Pedro Reyes: ‘sculpture is a very jealous goddess’

In ‘Tlali', an exhibition at Lisson Gallery, New York, Mexican artist Pedro Reyes carves into the spirituality of stone, the complex history of the American continent and the vocabulary of pre-Columbian and Mesoamerican civilisations

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Pedro Reyes’ latest body of work is all ancient history. It’s also searingly contemporary: old materials and methods as platforms for new socio-political critique.

His exhibition, ‘Tlali', now on show at Lisson Gallery, New York, mines the language and symbols of pre-Columbian and Mesoamerican civilisations. It also confronts the complexities within the United States of America and the larger continent it occupies; the land’s name originates from conquistador Amerigo Vespucci, responsible for the enslavement and death of countless indigenous communities.

Deriving from the Aztec language Nahuatl, the exhibition’s title, meaning ‘Earth’, refers to the deeply rooted and contested predicament of the continent’s given name. Reyes posits ‘Tlali' as an alternative, unblemished term for the continent, yet imbues the featured works with the political charge for which he is renowned.

Top: Pedro Reyes, Xochitl, 2021, white marble. Above: Coatl, 2021, volcanic stone. Photographer Daniel Kukla. © Pedro Reyes. Courtesy Lisson Gallery

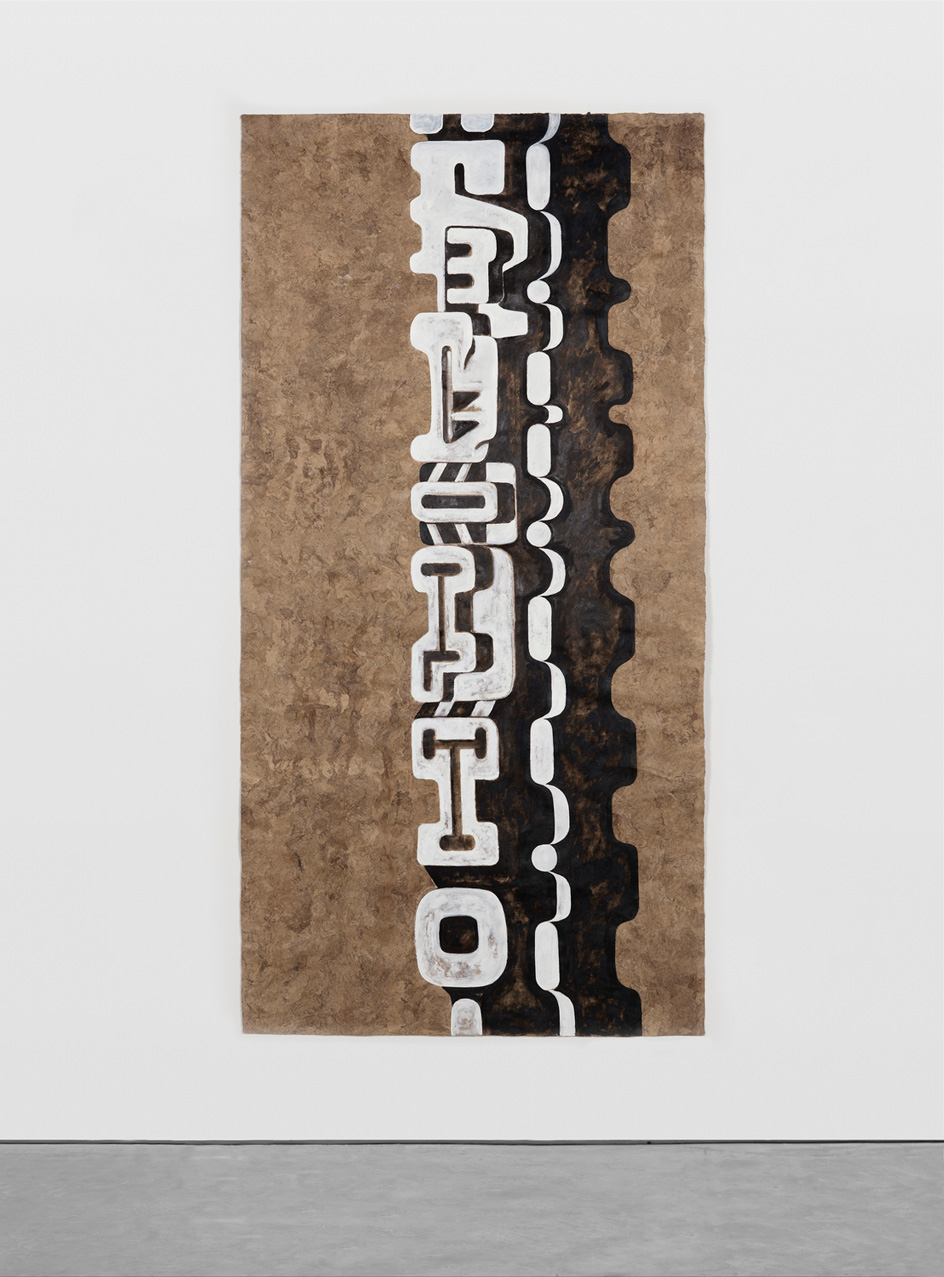

Reyes' show includes 14 carved, totemic stone sculptures alongside 11 drawings on handmade Mexican paper. This vast presentation engages with Mayan, Olmec, Toltec and Mexican heritage and serves as a reminder of the foundations of the American continent. These sculptures – rendered in volcanic stone, jadeite, and white marble – draw on the geometric vocabulary used to depict human figures and architectural models by Mesoamerican societies.

Coatl (snake), an imposing volcanic stone piece, resembles the weight and motion of a snake’s rattle. Reyes references the philosophy of balance and yin and yang. ‘The pieces are stacked in a rhythmic manner, rising to the top, and could continue endlessly.’

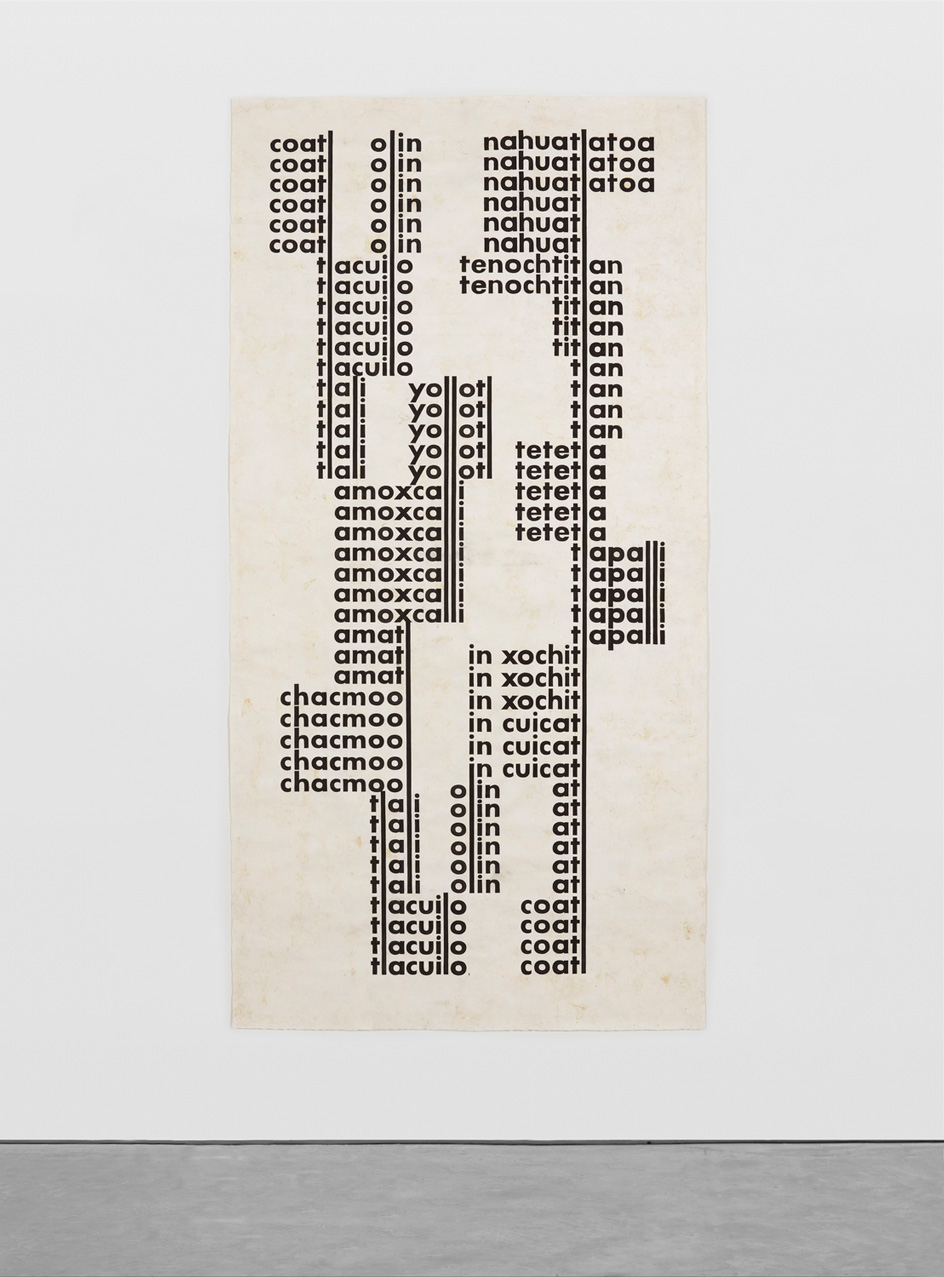

Top: Pedro Reyes, In cuicatl, 2021, amate paper. Above: Aztlán, 2021, amate paper

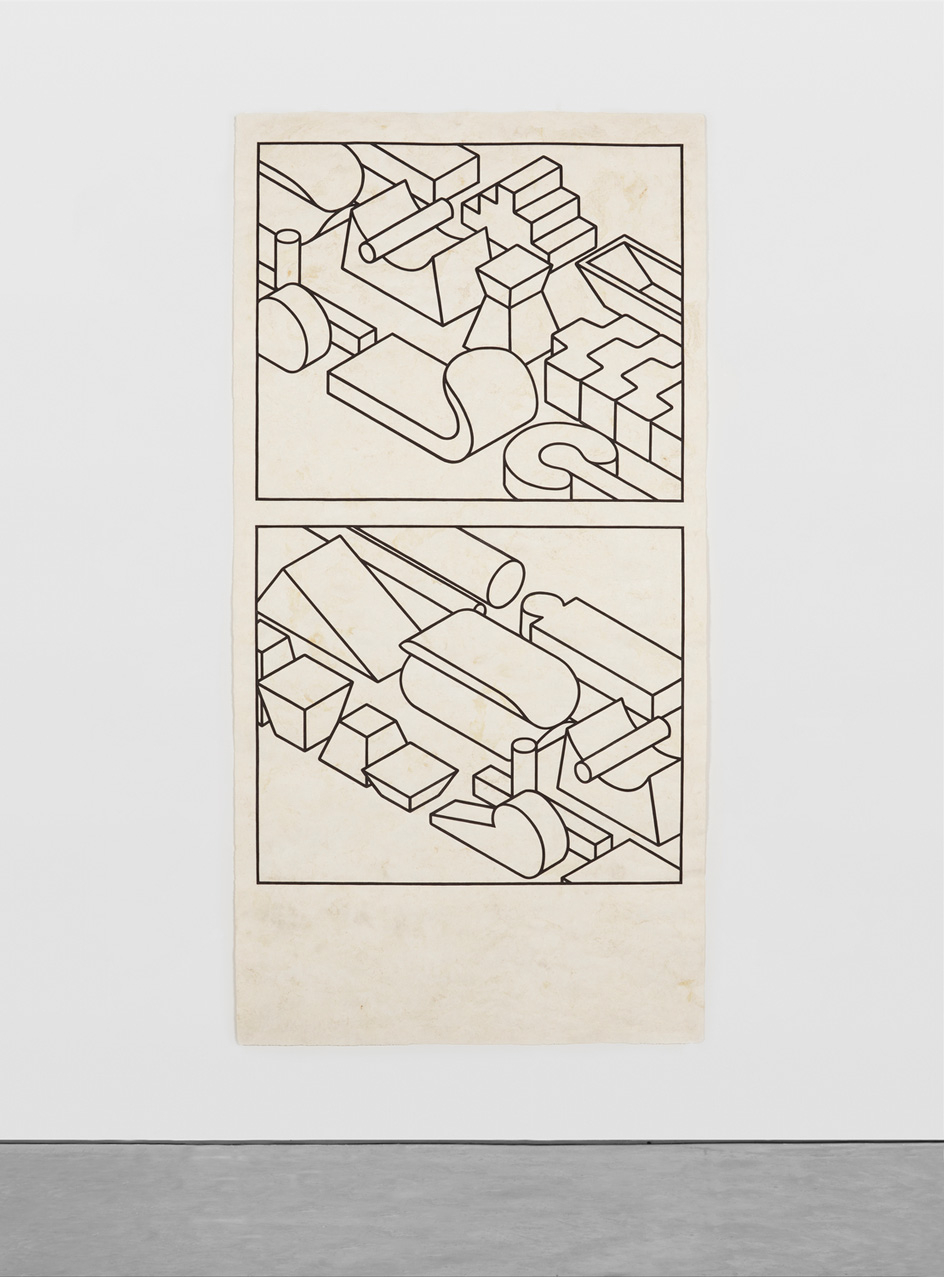

Elsewhere, the artist continues his dialogue with Mesoamerican typology on paper. These works, characteristically geometric, but in a very different mode, bear resemblance to political banners, serve as an index of language, symbols and patterns that echo pre-Columbian ethnology.

‘We do not know much about the poetry, dance, or music of the cultures that existed 4,000 years ago in Mexico. However, their sculptures are still here,’ says Reyes. ‘I am fascinated by the resilience of direct carving in stone. Once a stone has been carved, it earns its permanent place in the world. This power doesn’t necessarily have to do with scale. There are tiny artefacts that can feel monumental because of the intensity and concentrated care that they carry.’

Top: Pedro Reyes , Tonatiuh, 2021, volcanic stone. Above: Incuicatl, 2021 , white marble. © Pedro Reyes. Courtesy Lisson Gallery

For Reyes, the process of carving directly into stone is raw, spiritual, and respectful of the nuances in his material. Each stone that he collects from the local quarry is, as he puts it, already ‘halfway to a sculpture’, but the other half of the process is crucial: ‘I don’t believe in ready-mades. A lot of bad art has been made out of the idea of ready-mades, but there is something about rocks. Stones have an intrinsic sculptural value that asks for minimum intervention.’

RELATED STORY

A work of art gets better if you spend as much time as necessary with it. Sculpture is a very jealous goddess; she wants you to be there all the time.

Reyes lives in a self-built house with his wife, fashion designer Carla Fernández, in Coyoacán, in the south of Mexico City. Despite the global tumult of the last year, the pandemic has thrown up unexpected opportunities: ‘Not being able to travel was, in fact, beneficial because I got to spend more time in the studio,’ says Reyes. ‘A work of art gets better if you spend as much time as necessary with it. Sculpture is a very jealous goddess; she wants you to be there all the time. I have become a slave to sculpture.’ His exhibition was delayed for more than a year, but this afforded him a privilege of increasing scarcity in contemporary culture: slowness.

Top: Pedro Reyes, Ueueyeyeko, 2021, amate paper. Above: Tula, 2021, oil on amate paper. © Pedro Reyes. Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Reyes also took the time to engage with social practice – one of the key facets of his work – in a time of social distance. ‘I am very interested in finding ways to activate the aesthetic experience in the pandemic.’ he says. For a recent project, Tlacuilo (meaning ‘scribe’ in Nahuatl), he turned his personal library into a public library. ‘I have personally benefited tremendously from having access to libraries and want to promote and encourage people to continue to use them.’

Reyes’ work explores how individual and collective organisation can cultivate positive change. In one of his most notable participatory works, Palas por Pistolas (2008), the artist took aim at contemporary gun culture, working with local authorities in Culiacán, Mexico, to melt down guns into shovels, intended to plant trees in cities elsewhere in the world.

Reyes is an artist who believes in a deep engagement with his material. For him, creation is a physical battle and a spiritual encounter that requires ‘hundreds of decisions every minute’. It’s also a process that goes against one of the founding principles of conceptual art: severance of the artwork from its author.

‘I believe that, in the development of conceptual art, when one has an outsourced idea that is produced by other people, this has led to a lot of bad art,’ he says. ‘Art is a transmission of spiritual energy from the mind into matter and if this transition really happens you can feel it in the piece.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Top: Pedro Reyes, Acúfeno, 2021, blue calcite. Above: Cuauhcalli, 2021, oil on amate paper. Pedro Reyes. Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Pedro Reyes: 'Tlali', exhibition view. 504 West 24th Street, New York. Until 17 June 2021. © Pedro Reyes. Courtesy Lisson Gallery

INFORMATION

Pedro Reyes, ’Tlali’, until 17 June 2021, Lisson Gallery, New York. lissongallery.com

Pedro Reyes: ’Sanatorium’, until 20 August, MAAT – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, Lisbon. maat.pt

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.