Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary art

As Jack Whitten exhibition ‘Speedchaser’ opens at Hauser & Wirth, London, and before a major retrospective at MoMA opens next year, we explore the American artist's impact

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

In the early 1970s, US artist Jack Whitten underwent a dramatic change in his practice. Moving away from the gestural approach of Abstract Expressionism, Whitten instead developed his own highly innovative techniques that partially concealed traces of his hand behind tools and automated processes. Three events are held responsible: a mental ‘restructuring’, somewhere between breakdown and breakthrough following years of overwork, a desire to distance himself from the influence of the New York School and an encounter with jazz royalty, John Coltrane.

Of these, the last provides the most compelling explanation for what followed. Something about the physicality with which Coltrane played, the way he utilised body and breath, but also his ability to create rich texture by stacking or stretching notes, sparked the idea for Whitten of surfaces that were simultaneously flat planes, but, like Coltrane’s sliding notes, contained infinite depth.

Jack Whitten, Greek Alphabet Series, 1976

Using improvised tools of his own design: combs, saws, rubber squeegees and other modified serrated instruments, Whitten began raking his personal blend of acrylic into parallel grooves that ran across the entire canvas, at times coalescing with the imprinted forms of objects he’d placed beneath. The resulting abstract compositions, whose dense, tactile surfaces result not only from scraping tools but ice picks, polishers, drills and screwdrivers, fused Whitten’s physical dexterity as a skilled craftsman with an obsession to invent and discover, something that would ultimately define the rest of his career.

For the remainder of the 1970s, Whitten relentlessly pushed the limits of his tools and techniques across different mediums, from acrylic paint to paper, printer toner to timber. Several key examples from this innovative decade feature in a new exhibition at Hauser & Wirth, London. Reflecting the haptic, corporeal energy that fuelled Whitten’s approach during this period, ‘Speedchaser’ includes his renowned Greek Alphabet series, deconstructed Xerox scans, and totemic wooden sculptures that he carved on the Greek island of Crete.

Following the opening of ‘Speedchaser’, and with one eye on Whitten’s major retrospective at MoMA next year, we consulted US artist Glenn Ligon and Chisenhale director Zoé Whitley on the artist’s inimitable legacy and unique approach to materiality.

Behind Jack Whitten’s legacy

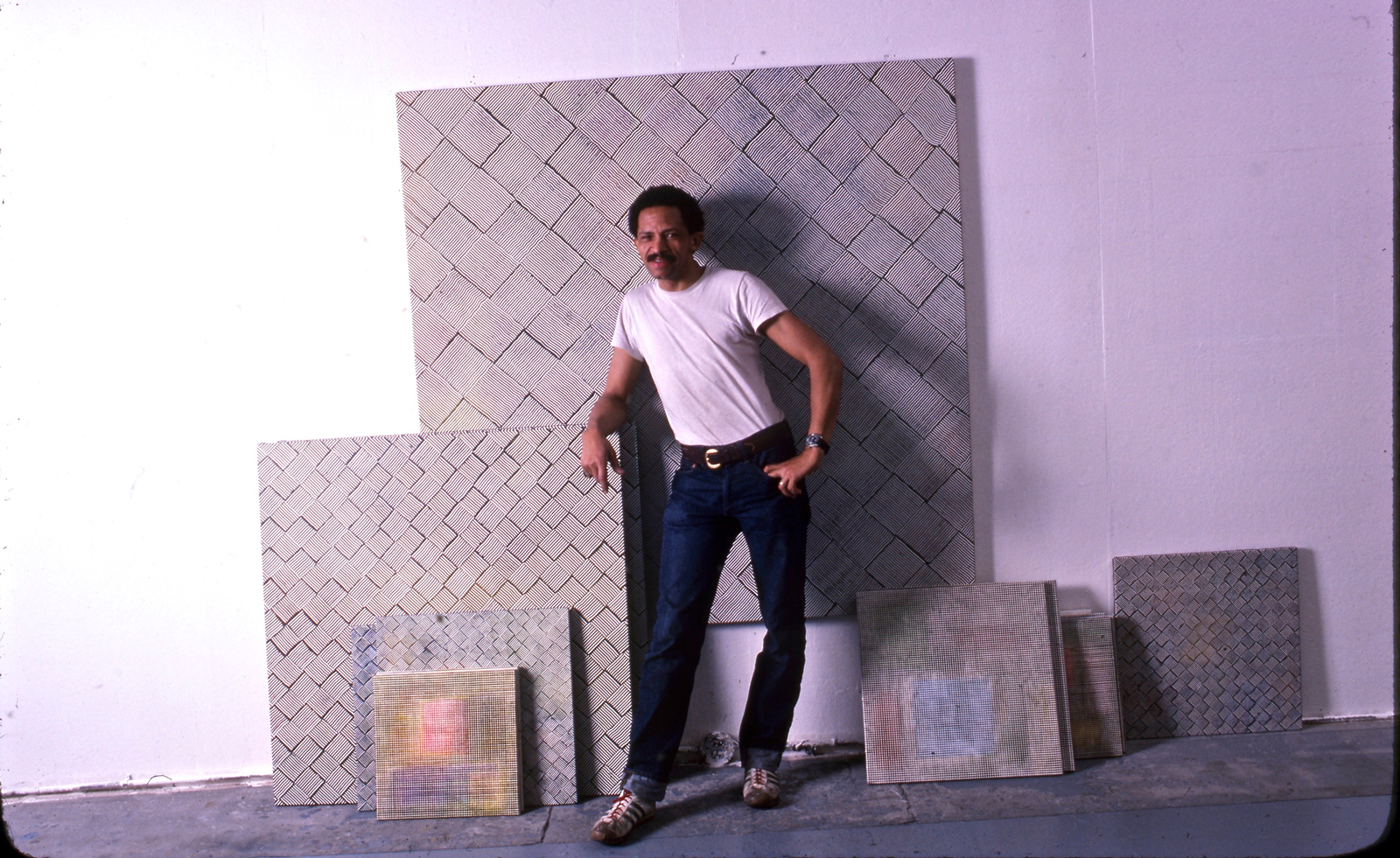

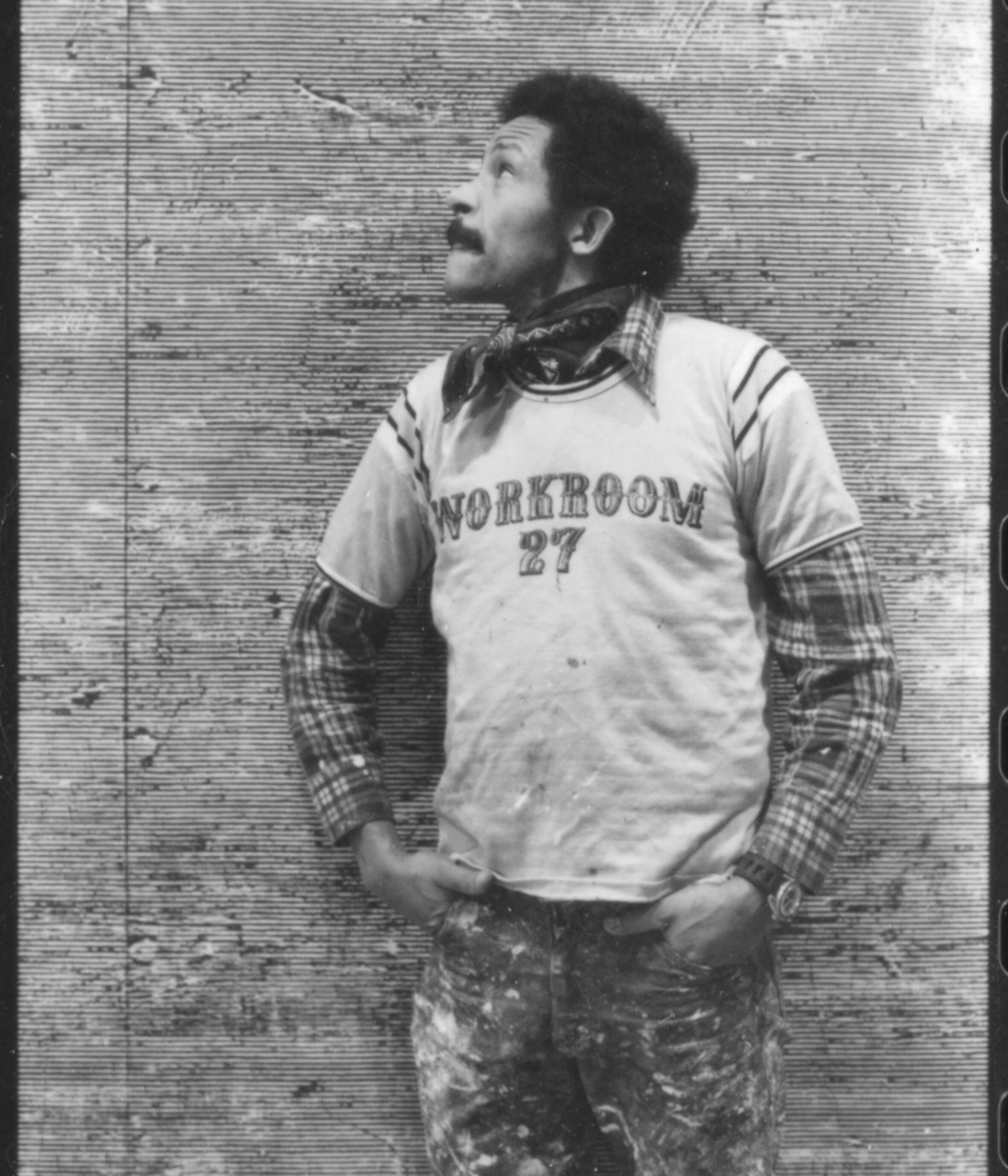

Jack Whitten in his 40 Crosby Street Studio in New York in 1979

Wallpaper*: How have Whitten's innovative techniques or exploration of materials influenced your own artistic process, especially in terms of texture and form?

Glenn Ligon: I discovered Whitten’s work late in my career. He was the mentor I could have had if his work had been taught in the art schools I attended in the late 1970s and early 1980s. I had to find him on my own, and when I found his work, it took me a while to figure out that he had something profound to say about abstraction and figuration and the porous line between the two.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

W*: Whitten often engaged with the social and political realities of African American life through abstraction. How has his ability to convey complex cultural narratives inspired your approach to incorporating text, history, and identity in your work?

GL: In 1988 Whitten made Black Monolith I, A Tribute To James Baldwin. I saw that painting for the first time in 2017 in a show at Hauser & Wirth, London. The painting is abstract but Whitten is very clear that the essence of James Baldwin – a writer he knew personally and who was a great influence on him – was ‘in the painting’. While I have long included Baldwin’s words in my paintings, Whitten showed me how to engage the writer’s ideas on a more abstract level.

W*: Whitten pushed the boundaries of abstraction, sometimes incorporating figuration or personal symbols into his work. Has his blending of abstraction and representation influenced the way you juxtapose text, language, and imagery in your art?

GL: For me, text paintings I make are figurative paintings and abstract paintings at the same time. The blurring of those categories comes from thinking about Whitten.

W*: Can you tell me about one of your favourite works by Whitten from the 1970s and what it means to you?

GL: There was an amazing show of Whitten’s Greek Alphabet paintings at Dia:Beacon in 2022. Those paintings were, for me, about Whitten setting up procedures and guidelines to make paintings and then disrupting the very rules he had set up for himself. Artists are always trying to balance control and abandon in the studio. Whitten was a master of that.

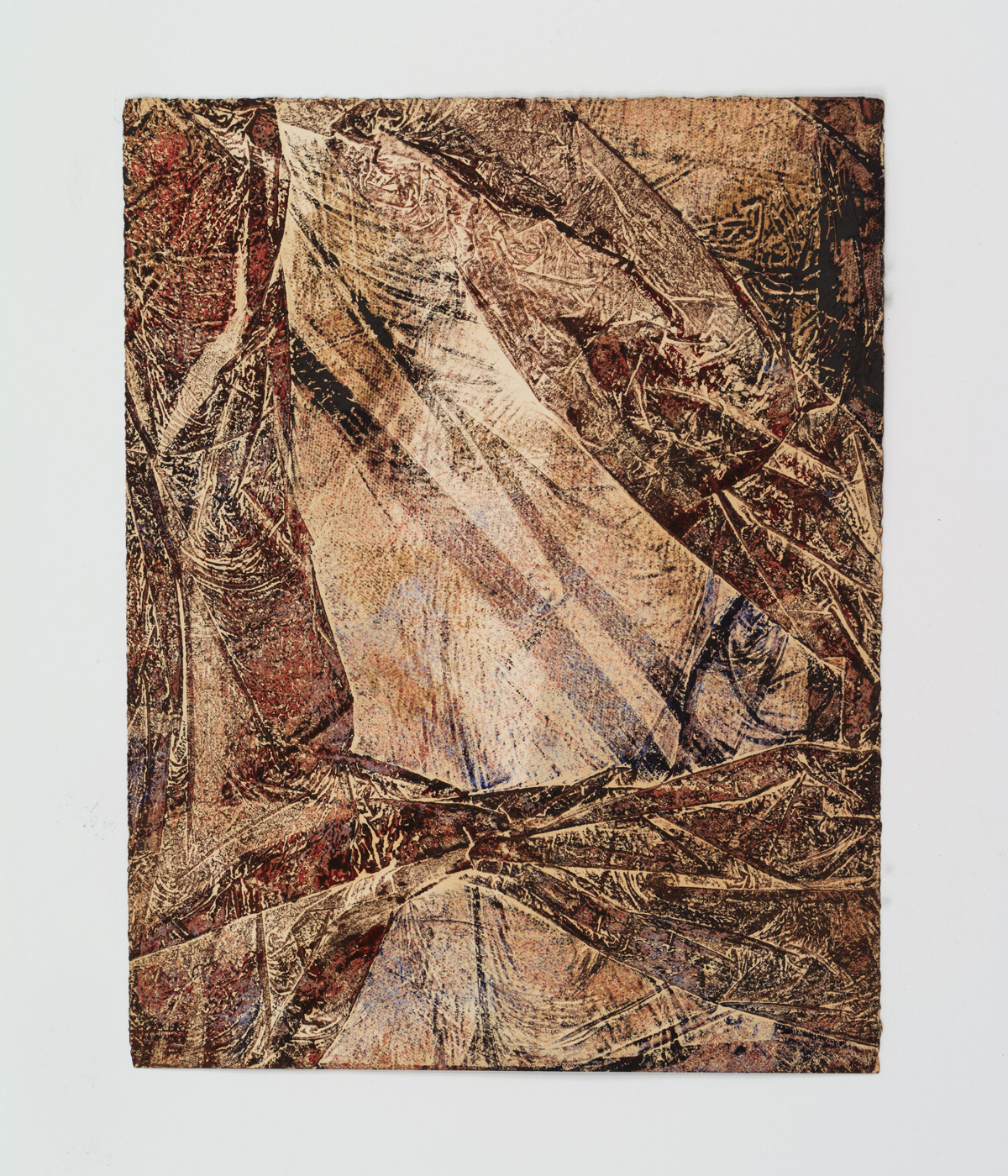

Jack Whitten, The Heart of Humanity, 1972-1973

W*: This exhibition focuses on Whitten's transition from gestural brushstrokes to innovative, automated processes during the 1970s. You've referred to Whitten as 'a voracious thinker and maker'. What about his wide range of interests inspired this technical and conceptual switch in practice?

Zoe Whitley: This is a big question and an important one. For me, Jack Whitten is a quintessential abstractionist. While he was initially influenced by figurative expressionistic gestures made by artists like Arshile Gorky when he first came from Southern University to New York City, he wanted to face the conceptual challenge of moving with, and through, the density of paint head-on. He took the whole of his life – the good, the bad, the joyous and the vulnerable – and distilled it through gesture into wondrous things, sometimes relatively inscrutable, always technically innovative. Jack knew how to transform theory into practice. He asked himself: how might he make a single line into a painting?

He restructured his studio so that the canvas would be on the floor and he built a structure called the ‘Developer’ that allowed him to rake acrylic paint over a huge area in one rapid, smooth movement. That's how works like The Speedchaser were made.

He read a great deal and certain texts he name-checked as having a transformational effect on his practice. The French philosopher Gaston Bachelard wrote the Poetics of Space in 1958. Bachelard was a game-changer because his ideas centred on lived experience in architectural spaces; the conceptual was married to the feeling. That was one turning point. George Kubler’s The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things was published in 1962. Jack noted this was another formative text because it shifted his understanding of time and his relationship to memory, which became more freed from notions of linear time. Series like Pressed Space start to make sense in relation to Jack's bookshelf!

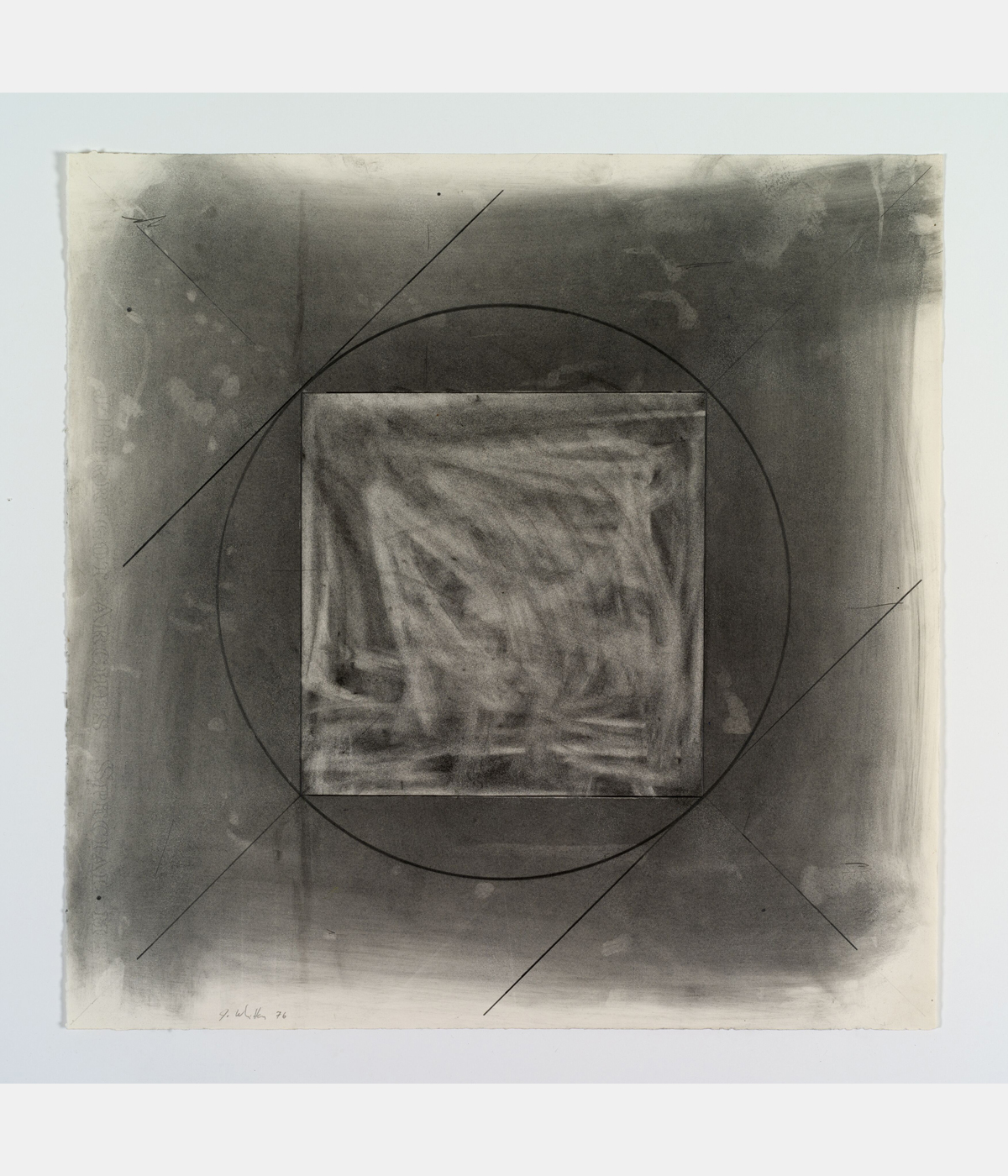

Jack Whitten, Xeroxed!, III, 1975.

W*: Whitten stretched the materiality of painting in a way few others considered before him, but the ineffable and spiritual were also an important element to his practice. Can you tell me about the importance of the metaphysical in his work?

ZW: Descriptors like ‘transcendent’ we tend to reserve for religious paintings from the Renaissance, but we should be applying them to works like Whitten's too. This is yet another example of how he channelled his beliefs into actions, his faith into practice. He literally fought the good fight against evil as a civil rights freedom fighter. Non-violent action and passive resistance takes guts. Turning the other cheek is one thing to read about in the Bible and another when you are being pushed in the face and doused with human waste. So art for Whitten was in some ways a refuge, not only a private one, but an expansive cosmology that he allowed us all to share in.

W*: How do you see the relationship between Whitten's early exploration of sculpture in Crete during the 1970s and his evolving approach to painting during the same decade?

ZW: With the benefit of hindsight, it seems clear he approached sculpting like a painter and then, in turn, began painting like a sculptor, embracing the new dimensionality on a flat surface. He found ways to adapt the painting palette so that he was using sculptors' tools on canvas. Conversely, his sculptural compositions always factor in a playful interplay of light and density, as if manipulating something more malleable than the solid forms we are actually perceiving.

W*: Can you tell me about your favourite work of Whitten's from the 1970s?

ZW: It's all about first love for me: Asa's Palace. The painting vibrates and swallows you up in pink and purple, then you come up for air in short bursts of yellow-grey-green. It's the painting that helped me understand what Jack meant when he talked about resisting narrative, not ascribing meaning to colours and just letting the truth come through. He really trusted each colour to hold its own.

W*: Next year will see the opening of Whitten's first retrospective at MoMA. How would you describe Whitten's contribution to American contemporary art and successive generations of young Black artists?

ZW: Jack Whitten was generous with his time and his knowledge and skills. He was never boastful but he understood completely his position as both a teacher, imparting wisdom and encouragement to younger artists, and his parallel role as a lifelong student learning from writers, fellow artists and technology. I wouldn't restrict his influence to any one race, generation or group of creative practitioners. He shifted things for all of us: artists, curators, and thinkers alike.

Jack Whitten, 'Speedchaser', is at Hauser & Wirth, London until 14 December 2025

Jack Whitten, Pressed Space.

Jack Whitten in his 40 Crosby Street Studio in New York in 1979

Finn Blythe is a London-based journalist and filmmaker