Generative art: the creatives powering the AI art boom

It’s a new age for generative art, thanks to pixel-sorting, algorithm-sifting creatives. While the NFT market remains in flux, we delve into the rise of generative art, and the AI art boom

Generative art is defined by the unseen hand – a system or algorithm or AI-powered design program that, working with variables and within parameters established by the artist, can generate almost infinite outcomes. And for some, it’s the future. ‘The most radical and interesting art is happening in the generative art space,’ argues the Irish artist John Gerrard. ‘It’s the work most aligned with contemporary conditions.’

Gerrard is not yet 50, but he’s been tagged as an OG of generative art, a title he’s not entirely comfortable with. Most of his work – the mesmerising Farm and Solar Reserve, for instance – is produced using game engines, though it is not classically generative. But he is evangelical about the potential of generative art and the wave of younger artists redefining it. German artist Kim Asendorf is a particular favourite. ‘He’s a coder and an artist who invented a process called “pixel sorting”,’ Gerrard explains. ‘He’s creating a new language of abstraction, which is only going to get more interesting over time. Give me this over any painting of the last 15 years.’

Solar Reserve (2014), by John Gerrard

Full disclosure, Gerrard is an Asendorf collector. But as of right now, and for a relatively modest outlay, you could be, too. Asendorf’s artworks are minted as NFTs and available on the fxhash generative art platform for as little as two Tezos, equivalent to about $2. Gerrard has now created his own series of categorically generative art pieces, Bone Work, for the platform.

Over the last couple of years, fxhash and the more blue-chip Art Blocks have emerged as the key platforms for generative art NFTs. And for Gerrard, alongside others, they are leading the revolution. ‘I put the blockchain mechanism, as a new distribution and exhibition model, up there with photography in terms of what it is going to do,’ he says. ‘I think it’s transformative.’

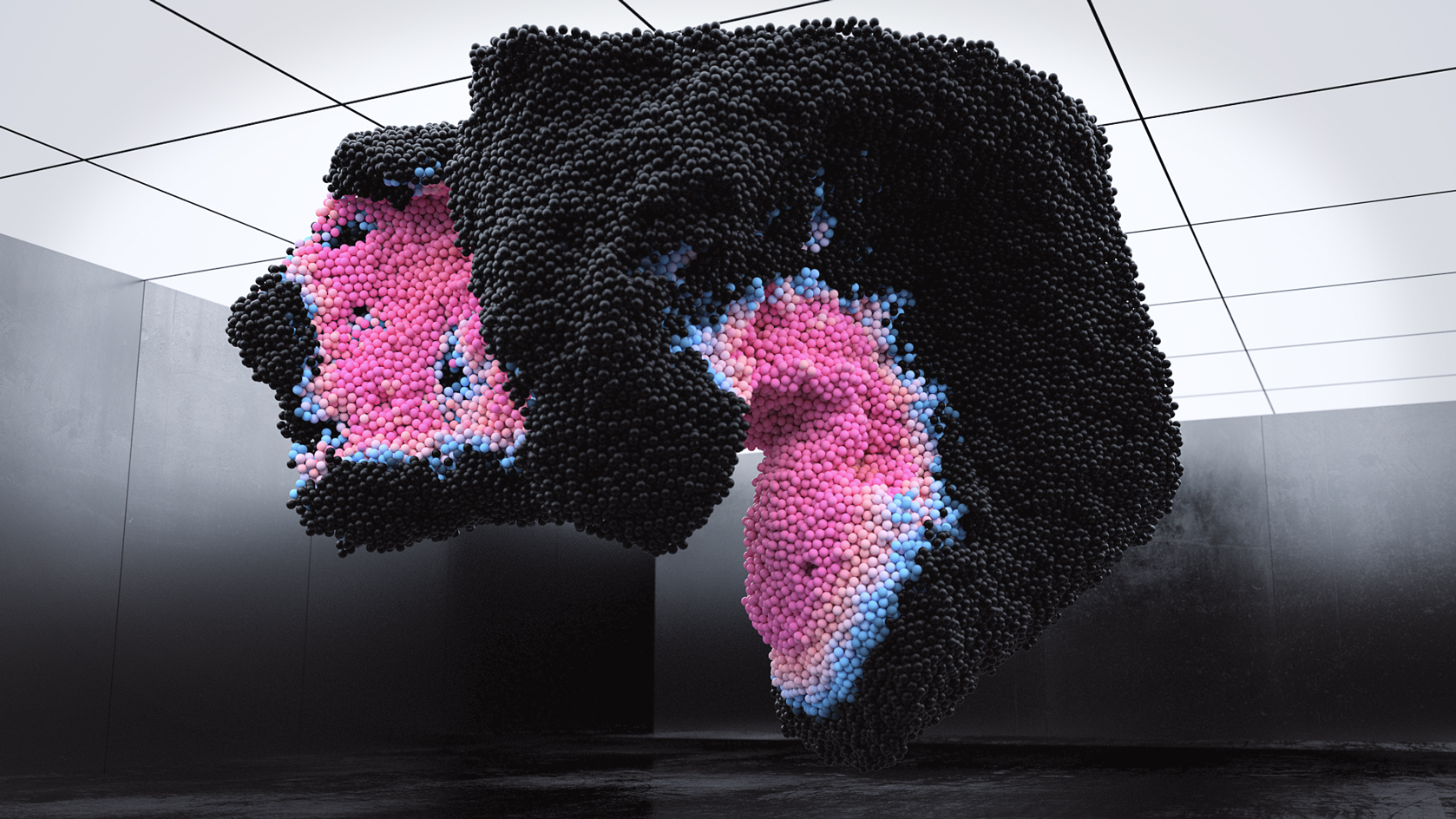

Maxim Zhestkov, Volumes, 2018

Of course, there was generative art before the blockchain. Many trace its roots back to the procedural art of Sol LeWitt and the ‘arranged by chance’ work of Ellsworth Kelly, while the Hungarian artist Vera Molnár gets credit for pioneering computer-generated art in the late 1960s. The English artist Keith Tyson (W*212) created the ‘Art Machine’ in the early 1990s, using algorithms to randomly generate words and ideas he could turn into physical art, and the American artist Casey Reas, who co-created the open-source programming language Processing, has been producing what Gerrard calls ‘long-form’ generative art for over two decades.

Over the last decade or so, collectives such as teamLab, Universal Everything and a’strict, and artists Jakob Kudsk Steensen (W*268), Refik Anadol and Maxim Zhestkov, have used increasingly sophisticated programs to magic up fabulous, immersive digital landscapes and projections in physical spaces, setting in motion an evolution of alternative digital worlds and lifeforms.

The Berlin-based art foundation Light Art Space (LAS), in particular, has become a showcase for large-scale immersive digital art. Launched in 2019, it debuted with a Refik Anadol installation and has since shown work by Kudsk Steensen and Libby Heaney (W*276), who brings the confounding magic of quantum computing to generative art.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘We want to show what is relevant now, but even more so, what will define the next 20 or 50 years,’ says LAS director Bettina Kames. ‘Platforming the latest technologies as an artistic medium is central to that approach; we’re here to bridge the gap between society and these technologies.’ LAS recently presented Ian Cheng’s Life After BOB: The Chalice Study (W*283), which features the longest and most complex animated film ever generated in the Unity gaming engine.

Ian Cheng: Life After BOB, 9 September - 6 November 2022 at Halle am Berghain, Berlin

The Asendorf strain of generative art is more scrappy, lo-fi and explicitly algorithmic, and also oddly painterly. Take the almost-op art of Tyler Hobbs, Dmitri Cherniak’s whirring tape heads, Anna Ridler’s art of the data set, the shape-shifting work of Itzel Yard (aka IX Shells), the psychedelic landscapes and portraits of Ellie Pritts, the reconfigured myths of Morehshin Allahyari and the mixed-media collages of Juan Covelli. This wing of generative art mostly runs on small screens rather than in large spaces, and heralds a post-speculative bubble era of NFT art, built around genuine innovation rather than hype and drop-culture economics.

Originally, most galleries and art fairs gave generative art a wide berth – to deadening effect, argues Gerrard. ‘Collectors and galleries have been successful in largely keeping out the digital, but, in doing that, they have kept out contemporary conditions. If you go to an art fair now, it’s like travelling back to 1960, nothing has changed. That’s dangerous for art, artists and collectors because it’s a very conservative environment.’ Generative art’s embrace of NFTs, he says, was largely a case of having nowhere else to go. ‘The art world had no room for an artist like Asendorf. So in a way, digital art has made its own room through the digital platform. And it’s exploding before our eyes.’

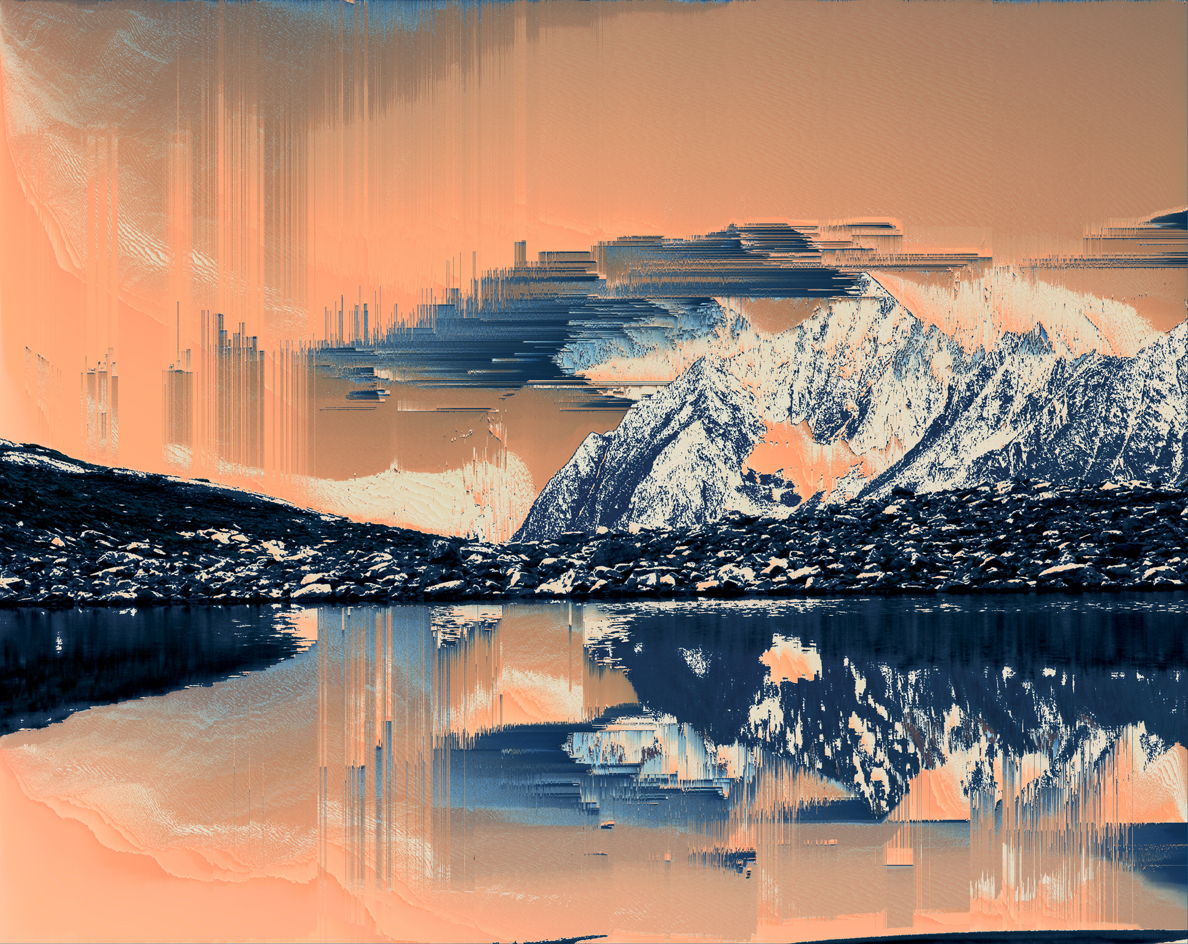

Mnot Abcln B, 2010, by Kim Asendorf

Hobbs and Yard, in particular, are blowing up price-wise. Last year, a single Hobbs NFT sold for $3.3m, while the rights to mine 99 new NFTs sold for $17m. A single Yard/IX Shells NFT sold for $2m. Unsurprisingly, the big galleries are now involved in a clamorous if still uncertain rush to join the party. Pace can rightly claim to be ahead of the pack. It launched Pace Verso in 2021 with a mission to put digital and Web3 tools in the hands of its artists. And last year, it announced a partnership with Art Blocks, which launched with Gerrard’s new NFT series Petro National.

Ariel Hudes, who heads Pace Verso, is the first to admit the initial speculative hype around NFTs, and the bad art that drove much of it, was also a deterrent to other galleries. She also argues that a very sharp popping of that speculative bubble is a long-term positive in terms of the quality of generative art produced. For Hudes, the job is now to put the tools of generative art into the hands of artists, and expose the wider Pace collector base to generative art (and hold their hands while navigating the complex crypto-mechanics of actually buying NFTs) – as well as hopefully introduce the very distinct Art Blocks collector to collecting physical art. ‘I think NFTs have created a new wave of people who are excited about art, and want to talk about art,’ Hudes says.

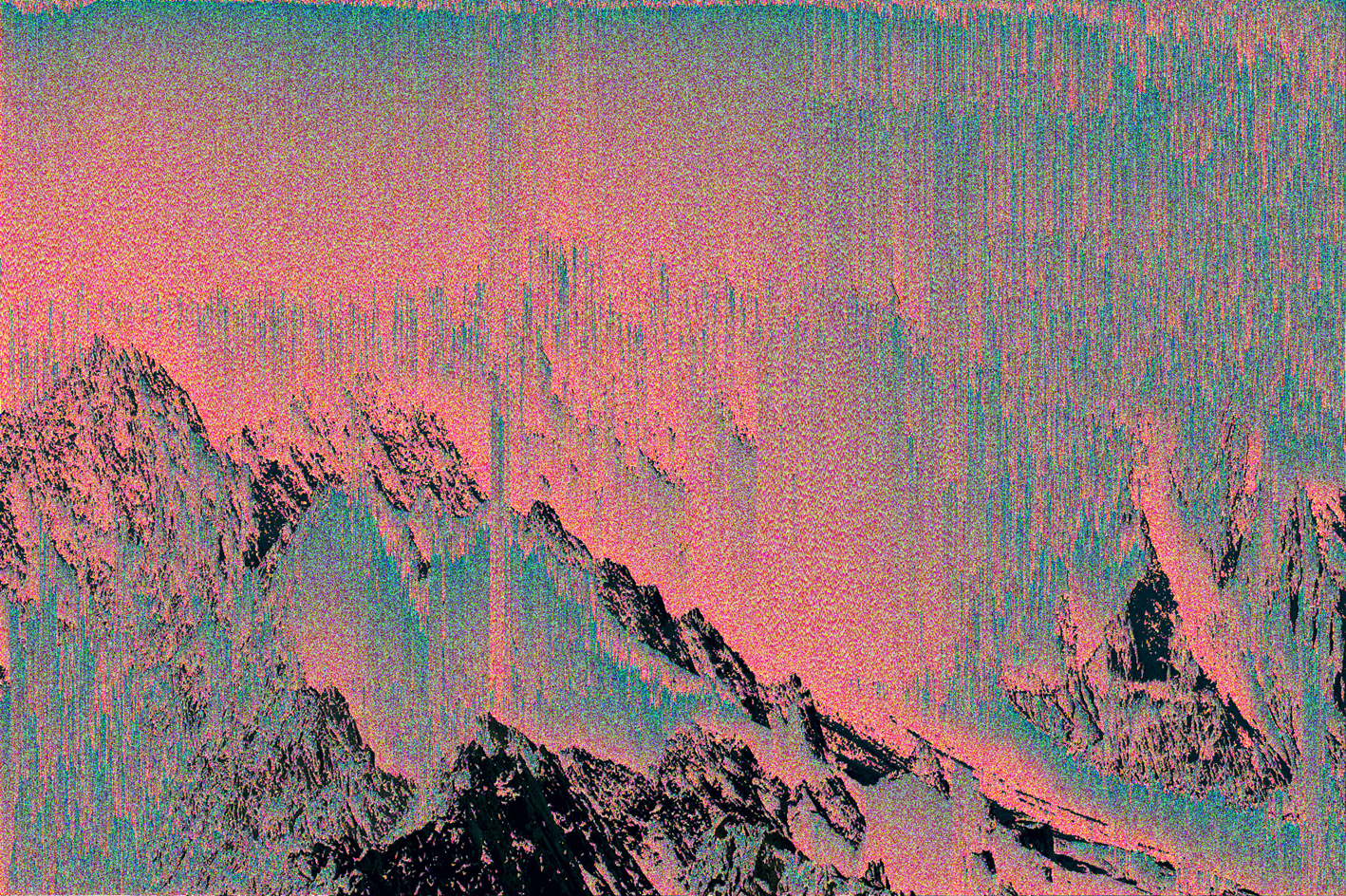

Fidenza #527 (2021), by Tyler Hobbs

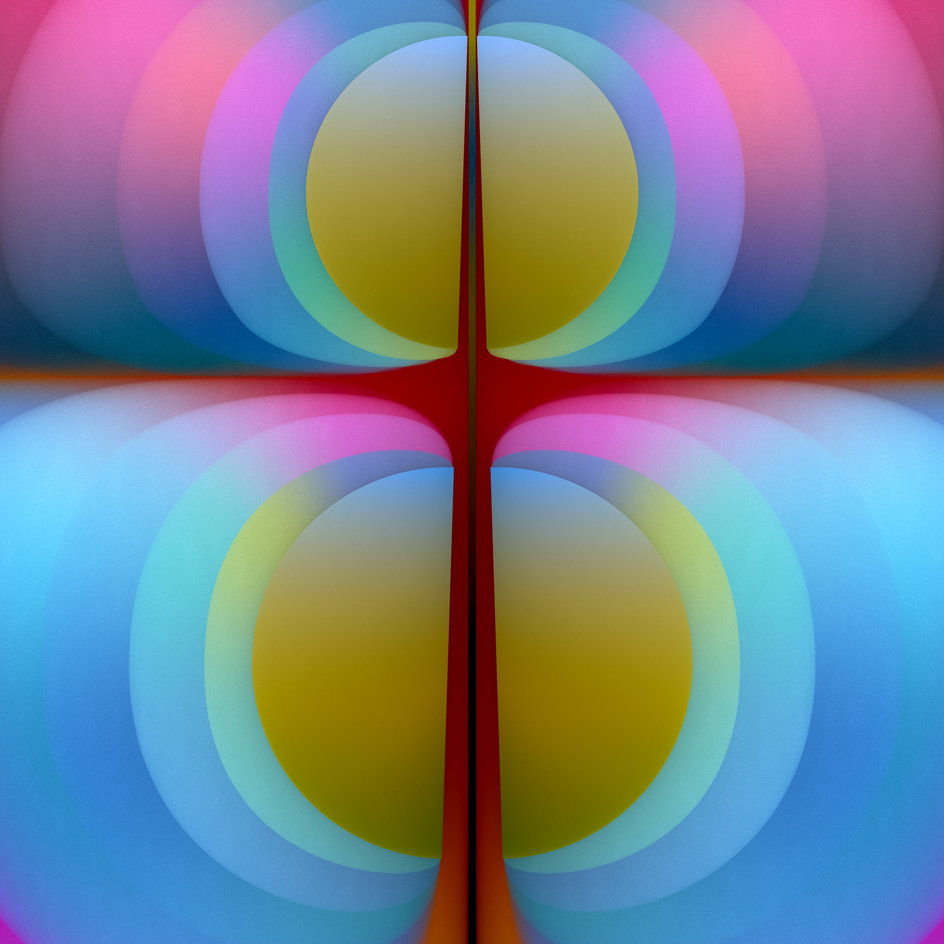

One of Hudes’ projects is the launch of NFTs by the painter Loie Hollowell. The series, Contractions, is based on Hollowell’s Split Orb paintings, a typically lush, semi-abstract meditation on childbirth. Hollowell and Pace Verso let an algorithm work on various elements of the original pieces to create 280 unique, generative NFTs. Hollowell, who describes herself as a luddite, says the NFT-generating creative process was ‘organic’. ‘There were these spontaneous forms that I use in my practice that I had no intention of producing within the NFT,’ she says, ‘but they presented themselves nonetheless.’

For Hudes and Gerrard, generative art works best when the artist has tight control of the variables in play and a clear vision. ‘To me, some of the most technically complex pieces are the least interesting,’ says Hudes. ‘You see video game-type renderings of these dystopian worlds and they look amazing. But it doesn’t make it good art. You have to prioritise the artist’s eye over the computer.’

Contraction #166 (2022), by Loie Hollowell

Kames takes a slightly different tack. ‘Artists are often the first to experiment with new technologies,’ she says. ‘Take Jakob Kudsk Steensen’s Berl-Berl virtual swamp, for which he created a completely new visual language in a game engine.’

For Gerrard, the key is actually the democratisation and greater accessibility of these digital tools. He is particularly excited about WebGL, a browser-based 2D and 3D design program. ‘It’s an emergent culture,’ he argues. ‘And you are going to get different forms of complexity emerging – spatial, temporal and conceptual complexity. It’s really all just getting started.’

A version of this article appears in the January 2023 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Read more about Artificial Intelligence and the future of the creative professions