Aldo Frattini Bivouac is a mountain shelter, but not as you know it

A new mountain shelter on the northern Italian pre-Alp region of Val Seriana, Aldo Frattini Bivouac is an experimental and aesthetically rich, compact piece of architecture

A mountain shelter with a footprint smaller than 4m x 2m, the Aldo Frattini Bivouac is a contender for the smallest building ever featured in the Wallpaper* architecture section. The structure’s seemingly precarious position – perched atop the pre-Alps Alta Via delle Orobie Bergamasche in Val Seriana, surrounded by snow-topped, jagged peaks and sublime valley drops – only serves to make the red speck in the landscape somehow feel even smaller and more lightweight.

Its appearance, however, belies a remarkable amount of design intelligence and collaborative exploration. The bivouac’s function is at the root of its being – permanently open, the small space offers shelter and emergency provision for climbers and alpine walkers, should the weather turn or the final stretch to the nearest habitable spot be impossible. That said, architecture borne of necessity and clarity of function does not always lead to creative or aesthetically rich design, though here a genuinely collaborative and exploratory approach has resulted in a neat, compact, and layered building.

Enter the Aldo Frattini Bivouac, a mountain shelter with a difference

The project grew from GAMeC, the Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Bergamo in the Lombardy city, 40km southwest and a couple of thousand metres below the bivouac. Lorenzo Giusti, GAMeC’s director, is himself a keen mountain hiker as well as curator of the two-year Orobie Biennial, for which the cultural institution has programmed a series of projects inviting artists to ‘Think Like a Mountain’.

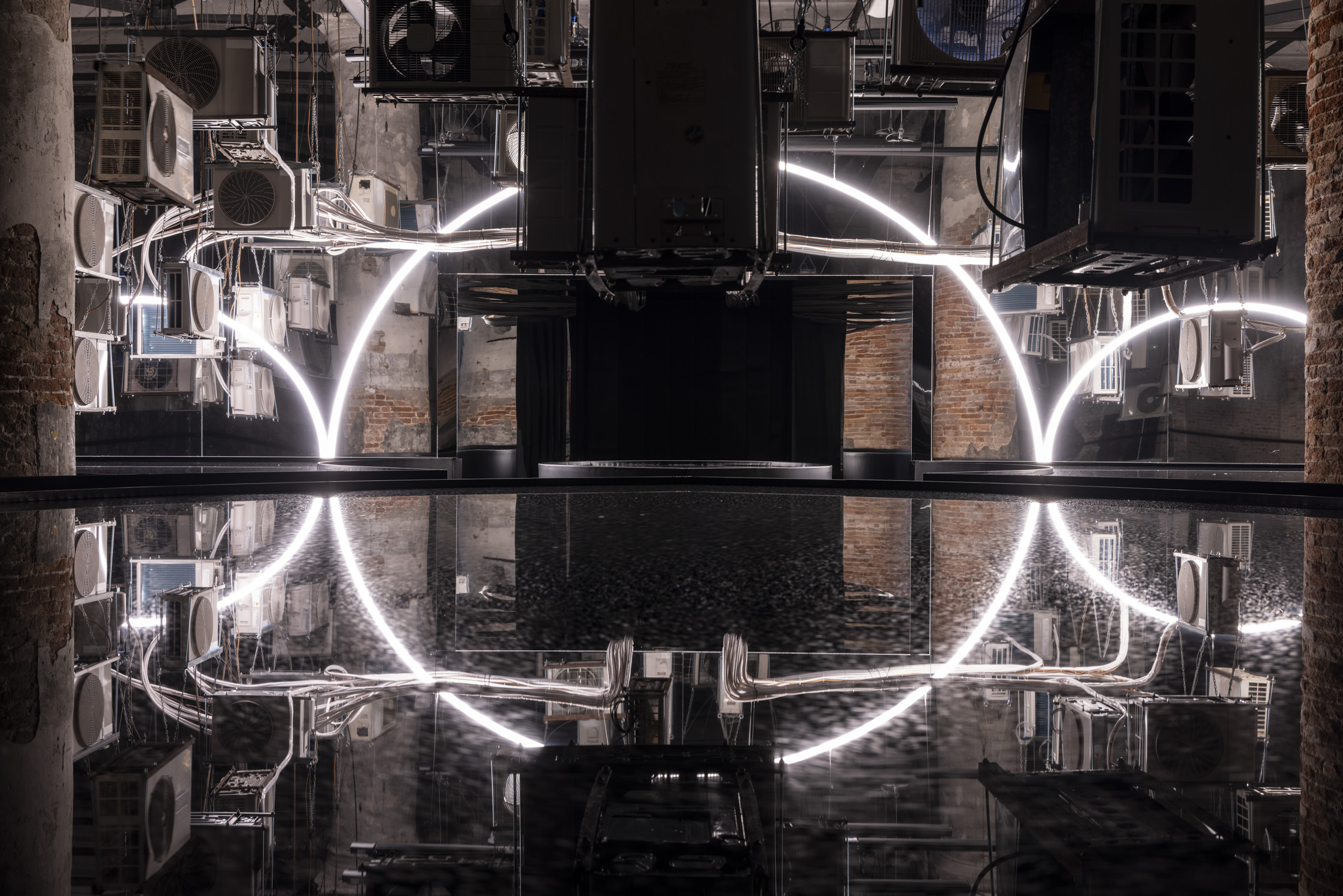

The bivouac is a structure primarily designed to offer critical and emergency shelter, but is also a remote outpost of GAMeC itself, not for exhibitions but to gather data, images, and environmental monitoring towards creating a connection of understanding between the urban context of Bergamo and the mountainous environment to the north.

The first collaboration was between Giusti and the local section of the national Alpine Club. There was already an existing shelter at the location, but as a decaying asbestos shed, it was not fit for purpose. Giusti approached Ex., a research and design studio led by Andrea Cassi and Michele Versaci, who met while working at Carlo Ratti Associati, in part as they had constructed two previous alpine shelters alongside the more commonplace interiors and exhibition designs of a developing architectural practice.

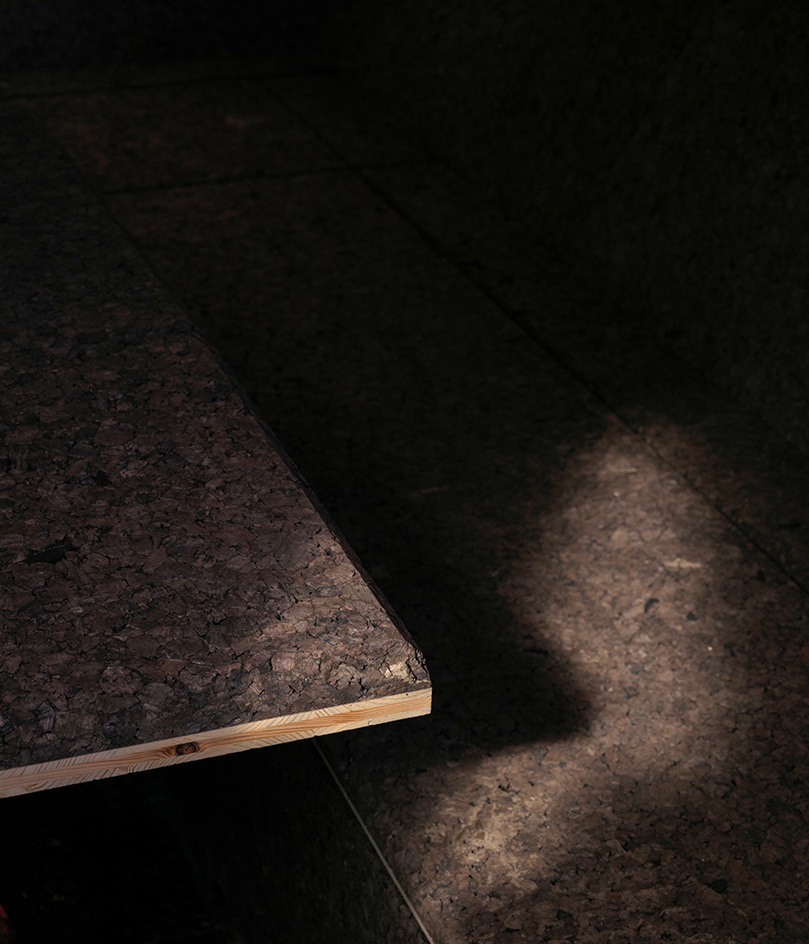

One of those previous shelters was designed not only spatially, but sensorially, with its pine finish offering a comforting scent. There is the same intent with this new bivouac, the entire cocooning space formed of cork, chosen not only for a soft haptic function, but also its sound-insulating qualities. The space may rarely ever have to, but it is designed to accommodate nine alpinists in a carefully choreographed arrangement of beds unfolding from the shell, should – in the worst scenario – that number be needed. So, while it will mainly be unused or accommodate the occasional climber, it needs to function for such an unexpected, emergency crowd.

If the place is hard to get to for climbers, it is harder still for construction workers. Prefabricated in three parts and the whole thing weighing around 2000kg, it was dropped into place by a helicopter over an afternoon before being carefully conjoined as snowstorms grew. The site does not allow for much flexibility, so clarity and exactitude of both design and construction were critical. As soon as the components of the new shelter had been dropped into place, the former, asbestos-riddled and clunky shelter was lifted from its perch and taken to a place of safe deconstruction.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

In such a remote, resolute, and raw space as the Alps, there is the risk that any human-made construct looks artificial, enforced, or violent. 'There can be a colonisation of the mountain with culture,' says Andrea Cassi, aware of the impact of both artwashing and architectural intent into even the most remote, non-urban spaces. 'We tried the opposite, to learn from the culture of the Alps – with a respect towards the environment.' Externally, the shelter is the opposite of an iconic imposition; its final skin is formed of fabric, rippling in the wind and softening the permanence of the intervention.

Its external form evokes an early alpine tent, the shimmering lightweight fabric made in Turin by Ferrino, a company long-associated with mountaineers, though usually through clothing and equipment rather than architectural skin. The joy of such a tensile material – other than the bright red acting as a flashlight to those most in need in an emergency, as well as evoking the charismatic colour of its predecessor – is that it is easily replenishable. Should a wind whip too strongly, or should a crampon catch and tear, it is formed of parts that can be easily replaced without damage to deeper function or fabric. Should material technology evolve, or GAMeC want to collaborate with an alpine artist, there is potential for change.

2025 is the centenary of Italy’s first bivouac on the side of Mont Blanc. From the start, the intent was for a light touch, offering immediate and important rescue while impacting in the slightest way, considering today’s technology. At first, such structures were corrugated metal boxes, the design progressing through the materials of the times, including the asbestos shed that was the precursor to this new Aldo Frattini Bivouac.

What has changed is our legibility of landscape and understanding of its precarity, and our impact upon it. As technologies and shared concerns around Anthropocenic issues progress, so too have our architectural responses. Ex.’s response, in collaboration with many – including an art institution and alpine club, engineers and material fabricators – only speaks to the kind of shared and considered response to the places we love that is needed.

While the Aldo Frattini Bivouac looks small in its site and precarious in surrounding conditions, it is robust and resolute. Almost as a counter to such delicate intervention, and in a far more urban context, GAMeC is also currently engaged in a far larger construction project, that of a new art centre, due to open in 2026. It will become a significant addition to Bergamo, but through the bivouac, we are reminded that the fundamentals of architecture – shelter, security, and aesthetic – are less the domain of big-budget and iconic projects, but fundamental to the most precarious of locations and constrained sites. Arguably, there, even more so.

Will Jennings is a writer, educator and artist based in London and is a regular contributor to Wallpaper*. Will is interested in how arts and architectures intersect and is editor of online arts and architecture writing platform recessed.space and director of the charity Hypha Studios, as well as a member of the Association of International Art Critics.

-

Explore the work of Jean Prouvé, a rebel advocating architecture for the people

Explore the work of Jean Prouvé, a rebel advocating architecture for the peopleFrench architect Jean Prouvé was an important modernist proponent for prefabrication; we deep dive into his remarkable, innovative designs through our ultimate guide to his work

-

'I wanted to create an object that invited you to interact': Tej Chauhan on his Rado watch design

'I wanted to create an object that invited you to interact': Tej Chauhan on his Rado watch designDiastar Original which Rado first released in 1962 has become synonymous with elegant comfort and effortless display of taste. Tej Chauhan reconsiders its signature silhouette and texture on the intersection of innovation and heritage

-

High in the Giant Mountains, this new chalet by edit! architects is perfect for snowy sojourns

High in the Giant Mountains, this new chalet by edit! architects is perfect for snowy sojournsIn the Czech Republic, Na Kukačkách is an elegant upgrade of the region's traditional chalet typology

-

Modernist Palazzo Mondadori’s workspace gets a playful Carlo Ratti refresh

Modernist Palazzo Mondadori’s workspace gets a playful Carlo Ratti refreshArchitect Carlo Ratti reimagines the offices in Palazzo Mondadori, the seminal work by Brazilian master Oscar Niemeyer in Milan

-

Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu to curate the 2027 Venice Architecture Biennale

Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu to curate the 2027 Venice Architecture BiennaleChinese architects Wang Shu and Lu Wenyu have been revealed as the curators of the 2027 Venice Architecture Biennale

-

At the Holcim Foundation Forum and its Grand Prizes, sustainability is both urgent and hopeful

At the Holcim Foundation Forum and its Grand Prizes, sustainability is both urgent and hopefulThe Holcim Foundation Forum just took place in Venice, culminating in the announcement of the organisation's Grand Prizes, the projects especially honoured among 20 previously announced winning designs

-

Carlo Ratti reflects on his bold Venice Architecture Biennale as it closes this weekend

Carlo Ratti reflects on his bold Venice Architecture Biennale as it closes this weekendThe Venice Architecture Biennale opens with excitement and fanfare every two years; as the 2025 edition draws to a close, we take stock with its curator Carlo Ratti and ask him, what next?

-

Step inside Casa Moncler, the brand’s sustainable and highly creative Milanese HQ

Step inside Casa Moncler, the brand’s sustainable and highly creative Milanese HQCasa Moncler opens its doors in a masterfully reimagined Milanese industrial site, blending modern minimalism and heritage, courtesy of ACPV Architects Antonio Citterio Patricia Viel

-

The 2026 Winter Olympics Village is complete. Take a look inside

The 2026 Winter Olympics Village is complete. Take a look insideAhead of the 2026 Winter Olympics, taking place in Milan in February, the new Olympic Village Plaza is set to be a bustling community hub, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

-

Anish Kapoor designs Naples station as a reflection of ‘what it really means to go underground’

Anish Kapoor designs Naples station as a reflection of ‘what it really means to go underground’A new Naples station by artist Anish Kapoor blends art and architecture, while creating an important piece of infrastructure for the southern Italian city

-

‘Landscape architecture is the queen of science’: Emanuele Coccia in conversation with Bas Smets

‘Landscape architecture is the queen of science’: Emanuele Coccia in conversation with Bas SmetsItalian philosopher Emanuele Coccia meets Belgian landscape architect Bas Smets to discuss nature, cities and ‘biospheric thinking’