Dream weaver: artist Liza Lou on the teamwork behind her beadwork

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

In the blue, even expanse above Los Angeles, clouds are rare – yet they have been a recent preoccupation for local artist Liza Lou. ‘If you’re someone who watches clouds, they happen here more often than you think,’ she says. They are the subject of her new solo exhibition, ‘The Classification and Nomenclature of Clouds’, inaugurating Lehmann Maupin’s second New York gallery on 6 September. The main event is The Clouds, 2015-18, a painting that, like Les Nuages from Monet’s Water Lilies series, is a monumental triptych that immerses the viewer in delicate tufts of colour.

Outside her studios in both Topanga Canyon and Durban, South Africa, Lou does as the Impressionists did: she paints clouds en plein air. But rather than using canvas, she paints on a grid of minuscule glass beads, threaded by hand by Zulu artisans based in South Africa. She dilutes her oil paints and layers them on in washes, or rubs them into the beads and wipes them away. Other times, she’ll apply thick swathes of impasto to the grids of beads, which retain the shape of the stroke of her knife. When the painted grids are dry, she takes a hammer to them, chiselling away at the beads and exposing the matrix of threads holding them together. It’s a way of adding depth and transparency, ‘a way of carving into a painting’, says Lou.

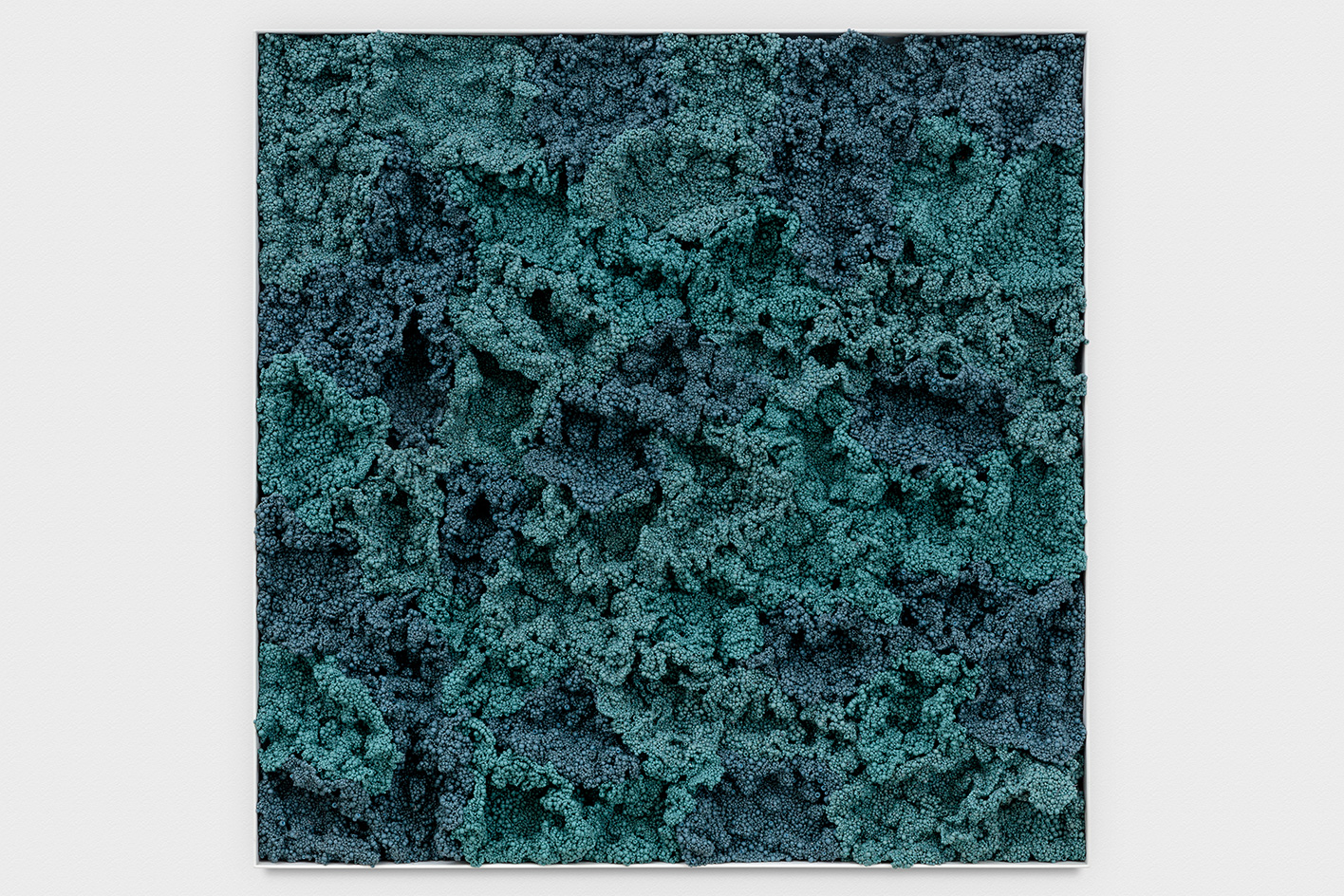

Lichenform II, 2018, by Liza Lou, woven glass beads. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul

Her body of work touches on the pointillism of Georges Seurat, pop art and geometric minimalism. At the heart of it all are the tiny glass beads, where the distinctions between painting and sculpture begin to blur. In arguably her most famous work, Kitchen, 1991-96, she covered a life-size kitchen with beads, down to the minutest details: the crinkles on the surface of a slouching potato chip bag, the water flowing from the tap. The transparency and reflection of millions of pieces of coloured glass created something of a luminous, three-dimensional Impressionist painting. Kitchen questioned the ideas of ‘women’s work’ just as the studded material challenged the distinction between ‘serious’ male art and women’s arts and crafts.

Lou was confronted with that prejudice early in her career. During her first days at the San Francisco Art Institute, she stumbled into a bead store and incorporated them into her paintings, a tactic wholeheartedly dismissed by her tutors. ‘It was decorative. It was too feminist,’ she recalls. After two months, she dropped out and began a career-long meditation on the division of sex and labour.

Kitchen took Lou five years and a few pairs of tweezers to complete. She estimates that each of the 600, 35cm square panels of beads that make up The Clouds would have taken her two weeks to produce. But Lou no longer works alone. In 2005, seeking to employ women with a greater mastery of beadwork, she travelled to South Africa, where Zulu women are renowned for their beading tradition. She hired an initial team of 12 to help her complete Security Fence, 2005, a razor-wire, chain-link enclosure with a crystalline sparkle.

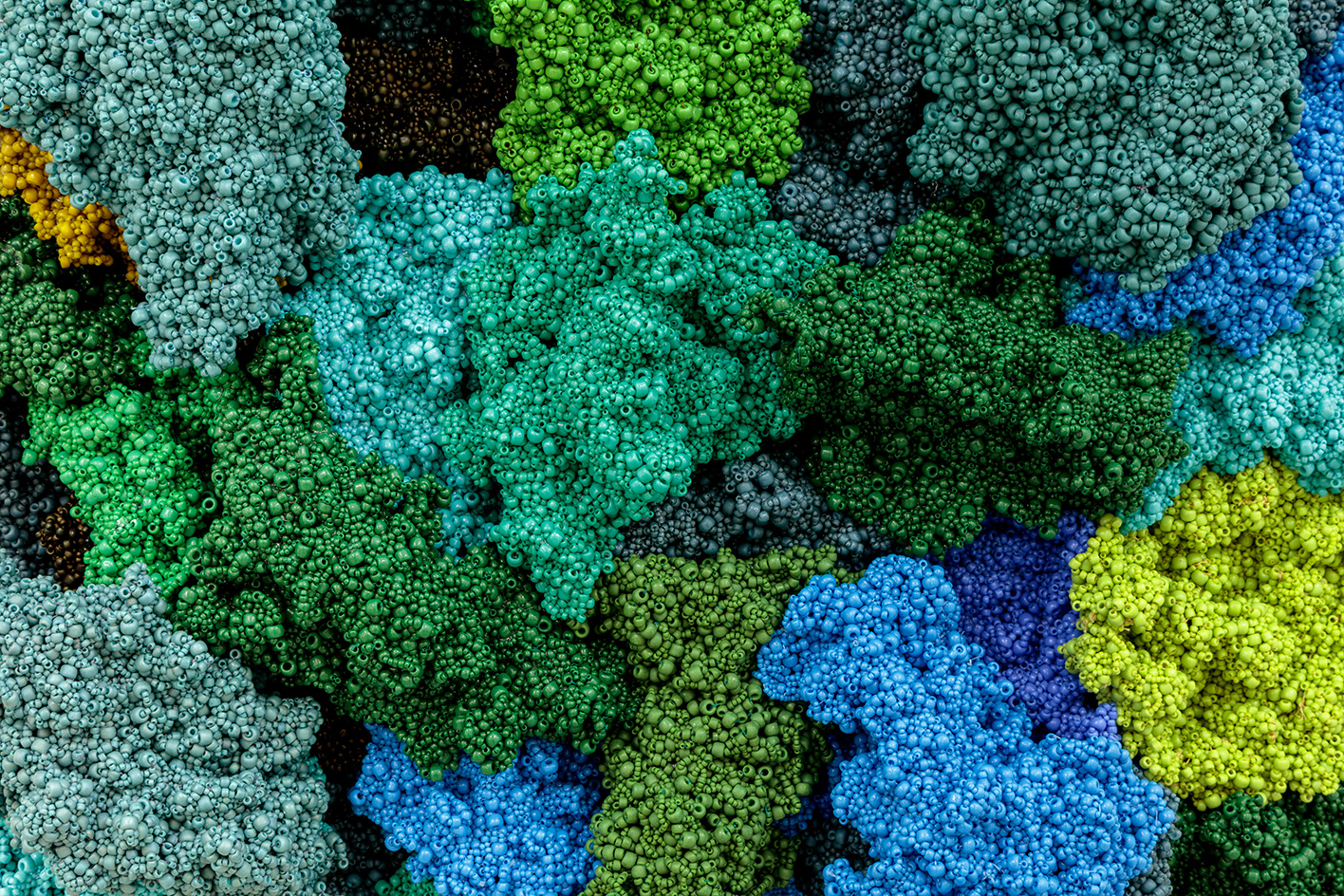

Lichenform I (detail), 2018, by Liza Lou, woven glass beads. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul

Having imagined she would leave after three months, Lou stayed in Durban for ten years. Living in South Africa triggered profound shifts in her practice, most visibly a move towards abstraction. Her Ixube series, from the Zulu word for ‘random’ or ‘mixture’, was a minimalist’s colour field. Treating her jars of coloured beads like paint, she would mix up varying hues, and disseminate batches among her team to be threaded. The resulting strips of colour made by many different hands were then woven into a single composition. Many of her team worked from home, so they could care for children; they would return their strips with the imprints of hands or smudges of dirt. These became so integral to the character of each piece that Lou eventually did away with colour entirely and made the imperfections the focal point of her work. Lou’s 2016 installation The Waves featured a thousand dishcloth-sized squares comprised entirely of white beads and the handprints of those that made them.

Emphasising process over concept, these new bodies of work revealed the shifts in Lou’s practice occurring at a deeper level. While Kitchen transformed the drudgery of domesticity into a glamorous wonderland, in South Africa the beads possessed weighty, centuries-old cultural significance. ‘The history of painting pales in comparison,’ Lou says. In Durban’s townships, women sold beaded works by the roadside. ‘It was lifeblood to them. Beads meant that if you could make something, you could survive.’

Living in South Africa galvanised Lou’s engagement with issues of women and labour into a kind of social practice. Acutely conscious not to aggrandise herself as a white saviour in Africa, she set the groundwork for her 30 employees’ economic empowerment with a sense of respect and humility, emphasising an ‘elbow-to-elbow’ dynamic in her studio.

Lou at work in her studio Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul

It was a break with local custom, however, when she required them to set up their own bank accounts rather than funnel their earnings into those of their partners. She also hosted Zulu speakers to destigmatise HIV and tuberculosis and facilitated medication; she created scholarships for her employees to attend business courses and university; and paid each of them enough to hire employees of their own.

‘I kind of went through a crisis coming home,’ says Lou, who returned to LA in 2015. The quiet hills of Topanga Canyon are a far cry from Durban’s ‘noise and joy and depth of encounter’. There, Lou started painting The Clouds, she says, a totally new direction for her work. ‘I was adjusting to being alone.’

Lou goes back to Durban intermittently. ‘I don’t promise myself I’ll always work with this material,’ she says. But the bond with her studio would outlast her use of beads, regardless: ‘The most beautiful people I’ve met in my life were in South Africa.’

The cloud patterns in Durban, too, Lou says, were incredible – stalwart puffs of white rolling across the sky. The occasionally wispy cirrus clouds and airplane contrails in LA are decidedly less impressive, though a reminder that she is never really alone. ‘There is something about the clouds that connects us,’ Lou says. ‘To everything, to everyone.’

As originally featured in the September 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*234)

Nacreous, 2018, by Liza Lou, oil paint on woven glass beads and thread on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul

Nacreous (detail), 2018, by Liza Lou, oil paint on woven glass beads and thread on canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul

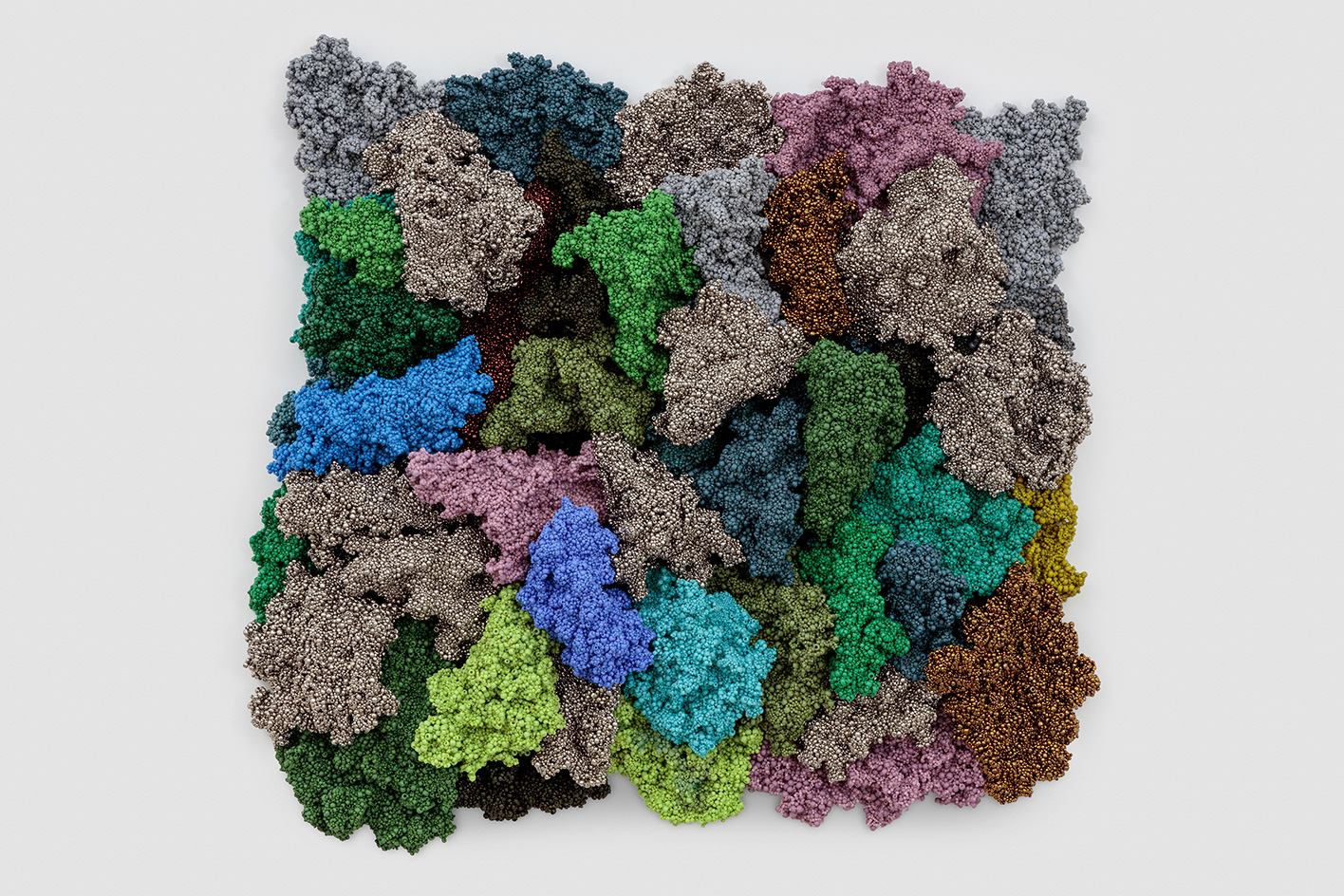

Aggregate: Mushroom, 2018, by Liza Lou, woven glass beads and thread. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul

Terra | Cloud, 2018, by Liza Lou, glass beads, thread, and epoxy resin on stainless steel. Courtesy of the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul

INFORMATION

‘The Classification and Nomenclature of Clouds’ is on view from 6 September – 27 October. For more information, visit Liza Lou’s website and the Lehmann Maupin website

ADDRESS

Lehmann Maupin

501 West 24th Street

New York

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.