Erik Kessels’ found photographs hint of jealousy, love and intrigue

The artist fills in the blanks of his newfound photography book, laden with violently defaced portraits discovered in a dusty Budapest archive

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Erik Kessels delights in the art of ‘bad’ photography. It’s in life’s little mistakes, he argues, that authenticity, humour, and intention are most at home. A thumb smudged in front of a lens, an album of hilariously over-exposed family pets, cellotape marks touching the sky at the edge of an image. Kessels – an artist, art director, designer, and head of Amsterdam-based advertising agency KesselsKramer – has long celebrated this found, amateur photography. He finds it online, through friends and contacts, and (less so nowadays) at flea markets, and publishes series by unassuming photographers, often completely unaware that they’ve created little moments of visual genius, in his vernacular photobook series In Almost Every Picture, now in its 15th iteration.

But this kind of found photography is dying out. ‘These days, we’re all editors. We take photos to share, not to keep,’ Kessels explains. ‘And everyone seems to have some version of Photoshop. I watched a 70-year old woman on a flight the other day delete around 500 images she'd taken of her grandchildren, saving only the two most perfect ones.’

But ‘perfect’ doesn't always mean ‘good’. We save the clean, crisp, professional-looking images; all smiling eyes and sound composition. The rest – filled with lens flare, stolen glances, reality – vanish forever into the digital dustbin. Once upon a time they would have at least graced the cutting-room floor; ready to be salvaged by the likes of Kessels, from flea markets and collectors' archives. ‘Bad’ photography is becoming more precious than ever.

This isn’t to say Kessels is anti-Instagram – quite the opposite. ‘The platform is fantastic – it’s free, and so much more democratic,' he explains. ‘We’re exposed to more photography before lunch than people in the 18th century would see in their lifetime.'

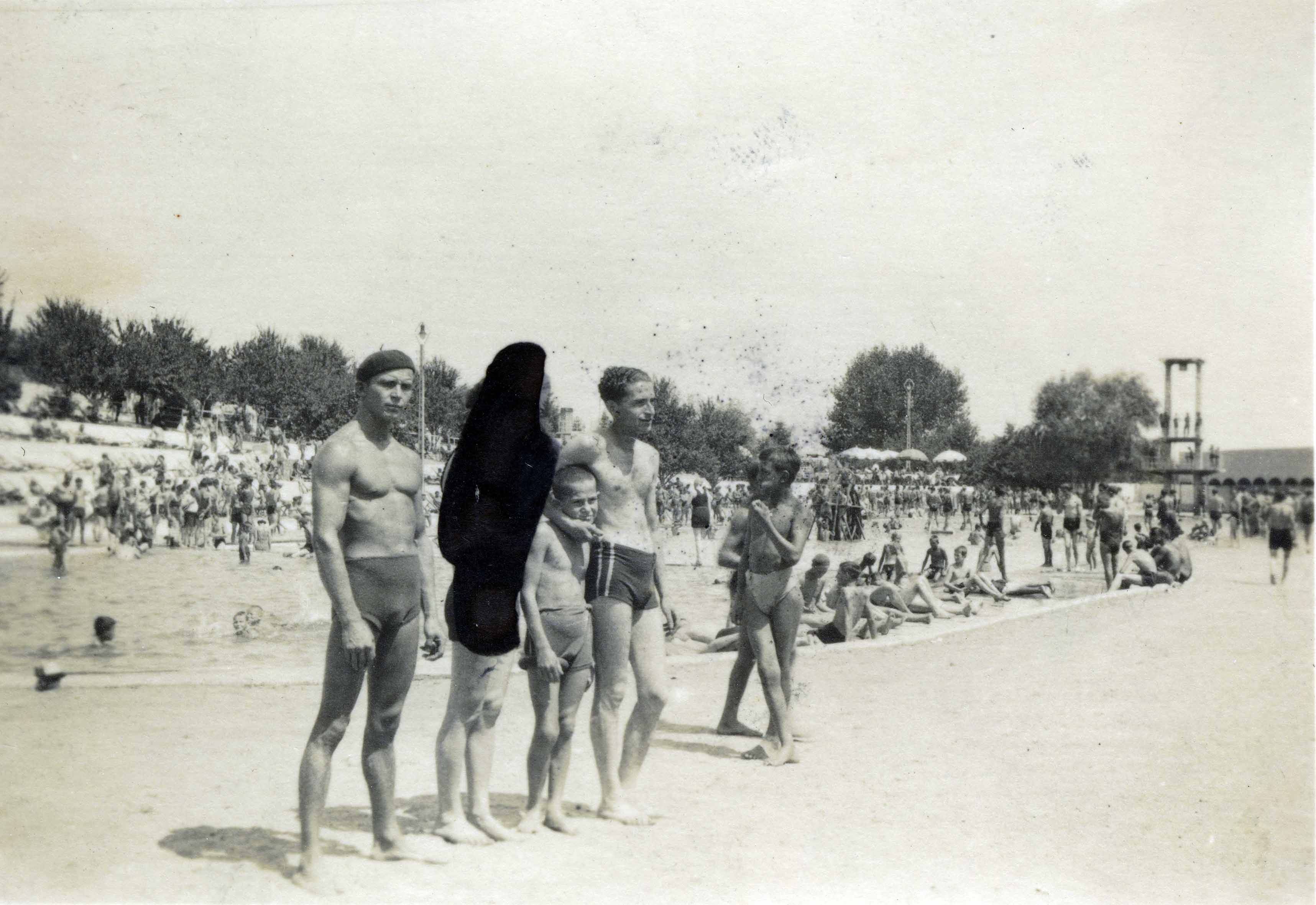

But there’s still something special about the physical experience of thumbing through a photo album. For the latest iteration of In Almost Every Picture, he visited a collector friend in Budapest, who gave him permission to use 52 fascinating portraits. In each, an unknown man stands with his arm round a woman, who has been scrubbed out retrospectively in black ink. Some unknown assailant has attacked these images with enthusiasm, in a kind of physical Photoshopping that Kessels calls ‘an analogue way of “unliking” someone’.

This is not the work of a fighter’s wife, but a fighter herself. Fighting to keep her man, even from the ghosts of his past

The rather straight-laced looking man in the photographs is not the protagonist – nor is the mysterious woman behind all that black ink. Instead, its the censor we're interested in. Who are they? What motivated them to deface 52 photographs like this? Surely it would have been easier just to throw them all away? Kessels leaves it up to us to fill in the blanks, but of course, he has his own rather fanciful theory. ‘From careful brushes – taking care to not besmirch the man – to jealous scribbles, this is an artist with stylistic range,’ he says. ‘The brush strokes in these pictures are more concerned with the censor’s own feelings rather than enhancing the overall aesthetic. This is not the work of a fighter’s wife, but a fighter herself. Fighting to keep her man, even from the ghosts of his past.’

Perhaps so. Perhaps it’s an angry child in a fit of rage, perhaps a disapproving parent. The beauty of the series is in the not-knowing. In an age of captions, hashtags, geotags, and metadata, let’s leave this one mysteriously unexplained. Kessels tempts: ‘Come up with your own narrative.'

INFORMATION

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Elly Parsons is the Digital Editor of Wallpaper*, where she oversees Wallpaper.com and its social platforms. She has been with the brand since 2015 in various roles, spending time as digital writer – specialising in art, technology and contemporary culture – and as deputy digital editor. She was shortlisted for a PPA Award in 2017, has written extensively for many publications, and has contributed to three books. She is a guest lecturer in digital journalism at Goldsmiths University, London, where she also holds a masters degree in creative writing. Now, her main areas of expertise include content strategy, audience engagement, and social media.