Tracey Emin lays bare her own traumas in piercing new show

The British artist is as deeply personal as ever in her first London exhibition in five years, reflecting on loss, mourning, insomnia and spiritual love at White Cube Bermondsey

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

‘Our lives are in a trilogy. I’m in my last bit, so I’ve got to try and get it right,’ Tracey Emin reflects on the eve of her new solo exhibition, which has just opened at London’s White Cube Bermondsey. What’s the overriding theme of the exhibition? Herself. Because after all, Emin is what Emin does best.

In the 1980s, she emerged as the fresh faced enfant terrible of the Young British Artists movement. Four decades later and she’s still charged with the same acerbic bite – an unflinching exhibitionist who manages to exhibit both her self and work in a single space. Much to the relief of her admirers and critics, Emin has emerged from her sabbatical no less explosive albeit older, wiser and less of a ‘party girl’. The passion with which she visually and verbally dissects everything from ‘hideous’ Brexit to abortion, rape, relationships and her mother’s death is itself sobering to witness.

But the captivating candidness and apparent self-annihilation that earned her public notoriety in youth are not moments she reflects on fondly. ‘I suddenly woke up one morning and realised that I’d really fucked myself over by talking too much... by giving too much away,’ she recalls. But here, within the walls of White Cube it feels as though Emin is entirely in control of her work and self-image – as she puts it, ‘getting her act together’. ‘What this whole show is about is releasing myself from shame. I’ve killed my shame, I’ve hung it on the walls,’ she explains.

It was all too Much, 2018, by Tracey Emin, acrylic on canvas. © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2017. Photography: Theo Christelis. Courtesy of White Cube

Sprawling over 5,440 sq m of White Cube, the artist’s first London show in half a decade feels like a homecoming – a culmination of new and historical painting, photography, film, large-scale sculpture and neon text, of course, the 21st-century answer to Dada’s Readymade. The idea for the exhibition title, ‘A Fortnight of Tears’, long preceded the majority of this work’s creation. She’s had this one in the bank for 15 years, tentatively awaiting the right time to deploy it. ‘It’s the longest I’ve ever cried for I think, a fortnight,’ she says.

Themes in the exhibition stem directly from the artist’s own emotions: the loss of her parents and her ‘self-respect’, the female experience, spiritualism and sexuality. Three monumental bronze sculptures – including one portraying her mother in her eighties – are the largest Emin has produced to date. These sit adjacent to new a photographic series Insomnia (a four-year work in progress) alongside a vast quantity of paintings, studies and artefacts including a Ouija board. An early video work How It Feels (1996), chronicling Emin after her harrowing 1990 abortion, is shown in tandem with The Ashes, a new film work shot in the artist’s east London home. The camera pans over a scene in Emin’s light-drenched dining room where her mother’s ashes sit in a wooden box.

I’ve killed my shame, I’ve hung it on the walls.

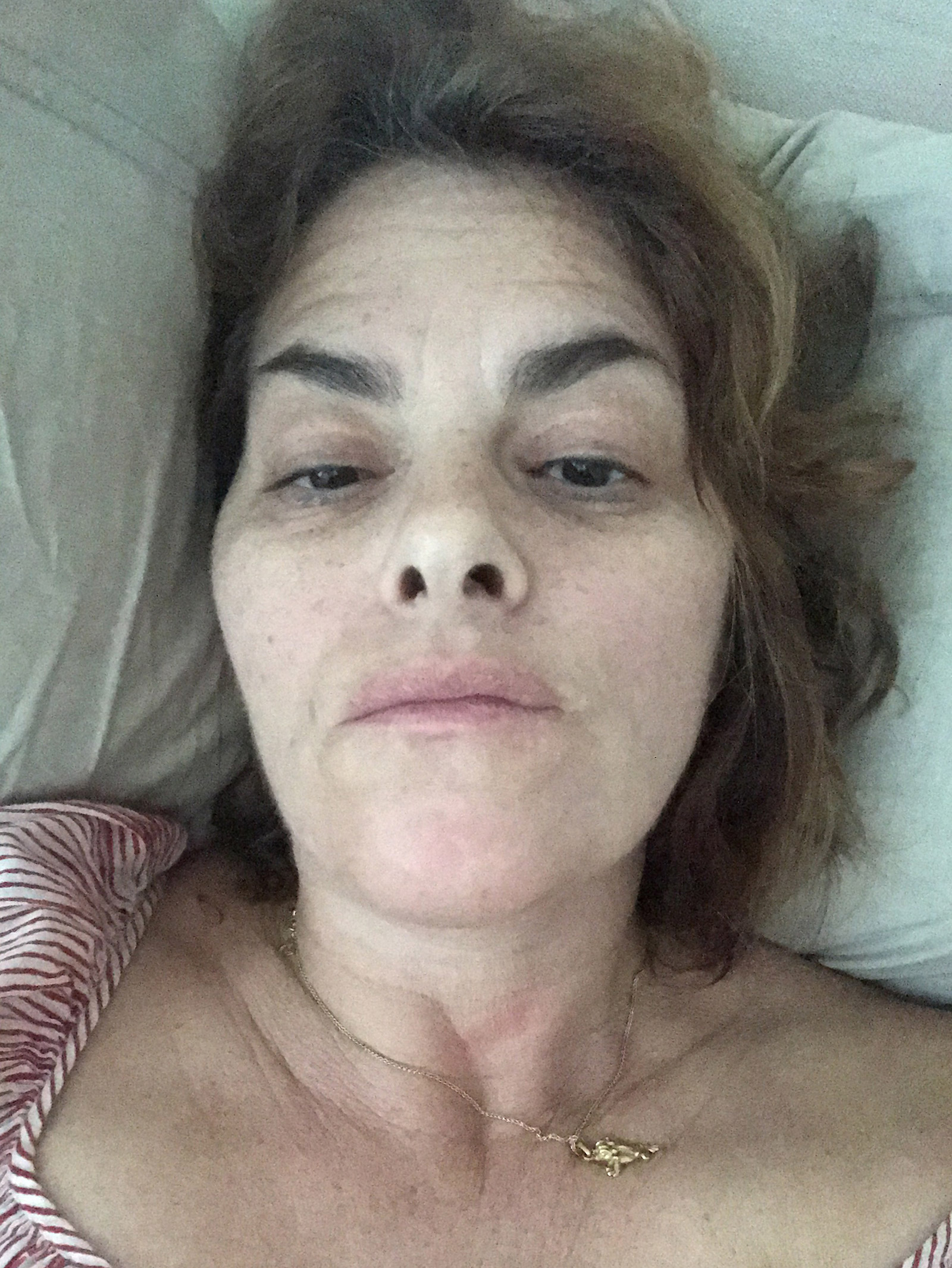

In the first gallery, visitors are reacquainted with the artist’s infamous bed – but this time it’s Emin in bed, 50 times over in a grid of self-portraits on the gallery’s walls. This format is nothing fundamentally new: Emin has been performing the selfie before the selfie was even born. In these portraits, viewers become intimately acquainted with Emin’s surgery scars, facial lacerations and cyclical changes in mood and nightwear.

Some are humorous, some are haunting and one was taken the night she knew her mother had died. This is the ongoing Insomnia series, which sees Emin alone, tormented by fatigue but incapable of sleep. ‘I had it [insomnia] in my early twenties in art school, but I loved it then, I could do whatever I wanted and it seemed that I had more hours in the day. As I’ve got older it’s got more and more soul destroying. Insomnia is not an affectation, it’s crippling,’ she says.

Insomnia 14:39, 2018, by Tracey Emin, Giclee print. © Tracey Emin. Courtesy of White Cube

But it’s Emin’s paintings that steal the show, both in their immense quantity and volatile passion. They Held Me Down While He Fucked Me 1976 and But You Never Wanted me (both 2018) are two of the many portraits depicting gestural female nudes – presumably Emin – reclining, sleeping, bleeding and masturbating. The paint seeps in visceral layers riddled with trauma, rage, rejection and sexual aggression – Schiele-esque in twisted, gritty composition and Munch-like in eerie dilution.

With its acute commentary on the extremities of the female experience, it’s difficult to avoid drawing parallels with the today’s #MeToo and Time’s Up movements. ‘I kept trying to say [this] to people years ago’, Emin exclaims. ‘Suddenly I’m allowed to express myself and to have the language and the voice that I’ve had for years and years. Now we’re in a time where we can put things right, and this is what my work is about.’

So once again, we’re voyeurs in the next phase of this turbulent artistic existence, no less gripped, but perhaps now a little more empathetic. The White Cube show feels far beyond raw personal confession and seems to assert the precision and complexities of the broader human experience. ‘I don’t have anything else in my life,’ she says, ‘my work has completely taken over now and I’m completely dedicated to it.’

You Kept watching me, 2018, by Tracey Emin, acrylic on canvas. © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2017. Photography: Theo Christelis. Courtesy of White Cube

Installation view of ‘A Fortnight of Tears’ at White Cube Bermondsey. © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2017. Photography: Ollie Hammick

INFORMATION

‘A Fortnight of Tears’ is on view from 6 February – 7 April. For more information, visit the White Cube website

ADDRESS

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

White Cube Bermondsey

144-152 Bermondsey Street

London SE1 3TQ

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.