Amid populist turbulence, Istanbul’s art scene is forging defiantly ahead

The city’s cultural cachet is rising, buoyed by the 16th Istanbul Biennial, Contemporary Istanbul art fair and the unveiling of Arter museum

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Daily (Mon-Sun)

Daily Digest

Sign up for global news and reviews, a Wallpaper* take on architecture, design, art & culture, fashion & beauty, travel, tech, watches & jewellery and more.

Monthly, coming soon

The Rundown

A design-minded take on the world of style from Wallpaper* fashion features editor Jack Moss, from global runway shows to insider news and emerging trends.

Monthly, coming soon

The Design File

A closer look at the people and places shaping design, from inspiring interiors to exceptional products, in an expert edit by Wallpaper* global design director Hugo Macdonald.

Istanbul is perhaps the most fascinating of urban venues in which to gather and discuss art. It’s a true metropolis – the world’s fourth biggest city, home to just over 15 million people. Its streets are a warren-like maze, a cacophony of noise and movement. Up high, in one of the many sky-bars, it’s impossible to see the city’s edges. And it’s easy to marvel at the Bosphorus, a glistening strait teeming with vessels that, from the days of the Silk Road, have joined west and east.

And it’s a place singularly capable of harmonising two identities: one determinedly secular, youthful and outward-reaching, the other deeply conservative, patriarchal and embedded in the mores of the past. Turkey also has one of the oldest and proudest artistic traditions of any culture in the world, yet modern day Turkey is an almost uniquely hostile place for contemporary art. This tragic paradox lies in plain sight on the World Press Freedom Index, where Turkey currently stands at number 157, below failed states like the Democratic Republic of Congo (154) and renowned dictatorships like Russia (149).

Beyond the high-profile arrests of the artist Zehra Doğan and the composer Mehdi Rajabian, as well as the exile of feminist artists Özgül Arslan and Ekin Onat, huge numbers of lesser-known Turkish creative luminaries been arrested and imprisoned or glued-up in legal proceedings. Turkey remains the world’s worst jailer of journalists, with at least 68 in jail in direct relation to their work at the time of the Committee to Protect Journalist’s 2018 prison census.

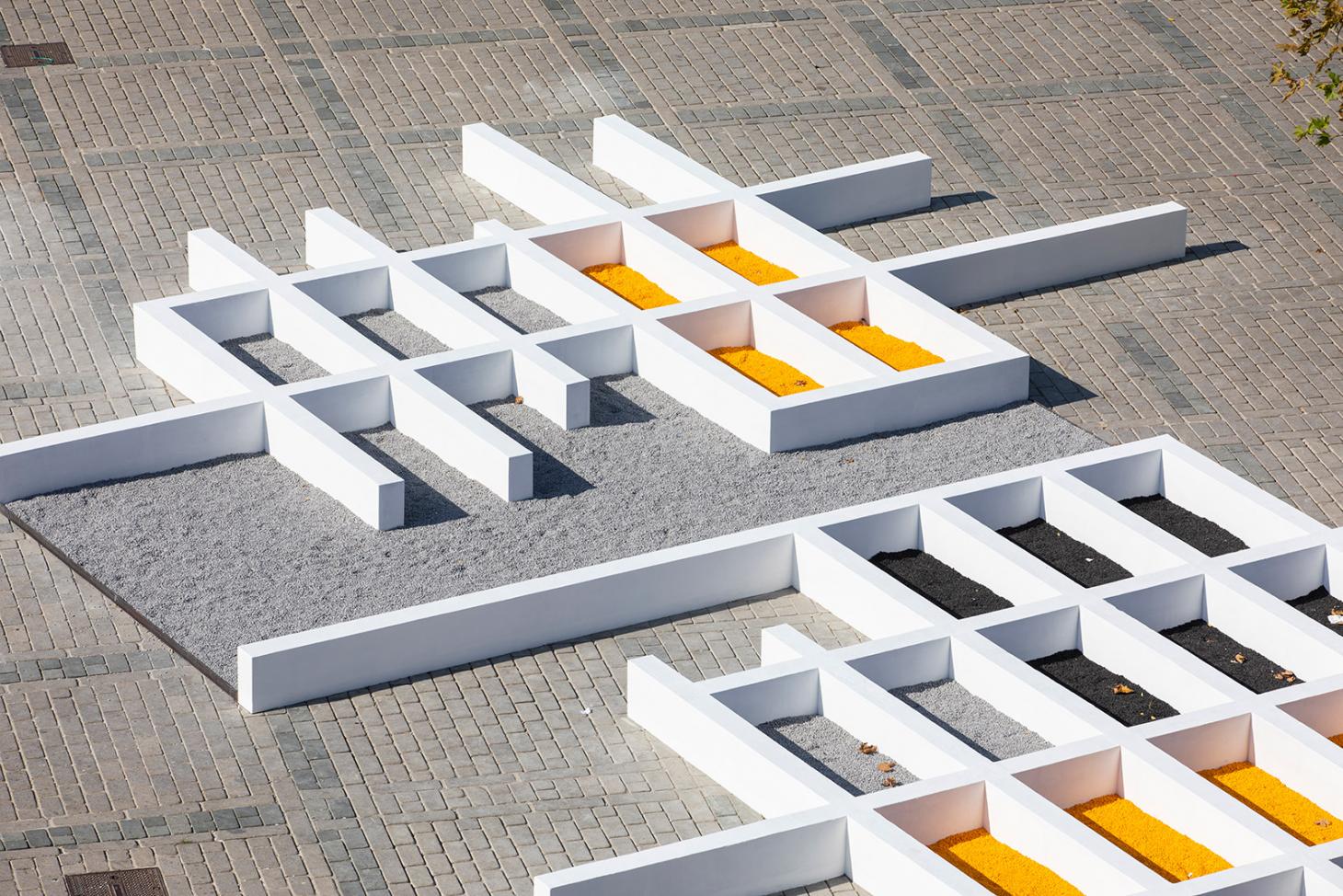

Personal Plots, 2019, by Andrea Zittel. Courtesy of Istanbul Biennial

How to deal with this, and still successfully host a commercial art fair? And what work to show if you are among the country’s latest generation of artists, both native and diaspora? Answers lie at the 16th Istanbul Biennial and Contemporary Istanbul, both of which opened to the public on 14 September. For Nicolas Bourriaud, the French curator of the Istanbul Biennial (running until 10 November), the answer appears to be to focus on the relatively safe and collegiate topic of climate change – ‘the landscape of the Anthropocene’, as Bourriaud terms it.

The title of Bourriaud’s biennial – The Seventh Continent – refers to the mammoth islands of plastic waste that now float in our oceans. They cover, we are told, an area five times larger than the geography of Turkey. Bourriaud has organised the exhibition of works from 56 artists (36 are showing new work), who comment on this phenomena.

The most talked-about highlights include the sculptural work of Polish artist Agnieszka Kurant’s Post-Fordite, which she terms a ‘natural-artificial hybrid formation’. The sculpture, we learn, is moulded from something known as Fordite (also known as Detroit agate) – a paint that, over time, has congealed and solidified into a rock-hard mass on the floor of car factories. Kurant invites us to look at the resulting formation as if it’s an uncut diamond.

Suret, Zuhur, Tezahur, 2019, by Hale Tenger. Courtesy of Istanbul Biennial

Simon Fujiwara’s project began after he discovered and salvaged the semi-ruined figurines of pop icons in the rubbish heap of an amusement park outside of Istanbul. Around the face of each figurine – from Homer Simpson to Mickey Mouse – he built architectural models of cityscapes, thus drawing attention to ‘the ways in which fantasy and escapism have bled into the core structures of our everyday lives, often masking the brutal pragmatism of globalised capitalism’, he says.

Among the prominent Turkish artists at the Biennial, perhaps the stand-out is Amsterdam-based Müge Yilmaz, whose work Eleven Suns can be described ‘as a future archaeology incorporating leftovers of our times’. Yilmaz’s installation resembles the discovery of a sacred shrine in a hidden cave, where we find her mesmerising drawings of hybrid plant-human-animals.

Uptown is Contemporary Istanbul, which took place at the Istanbul Convention & Exhibition Centre (ICEC) in the affluent Sisli neighbourhood. The fair is – at least outwardly – a more commercial presentation of art, one more focused on emergent Turkish artists and less curated around a unifying theme. Much of the work here is highly conceptual in form; perhaps because, to put it bluntly, the government finds it harder to censor abstracted work.

RELATED STORY

Yet Ali Güreli, the founder and chairman of the fair and a significant patron of contemporary art in Istanbul and Turkey, is adamant that the fair does not, and would never allow, the government to censor any work shown at the fair. ‘I cannot say that we feel any pressure from the government,’ Güreli told journalists at the fair’s opening press conference. ‘We never felt it before. But of course we have been living in a different environment in Turkey in the last 15 years, governed by a conservative party. As the art fair, we are a bit more conscious about these precious issues. But I cannot talk about pressure or any censorship.’

Be that as it may, Contemporary Istanbul art fair deserves credit. For, amid the populist turbulence of Istanbul’s recent history, it has remained steady, providing an outlet for Turkish artists and gallerists to exhibit to an international audience. It has taken place every year since 2006, and, now in its 14th edition, brings to Istanbul 73 galleries from 22 countries, with the works of 510 artists on show. As Güreli rightfully points out, much more is to come. The fair has laid the groundwork for Arter, a new five-floor museum dedicated to contemporary art, which this recently opened its doors in the city, while nine more dedicated art galleries and museums are poised to launch in the near future.

There’s no doubt that certain artists here have to practice a form of self-censorship; to do so is to safeguard one’s freedom and self-preservation. Yet some artists on show are clearly finding ways to push the envelope; to say things without explicitly stating it. Take for example Whip of Justice by Turkish artist İz Öztat, who is represented by Istanbul-based gallery Pi Artworks. The sculpture is erected from the metal barriers used by police during the violent Gezi Park demonstrations of 2013, which rocked the city after the Turkish government attempted to ban all public protests.

Stop This Craziness, 2018, by Vav Hakobyan, oil on canvas.

Meanwhile, the Turkish gallery Galeri 77 exhibited a series of works by Armenian artists like Vav Hakobyan, who, with his work Stop This Craziness, appears to be referencing Picasso’s Guernica or Goya’s ghosts with nightmarish, semi-opaque scenes – yet the human faces have been replaced with cartoon characters.

At local gallery Art On Istanbul, the influential Istanbul collective who go by the name Oddviz, displayed a mesmerising video work of a street being denied all its civilising features, the vibrant colours of life stripped away so that only the cold grey of concrete is left. An adjoining large-scale photographic print showed traditional Turkish ceramics, exquisite in their artistry and craftsmanship, smashed into a Klimt-esque mosiac of fragments and shards.

Significantly, the fair included the work of Turkish curator Esra Özkan, who has curated Plugin, a strand of exhibitions focusing on new media and digital arts within the conventional format of an international art fair. This feels especially relevant to Istanbul, at a time when the older generation wield the levers of power, it’s in the digital and online space where virulent resistance movements can be found. This is perhaps best summed up by, the night before my arrival in the city, the sudden release on Youtube of an openly anti-authority hip-hop tune titled Susamam, which translates as ‘cannot stay silent’, and garnered more than 22 million listens in the space of a week.

Some of the stronger criticisms of power came from Turkish artists who no longer have to live under the government, like the New York-based Sarp Kerem Yavuz, who debuted new works at Hüsrev Kethüda Hamamı in Ortaköy, a historic hammam in the heart of Istanbul, considered the famed Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan’s final masterpiece. Yavuz’s exhibition – titled ‘I think the Sultan knows about us’ – ‘uses narrative as a form of resistance’, he says. The artist has channelled the pixelated visual aesthetics that millennial generations will recognise from 1990s Atari games to dress neon skeletons in traditional Ottoman iconography. Yavuz says of the work: ‘The sense of humour I am determined to instil in the visual depictions of this universe is the most unyielding form of resistance in the face of oppression, of fear.’

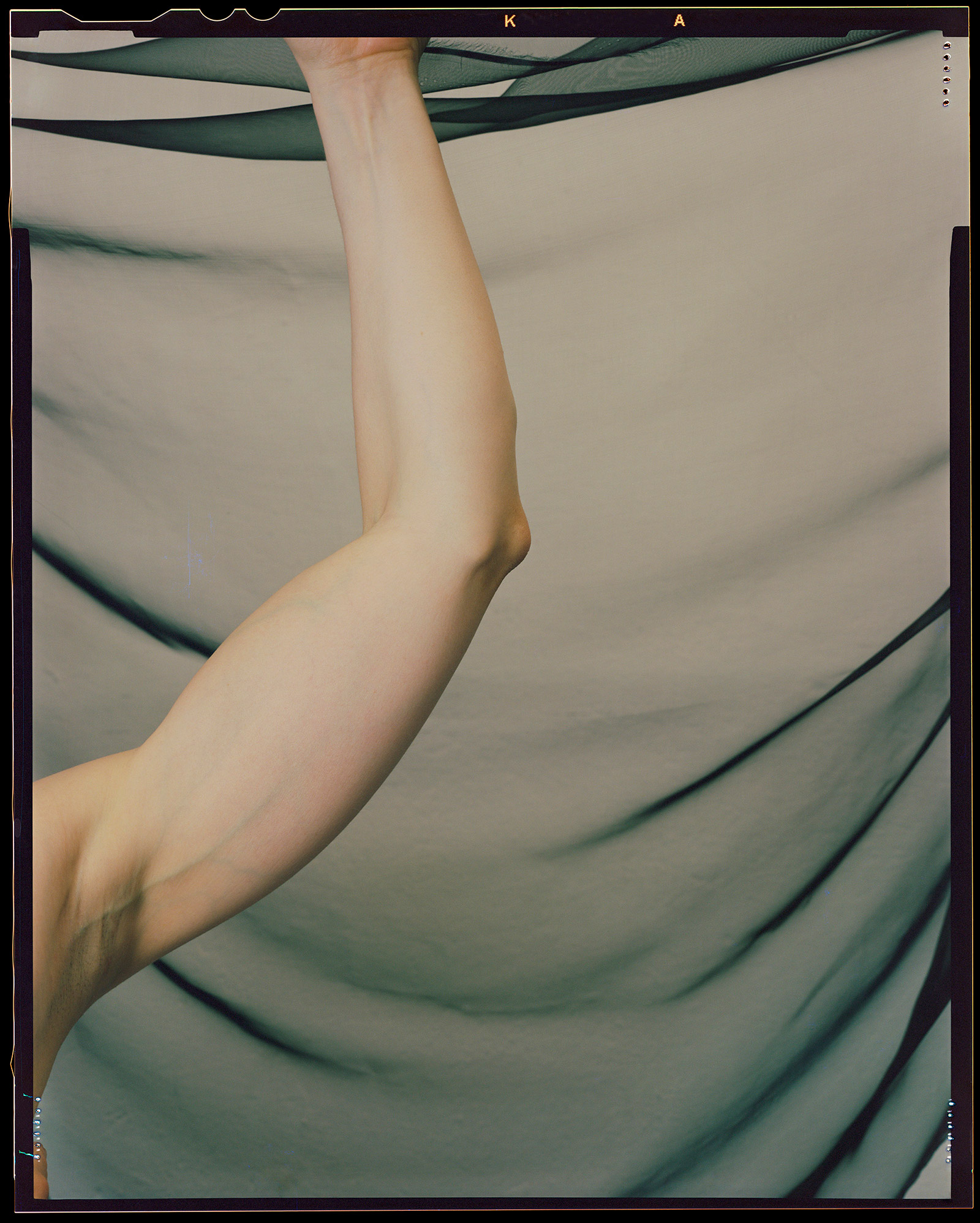

Lesley (after Beaton), 2018, by Ketuta Alexi-Meskhshvili, archival pigment print.

Untitled, 2019, by Deniz Orkuş, mixed media on Plexiglass.

Bust of a Woman (Night for Day), 2018, by Nilüfer Yıldırım, mixed media on paper.

Temblores, 2019, by Juan Genoyes, acrylic on canvas on board.

INFORMATION

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

16th Istanbul Biennial, 14 September – 10 November, various locations; Contemporary Istanbul 2019, 12 – 15 September. bienal.iksv.org; contemporaryistanbul.com

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.