American avant-garde artist Senga Nengudi receives top billing at last

We explore the work of American artist Senga Nengudi, who has just opened two major shows in New York, and will be awarded the Nasher Prize for Sculpture 2023 in April

Photography: Camila Falquez

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

In 1971, the African American artist Senga Nengudi participated in a group show at the Musée Rath in Geneva, showing, for the first time, a body of work called the Water Compositions. Consisting of heat-sealed plastic filled with water that had been dyed with Easter egg colouring, the forms evoked the softness and sensuality of the body in the manner in which they undulated and responded to touch. They exemplified a series of aesthetic threads that have characterised Nengudi’s practice in the five decades since, with its investment in ritual, the female body, and performance. In her sculptures, tactile elements establish an interface between the viewer and the space, explains Matilde Guidelli-Guidi, the curator of a monographic exhibition exploring Nengudi’s work, which opened in mid-February at the Dia Beacon, a former box-printing factory-turned-museum of modern art in the Hudson Valley.

Detail view of Nengudi’s Sandmining B (2020), an installation with sand, pigment, car parts, nylon mesh and sound

Nengudi, who is the recipient of the 2023 Nasher Prize for Sculpture, remembers the Geneva show as a rare opportunity at a time when Black artists were denied proper exhibition spaces. Called ‘8 Artistes Afro-américains’, the show, Europe’s first exhibition of work by Black American artists, was curated by Henri Ghent, the director of the Brooklyn Museum’s Community Gallery. Lise Girardin, then the mayor of Geneva, remarked that Ghent’s selections were too European and international in spirit, and that she had expected something ‘more original’ and ‘more Afro-American’. (Ghent, one of the first Black people to assume a decision-making post with a major American museum, was dismissed from his position the following year after differences with the museum’s new director. A New York Times letter to the editor from the time noted that it was frustrating to see how he was deprived of his ‘right to function as a creative individual within the white power structure’.)

Detail view of Sandmining B (2020)

Senga Nengudi, Wet Night–Early Dawn–Scat Chant–Pilgrim’s Song (1996), installation in progress

It was in this milieu that Nengudi arrived in New York in the early 1970s. Black artists were considered either downtown or uptown, the neighbourhoods signifying a practice rooted in an abstraction palatable to white audiences, or a commitment to a Black nationalism energised by the politics of the moment. Nengudi moved uptown, to Harlem, but was initially hesitant to show her work, worried that her peers wouldn’t understand it. ‘It was really a tricky thing, because my art wasn’t considered “Black” at the time,’ she remembers. Black artists were often relegated to what was known as a community room at larger museums – a token space, often in basements. ‘You never got up to the second or third floor,’ she says.

Born in Chicago and raised in California, Nengudi attended California State University in LA, where she was the only Black woman in the fine arts department. The experience was not without its indignities. At one point, a professor didn’t believe that she had produced a series of drawings for an assignment. Eager to position herself in a broader art history, she turned to books on African art, invariably written in French. The cruelness of their colonial point of view reduced her to tears. ‘There was no such thing as African American Studies at the time,’ she remembers. ‘It was like we didn’t exist.’

Detail view of Water Composition I (1970/2019), on show at Dia Beacon

Detail view of Water Composition II (1970/2019)

In the mid-1960s, Nengudi was teaching at the Watts Towers Arts Center in LA, when Marquette Frye, a 21-year-old Black man, was arrested for allegedly driving under the influence. The confrontation between him and the police was followed by a six-day uprising in the historically Black area of Watts. The moment was seismic for a number of Black artists in LA, for whom the uprising offered the opportunity to reflect on the meanings of their work, in relation to what was mainstream: ‘We don’t need you anymore, we don’t need to use the materials you use, or use the themes that you use, and so on. We can find ourselves, we can make do with what we have, and we can create from that,’ Nengudi recalls.

Shortly afterwards, she studied in Japan for a year, drawn to the minimalist elegance of the avant-garde Gutai group. East Asian influences persist in a body of work she created in the 1990s that returns to clear plastic. Folded in origami-style envelopes, the pieces are pinned to the wall and contain water, reactivating materials used in the Water Compositions, though in a slightly different way, Guidelli-Guidi suggests.

Guidelli-Guidi first encountered Nengudi in filmmaker Barbara McCullough’s 1979 documentary Shopping Bag Spirits and Freeway Fetishes, in which Nengudi is interviewed on the subject of her 1978 performance Ceremony for Freeway Fets, staged alongside other members of the art collective Studio Z in an LA underpass. Nengudi is first heard as a disembodied voice while images of her artworks are displayed on screen, including pieces that employ nylon stockings, a material that she has often used in ways that bring to mind splayed limbs or the feminine form. In the footage that follows, her face is obscured by layers of fabric. She is performing. Her voice, in the background, states that ritual involves doing things in a ceremonial way, and operating on a spiritual plane.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Senga Nengudi, Water Composition VI, (1969-70/2018)

Nengudi once wrote that creating works for posterity was not a priority for her. Yet her interest in the notion of ritual would suggest a belief in the permanent over the temporary. She cites the South Asian practice of rangoli, the creation of daily patterns in the entrance of the home with coloured sand – a woman’s creative work. Though the rangoli’s physical existence is short-lived, it achieves a form of permanence in that it has been repeated generation after generation. ‘We’re people, we do the same thing, we kill everybody, there’s war, war, war, war, war, there’s love, love, love, love, love, over and over and over again, and that’s the kind of permanence I’m thinking about,’ she explains.

This reflection upon the longevity of ritual through the use of ephemeral materials is present in room-sized installations at Dia Beacon: Sandmining B (2020), comprising sand, steel and nylon mesh, and Wet Night–Early Dawn–Scat Chant–Pilgrim’s Song (1996), a multi-part work that uses dry cleaning bags, bubble wrap, and spray paint on cardboard. There is a portability to the pieces, simple found objects and materials used effortlessly to create a call and response with the viewer. Guidelli-Guidi cites a remark by artist Lorraine O’Grady, who once said that Nengudi could fit her installations into a suitcase.

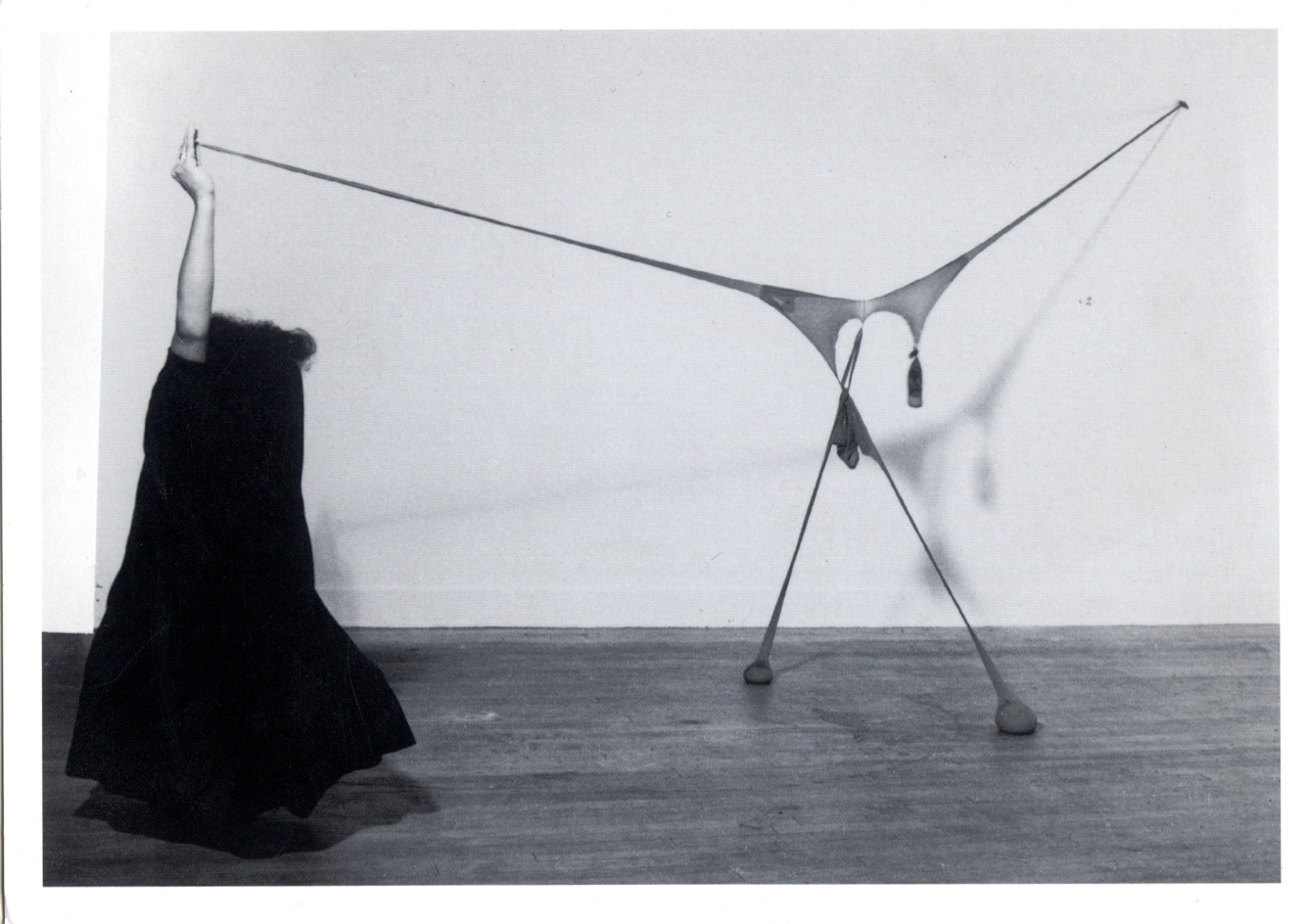

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978)

Nengudi describes the recent recognition of her work as a graduation of sorts, likening it to moving from the children’s table to the adult’s table at Thanksgiving dinner. Or, in a way that harkens back to the inequalities of the early years, a move, finally, to the third floor. ‘Oh my gosh, I’m here with these giants, it’s just amazing,’ she says. But Nengudi has been a giant in her own right for many years, writing herself into a canon for which there was no vocabulary before, among the critics who acted as power brokers in an art world that was overwhelmingly white.

It is the efforts of Black art theorists and historians who have been able to discuss her practice in layered terms, she believes, that has helped nurture a better understanding

of it. The works, many of them entering Dia Beacon’s collection after two years on display, are part of the museum’s efforts to reconfigure itself in the next 50 years, Guidelli-Guidi says, ensuring that representation exists not only at the level of exhibitions but also in terms of building stewardship. Nengudi has created manuals for future reiterations, so that the installations can be faithfully reproduced. Their presence, and hers, will be lasting and permanent.

Senga Nengudi, Studio Performance with RSVP (1976), which features stretched nylon stockings, a recurring motif in the artist’s work

‘Senga Nengudi’ runs until spring 2025 at Dia Beacon, diaart.org

Nengudi’s solo show runs from 16 May – 28 July 2023 at Sprüth Magers New York, spruethmagers.com

This article was originally published in the April 2023 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today