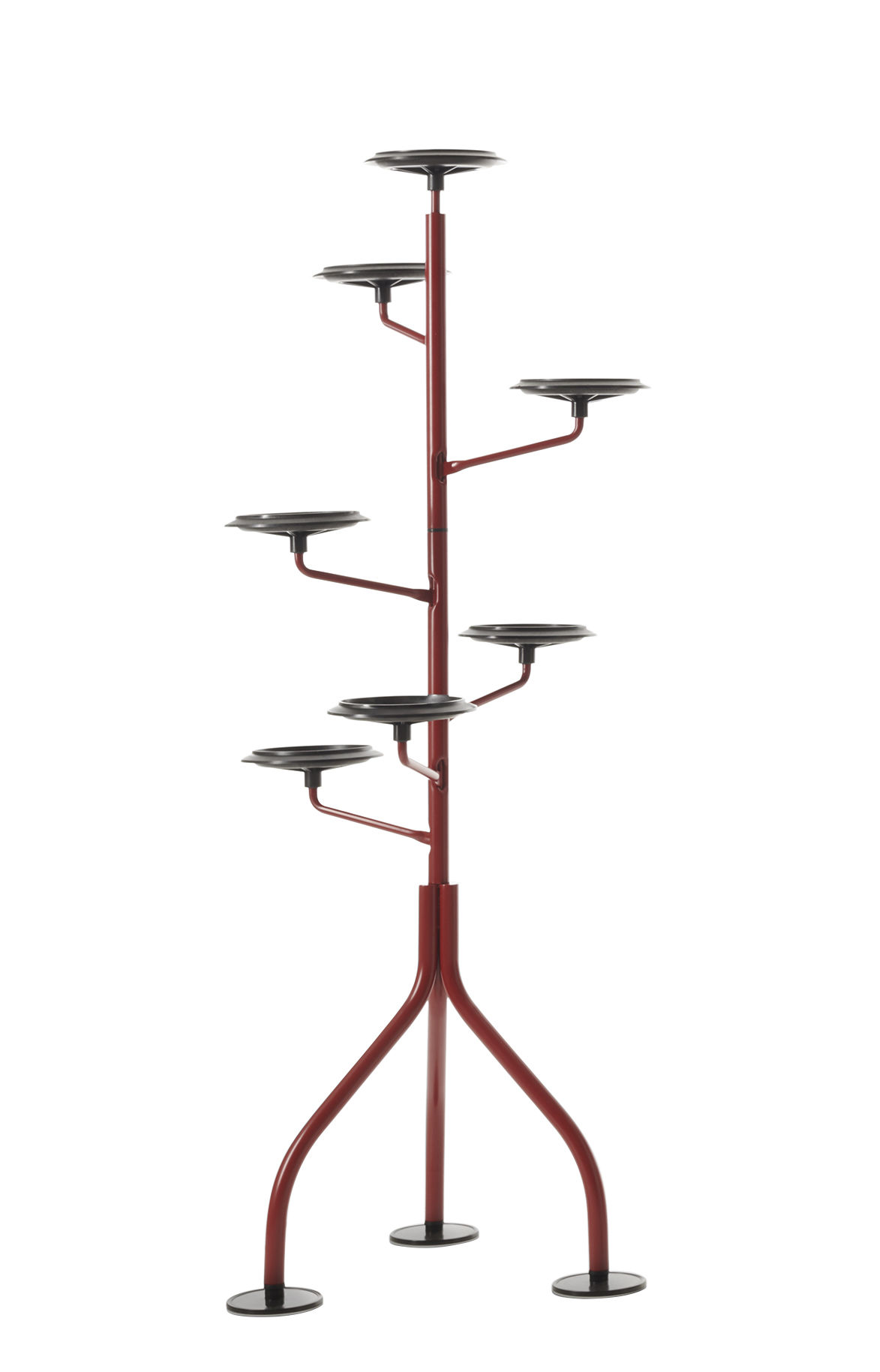

'Interruttore rompitratta', a light switch designed by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni in 1968

Nothing is more associated with Castiglioni than his gift for finding new life in familiar parts. Following in the footsteps of Marcel Duchamp’s readymade artworks, he and Pier Giacomo began incorporating found objects into their designs.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘Mezzadro’ stool, 1957

With ‘Mezzadro’ (1957), a tractor seat is lifted from the farmyard and placed atop a sleek steel stem and wooden footrest, turning a utilitarian fragment into domestic seating. The ‘Sella’ (1957), a stool made from a leather bicycle saddle balanced on a slim stem and weighted base, encourages a kind of half-perch, half-ride, effectively creating a design that prioritises play as much as practicality.

Light as architecture

‘Arco’ (1962)

Castiglioni’s approach to lighting was nothing short of architectural. His most famous lamp, the ‘Arco’ (1962), is essentially a ceiling lamp without a ceiling, its long steel arch cantilevered from a marble block so the light falls gracefully over a dining table or sofa.

‘Taccia’, 1962

Similarly, the ‘Taccia’ (1958), with its glass bowl reflector set askew on a fluted base, casts an atmospheric glow via a blanket of indirect light. For Castiglioni, light wasn’t just illumination, it was a way of shaping space and transforming the feel of a room with a single gesture.

Architecture and urban planning

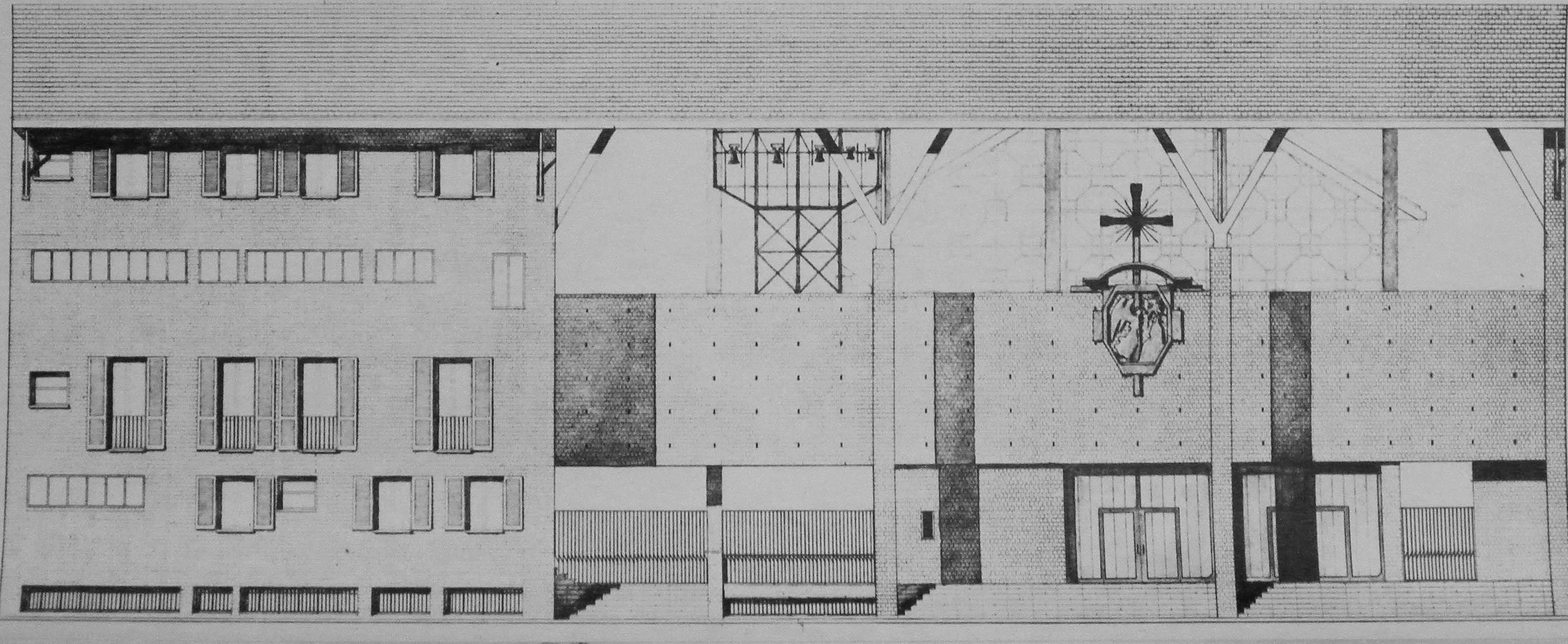

Original drawing for the church of San Gabriele Arcangelo in Mater Dei in Milan

Although Castiglioni is most celebrated for his industrial design, his career began with architecture and exhibition design. Among his an Pier Giacomo’s best-known architectural works are the Chiesa di San Gabriele Arcangelo in Mater Dei in Milan (1956), a church that balanced modernist lines with an intimate human scale, and the redevelopment of the Palazzo della Permanente (1953), an exhibition space destroyed during the war and later rebuilt as a showcase for contemporary art and design.

Teaching and influence

My method is to take out again and over again, until I will find the main design component: a minimum sign or a minimum shape required by the function. I want to get to say: less than this, I can’t do it

Achille Castiglioni

From 1980 onwards, Castiglioni brought this philosophy into the classroom at the Politecnico di Milano, where he taught industrial design until the early 1990s. He encouraged what he called 'design by subtraction', the art of stripping away everything unnecessary. He once said: 'My method is to take out again and over again, until I will find the main design component: a minimum sign or a minimum shape required by the function. I want to get to say: less than this, I can’t do it.'

Many students carried his influence into their own practices. The architect Patricia Urquiola, among the most prominent, has spoken often of his mentorship, recalling how he taught her to see humour and humanity as essential elements of design. Through teaching, Castiglioni extended his reach beyond objects, shaping generations of designers who continue to carry his philosophy forward.

Fondazione Castiglioni: a designer's legacy

Castiglioni died in 2002, but his Milan studio remains intact as the Fondazione Achille Castiglioni. The atmosphere inside was famously informal and that feeling has been carefully preserved. Drawings are pinned to walls, prototypes lay scattered across workbenches, and objects of all kinds – from toys to tools – fill the shelves.

Visitors can still walk through what is essentially a living archive, witnessing the same curiosity that fuelled his career. It is a fitting tribute to a designer who never stopped asking questions, and who found magic in the most ordinary of things.

Fondazione Achille Castiglioni, Piazza Castello 27, 20121 Milano

Six Achille Castiglioni designs to know (and own)

The ‘Arco’ floor lamp, designed in 1962 with Pier Giacomo, remains one of the most iconic pieces in modern lighting. Its long stainless steel arch extends gracefully from a solid block of Carrara marble, allowing light to be projected over a dining table or sofa without the need for a ceiling fixture.

The RR126 stereo system (1965), designed with Pier Giacomo, redefined hi-fi as furniture. Its speakers could be detached and positioned freely, even used as side tables, making technology adaptable to domestic life. A 60th anniversary version limited edition (in green) was recently released.

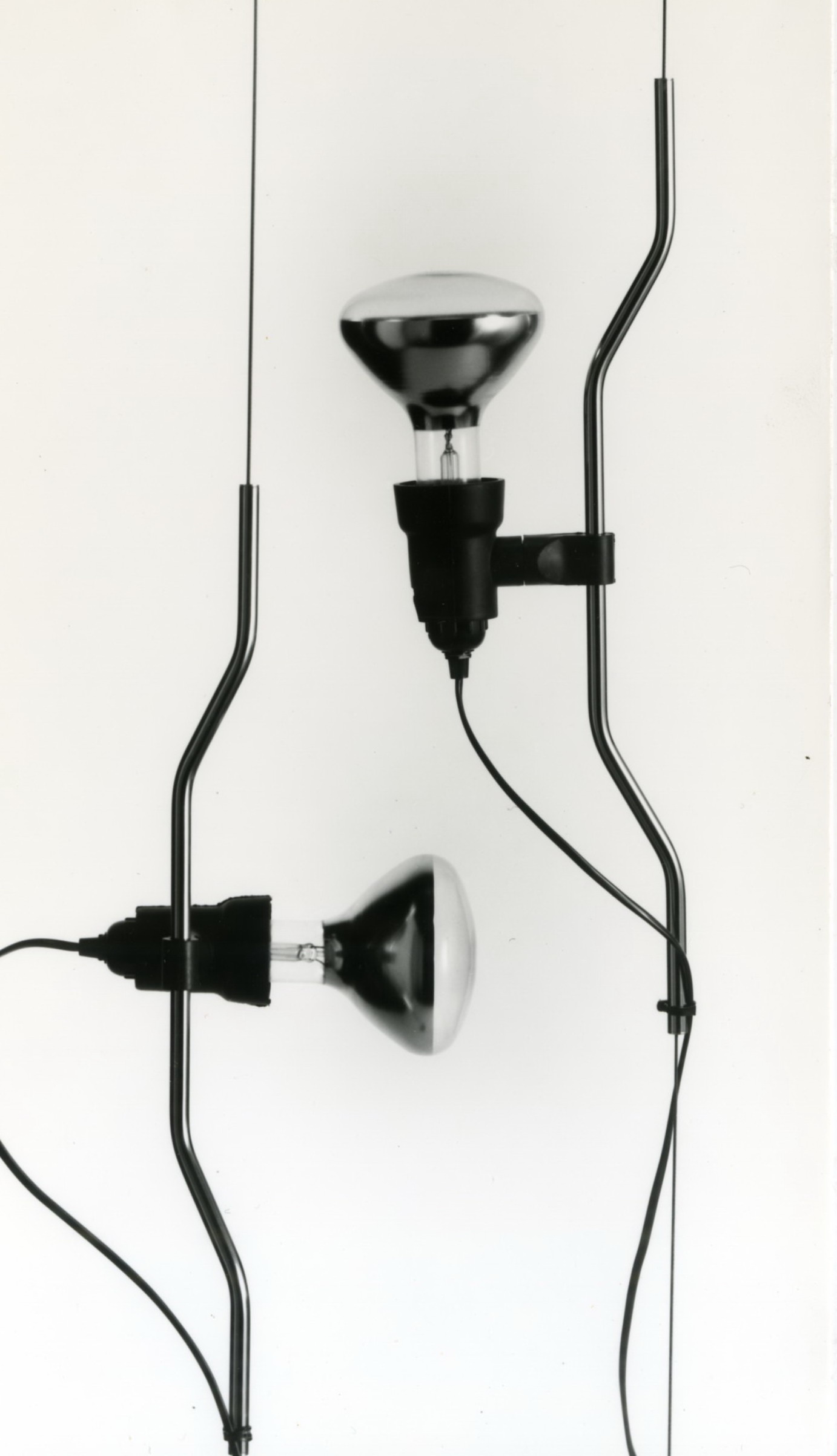

The ‘Parentesi’ (1971), designed with Pio Manzù, is one of Castiglioni’s most inventive lighting concepts. A steel cable stretches taut from ceiling to floor, while a cylindrical lamp head slides freely up and down the line. The name comes from the Italian word for ‘parenthesis’, referencing the curved tube that grips the cable and holds the lamp in place.

The ‘Snoopy’ (1967), designed with Pier Giacomo, is a playful desk lamp that pairs a heavy Carrara marble base with a glossy enamelled metal shade. Its cartoonish silhouette, in the shape of its namesake beagles’ nose, and clever indirect light make it one of Castiglioni’s most beloved designs.

Laura May Todd, Wallpaper's Milan Editor, based in the city, is a Canadian-born journalist covering design, architecture and style. She regularly contributes to a range of international publications, including T: The New York Times Style Magazine, Architectural Digest, Elle Decor, Azure and Sight Unseen, and is about to publish a book on Italian interiors.