Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

On the day of our video call, Jakob Kudsk Steensen is in the midst of an expedition in the Spreewald Biosphere Reserve, a wetland area in the German state of Brandenburg. It is teeming with life and removed from civilisation (he’s had to drive to a nearby small town to get reception). He and his team are at the reserve for a few weeks to study the landscape, paddling around in canoes and wielding underwater cameras, microphones and hydrophones ‘to document all this life that lives between the soil and the forest’.

The work is methodological and meticulous – perhaps de rigueur for an environmental biologist, but highly unusual for an artist. Of course, many artists go to great lengths to acquire insight into their subject. But few have made extensive fieldwork such an integral part of their practice, and fewer still have done so in the service of digital art.

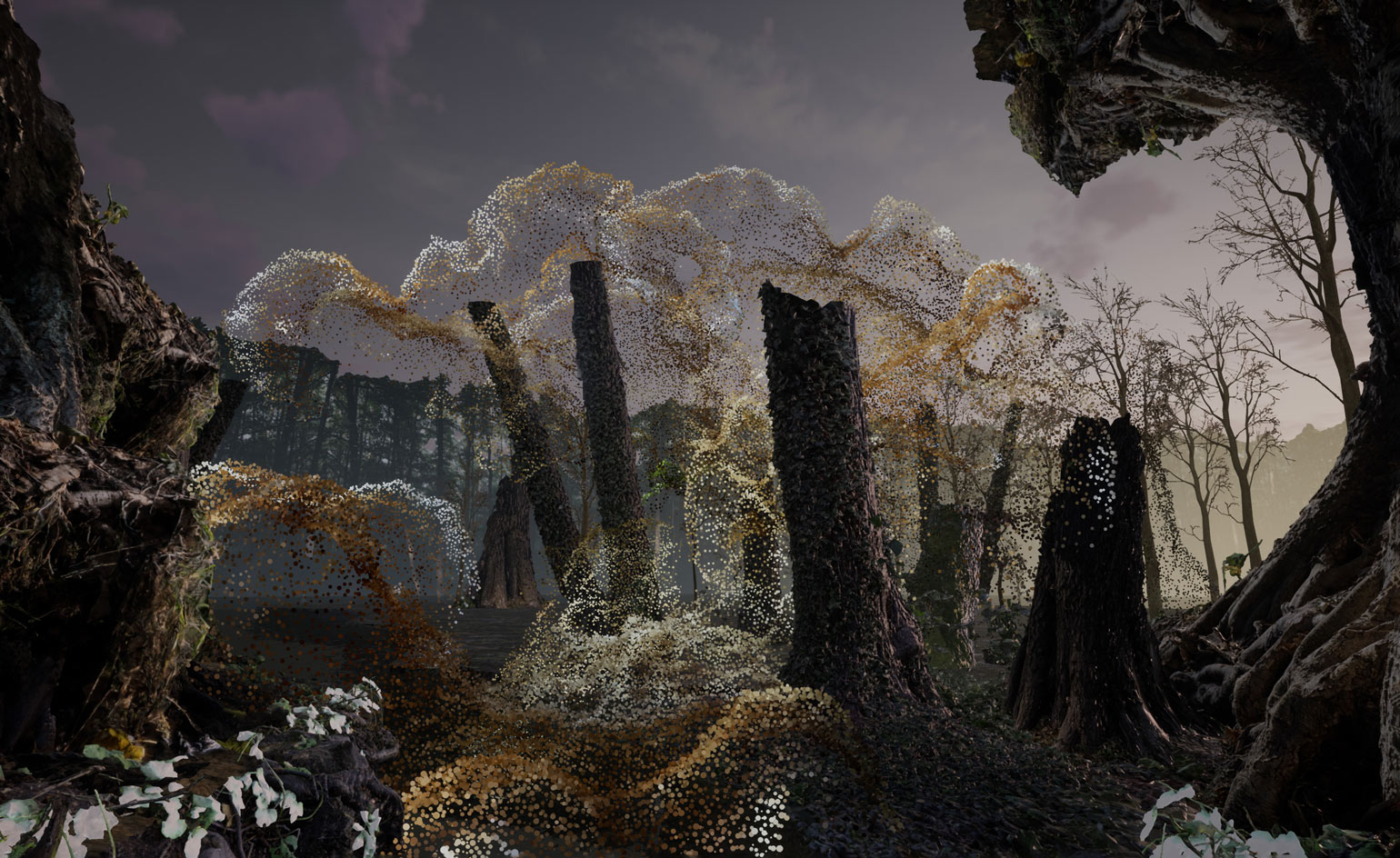

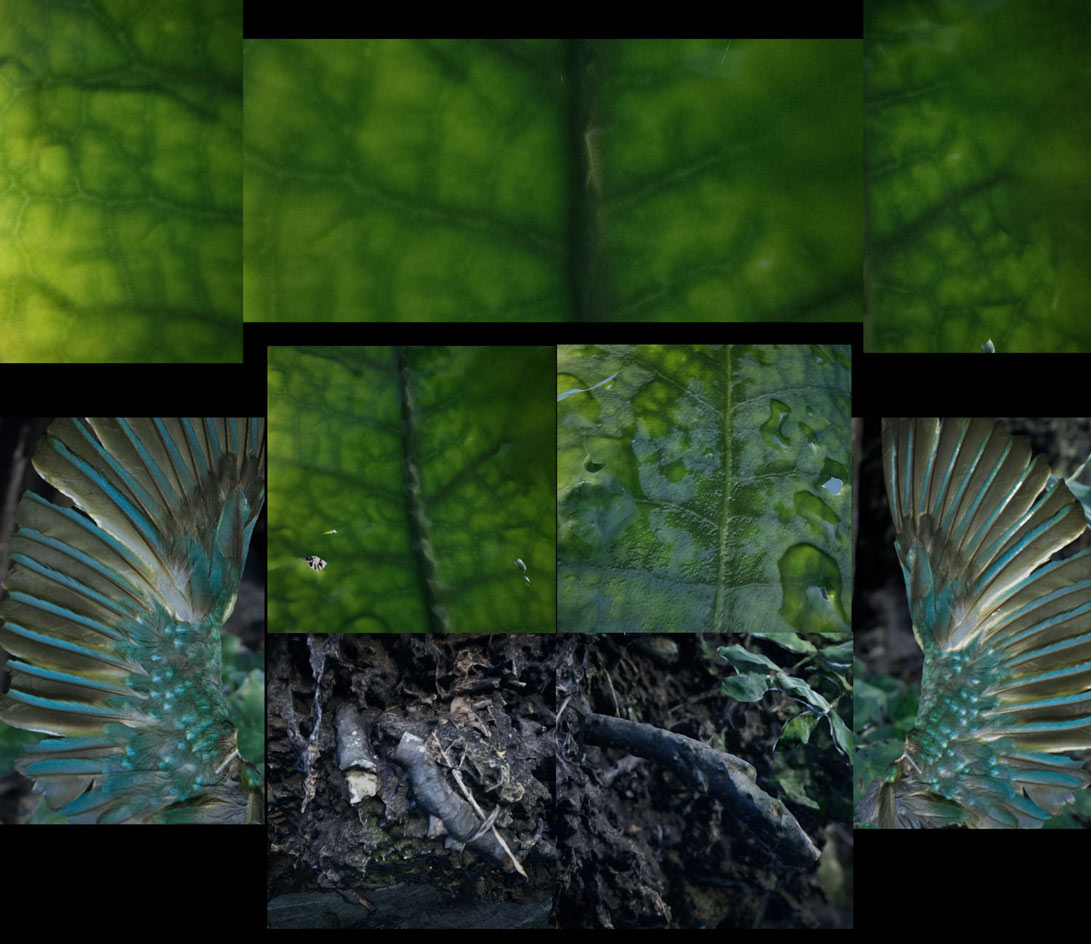

Berl-Berl alternates between majestic views of Jakob Kudsk Steensen’s virtual wetland and close-ups of 3D-scanned natural elements

‘I like to dive as deep as I can in my craft,’ explains Kudsk Steensen. ‘To create digital textures the way I do for a rock, I need to take 200 photos just of that rock, look at them, analyse them, and modify them.’ This immersive approach to art-making began with A Cartography of Fantasia (2015), a video installation for which Kudsk Steensen spent two months driving around Murcia to document the afterlife of Spain’s deserted resorts, the legacy of reckless financial speculation. ‘When you move through an environment, you start perceiving movement, time and scale in new ways. And because you’re experiencing it in new ways, you also start imagining new kinds of emotions or landscapes or places in your head,’ he says.

He describes his process as a reaction to the boom of ‘post-internet art’, the collage-driven works created at breakneck speed for an era of short attention spans and infinite scroll. ‘Around 2015, digital art was becoming this very fast, very commercial field. I just couldn’t connect to that.

I decided very intentionally to make my work as human, as emotional and as sensory as I could.

This awakening led him to spend a year creating a virtual island for Primal Tourism (2016), modelled on Bora Bora, a popular tourist destination in French Polynesia. His version features abandoned, futuristic architecture amid a primordial landscape. He spared no effort in researching the project, collating satellite maps, tourist photographs, scientific illustrations and drawings from the logbook of Jacob Roggeveen, an 18th-century explorer. Kudsk Steensen rendered the leafy island in dazzling detail, and programmed camera movements so viewers could explore it from the perspective of humans, animals and drones. Beyond its escapist appeal, Primal Tourism tapped into wider conversations around climate change, and the fraught relationship between colonialism and tourism. It set the bar high for virtual reality art and continues to be shown today. Just this March, Serpentine Galleries organised a live multiplayer event on the island, hosted by Kudsk Steensen and three of his collaborators.

While the themes of Primal Tourism reflect more contemporary concerns, its building blocks – a love of nature and a fluency in gaming technology – can be traced back to Kudsk Steensen’s upbringing. As a child, he attended a Steiner kindergarten, which emphasised outdoor learning and play; his family had a fondness for natural landscapes and taught him about plant and mushroom species. When he was nine, they moved to Nørre Nissum, a rural town in western Jutland with a population of around 1,000. ‘At the same time, video games really exploded,’ recalls the artist. ‘My friends and I suddenly had access to these extremely expansive, open virtual landscapes within three-dimensional video games where you could really navigate space. And it just absolutely captured our imaginations and became a huge part of our lives.’

Rendered in meticulous detail across screens of varying dimensions, Kudsk Steensen’s virtual wetland emphasises textures, tactility and a slow sensibility, qualities that have so far been rare in VR art

He can still describe in vivid detail his favourite virtual landscape from that time, a multiplayer map called Facing Worlds from the 1999 first-person shooter game Unreal Tournament. The map shows two islands on opposing ends of an asteroid, each with a pyramid-shaped tower reminiscent of a Meso-American temple, while the Earth looms in and out of view in the background like a majestic blue marble. ‘Now it looks like square blocks, but at the time it was considered hyper-real, and had this strange effect of connecting you to something new and virtual,’ he enthuses. Facing Worlds captivated the young Kudsk Steensen and inspired him to learn the tools that would allow him to modify these in-game worlds. So much so that he set his sights on becoming an animator, only to change course when, at his first animation test, he was asked to draw the same character 17 times. ‘But that raw sensation that I had as a kid encountering these things, and the energy it brought, has stayed with me. I still draw on that today.’

In art school (first Aarhus University, then Central Saint Martins and the University of Copenhagen), Kudsk Steensen would build virtual worlds, then create paintings of the landscapes within these worlds ‘to make it art’. It was a way to fulfil his passions while conceding to the popular misconception that painting had greater aesthetic merit. He moved away from painting as soon as he graduated and started to build his career around virtual worlds. ‘It’s funny how you have to exit the doctrine of a system you’re brought up in to innovate within it,’ he reflects.

Moving to New York six years ago, the artist found kindred spirits in the growing immersive media sector. One was artist and writer Rindon Johnson, who became the voice of Kudsk Steensen’s Aquaphobia (2017), in which viewers follow a water microbe through a Brooklyn park, while listening to a break-up story between man and the landscape. Another was composer Michael Riesman, music director of the Philip Glass Ensemble, who created algorithmic music for the video and VR piece Re-animated (2018), inspired by a recording of the mating call of a Hawaiian Kaua‘i ‘ō‘ō bird that had been the last of its species. The most important partnership of all has been with sound artist Matt McCorkle, whom Kudsk Steensen met through New Inc, the New Museum’s creative incubator programme. Like Kudsk Steensen, McCorkle has a love of nature and fieldwork, often gathering sounds ‘in extreme isolation to capture our natural world at its purest essence’. The project in Brandenburg’s wetlands is their fourth together.

‘Jakob came over to my studio one night, and I played some whale sounds I recorded for a then-upcoming show at the American Museum of Natural History, “Unseen Oceans”. We realised at that point our work gelled together like magic,’ McCorkle remembers. ‘We have a similar fondness for the minute details in nature, often exploring the tiny worlds that pass us by in our everyday lives. For example, a small mossy patch on a decaying log is an entire world in and of itself, if you look and listen close enough. Patience is key to the work we create together. We let nature guide our work and expose to us how she wants to be presented in a particular ecosystem.’

Shortly after meeting, Kudsk Steensen and McCorkle began to work on The Deep Listener (2019), an artwork commissioned by Serpentine Galleries in collaboration with Google Arts & Culture and architect David Adjaye. It involves an app that takes its users on a journey around Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, using augmented reality to present the sights and sounds of five elements of London’s ecosystem – London plane trees, bats, parakeets, azure blue damselflies and reedbeds – and to illuminate the ecological interplay between humans and non-humans. The title refers to the slow and embodied process of attentive listening that is necessary for learning and reflection.

Kay Watson, Serpentine’s interim head of arts technologies, recalls: ‘Jakob’s was one of over 350 ambitious works submitted for the first Serpentine Augmented Architecture commission.

His notion of “slow media”, that technology could be used to foster attention and engagement with the natural world rather than detract from it, resonated with us all.

Kudsk Steensen’s next stomping ground was markedly different from London’s green spaces. Accepting a residency at the Luma Foundation in Arles, he decided to research the wetlands of the Camargue. ‘You have these basic life forces of salt, algae and water. Depending on how dry or wet it is, everything will feel and look completely different,’ he says. He documented this process over a year for a multiplayer VR piece titled Liminal Lands (2021), created with McCorkle and now on view as part of the group show ‘Prélude’ at La Mécanique Générale.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

His residency in Arles coincided with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. ‘I really started thinking about embracing hyperlocal sensitivity, and what it meant to suddenly travel the international art circuit a lot less, and really be present in the landscape,’ he says. ‘It shifted something inside of me, deeply and profoundly. Through this much more extreme engagement with nature, I found out that you have to spend enough time in a place to start seeing it, to realise that it looks and feels different than anything you can imagine.’ There was more work to be done on wetlands still. And so when the Berlin-based art foundation Light Art Space approached him for a new commission, he decided to stick to the topic, and go further.

Light Art Space offered him a major solo exhibition at the Halle am Berghain, one of the German capital’s most celebrated cultural destinations. It’s an extraordinary opportunity that is well aligned with Kudsk Steensen’s ability to reach a wide range of audiences (besides art lovers and gamers, he has a loyal following among the fans of K-pop sensation BTS, who invited him to present a virtual forest ecosystem, Catharsis (2020), as part of global public art project ‘Connect, BTS’). ‘I work with people from different fields. We don’t care about the conventional frameworks, as long as we have a meaningful engagement with people,’ he comments.

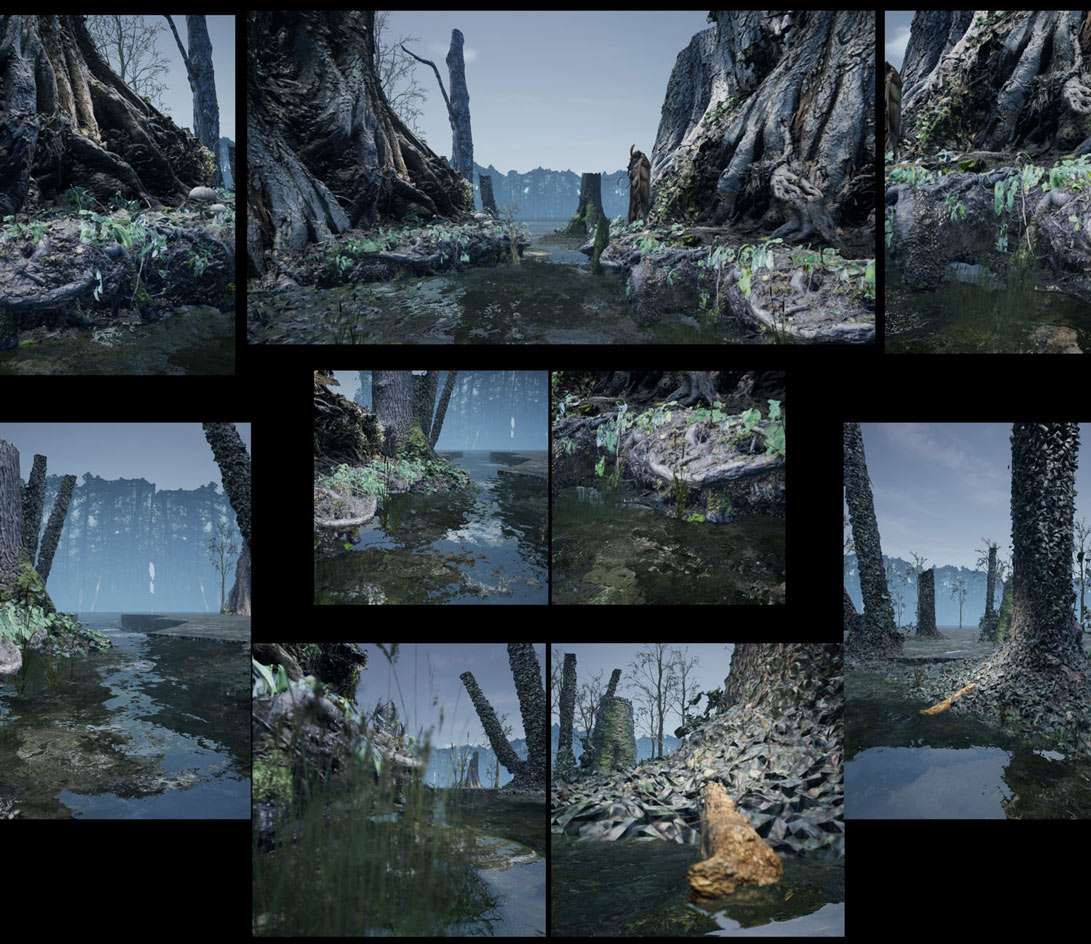

Installation view of the original iteration of Berl-Berl, at Halle am Berghain, Berlin, 10 July–26 September 2021.

The exhibition also comes with a heavy burden of expectation. ‘It’s not the type of show where you just roll in as an art world figure with your artwork. You have to embrace what the building has been as a nightclub, and what it might become, without alienating its history and existing community, without appearing to gentrify yet another space in a city that used to have all this energy.’

To live up to its venue, the exhibition, titled Berl-Berl, would have to be epic, collaborative, democratic and one-of-a-kind. Kudsk Steensen’s solution was to create a virtual swamp that would take over all of Berghain, encouraging viewers to contemplate the forgotten complexity and beauty of wetlands. Joining forces with fellow artist Dane Sutherland, Kudsk Steensen began to research historical perspectives on wetlands and swamps. They learned that many major cities in the world are connected to wetlands. Brandenburg, the state that surrounds Berlin, is one big wetland that emerged from a glacial valley 10,000 years ago, and Berlin’s name in fact derives from the old Slavic word ‘Berl’, which means swamp.

Installation view of the original iteration of Berl-Berl, at Halle am Berghain, Berlin, 10 July–26 September 2021.

Wetlands have also been considered sites of imagination, of fertility, of spirituality. In many religions, wetlands connect our world to the world of other animals, and to the heavens.

Kudsk Steensen explains that across Europe and North America, this changed in the 1800s, when wetlands came to be seen as undesirable. People began to remove and pave over them. Today, freshwater wetlands account for only one per cent of our planet’s ecosystems. As the artist laments, ‘they have become lost from the public imagination’, despite their exceptional biodiversity, ability to filter toxins, and the protection they offer against rising sea levels.

His next port of call was Berlin’s Museum of Natural History. Its director, Professor Johannes Vogel, has been on a mission to revolutionise the way data in natural history museums is used. ‘Natural history museums have to inspire and encourage people to see themselves as part of nature,’ says Vogel. ‘It is extremely exciting and inspiring to learn from artists how human emotions can be evoked and how we can engender dialogue. It is fantastic to see how Jakob has a different approach to a museum object than we as natural scientists have – how we can engage through textures, sounds or virtual access.’

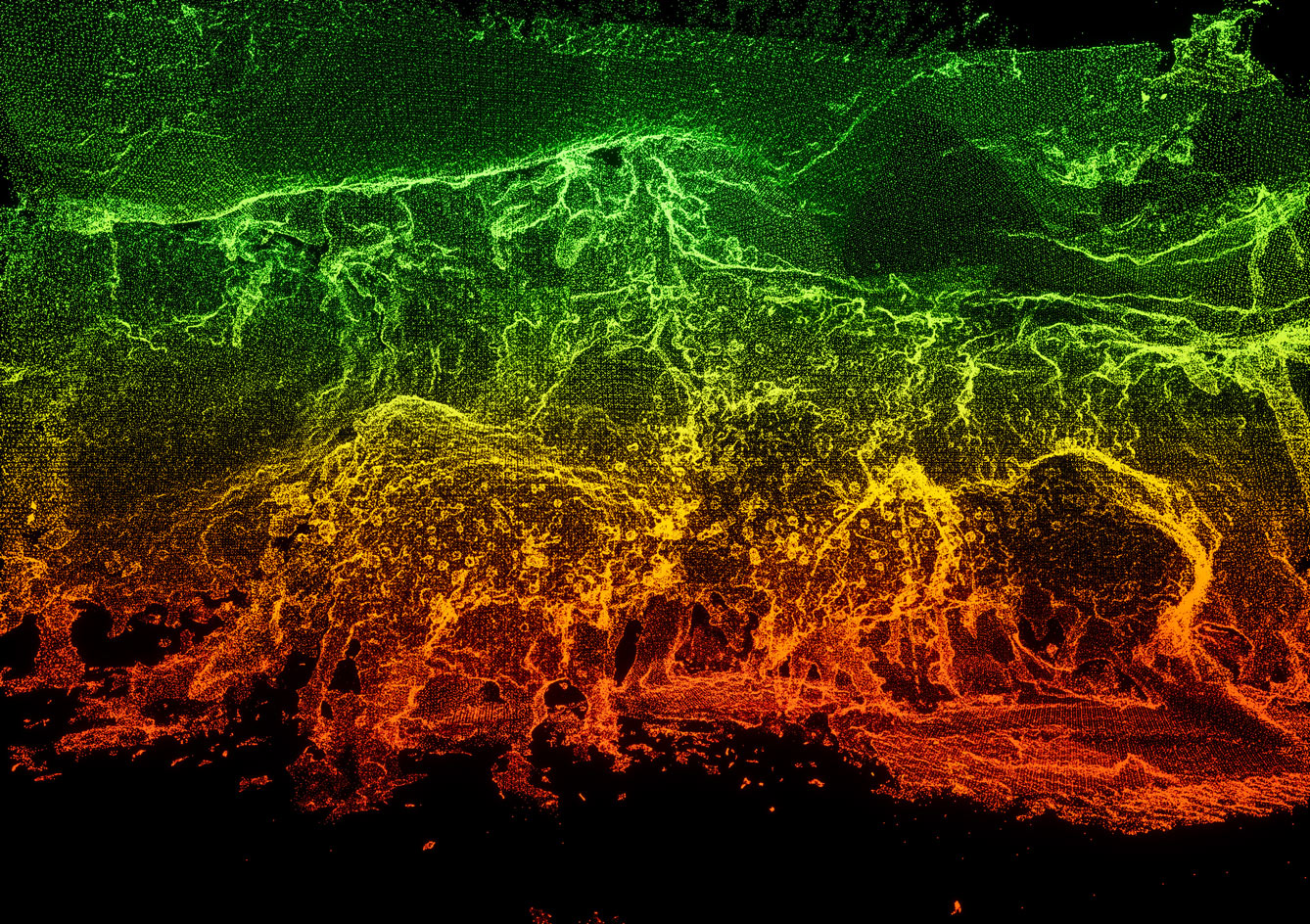

The museum has a vast sound archive, including recordings of frog songs from the wetlands of Brandenburg since the 1960s. Going through these recordings, Kudsk Steensen was struck by how much they have changed. So it wasn’t just that enlightenment ideals banished wetlands from our midst, those that remained were increasingly damaged by human activity, too. He also met with the museum’s scientists. The soil in wetlands, they told him, can include organisms that died 2,000 years ago but have yet to dissolve. ‘So the energy is still in the soil. It’s kind of alive,’ says Kudsk Steensen. ‘Then when you look at past religions and folklore, they also talk about the soil as being alive.

I had the idea that when you work in a wetland, you’re working with parallel realities, multiple worlds coexisting between different species, between different time periods, between science and something spiritual.

Installation view of the original iteration of Berl-Berl, at Halle am Berghain, Berlin, 10 July–26 September 2021.

With this in mind, he set out to explore the Spreewald Biosphere Reserve, bringing along McCorkle, producer Andrea Familiari, and field biologists from the museum, whom he values not only for scientific knowledge but also for their emotional connection to their subject. ‘I like to bring experts from different fields with me into the landscape. I give a sense of direction, in the theme of the work and the story, but they’re very much themselves, responding to the landscape and being part of the artwork’s creation.’

There are precise steps to complete in the wetlands, such as using macro photogrammetry to 3D-scan flora and soil in ultra-detail. But Kudsk Steensen has allowed for spontaneity, too. ‘Once we’ve spent weeks sailing in canoes, looking around, we can experience and see things we didn’t imagine. We procure new sensations, spaces, visuals and sounds, bounce that back on our original material, and then go to the studio to put all this together in a single, holistic experience.’

Back in Berlin, where Kudsk Steensen has been doing a residency at Callie’s, a non-profit experimental institution, he assembles his raw material into a virtual wetland that is at once hyper-realistic and surreal. Gentle waters lap against cragged boulders and gnarly trees cloaked in emerald green moss, pristine reeds stand tall in turbid pools, luminescent fungi emerge from fertile soil. It looks at once like a sophisticated video game and a Romantic landscape painting that has come to life (later, when asked to name his artistic heroes, Kudsk Steensen mentions both the iconic Japanese game developer Hideo Kojima and the 19th-century German painter Caspar David Friedrich).

A post shared by Jakob Kudsk Steensen (@jakob_kudsk_steensen)

A photo posted by on

McCorkle drew from the Museum of Natural History’s archival material and his own recordings to create orchestra-like compositions, which feature three species prominently: the common frog, the European fire-bellied toad and the cuckoo. Further birds, bats and an aquatic insect called the water boatman play supporting roles. ‘The main soundscape consists of many different compositions, each with their own emotional toll, lightness and influence,’ says McCorkle.

Humans are notably absent from this virtual landscape, and indeed from Kudsk Steensen’s earlier works. ‘We have so much art already that focuses on the human. I want to direct the eyes at the world beyond our human domain, to bring a sense of mystery, imagination and fascination,’ says the artist. Still, in a departure from previous practice, Kudsk Steensen has invited the Venezuelan musician Arca, whose ‘morphing sensibilities’ he has long admired, to contribute to the project. At Kudsk Steensen's invitation, Arca improvises raw vocals that are then layered into McCorkle's soundscape, along with spoken examples of various names by which Berlin has been called over the centuries, further rooting the virtual experience in its physical location.

A post shared by Matt McCorkle (@equalsonics)

A photo posted by on

The seven metaphorical verses of Berl-Berl – the human world, fungi world, root world, trees, frozen world, skies and water – come together in real time rather than following a predetermined sequence. Nine LED screens broadcasting live video have been installed in the cavernous Halle am Berghain, once the machine hall of a district heating plant. ‘The landscape exists on a server, which tells us what time of the day it is, what things look and feel like. And it sends that signal to all the individual computers, who render their own local version of that environment with those shared variables, which shows on the screens. So you get this constellation of screens throughout the space, offering little windows into the landscape, and something shared among them,’ says Kudsk Steensen.

Creative technologist Lugh O’Neill developed the sound technology to transform McCorkle’s compositions into a generative soundscape, parsing the information from the server into the sound experience. ‘This information dictates when and which parts of my composition play, how long they play, how much they connect to Jakob’s visuals and the overall emotional timbre they emit,’ says McCorkle.

The world is alive in a sense that you’ll never experience the same visuals and sounds in the same way, shape and form.

Ambitious in scale and astonishing in detail, the resulting artwork is a marvel of VR technology. Kudsk Steensen is already thinking about Berl-Berl’s life beyond Berghain: to extend the reach of the installation, he has created a web portal so viewers can tune in from anywhere in the world. He also points out that because the artwork is virtual, it can infinitely morph and change, adapting to future contexts in which it will be shown.

Installation view of the original iteration of Berl-Berl, at Halle am Berghain, Berlin, 10 July–26 September 2021.

‘Berl-Berl contributes to the development of new aesthetics and formats, presenting a radical new visual language,’ says Bettina Kames, the director of Light Art Space. ‘The heart of the world Jakob is bringing to life lives on a gaming engine, taking this technology to a new extreme. Very few people have worked with this complex mix of technical elements and scale in the art world. But importantly, Berl-Berl is not about highlighting technology, but using it to offer a certain kind of experience to discuss wider issues. It will allow new perspectives on our environment and create a space for connecting to an endangered ecosystem.’

For Kudsk Steensen, the ultimate goal is to expand the possibilities of virtual reality technology and digital art. ‘I don’t think of myself explicitly as an activist artist, though I work with themes like extinction and the preservation of wetlands.

For me, the real sense of activism is using technology for something very emotional, intuitive, almost ritual or spiritual; showing that technology is something you can use to imagine, express and feel, and be with the environment.

Kudsk Steensen concludes: ‘This is not a narrative we often hear, and I think that’s the strength of it. That’s what I’m here for: I want more poetry in technology.’

A post shared by Jakob Kudsk Steensen (@jakob_kudsk_steensen)

A photo posted by on

INFORMATION

Jakob Kudsk Steensen, Berl-Berl, 4 June–23 October 2022, ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, Denmark, aros.dk

ADDRESS

Aros Allé 2

Aarhus 8000

Denmark

TF Chan is a former editor of Wallpaper* (2020-23), where he was responsible for the monthly print magazine, planning, commissioning, editing and writing long-lead content across all pillars. He also played a leading role in multi-channel editorial franchises, such as Wallpaper’s annual Design Awards, Guest Editor takeovers and Next Generation series. He aims to create world-class, visually-driven content while championing diversity, international representation and social impact. TF joined Wallpaper* as an intern in January 2013, and served as its commissioning editor from 2017-20, winning a 30 under 30 New Talent Award from the Professional Publishers’ Association. Born and raised in Hong Kong, he holds an undergraduate degree in history from Princeton University.