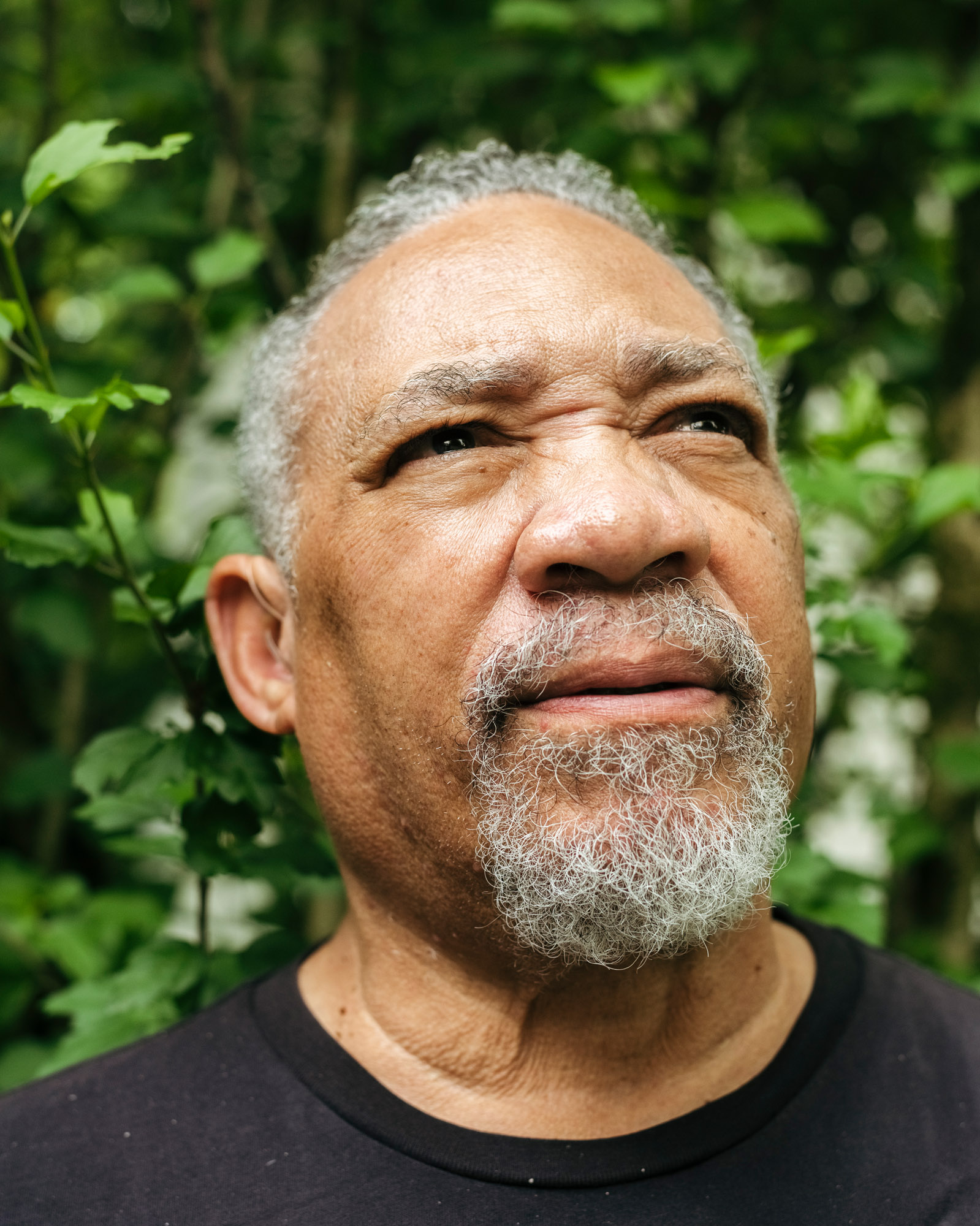

Jim McDowell, aka ‘the Black Potter’, on the fire behind his face jugs

A former coal miner, Jim McDowell defied the odds to set up his workshop and keep a historic form of American pottery alive

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Jim McDowell, who calls himself ‘the Black Potter’ – and features in the Wallpaper* USA 300 – has spent much of his 35-year-long career making face jugs, a form introduced by enslaved people of African origin in the US in the 19th century. But it took him until almost two years ago, aged 76, to finally get a gas- and wood-fired kiln of his own, despite a lifetime of pursuing what seems not to have been just a passion for pottery, but a calling.

Talking from his studio in Weaverville, North Carolina, McDowell says his family knew he was destined to work with clay from the time he was a toddler playing in a sandbox, and dates his awakening to attending a family funeral at the age of 13.

‘My grandfather told us that we had an ancestor named Evangeline who was a slave potter in Jamaica, and that she made face jugs. It struck a chord with me.’

McDowell’s workshop is packed with his memorabilia, including skydiving and archery trophies, and face jugs, a type of pottery first produced in the mid-1800s by enslaved Black potters in Edgefield, South Carolina. This line of smaller jugs is called Shortys, and most carry a message on the back

Like a lot of Southern folk traditions, face jugs came to the US via enslaved people, and they reflect their journey, combining elements of ancestor worship from West Africa, voodoo traditions picked up in the Caribbean, and the Christianity that people were forced to adopt in the US. Face jugs were originally created as a form of protection and to honour individuals; they were made deliberately ugly to ward away evil and were often used by Black Americans in place of tombstones, which they were not allowed because they were not considered to be fully human by the standards of white supremacy.

‘My face jugs are ugly because slavery was ugly,’ says McDowell. In the early 20th century, the form was appropriated by white craftspeople and took on racist overtones – a history the artist is determined to resist: ‘I’m taking it back, one jug at a time.’

Jim McDowell, Angel. McDowell often adds Christian symbols to his face jugs, and sometimes words from a gospel song or the oral folklore of enslaved people. The words on the back of this face jug are: ‘Fly Away. Be Free. BLM’

For McDowell, face jugs are vessels for the things that move him – ‘whatever shows the connectedness between humans’ – and for expressing the pain of slavery. Some of his jugs are dedicated to those he admires – Rosa Parks, Benjamin Banneker, even Ruth Bader Ginsburg – while others commemorate victims of racist violence, including Tyre Nichols, the 27-year-old skateboarder killed by police officers in Memphis in January 2023: ‘I kind of lost myself when I was making it. It looks like I took the anger I felt and channelled it into the jug. I can’t cuss people out; I can’t burn things down. It looks like a gargoyle because I have to use the anger,’ he said.

McDowell started his informal education as an army man stationed in Germany in the early 1970s, seeking out artisans in Nuremberg to teach him how to throw clay. ‘I went in and pantomimed that I wanted to learn the wheel. They said, “Nein.” They said that three times. And the third time, someone came out of the back room with a broom. I’m thinking, “Oh God, they’re prejudiced.” But I heard my father’s voice say, “You want to learn it, you’ll do it.” I swept the studio for three Saturdays in a row. And finally, they started teaching me how to do pottery.’

So began McDowell’s career as a potter, with all the challenges that entailed in the largely white world of ceramics. When he returned to the US, he used an entire paycheck earned as a coal miner to buy an electric kiln. Not being able to afford tuition at Alfred University – ‘the mecca of pottery’ as he calls it – McDowell studied with an Alfred graduate who used racial epithets freely. He put up with it because it was a chance to learn – and an opportunity to fire his pots in powerful, gas- and wood-fired kilns that could create effects he couldn’t achieve otherwise.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The process of tending to the fire requires vigilance. ‘It took two days to load the kiln, and five days to fire it. You have to know what to do, when to do it, and how to stay awake,’ he recalls. ‘I learned to take the shift no one else wanted, bring real, dried wood for the fire, and just make myself indispensable. And because of that, I got into all the wood fires. They’d say, “Yeah, bring Jim because he brings good stuff”,’ he laughs. ‘In exchange for the work, maybe I could get five or six pieces in. But look here, five or six pieces at the prices I’m getting now. That’s pretty good!’

A large pot and sample pieces of glazed pottery after having been test-fired in McDowell’s new kiln, in which wood ash flies around and adds coloration to the pieces

His work has begun to garner attention in the past few years, entering the collections of museums including the Nasher Museum and LACMA, as well as being showcased by Alex Tieghi-Walker’s craft platform Tiwa Select (which opened a New York space in 2022).

After a successful 2020 show at Connecticut’s Noyes House, McDowell began building his own kiln, which he calls ‘Sankofa’, a Ghanaian word meaning ‘looking into the past and pulling forward the stuff that helps us go forward’, explains McDowell. ‘Sankofa is in all my work now.’ This connection with history is what drives McDowell: ‘I am the bridge between the enslaved potters who worked on the plantation and made pottery there. When slavery was ended, they had nothing. Now I have just about everything that a potter could possibly have. And I’ve earned it on my own. But I’m on the backs of those people who came before me.’

A version of this article features in the August 2023 ‘Made in America’ issue of Wallpaper*, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today