Light house: James Turrell illuminates the Palladian masterpiece of Norfolk’s Houghton Hall

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

The American artist James Turrell owns 227 square miles of arid land near northern Arizona’s Painted Desert. He also owns almost 3,000 head of cattle, a few heavy European horses for pulling and lugging and, most significantly, an extinct volcano – the 600ft-high Roden Crater, into which he has been burrowing and punching holes for almost 40 years.

Turrell, who has been making art from light for almost half a century, is slowly crafting his volcano into an astonishing naked-eye observatory (W*139) – the most famous work-in-progress in the world. Michael Govan, director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, has called it ‘one of the most ambitious artworks ever created by a single human being’.

Houghton Hall, meanwhile, is a Palladian pile built on a manicured estate in the low lands of Norfolk, 20 miles from the North Sea coast. Originally constructed by Britain’s first prime minister Sir Robert Walpole in the 1720s, the house is now owned by David, seventh Marquess of Cholmondeley.

The difference between these two places, notes Turrell, is in the air. ‘England is at sea, and you really feel that’, he explains in the July 2015 edition of Wallpaper* (W*196). ‘There is so much moisture in the air. That softens the light.’ Light is different matter for Turrell than for most of us. It is his material.

Turrell has spent most of his life thinking about what light can do to buildings. ‘My father was a pilot,’ he says. ‘We were flying in the desert near Las Vegas. You could see Santa Monica in the distance and it was changing to the night-time environment. We were just staring at it for the hour and 20 minutes of that flight. And my father said, “a peasant by day, a princess by night”. That raiment of light on things can change buildings dramatically from day to night.'

Houghton Hall is no architectural peasant, but this experience and insight informs what Turrell is doing here. ‘You can take the architecture apart and put it all back together again with one quality or colour of light. And that is what I am doing with the building.’ Turrell describes this deconstruction as close to music, and the creative process something like sensory synaesthesia. ‘It is like variations on a theme. I bring it together, then I dissect, then I bring it back together; and then do it again and bring it back together, but in a slightly different way from the first time.’

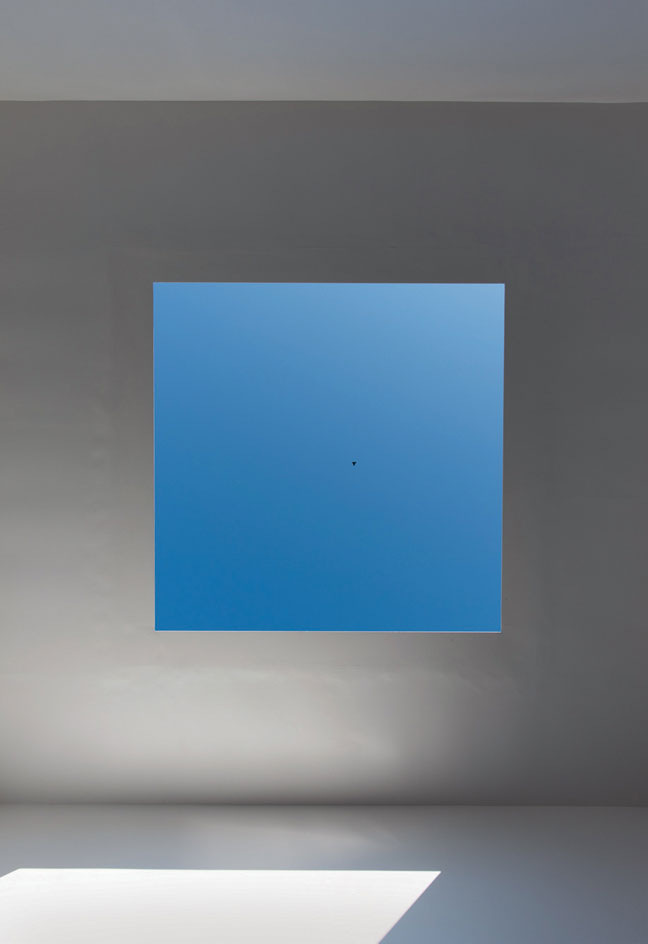

He has already made a permanent impact on the house, in the Skyspace that Cholmondeley asked Turrell to design for the property. An elevated oak box, big enough to seat 20 people, Seldom Seen rises into the trees of an enclosed copse. Visitors sit here at dusk or dawn to watch the Norfolk sky cycle through blues and purples and fill with stars. Opened in 2004, it was the site’s first contemporary art installation.

This summer, a number of Turrell’s pieces – including projections, holograms and brass models of the spaces he has created at Roden Crater – will be on display at the house, but the centrepiece will remain his illumination. The 45-minute-long spectacle will run from dusk every Friday and Saturday until October. ‘I think twilight is what we were made for,’ he says.

But Turrell has no interest in light as metaphor. ‘I’m interested in the experience of light,’ he says. ‘I don’t want something that depicts light, but light itself.’

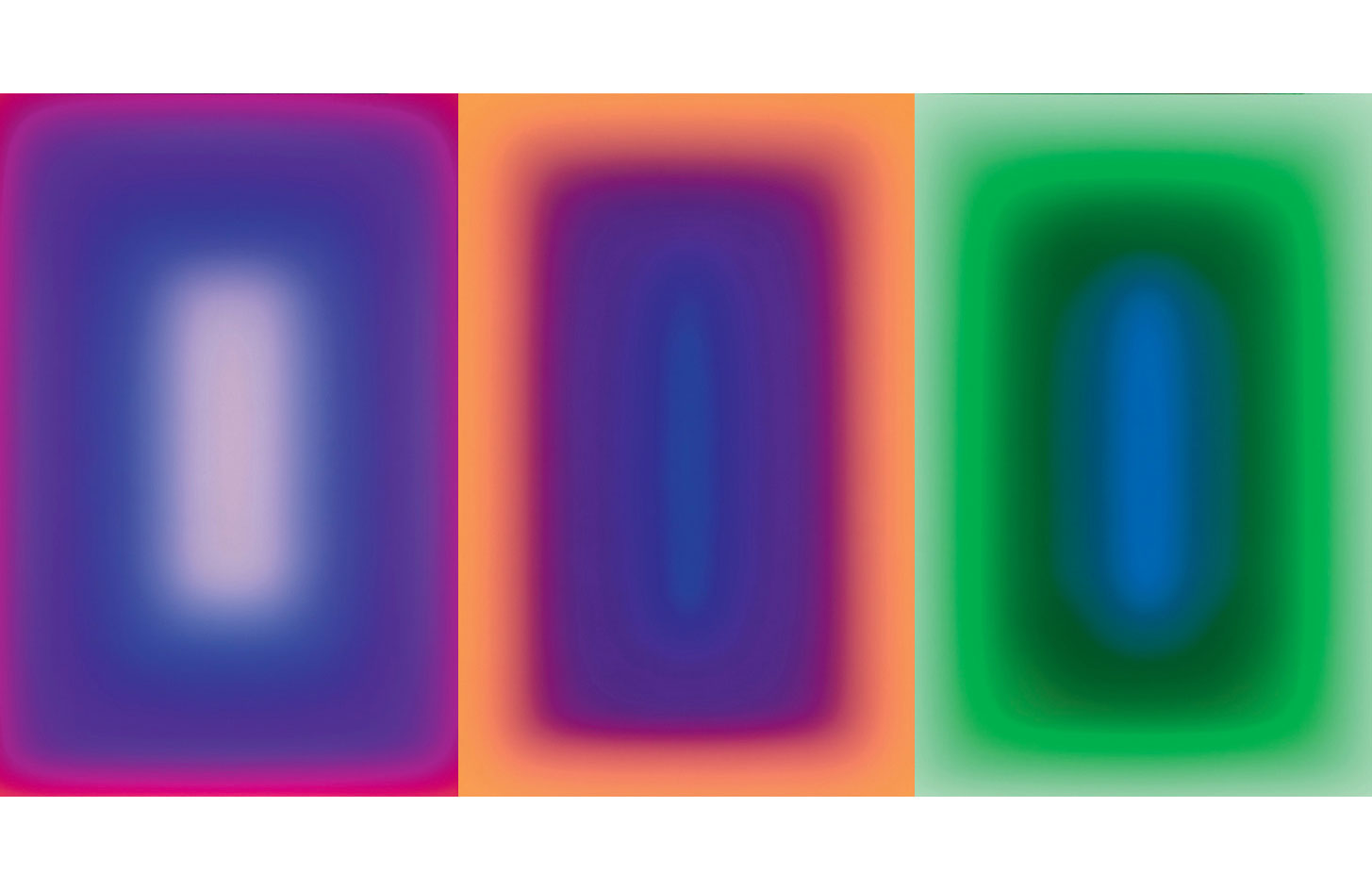

In 1967 he rented an old hotel, the Mendota in Santa Monica. He covered the windows and began experimenting with natural and artificial light, using projectors to create what looked like solid objects. He also began to punch holes into the hotel’s walls and ceilings to frame the sky, working out ways to remove the unfathomable distance. He then shone different coloured light at these holes and changed the colour of the sky – or at least the way we understand the colour. Turrell wanted to make clear that the way we perceived light and colour was not fixed and constant. Out of these experiments, he developed particular forms and devices, long running series of variations on a theme: not only the Projection Pieces and Skyspaces but also Wedgeworks – floating planes of light magicked up in darkened rooms – and Dark Spaces, where it might take 30 minutes to detect a coloured fog.

As much as it irks him, Turrell is often seen as an engineer of the transcendental (and an exacting one at that: his works require the creation of specific spaces, walls and incisions, with tolerances of 1/64th of an inch). But other works offer disequilibrium: his Ganzfeld rooms, drenched in colour, are designed to recreate the effect of a white-out, a total loss of bearings. During a show at the Whitney Museum in 1980, a few visitors got so disoriented they fell over (two of them even sued the museum and artist). His Perceptual Cells, meanwhile, require the viewer to enter a sphere filled with light so intense that even with your eyes closed, you start to see strange shapes.

In 1974 the owner of the Mendota Hotel threw Turrell out. He had learned to pilot a plane as a teenager, and for seven months he flew across the Western skies, sleeping on a bedroll under the wings at night. He was looking for something.

He found it in Roden Crater. A few years later, Turrell secured the finances to buy the volcano, taking the surrounding ranch land as part of the deal and initiating the complex business of raising funds to start his work. Forty years later, he is nowhere near done.

According to the few who have been granted visiting rights to Roden Crater, what is there is remarkable: chambers and monoliths, shafts calibrated to the summer solstice or a particular lunar positioning that occurs once every 18.6 years; one 845 ft-long, 12 ft-wide tunnel has been tuned like a flute with the assistance of an acoustic engineer.

Turrell’s attention to detail, and the quality of finish, materials and effect of his work is legend. But that kind of practice is time-consuming and expensive, and Turrell is way off schedule. He is under pressure to open the finished parts of Roden Crater to the paying public to help fund the rest of the work. But he’s reluctant. ‘It’s like a painting,’ he says. ‘I want to finish it before I put it on display.’

Of course, you don’t have to get an invite to the Arizona desert to see Turrell’s work. There are Turrell pieces all over the world. Over the last decade, with the reputation of Roden Crater growing, he has become one of American art’s grand old men. The critical embrace has come late, but Turrell can live with that.

‘I sure would have liked this attention and the offers 30 years ago when I wouldn’t have been so strung out by jetlag,’ he concludes. ‘But I’ll do it now, that’s OK.’

For the unabridged version turn to page 082 of W*196

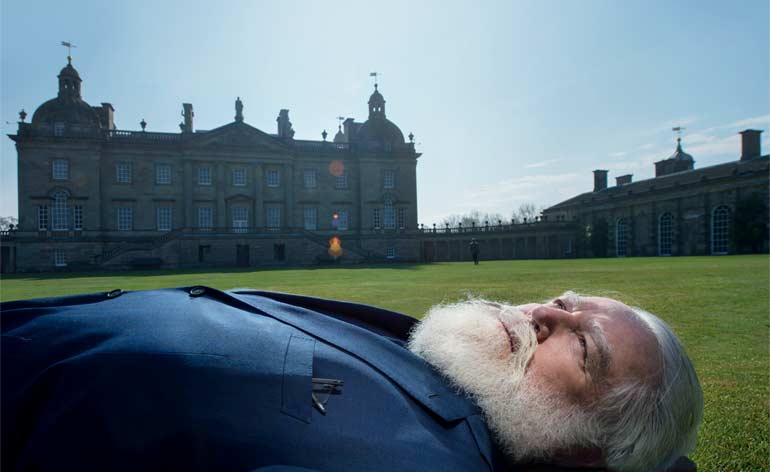

American artist Turrell makes use of light – his favoured medium – to illuminate the west facade of Houghton Hall, a spectacle held at dusk and running in 45-minute cycles.

This latest installation lights up the castle in multiple colours, embracing the palpable and the intangible.

‘I don’t want something that depicts light, but light itself,' says the artist.

Turrell's career has always revolved around the exploration and exploitation of light's capacities.

Turrell's 2004 Seldom Seen Skyspace allows visitors to look at the Norfolk sky through a square opening.

One of Turrell's 'Tall Glass' series, 2015, which use banks of tablet computers behind frosted glass.

ADDRESS

Houghton Hall

King's Lynn

Norfolk PE31 6UE

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.